Sponsored By: Bill

This essay is brought to you by Bill. Download their free “Ultimate Guide to Accounts Payable Automation” and learn how you can reduce bill pay time by up to 50%.

For nearly 100 years, there was no more important technology conglomerate than GE. A brief list of its inventions includes: the carbon filament lamp, the central power station, the X-ray machine, the first voice radio broadcast, the electric cooking range, the American jet engine, the first commercial nuclear power plant, the washing machine, man-made diamonds, the toaster oven, and 100 other devices. Its technology has been deployed on the battlefields of World War II, the kitchen of a suburban parent at dinnertime, and the silicon rubber in Neil Armstrong’s astronaut suit. In the nineties it was the most highly valued company in the world. To like the company was to like apple pie, baseball, and red pickups driving through a cornfield. GE was America, and America was GE.

Now, after nearly two decades of underperformance and decay, the conglomerate will be broken up into the only three remaining businesses of value: healthcare, aerospace, and energy. How did it come to this? And perhaps more importantly, when will it happen to the tech giants of today—as it inevitably will. Just as GE felt untouchable in the nineties, so do Apple, Amazon, and other tech giants feel now. But the second law of thermodynamics comes for everyone. Entropy will rear its ugly head, and a new corporate king will be crowned.

This question feels especially poignant with the recent swath of tech layoffs. Announced cuts so far include 12,000 at Alphabet, 10,000 at Microsoft, 18,000 at Amazon, and 11,000 at Meta. This is the most definite sign of weakness from these companies in over a decade. Should investors be concerned?

To determine the answer, we need to study how GE got to where it is today.

The best book to read about GE is Power Failure: The Rise and Fall of an American Icon by William D. Cohan, which was published in late 2022. The book excavates the history of the company in painful, excruciating, exacting, sometimes exuberant, 748 pages of extensively footnoted detail. It is accepted strategy theory that generational companies can be built off of flywheels, as GE did—but what happens when they spin for too long?

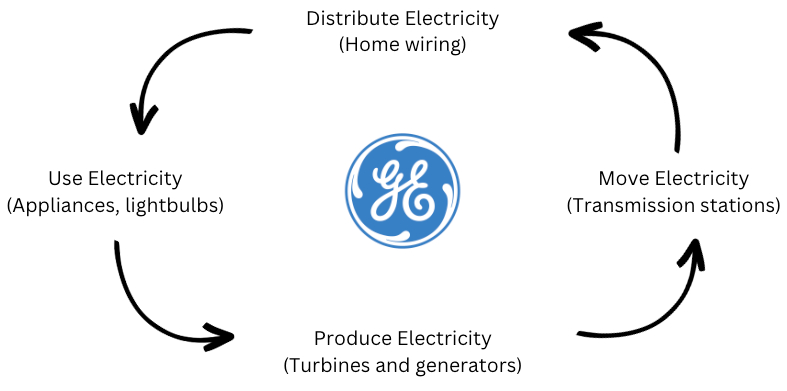

Electric flywheel

There are two ways to evaluate GE: as a business with the typical considerations of cash flow, profit margins, and the like, or perhaps more accurately, as a vehicle to enable a couple of old white dudes’ hubris. Let’s start with the first.

General Electric was incorporated on April 15, 1892 in New York City. The company’s creation was a somewhat unhappy marriage between two companies: Edison’s General Electric and the Thomas-Houston Electric Company. Based on the fame and fortune of Edison, you may assume that Edison’s company was swallowing the THEC, but the opposite was true. By the time the merger occurred, Edison had the firm impression of a heel on his backside: GE’s financiers orchestrated it as a way of giving Edison a boot out the backdoor and politely retiring him. How the famous inventor of the lightbulb lost control of his own company to spreadsheet jockeys is instructive to GE's evolutions over the next 100 years. The cycle of invention to money management will inform the rest of this piece.

Whenever a new technology paradigm emerges, 99% of people call it crazy and the 1% of weirdos known as founders see it as a business opportunity. Usually any time a scientific discovery occurs or a new market unlocks, a small but ferocious group of entrepreneurs will lock horns and battle for supremacy. Facebook was far from the first social media site (remember Myspace and Friendster?). Apple was far from the first smartphone inventor (remember Blackberry and Nokia?), and Amazon was far from the first e-commerce store (RIP pets.com). These battles are only partially decided by scientific advantage—things like firm culture, business strategy, and execution make up the difference more often than not.

