Sponsored By: Stacker Studio

If you love reading Napkin Math, you know how I hate big tech taking nearly 40% of money from advertising and acquisition costs.

Stacker Studio fixes that problem by helping companies win in organic search through the creation and distribution of authoritative content to America’s top news networks. Stacker develops newsworthy, data-driven stories for you and distributes them through 3,000+ authoritative channels, including SFGate, Chicago Tribune, NY MSN, and Newsweek. They get hundreds of high-quality/SEO-friendly earned pickups and dofollow backlinks pointing to your site, valuable reach into new audiences, and meaningful increases in traffic over a 6-month pilot.

For Napkin Math readers, Stacker Studio is extending 10% off their list price for any new partnerships before the end of March.

One of the ways that I knew crypto was in the midst of a stupid crazy, eye-popping, slap-ya-momma-silly type of bubble last year was by the amount of leverage available to retail investors. If you aren’t a degenerate gambling addict (aka a Robinhood user), you may be unaware of how leverage works. This is where traders will put down some money and then a third party will loan them some multiple of that. When it works, it means you get to capture lots of profit on a larger position than you had the initial cash for. The formula is simple:

Outcome = (amount of money required to open a position) x (% price movement) x (leverage)

Basically, you are required to put down a certain percentage of an asset’s value, then the third party will give you some money to cover the rest of the position, and then you pray to God that the numbers go up. Trading using leverage acts as an outcome multiplier. Little moves in asset prices can mean big investment outcomes in either direction. Win big, lose big. Traders use this tool because it allows them to magnify smaller price movements (e.g., a 2% swing can be a big deal if you are levered up enough), but they also use it because it allows for an outsized impact. Investing is a scale sport, and if you don’t have lots of cash, using leverage allows you to trade as if you do.

In a simplified example, imagine having $1,000 to invest in a stock, then borrowing $100K to amplify your investment. If the stock goes up 5%, your gain is $5K instead of $50—but if it goes down 5%, your loss is also $5K instead of $50.

In a regulated, normal-world security market, the U.S. government enforces a 2x leverage limit. In contrast, crypto exchanges regularly offer up to 100x leverage. It is super, super dangerous to play with and at scale can lead to horrendous societal outcomes. The market crash of 1929 was partially driven by the rampant use of unregulated margin trades. There are numerous horror stories on Reddit of people losing millions over the course of several months using similar tools. Or as Warren Buffet said in 2010,

"It gets down to leverage overall…I've always said, ‘If you're smart, you don't need it; and if you're dumb, you shouldn't be using it.’"

Note: My finance professor at BYU once called Wall Street “Las Vegas for Mormons.” The faith of my forebearers famously prohibits gambling but you’ll still find my clean-cut Mormon brethren populating every major bank in the world, happily gambling away guilt-free on the stock market. I wonder what percentage of crypto trades are done by Diet Coke-shotgunning former missionaries?

