1

The question that’s always interested me most about HEY, the new controversy magnet / email service from Basecamp, is a very simple one:

Will it work?

I keep writing and shelving different versions of this article, because my attempts to answer the question keep getting thwarted by new developments. But now that the dust seems to have settled, we can take a step back and assess the situation.

Will it work? Almost certainly.

HEY’s founders’ stated goal is to attract 250k paying customers (~$25mm ARR), and it feels inevitable that they’ll get there. They’ve said the waiting list is already closing in on 200k, and apparently they’ve found a way to resolve their differences with Apple. So I’d wager a month from now they have ~50k paying customers (~25% conversion), and will be able to 5x that within a couple years.

But also, I think they could do way better.

HEY gets a lot right, but I think there’s a big flaw in their strategy: it looks like one product, but in reality it’s actually two different products (an email service, and an email client), which will resonate with two distinct but overlapping audiences.

Here’s the problem: Given their current product architecture, they’re only able to serve the intersection of those two audiences — the middle of the venn diagram. I suspect this artificially limits their addressable market by quite a lot.

I have a lot of respect for the HEY team, and of course I could be wrong, but I thought it’d be fun to throw this out as a hopefully-educational provocation :) I welcome debate and disagreement!

So let’s get to it.

2

HEY’s first product is an email service, and it has two primary growth loops. The first is the “@hey.com” email address their customers use, a nice viral mechanic. The second is a lot more interesting: controversy.

Specifically, HEY attracts attention from like-minded individuals by launching campaigns to move the overton window, and label previously accepted behavior as morally unacceptable. Whether you like this strategy or not depends on whether you agree with their moral stance.

Quite often the overton window really does need to be moved, and asking politely accomplishes nothing! But, on the other hand, people agitate and polarize communities over misguided policies all the time.

There are two controversies that have contributed the most to HEY’s growth. One was carefully planned, the other totally opportunistic:

- Their campaign against “spy pixels” — most people in the tech industry accept tracking pixels as a normal best practice, not a gross violation of privacy. HEY wants this to change, and “names and shames” senders who include trackers in their emails. (Including, notably, their biggest competitor, Superhuman.)

- Their feud with Apple — most developers accept Apple’s frustrating App Store policies. HEY wants this to change, and signaled they were willing to burn their business down in the hopes of starting a developer uprising. Eventually they agreed to a compromise that enabled them to stay in the App Store, but only after creating a remunerative fracas.

Notice how both of these issues exist on the edge of previously accepted behavior. That’s no accident!

