Today's profile of Ramp marks the launch of our new story format, Extendable Articles: It has a built-in chatbot that lets you interrogate not just the story itself, but all the source material behind it—interviews, videos, articles, and other research—that Evan Armstrong used to inform his perspective, and form your own. Read more about why we built the format from Dan Shipper, and let us know what you think of the idea (and the story!) and how it's working for you. (Extendable Articles are currently only available online, so click over to our website to try it out.)—Kate Lee

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

It is hard to make $7.6 billion divine, but Eric Glyman is working on it. Ramp, the finance software company he co-founded in 2019, has raised $1.9 billion in total financing, a ridiculously large sum. To earn this war chest, Ramp became one of the fastest growing startups ever, hitting $100 million in annualized revenue in less than three years.

The company did not accomplish this by spiking the water cooler with Adderall or inventing some sci-fi technology. Instead, Glyman did something different: He started a religion around saving.

Ramp offers a suite of financial software—distributing credit cards to employees, paying bills, and managing expense approvals—for companies, all focused on helping them spend less time and money by automating a lot of the work that is usually done manually. For example, rather than users having to submit expense reports via email at the end of each month, Ramp lets them text the receipt as soon as the purchase occurs. The product suite is full of little automations like this—useful, quick actions that add up to saving customers money.

Automatically turn 1 piece of content into 10—in your voice

You’re probably creating more than ever before—writing essays, recording podcasts, promoting your work on social media. We want to make it easier for you to move fast. Use Spiral, our tool to automate 80 percent of the repeat work that comes after creating—social media posts, YouTube descriptions, newsletter blurbs, and more.

However, it’s the kind of company that is clearly bigger than the sum of its parts. During my research for this piece, I heard investors praise Ramp’s culture, competitors begrudgingly express admiration for its growth, analysts eulogize those same competitors, and compliment after compliment about seemingly every aspect of the business. Shoot, the most common word people used to describe Glyman was “nice.” How often do founders earn that moniker?

As part of my process, the company gave me unprecedented levels of access to Glyman and other members of the leadership team. Still, I found myself disappointed.

Part of me wanted them to have some secret fire stolen from business strategy Olympus. Instead, I discovered that Ramp is winning by making hundreds of small and correct choices. Glyman is laser-focused, as he told me, on being “1 percent better” every day, versus 10 times better periodically. Ramp does the things you are supposed to do as a startup, and it does them well. There is no magic—just hard work and smart decisions.

Glyman, a Las Vegas native who met his cofounder Karim Atiyeh when they were undergraduates at Harvard, has a history of obsession with cost savings. In 2014, the pair started Paribus, a fintech company that helped consumers get rebates when an item they’d recently purchased decreased in price. They sold it to Capital One in 2016.

Still, the seeds of a gospel around savings had been planted. As Glyman and Atityeh looked around, they noticed a central tension with most fintech services. In the first pitch document they sent to venture capitalists, they highlighted a “fundamental misalignment” between traditional financial services companies and their customers: Because fintech companies make their money by collecting a percentage of every transaction a customer made, they would design their software to encourage spending, even though what their customers really wanted was to save money. They wanted their New York–based firm to become a “technology-driven financial services company” that would use software to decrease their users' spend—for example, by flagging when a company had multiple subscriptions to the same software, or benchmarking bills so they could see if their vendors were overcharging them relative to their peers.

The challenge of the 1 percent strategy—of relying on daily, smart choices—is that a CEO cannot make them all themself. They have to trust their organization to make choices for them. You can think of it as the anti-Steve Jobs approach: You have to preach the Good Word and let your followers do the rest.

Glyman’s credo is simple: “Save time and money.” Every decision, from what product to build to how to monetize, is a reflection of this mission.

The magical thing about religion is that adversity makes you stronger, not weaker. A normal company wouldn’t choose to compete with competitors who have raised $1 billion-plus (Brex) or legacy brands with incredibly strong network effects (American Express). But the Ramp team did not worry that they were starting behind. They knew the path. Who cared what everyone else was doing?

