A recent paper from researchers at UCLA and USC detailed the deleterious impact of legalized gambling on consumers’ financial health, so we felt it was an apt time to republish Evan Armstrong’s article on how consumer products across industries—TikTok, diet apps, investing platforms, and, yes, sports betting platforms—have become increasingly addictive. Evan argues that as digital competition intensifies and technology inputs are commoditized, addiction has become a key differentiator and competitive advantage. But he also offers a hopeful perspective on how individuals can resist these addictive forces. When coupled with his piece from last week about consumers becoming addicted to AI chatbots, it’s clear that we’re entering a digital world that requires intention and care to navigate. He’s researching a framework for how to know when you should worry about addiction, but in the meantime, we wanted you all to read this piece to prepare.—Kate Lee

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

The first time I opened TikTok was the first time I was terrified by technology. At 9 p.m. on a Tuesday night in Southern Utah, I downloaded the app thinking I would check it out for five minutes. Then, without warning, I looked over at the clock and it was 3:30 a.m. I had been scrolling for six-and-a-half hours without pause. At first, I thought I had a stroke or the clock was wrong, but then I realized that I had just been laying in bed, flicking my thumb up the screen, my mind ignoring the passage of time. TikTok had grabbed control of me—body and mind. It was spooky.

The next day I tried to describe to my family what had happened and what TikTok was. After several minutes of failed explanations, I finally hit on something that felt right.

“It’s like TV on crack.”

It was the most addicting, dopamine-fueled app I’d ever used. Even the most chaotic reality TV show felt dull and slow in comparison.

My experience was not mine alone—the average TikTok user is on the app for 95 minutes a day. They open it eight times a day. The app is the third most used social app in America, topping Snapchat, LinkedIn, X, and Pinterest. It is used by over 1 billion people every month. Assuming a 50 percent dropoff from monthly to daily active users, the app consumes 84,608 man-years a day. This is just a mind-boggling amount of time collectively wasted by the human race.

Perhaps “TV on crack” was even an understatement of the service’s power. And it’s not the only thing that has gotten more addictive lately.

In 2010, the investor Paul Graham published an essay entitled, “The Acceleration of Addictiveness.” In it, he proposed that as technological progress continues its inexorable march forward, it will cause product improvements in every category. For the majority of products, that means they’ll become more addictive. Graham argues: “The world is more addictive than it was 40 years ago. And unless the forms of technological progress that produced these things are subject to different laws than technological progress in general, the world will get more addictive in the next 40 years than it did in the last 40.”

I would propose that this process of optimization has accelerated over the last decade. We are at a level of ultra-optimized consumer addiction of which TikTok is the exemplar. However, this addiction isn’t merely relegated to the realm of social media—it has penetrated nearly every category of product that consumers interact with.

As the world shifts to more digital competition, one of the most powerful long-term advantages is addiction. For businesses, this means that services that can grab and hold consumers’ attention for longer will be rewarded. For consumers, it means that we will have to be ruthless in our relationship with technology. Business best practices are not equivalent to consumer best interests. Whether professionally or personally, each of us will need to understand and reconcile ourselves to this phenomenon. In the years to come, whoever responds best will be rewarded.

This essay is an exploration of product categories where I think this trend is obvious, the reasons why I think it happened, and what we can try to do about it.

What are we selling here, anyway?

The impetus for this piece was actually pretty banal. As I was watching March Madness and the NBA playoffs, I kept getting slapped in the face by ads from DraftKings and FanDuel.

“WIN MONEY, HAVE FUN, IT LITERALLY CAN’T GO WRONG,” my TV would scream at me during every free throw attempt.

For the uninitiated, these are sportsbooks. They show ads during games to encourage watchers to place money on the outcomes. Weirdly, companies like this don’t actually try to make money from the outcomes of each game. The money comes from what is called “the juice” in the industry. That’s the fees books tack on top of each transaction. The real money is made in volume, not necessarily individual outcomes. Because long-term volume is more important than maximizing the potential revenue from a single bet, companies are incentivized to wrap their tentacles around their prey—sorry, users—and never let them go.

At first, I thought the reason consumers used sports betting apps was to make money. However, as I interviewed people for this piece, I realized that this was an entertainment product. In interviews, customers would mention that normal sports “became boring” and they couldn’t stop putting money down because it “made the game more intense.”