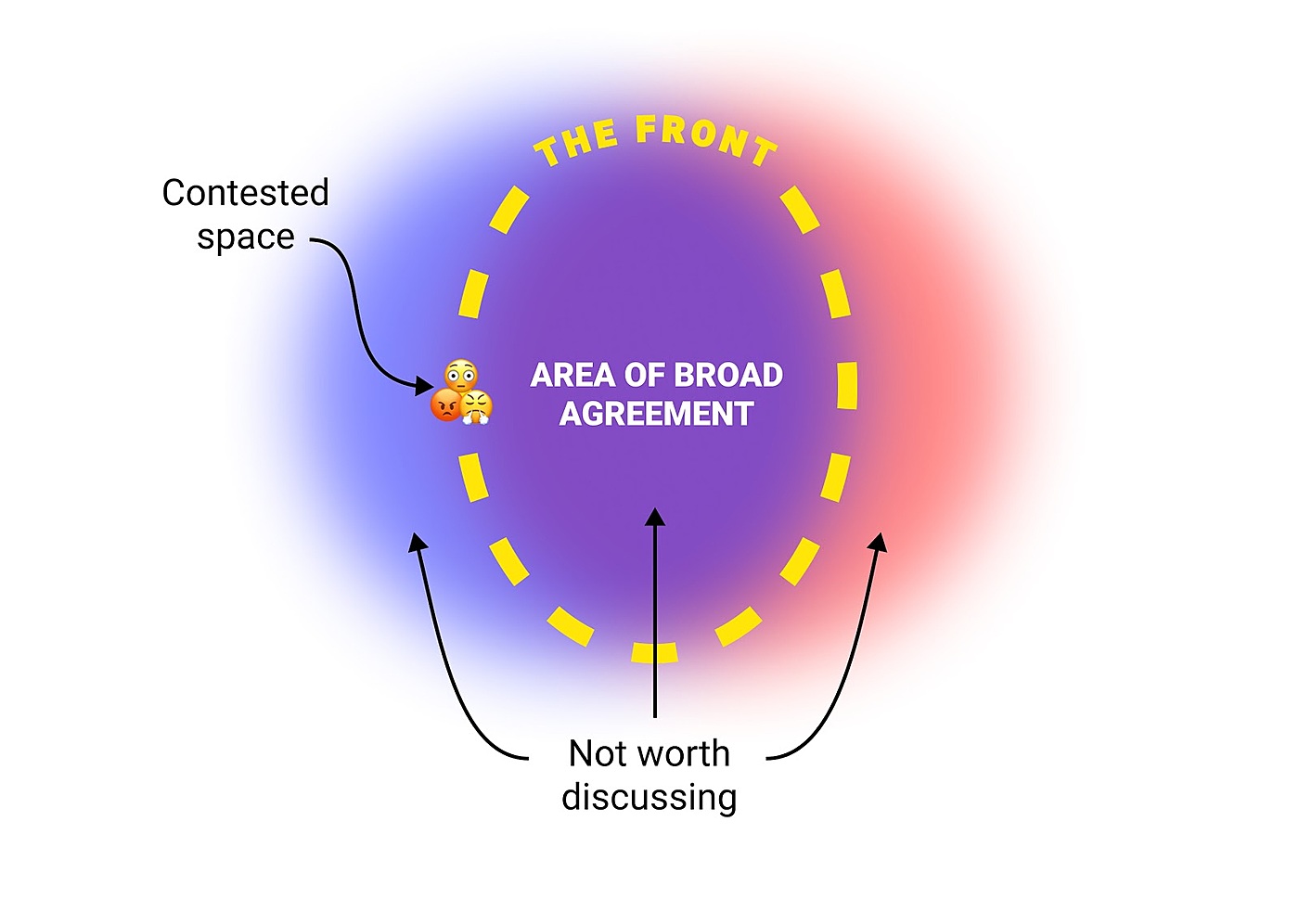

Operating on the front is the only way to use controversy to drive growth:

(Credit for this style of analysis goes to Slate Star Codex.)

Out on the front, some people think your idea is terrible, others think it’s obviously correct, and most people just aren’t sure what they think yet.

The collective attention of the internet hangs out around the front all the time, for three reasons:

- Power — Those on each side of the front rationally sense that it’s the most productive use of their energy. There really is an opportunity to change what is normal here. For example, look at Universal Basic Income. It works as a political issue in part because so many people haven’t figured it out yet.

- Identity — You don’t get many Catholic points for denouncing murder. Everyone agrees with you, so it costs you nothing, and therefore proves nothing about your devotion to Catholicism. Oppose condoms, on the other hand, and that’s really saying something. You only prove your devotion to a cause by sending a costly signal.

- Attention — The other thing about denouncing murder is that it’s boring. Everyone agrees. Controversy is a better way to get people talking. It creates a positive feedback loop where tribespeople on both sides are rewarded by their ingroup for taking a stand against the other. This is a powerful memetic strategy for replication and growth. And so, given the properties of this system, most of our attention revolves around controversial issues.

Some people think that HEY’s strategy is totally disingenuous, and that they’re only courting controversy to shill a product. But I don’t think that’s true. I think DHH and Jason Fried fully believe in the righteousness of their cause, and were truly willing to sacrifice some potential earnings in order to bring the internet more in line with their vision of how it should be.

But, also, you can’t deny it’s great for business! 🤷♂️

First, controversy captures the attention of like-minded people. It tells them what team HEY is on. Then, it imbues the act of using a hey.com email address with powerful meaning: “I care about my privacy and yours, I want the internet to be less dominated by the cabal of monopolists, and I’m willing to pay $99/year to help advance this cause.”

HEY could have quietly worked it out with Apple, the way every other developer does. But that would do nothing to draw attention to possible abuses of Apple’s power. And it would do nothing to drive signups for HEY.

The proof is in the pudding: When they launched they had a waitlist of 50k. Now, they’re nearing 200k.

That’s worth a lot.

3

So, what’s the problem with this strategy?

HEY isn’t just an email address that is private, secure, and outside the control of giant tech monopolies. It’s also an extremely opinionated email client with a lot of rough edges. Tying these two value propositions together destroys more value than it creates.

Some things are better off modular.

In my previous post on bundling I showed how in some circumstances you can create value by offering multiple products together. But it doesn’t always make sense, especially when bundling creates a worse experience for people who are more interested in one than the other (i.e. most people).