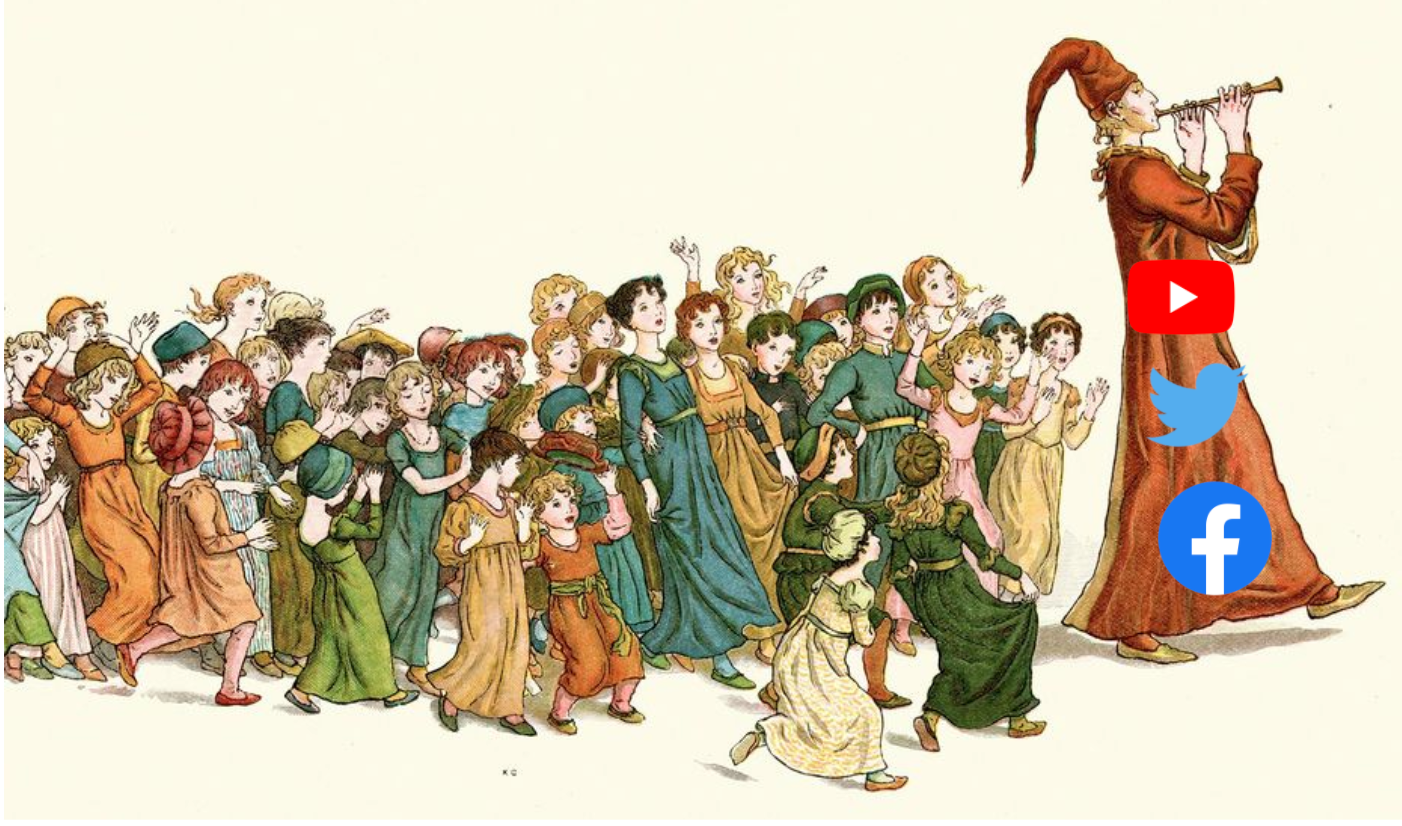

That unsophisticated investors have 50 times more leverage available in crypto versus stock markets is, to me, a clear indicator of an asset class that is so wildly volatile that it obviously hasn’t settled into the more understandable rhythm of traditional investments. You could argue that this craziness is the result of ponzi schemes, lack of inherent value, early market jitters, or whatever, but I think a part of it is the result of an undiscussed power of the internet—leveraged thoughts.

The formula I described above is by necessity translated into the terms of single security purchases. However, I propose that is there is another somewhat fuzzy version of this formula for leveraged thoughts. The formula would look something like this:

Power Output = (An Idea) x (Number of People Who Believe It) x (The Power of The People Who Believe)

Let’s walk through each term in this equation, and note how it is similar to the equation for leveraged trades:

- Power Output = The resulting actions, fiscal or otherwise, that come from an idea. For today we will mostly discuss finance/business thinking because, well, that is what I write about. But it holds true for all sorts of ideas! Much of social change and improvements in government can be traced to ideas that were leveraged. Thomas Paine’s Common Sense was a mass-distributed pamphlet by an anonymous author that helped catalyze the American Revolution. The power output could be measured in revolutions or returns, but the key component is that the output is much bigger then if some thinker just used the idea on their own.

- The “Idea” = What you bring to the table. Ideas on the internet can be anything from a meme to naming an important new category of business. This concept is similar to the first term in the leveraged stock trade equation (“amount of money required to open a position” or % purchase price of a security covered by cash or collateral). Ideas qualify because the only capital they require is intellectual and reputational—all you are risking is that your idea will be wrong. There is no financial requirement.

- Number of People Who Believe It = “% price movement” in the original leverage formula. Like I said, this is a somewhat fuzzy equation! But in the first formula, small movements in the price have large impacts. Leverage provides scale and thus juices returns. Similarly, we continually underestimate the scale of eyeballs that accompany publishing on the internet. The internet is the ultimate attention leverage ever conceived. A relatively minor change spread out over tens of thousands of people results in massive real-world implications.

