Sponsored by: Every

Elevate your performance with mindfulness

Don't miss out on special pricing for The Hidden Discipline for Every subscribers.

This eight-week mindfulness course is designed specifically for busy, high-achieving individuals looking to unlock the "hidden discipline" that can transform their lives. Through live sessions, daily practice, and expert guidance, you'll gain the tools to:

- Power through challenges with greater resilience

- Handle stress with ease and clarity

- Fully savor life's best moments

- Be more present and effective in every area of your life

Every subscribers can enroll for just $799—a 20 percent savings—by using code “EVERY” at checkout.

Take advantage of special pricing and unlock your full potential with The Hidden Discipline today.

Want to sponsor Every? Click here.

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

Over the past few weeks, new AI-powered hardware has been released to less-than-kind receptions—the Humane Pin was lampooned and the Rabbit R1 was skewered. While some people enjoyed the devices, it is safe to say these were not the launches the companies had hoped for. At the same time, other startups have raised millions in venture capital to build new consumer hardware devices. Investors I know are actively looking to deploy money into the category, and Sam Altman and Jony Ive are in talks to raise up to a billion dollars for a consumer hardware device.

This disparity raises so many questions: Why are these new devices being received so poorly? What do founders and investors believe they’ll get by betting their careers on this difficult and clearly uphill battle? Will their bets actually work?

To figure out the answers, I’ve been in the weeds with founders, talking product roadmaps, capital strategies, and levels of excitement. Here’s what I learned.

Why is this hardware’s moment?

The reasoning behind the rapid new launches and investor bets is simple. It’s AI.

Many see AI as a technological paradigm shift akin to jumping from personal computers to mobile computing—and there is a chance that a new Apple could be built. With Palo Alto’s favorite fruit-centric company currently enjoying a $2.68 trillion market capitalization, people are feeling like Louis Armstrong did when he touched a trumpet for the first time (quite jazzed).

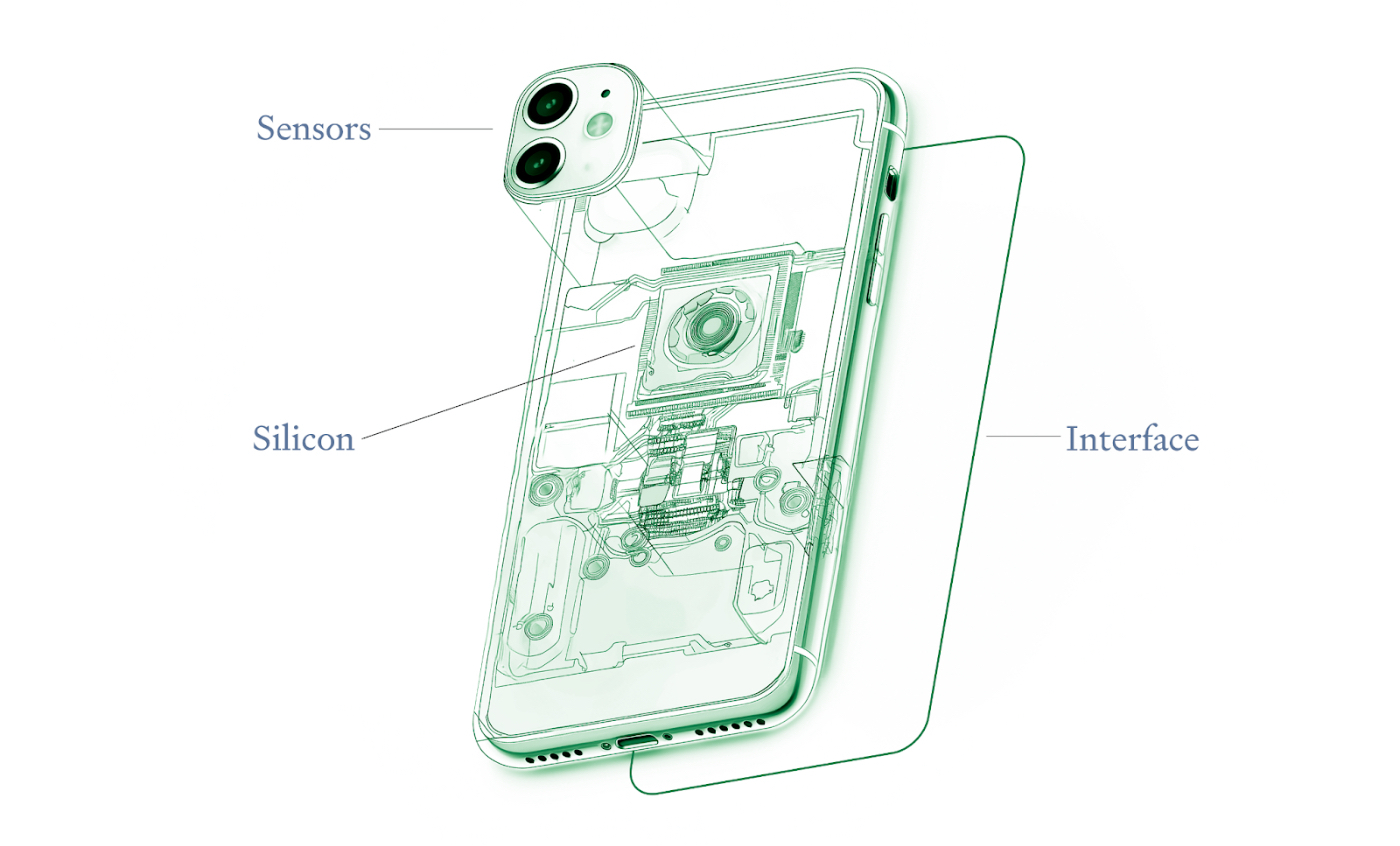

I’ve previously argued the components of a hardware device can be broken down into three groups:

- Silicon: The chips running the computation for the device

- Interface: How you, as a user, interact with the device

- Sensors: The instruments providing data to the software running on a device—cameras, accelerometers, a GPS, a heartbeat sensor, etc.

