TL;DR

- OnlyFans’ recent troubles are a part of a general phenomenon that happens at every kind of creator platform, social network, and media company: the content moderation double-bind.

- This double-bind explains why all companies dealing with content creators have such a challenging job controlling content: the closer a piece of content comes to the line of what’s outlawed, the more attention it will likely attract. But the more attention creators attract, the costlier it is to moderate their work.

- Different types of companies deal with this double-bind in different ways, but this basic phenomenon explains all sorts of success and failure in media.

Networks of user generated content (UGC) tend to be highly desirable businesses. In plain English, this is when users create stuff and then share and display it via your technology. Investors are willing to pay a steep premium to own a piece of these companies, because their network effects keep content creators and consumers coming back. Think of the premium Facebook, Snapchat, Twitter, and their social media ilk command on the stock market.

There's just one problem: the content moderation double-bind. We know that content moderation—typically a combination of AI and human moderators tasked with flagging and in some cases removing content that violates a company’s policies—is a semi-impossible task, but the situation is direr than most investors appreciate. And when you understand the true nature of the problem, you see how it applies more broadly than just UGC networks but also to traditional publishers and really any kind of company that involves media.

To truly understand the challenge of content moderation and the double-bind it puts platforms and publishers in, we need to start by questioning some basic assumptions many people have about what content needs moderating. When you hear stories about Facebook's contractors housed in anonymous office parks facing the worst of humanity, the popular understanding tends to assume that the only content that needs moderating is the stuff on the margins, that most people don't want to see and isn't very popular, but nevertheless needs removal. This is the stuff of extreme violence or sexual assault.

Actually, something like the opposite is closer to the truth.

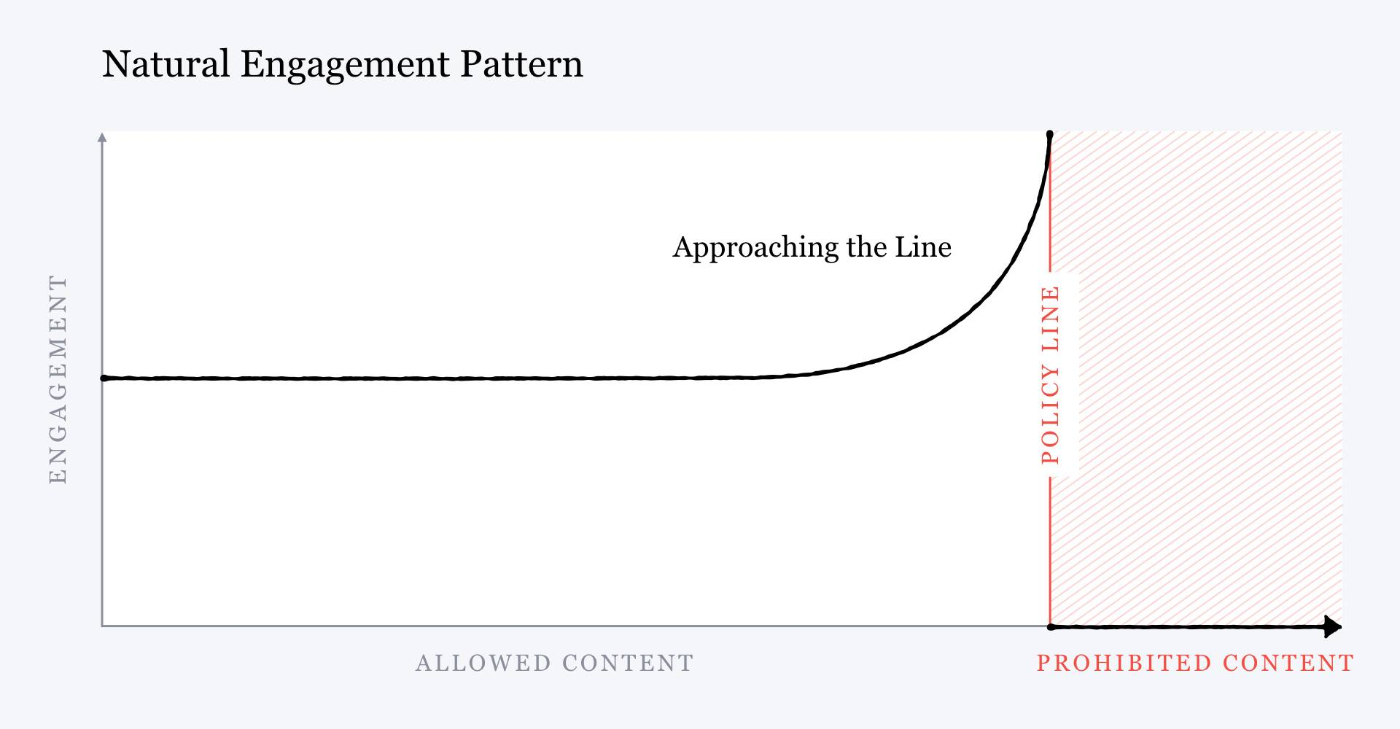

In a 2018 Facebook note, Mark Zuckerberg wrote,

“One of the biggest issues social networks face is that, when left unchecked, people will engage disproportionately with more sensationalist and provocative content. This is not a new phenomenon. It is widespread on cable news today and has been a staple of tabloids for more than a century. At scale it can undermine the quality of public discourse and lead to polarization. In our case, it can also degrade the quality of our services.