- Power of the People Who Believe = Leverage. Ultimately, the bigger the concentration of power that accompanies an idea, the more impact it will have. If the audience that receives an idea is truly powerful (whether via capital, politics, or otherwise), they can magnify the idea. Similarly, the more leverage that accompanies a trade, the more outsized the outcomes will be. To optimize idea leverage, individuals will want to target an audience that has the power to effect the change they are advocating.

The internet is beautiful because it is rooted in an ideological egalitarianism, an environment that allows for a free exchange of ideas. Whether President or pole dancer, everyone types in the same URL and hits enter. This means that ideas can go both further, in terms of reaching more people, and deeper, in that they can penetrate powerful elite institutions. If you write something well enough, and it somehow reaches the right person, an idea can suddenly take on a life of its own. Essentially, you can be loaned power on margin by means of the size and power of an audience you publish to. You provide the initial intellectual capital, and the idea takes a life of its own from there.

Crypto is one of the most prominent examples of the leverage that occurs with the internet. Digitally native currency that works without third party approval is immensely, scarily powerful on its own. Couple that with tens of millions of believers that have capital to burn, and the result is a highly leveraged idea. Part of the reason crypto has such wild price swings and so much leverage available is because of the volume and power of its believers.

However, idea leverage isn't just constrained to the weirdness that is crypto. Take for example Dr. Michael Burry of the movie “The Big Short” fame.

One of these is Hedge Fund Manager Michael Burry, the other is a famous actor portraying him. Can you spot the difference?

While he is most popularly known for his insight that there was a bubble in the housing market, I’ve always thought the most interesting part of Burry’s story was how he got to the point of managing money. Before the hedge fund tomfoolery began, Burry was a graduate of Vanderbilt’s School of Medicine, and was completing a residency in pathology at Stanford Hospital. On nights and weekends, he posted on the stock market discussion site Silicon Investor. From the period of 1996-2000 he posted 3,304 times or about ~2x per day. This was the “original idea” component of the equation. As his audience grew, he attracted more and more attention from companies like Vanguard.

Finally, at the end of 2000, he opened his fund Scion Capital. Author Michael Lewis described his breathtakingly incredible performance:

“In his first full year, 2001, the S&P 500 fell 11.88%. Scion was up 55%. Burry was able to achieve these returns by shorting overvalued tech stocks at the peak of the internet bubble. The next year, the S&P 500 fell again, by 22.1%, and Scion was up again: 16%. The next year, 2003, the stock market finally turned around and rose 28.69%, but Burry beat it again, with returns of 50%. By the end of 2004, he was managing $600 million and turning money away."

Burry’s ideas resulted in him managing $600M within 8 years of posting online.

$600M = (Stock Picks, 3000+ posts [upfront capital]) x (SiliconInvestor.com Readers [% change]) x (Vanguard + Other Wealthy Limited Partners [leverage])

Again, this happened for a guy who had no background, no experience, and no connections outside of his connection to the internet. Burry’s story is especially poignant in comparison to the situation of a typical employee.

Help, I’m being exploited and I can’t rise up.

If you are a talented analyst, at some point you will be held back by the mistakes of the people managing you.

You will create some novel piece of insight that starts to climb the corporate ladder. Your manager rubber stamps the analysis, their boss adds comments (none are useful), and then passes it up the chain. Up and up until it hits someone's desk that doesn’t like the idea. It gets killed, and into the dustbin your genius goes. Unless you somehow manage to skip up to the very top, there is a series of gatekeepers that will prevent some ideas from ever seeing the light of day. Additionally, it is necessary to account for workplace politics, so you have to make sure the analysis you deliver gives executives the results they want (and usually the result they want is you telling them how brilliant they are). Note: To my former bosses who read this, I’m talking about my other former bosses—never you, baby.

The downside of being an in-house analyst/thinker/researcher/take-your-pick-of-title-that-designates-a-person-who-is-paid-to-think is that not only is the reach of your ideas limited by the company’s power, but you also have to get permission from multiple stakeholders for your idea to exist within those limits. Unless you get bold and send it right to the top, your idea can only make so much headway on merit alone. It transforms the idea leverage formula into an IF statement:

Power Output = IF (Political Approval = “True”, ((An Idea) x (Number of People Who Believe It) x (The Power of The People Who Believe), Political Approval = “False”, Unemployment)

On the other hand, there are upsides to in-house ideas! When the correct people are convinced, they can shift many people’s full-time attention with a snap of their fingers. However, leveraging thoughts inside of organizations is a very power-constrained, politically dependent game. Companies are wonderful places for stability, benefits, and friendships. They are terrible places to be geniuses.