In his 2014 book Zero to One, Peter Thiel sang the praises of the mission-driven firm, identifying a higher sense of purpose as one of the key differences between a regular company and a startup. As a result, for years, the canonical advice in Silicon Valley has been to “hire missionaries, not mercenaries.” For what it’s worth, I’m on the record in this column debunking this idea:

“In startup dogma, you are told to ‘hire missionaries, not mercenaries.’ These mythical employees will put it all on the line. They will sacrifice and devote themselves to whatever cause your business is proclaiming as its divine mandate. Hiring these employees is good advice! As a founder, I would also want employees who believe so passionately in what I’m doing that they would take reduced wages and work longer hours. Perhaps it is my inner Marxist, but I can’t help but view businesses proclaiming to be mission-driven to actually be fueled by ideological exploitation.”

Ramp is worthy of study not because they built a big company, but because they did so with complete harmony between their mission and their actions. Their product strategy, compensation, customer set—all of it is defined around the central goal of saving time and money. And they do it in a way that isn’t exploitative or hokey, but that focuses everyone who works there on what matters.

They are also worthy of study because the business is ripping. Beyond their impressive fundraising, in 2021, just 16 months after their public launch, the company crossed $1 billion in annualized transaction volume on the platform. Three years later, they crossed $35 billion and reached that $7.6 billion valuation. The more than 25,000 finance teams that use them include Barry’s Bootcamp, Stripe, Glossier, and Quora. All of this has been accomplished with only about 900 employees.

You should care about Ramp because its founders took perhaps the most boring thing on God’s green earth—expense management software—and made it both mission-driven and hugely successful. Let me show you how.

How the hell does software work?

Ramp started with corporate credit cards. Shortly after, they bundled them with expense management software focused on tracking how employees used them. The goal was to automate the perennially annoying process of having to submit receipts to your company so that employees could save time, and companies could better understand how they were spending money.

This is not a new problem to solve, but it’s one that has lacked a good solution. Expense management software is notoriously clunky, and the tedious labor of matching charges to expense categories is part of what makes accountants some of the most overworked people on the planet.

To understand what makes Ramp so remarkable, you need to understand that all of B2B software is essentially just a spreadsheet. If enough businesses need a spreadsheet to solve a specific problem—say, for example, tracking credit card spend—then voilà, you have an idea for a company. This is called a point solution, meaning that the software only solves one problem.

Now, imagine that a company creates a point solution that works for an initial handful of customers. To grow, that company can expand either horizontally— i.e., by using the same tool to serve a new set of customers—or vertically, by creating new tools to address other problems that its existing customers are facing. So a start-up that sells software for tipping your barista could expand horizontally by helping other types of retailers implement tipping, or it could expand vertically, by selling other types of coffee shop software. While this may not sound exciting, the available opportunity for software companies making these souped-up “spreadsheets” is hundreds of billions of dollars.

The more horizontal the problem, the larger the volume of customers a software company can serve. Ramp is a very horizontal platform; as Glyman told me, it provides essentially the same service to everyone, from “potato farmers to Stripe.” However, even with a point solution focused on a problem that everyone has, the function of a piece of software can change based on the size of a customer and what that customer does. A local coffee shop looking to offer employee benefits may need a different kind of software than a corporation with millions of employees, like Starbucks.

I recognize this is hand-wavy, but think about how overheated this dynamic has made the software industry. Every person at a business, from human resources to finance, has multiple software companies competing to solve their problems. Enterprise companies expand into mid-market. Related industries try to encroach. It is, frankly, ridiculous. And no single software provider can solve all the needs of an individual worker. In 2024, the average employee uses 11 different applications to do their job.

To win, a company needs to own either a client’s most important data or its most important workflow—or both. Imagine if OpenAI were the only company that made an LLM, and you couldn’t operate your software system without it. Or if Salesforce held all the data about your customers in its software, and it was impossible to port that data out. A monopoly on data and workflow allows for reduced churn, increased pricing power, and easier routes to expand to multiple products. A rough heuristic for this calculation is whether a software system is one that a customer would be unable to operate its business without. Whether the data or the workflow takes precedence is highly context-dependent, but every piece of software you use is trying to nudge you into performing your most important work or store your most important data on its platform (or, again, both).

This is especially challenging for Ramp because every enterprise financial product works in a similar way. A transaction is matched to a receipt. From there, a manager will either approve or reject it. Finally, a finance team will annotate the transaction and route it to the appropriate budgeting and accounting software suites.