Our research suggests that no matter where we draw the lines for what is allowed, as a piece of content gets close to that line, people will engage with it more on average [emphasis added] — even when they tell us afterwards they don't like the content.

Interestingly, our research has found that this natural pattern of borderline content getting more engagement applies not only to news but to almost every category of content. For example, photos close to the line of nudity, like with revealing clothing or sexually suggestive positions, got more engagement on average before we changed the distribution curve to discourage this. The same goes for posts that don't come within our definition of hate speech but are still offensive.”

Zuckerberg accompanied his comments with this chart,

When you’re analyzing any business that deals in user-generated content, this chart should be the first thing that comes to mind.

Content creators on your platform will, as a whole, act as an evolutionary system naturally toeing their way ever closer to the line. If your content consumers are anything like Facebook's users (read: the entire freakin’ planet), then the content that's closer to the line will be rewarded with increased attention. This results in a content Darwinism where the edgy thrive. The people who don’t create content that’s close to the line tend to either pivot towards the edge, go out of business, or hit an audience plateau earlier than they would have if they were more shameless. Note: There are always exceptions to this, but that is what they are, exceptions.

And it isn’t restricted to the written word. Youtube’s most popular creators generally thrive off of drama and crossing the line. Logan Paul filmed and cracked jokes about a suicide victim in Japan despite his audience being largely children. David Dobrik was accused of enabling, filming, and monetizing a video of a sexual assault. It also works in the B2B context! Basecamp controls a large part of software culture by writing rants about things they don’t like and neatly translating that into software sales. Founders Fund is a top-performing venture capital firm while seemingly all of its employees are rude to people on Twitter (and get deal flow from that trolling!).

If you're paying close attention, you might have noticed this phenomenon has an important corollary for platforms and publishers: no matter where you draw the line, your content moderation decisions will put you in a double-bind where you can't win. Double-bind content theory is that the edgiest content will be the one that garners the most attention, however by virtue of it being edgy it will have negative social outcomes and thus negatively impact business outcomes.

The most popular content and creators will be flirting with the line, and you will experience pressure to let it slide by. If you stand firm, you risk losing them to more permissive platforms. You’ll also lose out on the revenue that the content would have generated. If you let their content go through, you risk having to testify in front of Congress (Facebook), or getting pressure to shut down by your banks (OnlyFans), or some other kind of repercussion.

Of course, all companies are somewhat beholden to their most powerful customers. In my homebase of B2B software, this usually just manifests itself as building out custom widgets for big clients. When you deal with content, your most powerful creators may ask for special business deals, but they will also demand special content treatment. Whether it is by virtue of them explicitly contacting the company for this privilege or whether the company feels this pressure from their business model, it is a very, very real phenomenon. As a recent example, OnlyFans did this exact thing by having an official company policy that allowed popular accounts to get away with posting content that violated its terms of service. Facebook did this by allowing conservative commentators special moderation privileges and allowing them to ignore their community standards.

Some argue that this is an ad-based revenue problem, but I am not so sure.

The new wave of creator platforms are generally focused on non-ad based revenue. Without pointing fingers (*cough* Substack) they argue that subscriptions, merch, and courses will make the work they host less subject to the content escalation problems then ad-based revenue. I am increasingly of the opinion that it actually does the opposite. Ad-based revenue lowers the barriers for consumption of content. Keeping things free makes it possible for boring, non-sensational content to exist. More people may watch Logan Paul videos, but Youtube, by virtue of its ad revenue, can also play host to all of the math tutorials I watched in college.

Edgy content ad revenue will subsidize the valuable content that doesn’t attract eyeballs. Subscriptions means the customer has to passionately want to engage in a small selection of material. There is no room for boring content subsidies. This is the reason that heated diatribes are the most popular newsletter genre on Substack. Finding the consistently edgiest take possible will generate the largest audiences over time.

As a writer on the internet, I hate that this is true! I do my best to keep my creative integrity and write about the things that interest me. But it is very hard to not just write about big companies' earnings and only engage with issues everyone gets excited about. As an example, I wrote a super detailed pricing strategy guide that received fairly minimal (for me) traction. My piece about Why You Probably Shouldn’t Work at a Startup generated 45x more subscriptions despite being decidedly less useful.