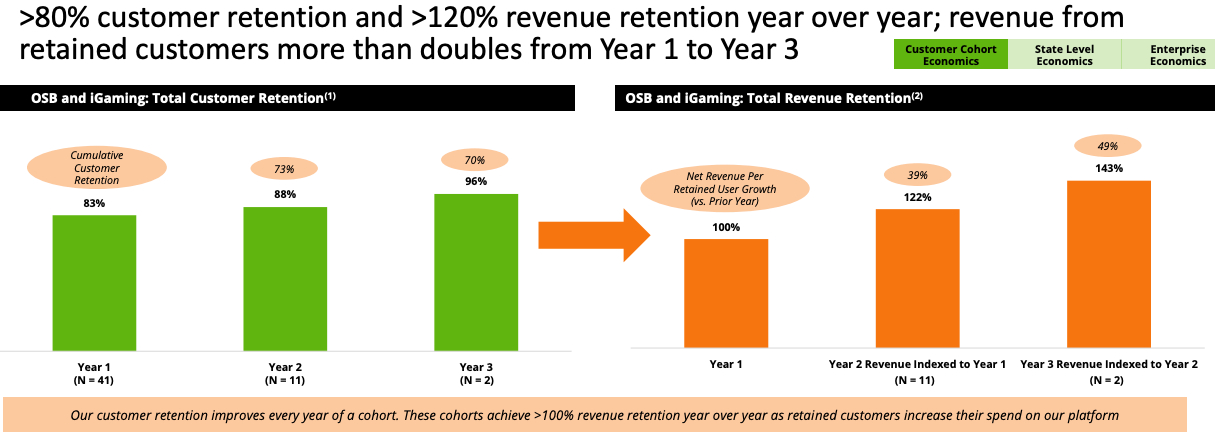

The numbers match the narrative I heard from these user calls. DraftKings looks for a two-to-three-year- payback period from each customer cohort while simultaneously boasting 83 percent first-year retention rates as of 2022. In comparison, research has pegged any retention north of about 60 percent as top-shelf. So there really is something very sticky about this business.

Keep in mind the proliferation of online gambling will likely destroy addicts' lives, create new gambling addicts, and just probably isn’t a great thing for society as a whole. Moral ramifications of online gaming aside, we can agree that this is a business that flourishes when more people put more of their hard-earned cash in, with absolutely no limits on how much they can take.

Source: DraftKings.

A similar pattern of layering gamification and higher retention onto existing markets via addictive products happened everywhere I looked. A few more quick examples:

Dieting: Making you feel bad about your body is an industry as old as America itself. In the early 2000s, this mostly happened through frozen meal services and diet plans like Jenny Craig and WeightWatchers. Twenty years later, those services still exist—but much of consumer attention switched to digital alternatives like MyFitnessPal, the design of which relies on gamified calorie counting to keep people engaged. A more recent iteration is Noom, a weight loss app that got going in 2016. It leans on the gamification lessons of MyFitnessPal but layers on an even deeper understanding of human behavior to encourage people to stick around. Rather than simply counting calories, Noom labels food as red, yellow, or green, sends push notifications when it thinks you’ll be tempted, and has you weigh yourself everyday. In response to a question about why they had so much growth in the app early on, the cofounder tweeted that, "investing a lot in psychology — both academic psych and even more importantly trying to figure out how those principles work in our product/real world. IMO, that’s a super power of our product, growth, data science teams."

There is nothing inherently harmful about deciding to adjust your weight or eating patterns. However, since Noom monetization is reliant on continual subscription renewal, and the app has a nasty habit of triggering eating disorders for some individuals. That said, this strategy has worked well for the enterprise—they generated over $400 million in revenue in 2020.

Investing: Investing online is an old business now. E-Trade created the first online brokerage for individual investors in 1992. Desktop-based trades stayed the norm until Robinhood launched its mobile app with no fees in 2015. The app was littered with design choices that prioritized gamification such as confetti for when someone made a trade. Robinhood makes money for every trade you make, not how much money you make, so the monetization mechanism is prioritized toward people making frequent trades. This is despite study after study showing that investors who day trade consistently lose money, while the most reliable strategy is a long-term index fund hold.