However, there is one last problem to address with the concept of idea leverage: capture rate.

Get Smart and Get Poor

The current idea leverage formula for Napkin Math’s writing on the VC market looks as follows:

Power Output = (Post) x (~20K Readers) x ($50B+ in Active VC Funds Under Management By Readers)

Every time I write about a tech company, investors get an in-depth analysis hitting their inbox for the cost of ~$240 a year. (If you would like to subscribe, I’m doing a piece about Twitter next week behind a paywall). My insights on Twilio, SurveyMonkey, Notion, Netflix, and many others have likely been used to make lots of money for my readers. Readers can realize, “Oh wait SurveyMonkey is in real trouble, so I should short them,” and then take action accordingly. (The price is down 31% since I wrote my piece.) Readers can use my ideas to make investments using the collective $50 billion they have to deploy. Note: When I did the math and arrived at the $50B number, I was/am flabbergasted. Like I’ve said many times, writing on the internet is crazy! Hello billionaire readers!

On the one hand, that is wonderful! I am stunned that so many of my investing heroes read and pay for my work. On the other hand, this sucks! I have not made millions of dollars from my insights. My list is full of top Silicon Valley M&A executives, YCombinator founders, and many, many FAANG VPs who potentially use my frameworks (like last week’s on Platform-Proof Creators) to direct the work of thousands. Again, cool that my ideas could be used that way. But also—bad for me. I don’t even have an intern!

The leveraged idea is wonderful because it means that ideas are unconstrained in their influence, but that is not the same thing as the inventor being rewarded for the creation. This same problem is also present in companies: if you are salaried, you are not compensated for idea impact in the slightest.

There are essentially only 3 methods by which to increase an idea value capture rate:

- Monetize the attention: This is the newsletter play. Whether via ads, gated communities, or subscriptions, turning people’s eyeballs into money makes sense. However, this only kinda works (trust me). This model incentivizes creators to make things with the widest mass appeal instead of the highest quality. Additionally, you aren’t actually capturing any of the value that your idea is generating. You are just capturing the value of the attention that accompanies a truly great thought.

- Reputational Gains: Reputational capital is fickle but real. Consistently using idea leverage allows the thinker to accrue residual reputational power. Over time, this net reputation given to the creator can be funneled into something interesting. In my own creator journey, this has been particularly surprising to me. I still see myself as a guy writing in the basement of a Salt Lake City condo, just one mistake away from total ruin—but others view me as an “expert.” Some people ask for my advice and are willing to compensate me for it. The contrast is extreme.

- Gain Power: The most effective method of idea leverage is to increase the power concentration of the creator by raising capital or organizing people to invest in an idea. It makes sense: if the idea is good, you should profit from it yourself. However, this is exactly why stock-picking newsletters sometimes have a bad reputation. If you know so much, why bother trying to sell what you know to other people, rather than just monetizing it directly? The reality is that most people write for writing’s sake. Personally, I genuinely love and enjoy writing about companies. One day I’ll deploy capital based on my ideas, but for right now I’d like to focus on my writing and creating. Additionally, raising a fund or convincing people to work for you is incredibly hard to do. It is doubly hard for a creator to do so because financial outcomes always lag attention. You can publish ideas for a long time before starting to truly make real money from them. Getting capital is always more difficult than first estimated.

By proposing the framework of idea leverage, my hope is that you’ll be able to recognize when your power is being leveraged by a creator. It should be clear when a creator is trying to leverage your influence and capital for their gain. Cough *NFT scams* cough. Simultaneously, as more and more people attempt to become public intellectuals, it should be done with the recognition of how much power an idea can have on its own.

When the original Bitcoin paper was published, it is unlikely that the author understood that one day the entire United States government would be concerned about how crypto could be used to escape sanctions. When Q started publishing on 4chan it is unlikely that they predicted their dumb little rants would lead to the storming of the US Capitol. The internet is the leverage machine and no creator knows how far their ideas will go.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.08.31_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!