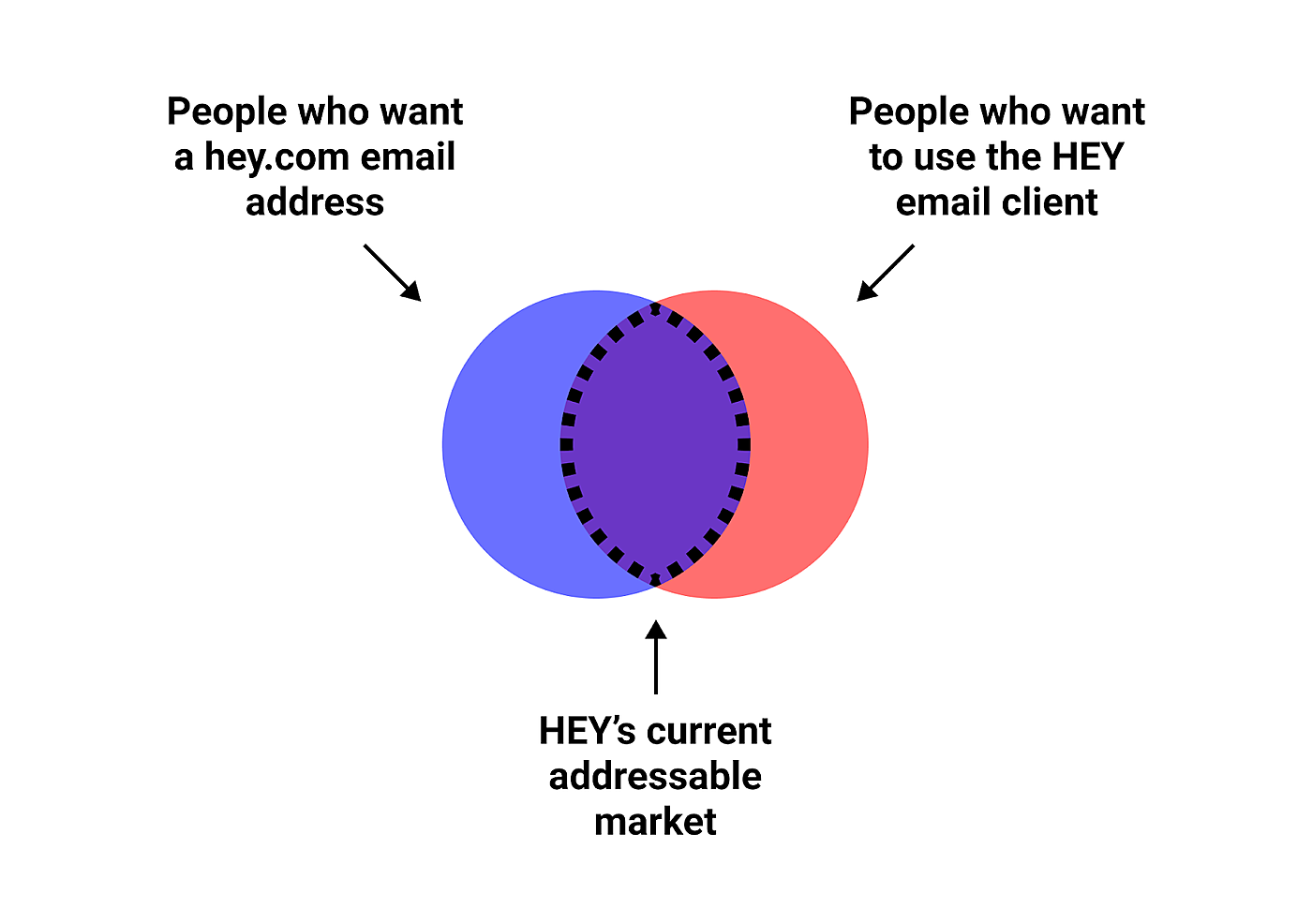

With HEY, there are two audiences that have some degree of overlap:

- People who value the HEY.com email address care about privacy, dislike tech monopolies, and want an email address that’s made by a trustworthy smaller business, and that lets everyone know where they stand.

- People who value the HEY email client want a radically different workflow for doing email, where new senders are screened out, there’s no such thing as inbox zero, and newsletters and receipts get sent to separate tabs.

HEY’s current product architecture is only able to serve the intersection of these two sets:

Why can’t they serve both? Because if you want to use HEY’s email service, you have to use the HEY email client, and vice-versa.