Billion-dollar companies have been built on top of essentially every word in those last three sentences. Some companies specialize in sourcing discounts for transactions in specific spend categories, such as Navan (formerly known as Tripactions) in corporate travel. Concur and Expensify do receipt matching. Transaction approval? There’s Onestream, Intuit, Brex, American Express, and on and on and on.

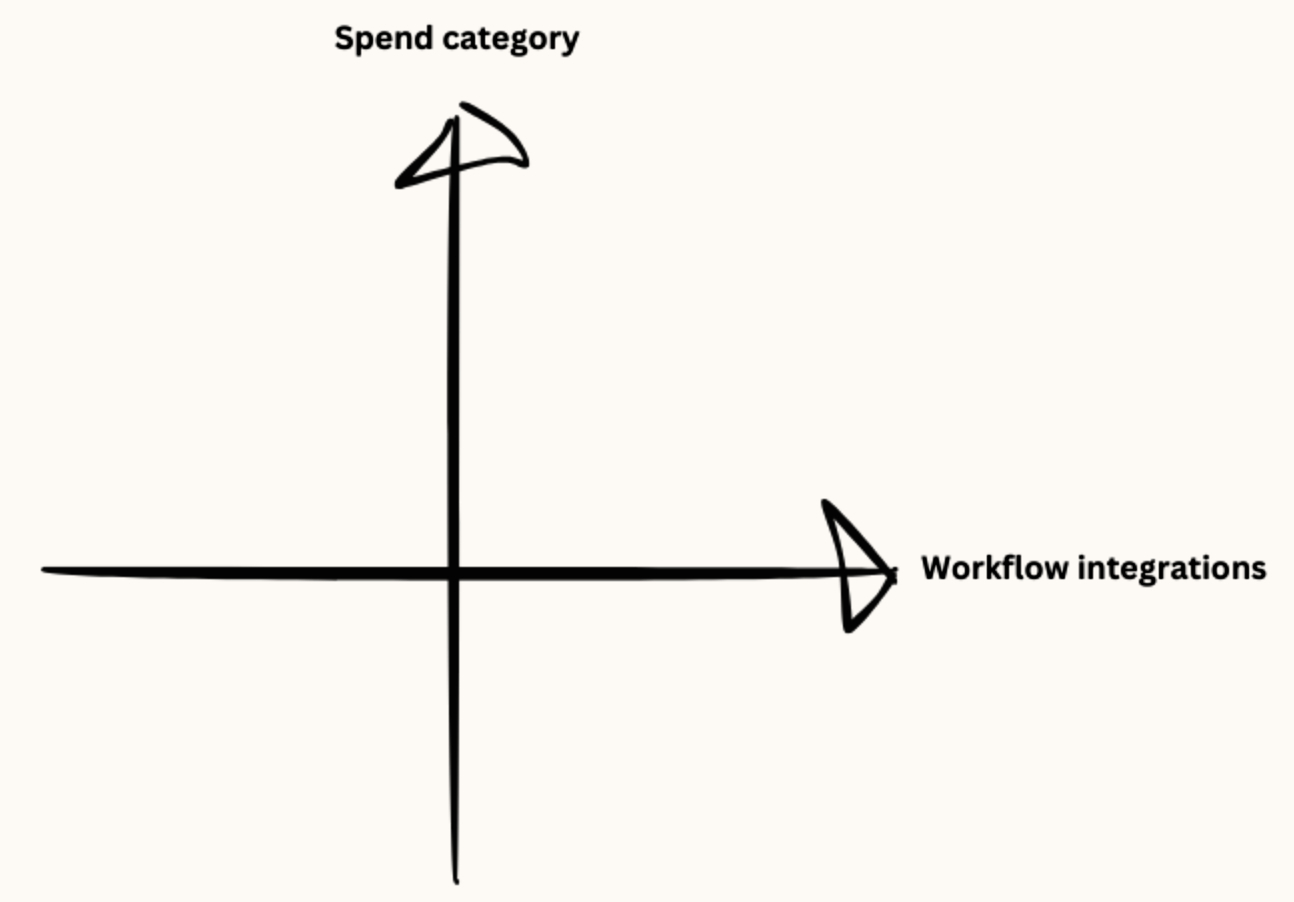

Source: Every illustration.In “finance automation,” the vague category that Ramp is competing in, every company is continually either adding new workflow integrations, like accounting, or new categories of spending, like travel. It’s a roller derby of a market: Everyone is constantly bumping into everybody else in a race to try to overtake the competition.