New consumer devices are emerging because AI allows you to use the sensors, silicon, and interfaces developed for smartphones in novel ways. AI can take the input of large amounts of ambient data, such as the audio from your conversations and your behavior as you use your computer. Then, AI can output unique insights based on that corpus of data—much more personalized, sensitive, and accurate than what regular software can do today. It can also leverage existing data for new actions, such as following voice commands more closely. Basically, it’ll listen to what you say and bring out smart stuff that you missed.

While my description may be banal, the possibilities are exciting. Smartphones are dominant, but aren’t perfect. Consumer addiction is—at least in my estimation—largely due to the monetization of smartphone app stores and the form factor of the device. If AI can evolve our relationships with devices, it’s a meaningful change. An AI ambiently crunching data and performing tasks without the distraction of a screen is net good for humanity. And, as a happy capitalistic coincidence, it would probably make the inventor of said device the owner of several large yachts.

So if the promise is so wonderful, why is the category so challenging?

The problem of the iPhone

The answer is, once again, simple: The iPhone is too damn good.

If I asked you to visualize what the iPhone disrupted, you’d probably think of an image like this—a brick cell phone, a digital camera, a GPS.

Source: CNET.Apple’s disruption happened because it brought the sensors in all these devices into one form factor. Since the iPhone had a powerful chip and a multi-touch screen interface, it became a catch-all device that does pretty much everything pretty well. Sure, it isn’t perfect—the Kindle exists—but the smartphone is so incredible because the interface is flexible enough that it can do a good enough job at essentially everything a consumer needs.

Source: Every illustration.Apple has spent 18 years and hundreds of billions of dollars stuffing ever-better components into ever-more-powerful phones. Its market dominance has yielded a supply chain and manufacturing partners that a startup can’t hope to match.

An AI hardware company is in the unenviable position of having inferior sensors than Apple, generic silicon chips, and a grand total of zero developers in its ecosystem. It is very, very hard to compete with an iPhone when every piece of hardware you have access to is worse. So these companies have to try to innovate on the interface. My current favorite AI hardware device, the Meta Ray-Bans, eschew multi-touch glass in favor of voice activation. The R1 has a scroll wheel, and Humane uses a laser projector.

When you’re playing with these odds, your best bet is to differentiate on the software—not the hardware. Which means that, basically, most consumer AI hardware should just be an app. One founder told me as much: “My company should probably just be an app, but hardware sounded more fun.” While this statement may be true, customers do not particularly care about how good of a time a CEO is having.

And if AI is what has gotten the market so excited, it should be the competitive edge, too. Both Rabbit and Humane’s products have been reviewed so critically because while the hardware is beautiful, they are less powerful and generalizable than the smartphone. And in both devices, the redeeming factor of AI doesn’t actually work—large language models are not good enough yet to be virtual assistants. The hardware was rushed to market before the AI was ready. As popular reviewer Marques Brownlee, aka MKBHD, said:

“This is the pinnacle of a trend that's been annoying for years: Delivering barely finished products to win a ‘race’ and then continuing to build them after charging full price. Games, phones, cars, now AI in a box.”

But if we wait for the AI to be “ready,” we’ll run into more problems. It is incredibly expensive and challenging to differentiate on the basis of AI models. Like I just wrote, open-source can now provide GPT-4-levels of performance, so startups have to train a model to do something no other open-source model can—adding scientific research to the many hurdles that they’re trying to conquer.

What happens next with AI hardware?

To be clear, I very much want these companies to succeed. As a red-blooded capitalist, I love competition. To compete with Apple, AI hardware companies have three paths:

- Get weird with it. Explore use cases that are fundamentally different from smartphones. By focusing on markets where phones have proven ineffectual, such as healthcare or manufacturing, companies can carve out a space for themselves. Experimenting with unconventional interfaces like brain-computer interfaces, haptics, or augmented reality could also help them stand out.

- Go screen-free. Develop AI-powered devices that primarily rely on voice interactions, such as the Meta Ray-Bans. Ironically, Humane may have been right on this count.

- Rely on the phone. Rather than trying to replace smartphones entirely, focus on using the smartphone’s silicon and interface, with a hardware component acting as a supplemental sensor to gather data. Tab and Limitless are taking this approach: They sell an extra sensor, but the software lives in the cloud, and the hardware requires a connection to a phone via Bluetooth.

Venture-backed startups have an over 90 percent failure rate. These companies' struggles and long odds are a feature, not a bug. We should be cheering for every single founder trying something new. There is a viable path! But it requires something wholly new and different. Startups doing the same-old end up with the same-old result—failure.

Evan Armstrong is the lead writer for Every, where he writes the Napkin Math column. You can follow him on X at @itsurboyevan and on LinkedIn, and Every on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.08.31_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

This is a good read! Though I think it's valuable to understand the AI hardware dilemma, I liked the word at the last.

"There is a viable path! But it requires something wholly new and different. Startups doing the same-old end up with the same-old result—failure."

My learnings: https://glasp.co/kei/p/02507121a113a15070fa