The Double Bind’s Implications

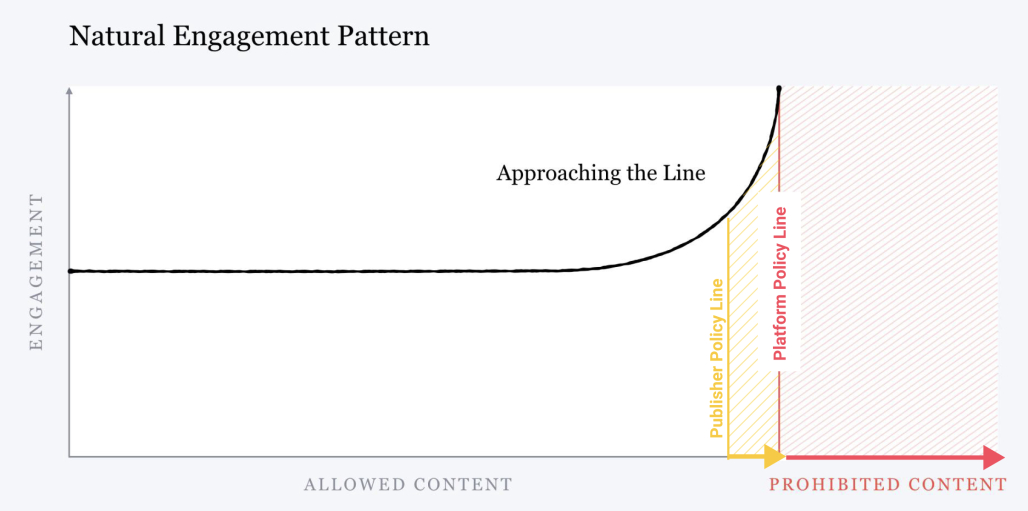

The closer that a company positions itself as a tool versus a consumption platform, the less they have to worry about the content double-bind. Adobe doesn’t take responsibility for racist memes made using Photoshop. Excel doesn’t worry about falsified financial documents created in their spreadsheet. Facebook, Substack, Twitter—all of these companies will argue that they are a tool or a platform, not acting as a publisher. Note: IMO while they aren’t analogous with a traditional publisher they weigh more heavily in that direction. The key to staying a tool is to avoid the dual trap of being an algorithmic recommender of content or being a direct funder of the person doing the creating (through loans, grants, or otherwise).

This is perhaps the greatest competitive trick social platforms have ever pulled. Analysts like to focus on the network effects, scale, and recommendation algorithms that give platforms a competitive advantage over traditional media companies. But in the market for attention UGC platforms have an additional core advantage that is massively under-appreciated: they have a narrative that attempts to absolve them of responsibility for what they publish. This is where Section 230—the law keeping platforms from being liable for content they host—becomes fascinating. Usually 230 is the law cited by platforms as the source for the argument “we can’t be liable for illegal stuff” but perhaps it has also given coverage for a strategy of not being liable for edgy but not illegal stuff.

This pressure functionally moves the “policy line” further to the right and enables them to capture more attention.

So if edgy content is so good at capturing our focus, why can’t media companies beat social companies at their own game? I mean, theoretically, the people who do this professionally should be better at finding the edge than amateurs!

In a traditional media company, everything that gets published had to be greenlit by a powerful central authority. Scarce resources had to be committed to it. This means the only content that gets published is the kind of content the powerful central authority is willing to put their name on—a mighty limiter in a world where executives don’t just seek wealth, but respect and status.

By eliminating the need for any commitment of scarce resources from a powerful central body, and by allowing content to be published without approval, UGC platforms were able to move the “policy line” far to the right, and attracted lots of attention. This isn’t the whole story of why open networks grew so fast, but it is an important and under-appreciated part of the story.

“Wait!” some of you might be thinking. “You’re telling me platforms beat publishers because they have a narrative that lets them evade accountability for the morality of the content published in their systems, but aren’t there plenty of shameless publishers willing to push the edge?” And you are right! There are lots of publications that have the explicit goal of being shameless or edgy (Barstool, Breitbart, and Vice come to mind immediately) but they still get consistently beaten in the war for attention by internet randos. Barstool has been forced to add in gambling products to achieve any significant revenue. Vice has pivoted to video (this definitely won’t work) and Breitbart has pivoted to nationalism.

Which brings us to the deeper reason why platforms have an advantage over publishers. None of this is necessarily new, but it is enlightening when interpreted through the lens of the content double bind. Platforms didn’t just win by avoiding accountability and moving the policy line, they also won by unleashing a powerful evolutionary force that can get far closer to the line than any media company could, because they get thousands of attempts.