To make matters even more complicated, every type of financial software does the same core job of transaction recognition, approval routing, and sending data to a company’s general ledger. In the past five years, Ramp has expanded beyond its initial corporate credit card and expense management software to products focused on accounts payable, AI automation, and travel. Each addition to its product suite helps companies save time or money in some way, rather than encourage them to pay more through gamifying spend with points or try to maximize the number of software subscriptions they have.

With all that context, we are back to the original question: Why is Ramp winning?

Tithing

Ramp’s business model is, on first glance, a little simple. They monetized their initial product—corporate cards—using interchange fees: Every time a customer swipes one of their credit cards, Ramp gets a percentage of that transaction ranging from 1-3 percent.

The natural incentive with this business model is to maximize the amount of money that clients spend. Most of Ramp’s competitors do so by offering customers generous rewards or cash-back programs for making purchases. For example, American Express cards come with points that can be used for travel and airport lounge access.

However, Ramp’s mission is to reduce how much clients spend. They figured out that even though a company would spend less on their platform, building software that allowed clients to do vendor consolidation or reduce credit card spend would help them lock in more clients.

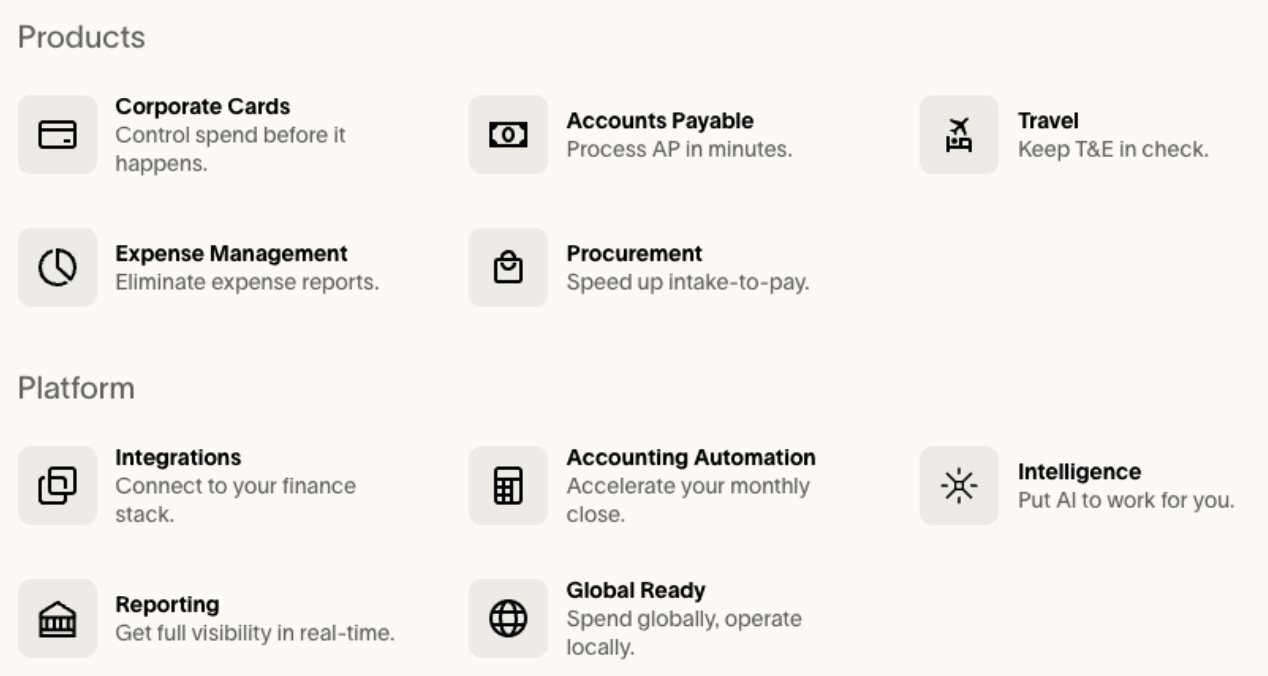

Ramp is incentivized differently than its peers. For every product that it rolls out, from Bill Pay to Travel, the company is willing to monetize less aggressively. That’s because bundling multiple products allows for higher retention, as well as more ways to monetize on the spend flowing through Ramp’s system. For example, check out how their product page expresses each value proposition:

Image source: Author’s screenshot.