In the case of THEC vs. Edison, the strategy was somewhat similar. They were both fully verticalized electricity companies. They both sold the dynamos, the wiring, and the various endpoints of electricity use—all of the things that made lightbulbs and electric streetcars usable. To grow quickly, they both rapidly acquired or financed smaller operations, introducing a significant need for capital. The merger was instituted so that these two giants would quit battling over the same customers and obtain more economic efficiency. Edison, for all of his inventive prowess, was not known for being a particularly talented operator—THEC was to be given operational control.

This story—of new technology to rapid growth to spreadsheet optimization to financial wonkery—is the defining one of GE. Over and over and over, from the radio, to chemicals, to the air conditioner, GE would do something similar. The company would use its might to buy its way into a new technology market, run with it for a while, and then corporate headquarters would start to fiddle with the numbers.

All of this very interesting coverage takes place in the first 25 pages of the book, which is a shame, as it’s the best part of the story. Cohan spends chapter after chapter discussing the personality flaws of various GE executives that I just couldn’t bring myself to care about. I would've loved more on this early time period.

The strategy theme at the center of the book—and of GE—was a flywheel that the company called the “Benign Circle of Power.” It looked something like this:

GE’s founding in the midst of the Industrial Revolution allowed it to be at the center of the rise of electricity and all of its subsequent use cases. Over and over again, an adjacent application they built to service the flywheel would turn out to be a massive business. Take GE’s move into chemicals. The company needed highly performant electric insulators for its turbines, forcing it to develop the chemicals themselves. Then, begrudgingly, the company moved into the new market and spun up a separate division that went on to do $6.6B in sales in 1998.

Another interesting development of the Benign Circle of Power was how much of the diversification was prompted by the U.S. government. GE would build something and be unable to visualize its value until some government bureaucrat prompted them to reconsider.The jet engine division, one so big and strong that it is one of the three business lines that survives to this day, wasn’t even GE’s idea! The U.S. government asked for GE’s help with converting the turbines it manufactured into superchargers for airplanes.

You can essentially track any weird asset that GE ended up holding to the Benign Circle of Power spinning out of control. A good example is how the company ended up owning NBC (the first time). GE’s scientists had invented the alternator, a key piece of technology for radio transmissions. The company didn’t even want the damn thing—it was actively trying to pawn it off to the British. It would have rather been focused on the manufacturing of the equipment that radio stations would need. However, the U.S. government stepped in and blocked the sale. GE was cajoled into starting the Radio Corporation of America, which was a holding company for GE’s radio-related assets. As part of that, almost as an afterthought, the National Broadcasting Corporation, or NBC, was created.

If you squint your eyes and tilt your head, you can visualize GE as a tracking mechanism of the United States’s technological GDP. As tech took over more of the economy, so too did GE get bigger. As the power cycle kept going faster, more assets cropped up. Eventually we get to the early 1980s, when the company had over 120 businesses, $28B in revenue, $1.6B in profits, $1.5B in cash, and a $12B valuation. Cohan covers this portion of the company's history in the first 157 of the 748 total pages.

The rest of the book is mostly devoted to the exploits of the two subsequent CEOs, Jack Welch and Jeff Immelt. Year by year, the book covers in excruciating detail what happened at the business. Welch took the company to its heights, and Immelt abided over its relatively swift decline. The remaining 591 pages are a case study of these two men and which one is to blame for the fall of GE. Did Welch build a house of cards, or was Immelt the incompetent fool?

And with that, we return to the topic of old white dude hubris.

How did it all fall apart?

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.08.31_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Can we stick to finance/business and refrain from Twitter-level stuff more fitting a deranged DEI major like “white dude hubris”, “fatphobic” etc. These people lived in a very different time, and applying 2023 zeitgeist to them, massively diminishes this otherwise excellent piece.

@tim550550 100% agree. That was kind of throwing me off.

Didn't realize Lance Armstrong also went to space :P

@prakhar.mehrotra dumbest typo of my life :( fixed!