Double Bind In Practice (Platform vs Publisher)

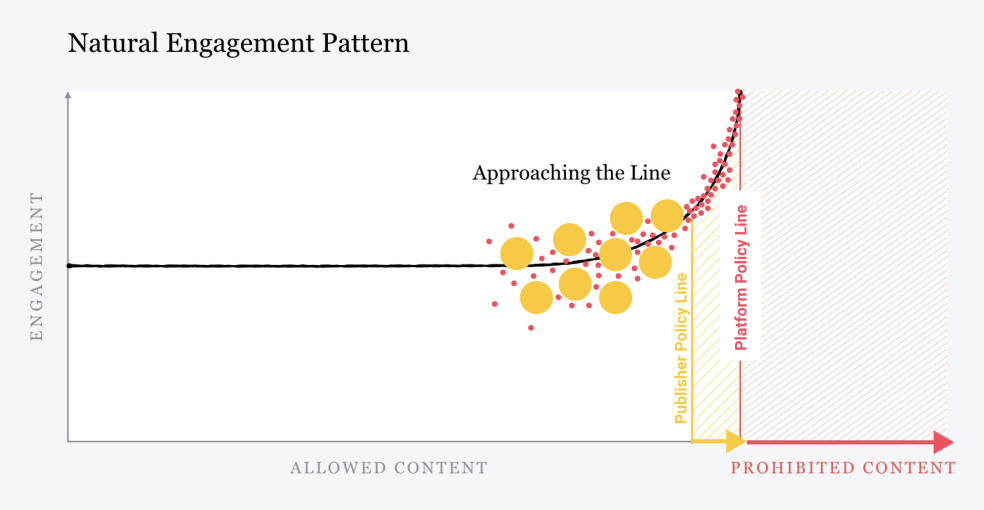

Algorithmically amplified content is an engagement optimization machine. If you are a stats person, it is sorta like an asymptote of an exponential function. To illustrate what I mean, let’s go through an example.

When a major news event occurs, there are essentially infinite ways to write about it. Length, flow, substance, style, all these variables can be combined to form a piece that will draw the maximum amount of engagement.

If you are a traditional media publisher, you have a limited supply of creators to make the content and an even smaller amount of places to display the piece to the consumer. The New York Times runs A/B tests on ~29% of their headlines, seeing which titles will get the most clicks. Even with this methodology, you are still only going to get a max of 5 or so chances to do the best you can. To add to the difficulty of being a traditional media publisher, you can really only target the content to a certain subset of the population. Different population segments enjoy different styles, further limiting the amount of engagement supply available.

To contrast all of these limitations, tech platforms have many orders of magnitude more chances to get the perfectly engaging content for each user. A tiny subset of people create content, most of them with little training or experience, and putting very little effort into it. When you have tens of millions of people doing this—including many professional individuals and media corporations— someone will hit on the perfect mix of style, voice, and length to go viral.

Red dots represent small amateur efforts, yellow dots represent large professional efforts.

But there is an even greater advantage to the platforms, not only is the creation process far more optimized then a traditional media company, but so is the targeting. They hold all the audiences, of all demographics, on their site, and can customize what individuals see based off of their personal viewing history. This has been to great financial benefit for ad targeting purposes but gives these companies the special bonus of content targeting too.

In sum, every single aspect of a typical media business’s process works better for a tech platform.

Again, you may protest, “But Evan, what about puppy videos? Or how the biggest individual writer on Substack is a history professor writing balanced takes?”

And you are right! Double-bind theory does not explain all the nuances of content or engagement. But it does help cast a light on the broad shape of the attention markets today. We are in an all out war for eyeballs, in every category of personal life and business. Truly great material can stand out from the sea of things beckoning for our focus. But edgy is easier to achieve than excellence.

If you have made the unfortunate choice to participate in this blood-bath of an industry, you essentially have two options. Create a process to consistently deliver truly incredible products or listen to the siren song of sensationalism. For most people, option two is easier.

A special thanks to my editor Nathan for his help on this piece. What I do wouldn’t be possible without his support.

💸 The Best Jobs at the Intersection of Tech and Finance

- Coinbase: Manager, Corporate Development (Atlanta)

- Qualtrics: Associate, Corporate Development (Seattle)

- JP Morgan Chase: Analyst, Equities Single Stock Derivatives (New York City)

- Salary Finance: Director, US Compliance (Remote)

You can browse more open roles on the Napkin Math Job Board.

Want to see your job in Napkin Math?

Since we launched two weeks ago the Napkin Math job board has delivered tens of qualified candidates for finance and strategy roles to some of the best companies in the world. Have a job you want to get in front of my 17k+ person audience? Post your job here:

Make sure to use the coupon code “Napkin Math 20% Off” at checkout to save 20%.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!