Each of Ramp’s products and platforms focuses on speed or money savings. Travel—a product that does approval workflows for employees’ corporate travel—keeps spend “in check” with intuitive workflow software that allows managers to automatically approve or reject travel requests. Expense Management saves time by eliminating expense reports altogether, automating the receipt submission process by having employees send pictures of receipts through text messages.

This is why Ramp says that it offers "finance automation" for companies. It isn’t “billing” with Bill.com or “banking” with JPMorgan. Ramp offers finance automation because it is time- and money-saving software that happens to focus on finance. How each product does that is different, but the mission remains universal. There are many little details sprinkled throughout the platform that make these savings possible. All together, the company estimates the average customer will save 5 percent of their expenses for their company.

My favorite definition of strategy is that it is the art of tradeoffs. Ramp’s religion allows it to make hard tradeoffs with ease. For example, when the company first started, Glyman and Atiyeh turned down multiple millions of dollars after clients asked for a feature that didn’t fit their mission. Here’s how Glyman remembers that moment:

“We had just launched a credit card designed to help people spend less…We were talking with lots of different customers, and some people said, ‘This is really interesting. I would like you to integrate with Concur or Expensify. Every other credit card on the market does this. Ramp hasn't done it yet. Would you go do it?’

It was quite tempting, actually. If you just had a very simple kind of time horizon—if you were trying to make as much money as possible in a day, and your time horizon was really low—you would make that decision, because there were deals that would close… I think we turned away several millions of dollars of business. We were losing by not having that feature.”

Instead of taking the easy money and integrating with third-party expense management software, the company let millions of dollars of revenue sail on by. They knew that in order to own the strategic high ground in the finance software market, they would need to house both the transaction-level data and approval workflows on their own platform. This turned out to be a wise choice, as that initial product bundle became the foundation for everything else they built.

Again, Ramp’s product strategy was aligned with its mission. Owning both the data and the workflows allowed them to save money for their customers and make sure their competitors couldn’t steal market share. This foundational lesson informed each subsequent product.

And the short story is: It worked! As a result, the company is currently “launching [fewer] things to customers,” according to Geoff Charles, the vice president of product at Ramp. “Net-new features are not as important now as they were when we first started off,” he told me, adding that Ramp is still “winning most deals against our competitors.”

All of this success begs the question—how do they keep getting things right? The answer lies in how they've positioned themselves: They aren’t just a service provider; they’re the standard-bearer for a way of doing business.

Converts

Ramp’s competitive landscape is so large and complex that its product bundle acts as a signal for customers. It represents a way of thinking that sets the company apart from its peers: If, as a business, you do not care about credit card points or flashy partnerships and simply want to save time and money, then Ramp is the software for you.

That sounds gimmicky, but as proof of concept, this approach landed Ramp a client in one of the best software companies on the planet: Shopify. A year after Ramp opened their doors for business, a Shopify finance executive saw a funding announcement they published. Then, they just filled out the new client form on Ramp’s website. Yes, you read that correctly—they got a multi-million-dollar deal with an inbound form. (Glyman told me that their system initially auto-rejected the request because it seemed too good to be true.)

A startup barely a year old shouldn’t win the entire business of a Fortune 500. Ramp got the deal because its religion resonates with elite customers. It is looking for converts to its operating model, not just clients. As Glyman sees it, bringing the most innovative companies into the fold and learning from their operating practices helps make Ramp better:

“We want to work with companies that represent where the world is going. There's something about the way these companies operate that will teach you something. If there's a company like Shopify that operates on the forefront for what well-run, efficient, technology-forward companies do—if they want to work with you, but they have specific requirements, we take it very seriously. They are going to pull your product into a direction that actually reveals where more companies are going to be heading. That's been central to our strategy of going up market.”