There were the apparent dopamine hits that occurred when a trader’s position went up, but that wasn’t enough. Now we have stock and crypto brokerages where you can achieve dopamine hits from trades across assets ranging from stocks to cryptocurrencies to NFTs. With many of the newer digital assets, you no longer have to wait for markets to open because trades are available 24/7. The dealer is always a swipe away.

Charlie Munger, the late vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway and Warren Buffett’s longtime business partner, said that even Robinhood was “beneath contempt.” He remarked, “It’s a gambling parlor masquerading as a respectable business… And it’s telling people they aren’t paying commissions when the commissions are simply disguised in the trading. It’s basically a sleazy, disreputable operation.”

Food: When you wanted to order take-out in 2010, you would usually just call your local pizza shop or Chinese restaurant. If you were lucky enough to live in New York, you could order via Seamless. Now, everyone everywhere can open up DoorDash, use a DashPass membership, and order the algorithmically suggested foods most popular near you. Notifications will pop up right at the time most likely to get you to order again. On the driver side of the network, delivery workers are encouraged to “keep their streaks going” and gamification methods encourage them to keep working past the point they would naturally want to quit. All of this has resulted in 37 million monthly active users with over 18 million paying subscribers to their membership program. Combining all of this activity the platform created billions of orders each year. This is a whole different animal than the Chinese takeout order of yesteryear. The business is predicated on frequent usage. And it isn’t necessarily better! DoorDash prices are frequently higher for consumers, restaurants hate it because it destroys their margins, and takeout is just, like, worse for you to eat than a home-cooked meal.

Corporate communications: Shoot, even in the most boring type of business in the world (B2B software), this trend manifests itself. Business software in the 2010s were mostly email clients and Microsoft Office. Google Docs started in public beta in 2006, but hadn’t reached the level of ubiquity that it enjoys today. Now, business software is hyper-opinionated and inherently multiplayer. Email clients like Superhuman proudly tout how they utilize game design to get you through your inbox faster. Slack launched in 2013 with GIFs, memes, and fun things galore to have you spend your day typing away. In pitches to companies, Slack’s sales people will often give stats on how often their app is used throughout the day by customers. Addiction is a selling point!

It is important to note that I don’t think all these newer companies are bad. Services that encourage more of certain behaviors aren’t inherently evil. All businesses would love for customers to use their products a ton. Personally, I love Superhuman and use DoorDash all the time! However, addiction is increasingly becoming the blood sacrifice required of consumers to allow businesses to win.

Imagine the competitive landscape for any of the apps above, whether diet app or food delivery service. If there were 100 similar services competing against each other, which one would you predict to win: the one with a great brand or the one with an incredibly addictive product?

Still though, how did all this come to be? What unique market conditions made addiction so important so quickly?

Why did this happen so fast?

If you’ve ever visited the tourist traps of the Americas, say Cancún, you’ll probably have visited the local markets where city residents set up stalls to sell to foreigners. There will be 50 or so of these booths, one after another, all with identical products, all with the same marketing. Tourists often delight in negotiating down prices and playing various vendors off of each other. There is absolutely no differentiation between any of the stores because they all have the exact same inputs.

Digital goods are increasingly like those sold in those markets. All of the inputs of software are increasingly commoditized, making it easier and easier to spin up a new product. In the early 2000s, if you wanted to build a software app you would need to have your own servers, optimize back-end architecture, build out your own payments system, and then actually code the damn thing. Now you can build pretty much the entire thing through APIs and services. Infrastructure is handled by Amazon Web Services, payments by Stripe, customer communication by Twilio, 3-D graphics by Unity.

I’m not proposing that you don’t have to code anything anymore; however, the universe of things where you can write differentiated code is continuously shrinking. Digital goods are using identical inputs to create their widgets, meaning differentiation can no longer come solely from the quality of the infrastructure. Now it must come from somewhere else. Maybe it is brand, maybe it is positioning, but rarely is it technology anymore. Soon there will be no 10-year competitive moats in software.