Ramp approaches other aspects of the business from a mission-driven perspective, too. On top of the usual SEO and email marketing, the company hosts fireside chats with podcasters devoted to the craft of entrepreneurship. They’ll bring the CEO of Airbnb in for an event—not to discuss the value of being a Ramp customer, but to share differentiated hiring strategies.

The company’s employees are missionaries of its gospel. In all my conversations with Ramp staffers (I spoke to six of them), they mentioned speed as a primary operating mandate. The product team’s compensation structure is designed to incentive employees “to do more with less,” Charles told me, which is in contrast to a typical compensation structure that is based on managing more headcount and revenue growth. “It's less about your total breadth and total output. The math [driving compensation] is divided by the number of employees and the costs of your team.”

Despite my usual skepticism of mission-driven companies, I appreciate this approach. The company pays “top of market,” according to Charles, but it does so by making product managers focus on saving both customers money and Ramp’s. Not surprisingly, the company has built a reputation for recruiting incredible talent. While I’m sure their recruiters are wonderful, I got the sense that employees were attracted to the firm on some deeper level.

Mission-driven companies only work if every single aspect of what they do and how they operate—from product to compensation to marketing—align around a central, net-good concept. Consider my opinion revised.

The commandments of Ramp

Compared with the Silicon Valley of old, where people worshiped "disruption" like a golden calf and founders played the role of tech messiahs, Ramp's approach is refreshing. They're simply preaching the good word of efficiency and practicing what they preach.

If Ramp is a religion, we can distill its philosophy down to four commandments:

- Thou shalt align thy business model with thy customers' interests, not lead them into temptation: Ramp makes money when customers use their cards, but unlike their competitors, they don't incentivize wasteful spending. Their goal is to help clients save money, even if it means less revenue for Ramp in the short term—an orientation shared by many of my favorite companies, like Costco.

- Thou shalt sacrifice short-term gains for long-term relationships: The company has shown a willingness to turn down immediate profits, such as when they refused to integrate with popular expense management tools. This allowed them to build a more comprehensive solution that better serves their customers in the long run.

- Blessed are the nice, for they shall inherit the market share: Operating in a distinctive, opinionated, and standup way acts as a signal to customers. You always hear about the importance of “reputation,” and Ramp is a powerful example of that—to the tune of billions of dollars.

- Honor thy incremental improvements, and thy compound growth shall be great: Rather than chasing after flashy 10x gains, Ramp focuses on being "1 percent better" every day. This steady, compounding approach has led to impressive growth, without the volatility that plagues many startups.

Ultimately, Ramp's success suggests that maybe—just maybe—the path to startup glory doesn't have to be paved with the tears of burnt-out employees and disgruntled customers. Maybe you can get there by simply being good at what you do, and not being a jerk about it.

In a world where "disruptive" has become a buzzword devoid of all meaning, that might be the most disruptive idea of all.

Bibliography

The following books, blog posts, and podcasts informed my research for this piece:

- Competing Against Luck by Clayton Christensen

- The Innovator's Dilemma by Clayton Christensen

- High Growth Handbook by Elad Gil

- Blue Ocean Strategy by W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne

- Competitive Strategy by Michael E. Porter

- The Lean Startup by Eric Ries

- "Aggregation Theory," Stratechery by Ben Thompson

- "Visa: The Complete History and Strategy," Acquired

Evan Armstrong is the lead writer for Every, where he writes the Napkin Math column. You can follow him on X at @itsurboyevan and on LinkedIn, and Every on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

We also build AI tools for readers like you. Automate repeat writing with Spiral. Organize files automatically with Sparkle. Write something great with Lex.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Your best article, ever, Evan. Well researched and writing that kept me engaged. It's a refreshing story of a company that does well by following those four commandments that guide their business philosophy. The final line resonates with every business and all I want to work with: Maybe you can get there by simply being good at what you do, and not being a jerk about it.

@[email protected] thanks georgia! appreciate you reading

Super well written. Usually one could take the article and ask ChatGPT for a summary and all that. The amazing expandable article is so cool! Normally one doesn't get access to all the background content. Really enjoyed that. Now, what if I could even add some more context/content of my own into this? For example, I am trying to internally have conversations to move the company to Ramp? or I could download all of the context and the article and do it the other way around?