Simultaneously, we are entering a period in which the techno-economic paradigm is pretty entrenched. We are past the point where everything must be invented from scratch in software and are mostly improving on things that have come before. Best practice articles on game theory, optimized system design, and user growth are everywhere. There are formal and informal networks of mentors who teach the lessons of the previous generation of software to eager new entrepreneurs. The combination of stagnant technology plus sociological conditioning has created a class of digital entrepreneurs that have absorbed the lesson of the 2000 crash and the 2008 recession by the time they launch their first product. What won yesterday is table stakes today.

As the battleground of competition shifts to digital-primitive vs. purely physical we can expect for addiction as a competitive advantage to accelerate. When everything is identical, the best variable to optimize around is attention. Where we spend our time is typically where our dollars go. However, is this necessarily bad? Is technology being present in more parts of our lives always a bad thing?

Panic at the bicycle

When the bicycle was first invented, there was a huge moral panic about the impact of the new technology. People were concerned over whether it would cause resting “bicycle face.” Note: This may or may not be the origin of RBF. There were worries that riding bicycles caused disease, insomnia, and a host of other “maladies.”

There is always panic whenever a new technology is invented. Change is difficult, and new tech makes the future scary. My general take on the future is that if you could be teleported 100 years forward you would probably think it is grotesque—but it has always been this way. Sometimes things change faster than others so the exact “number of years until you’re sickened” varies, but you get the idea.

Dealing with a radically different future is more an exercise in understanding that people are capable of getting used to and living with a very wide variety of ways of being. Trying to fight this is like trying to fight urbanization—ya ain’t gonna win. All you can do is make things better within the new broad overall direction that history is pointed at, not shift the secular trend of addictive technology.

Another example from our recent past: When Nielsen first started measuring TV watching in 1949, the average American was watching four-and-a-half hours of TV per day. That number peaked at eight-and-a-half hours per day in 2010. It is super important to note that there is a huge difference in this number depending on race and income levels, but the trend of us devoting more and more of our free time to entertainment is directionally accurate.

Again, this feels icky! All of humanity plugged into a screen digesting whatever Hollywood has deemed fit to produce feels pretty gross. But that doesn’t mean it is illegal or a bad business strategy.

I’d summarize why this is all happening with two sentences—one academic version and one human-being version:

- Academic: System-level optimization will generally result in individual suffering.

- Human: Sometimes stuff that is good for a bunch of people will be bad for the one.

When an axis of competition is in a moral and regulatory gray area, the free market will reward those who exploit it to their advantage.

Almost everyone can agree that they would prefer to not be addicted to their technology, but that isn’t what wins market share. (If the topic of system-inherent suffering is interesting, I recommend the book Inadequate Equilibria.)

Said another way, I wish with every fiber of my being that Logan and Jake Paul’s content didn’t exist. We are all dumber for having to know who they are. However, my relatively high-brow newsletter doesn’t prevent the existence of their YouTube channel. Similarly, I desperately wish there was a fast-food chain that offered a healthy, delicious drive-through option. However, even if that store existed, it wouldn’t disrupt the garbage food disposal that is McDonald’s from being on every street corner.

The system rewards companies that keep their users highly engaged with their app and unless we dramatically change incentive and regulatory structures, there really isn’t much society can do about it beyond individual restraint and choice.

A note of hope

There is one argument that provides an optimistic interpretation of this trend. The world has always rewarded those with contrarian patterns of living. Being different from the system is painful and awkward sometimes, but it allows an individual a richer life (literally and figuratively). The more addictive our technology becomes, the more lemming-like our world will become, and therefore, the more richly rewarded the few remaining contrarians will be.

The action items to take from this essay would therefore be threefold:

- Go outside and touch grass. Continue to do so until the urge to open X disappears.

- Double- and triple-down on your individuality: Know yourself enough to know what is special. Improve that for years and years. Ignore everything else. Over time this will result in a version of you that is differentiated from the fairly predictably mediocre outcomes that come from following the established path.

- Carefully monitor and limit screen time: In 2018, I met Facebook executives who wouldn’t let their children on the service. No getting high on their own supply in their household. It might be worth considering doing the same by restricting when and how you use technology.

On that note, good luck!

Evan Armstrong is the lead writer for Every, where he writes the Napkin Math column. You can follow him on X at @itsurboyevan and on LinkedIn, and Every on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

As a product growth guy, this hit home. Great analysis, Evan 👏