This is really different from the kind of bundling we do here at Everything, or that Spotify or Netflix does. When we add new writers to the bundle, subscribers get access to them, but we don’t force them to read it. It’s just an option.

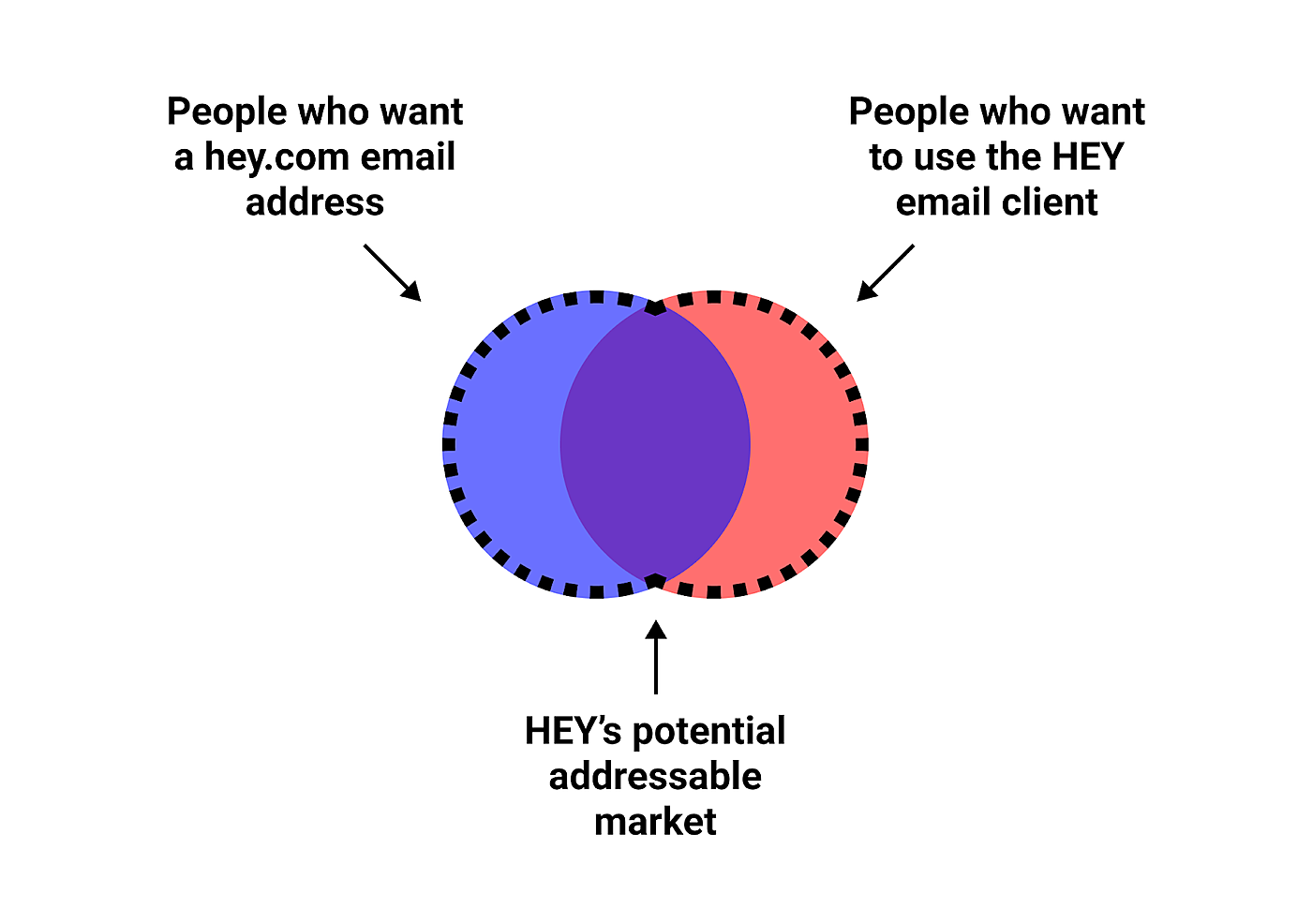

If HEY built an API or support for existing standards like POP/IMAP, and allowed any user to use a custom domain — or, if we’re really getting crazy, use their existing email service provider — then all of a sudden their market would grow to include the union of the two sets:

But obviously Jason Fried and DHH are no dummies. They are probably already aware of this. So why tie them together, and limit their market?

4

I can’t read their minds, but I can think of a few possible reasons:

First, maybe the only way to build the email client that people want was to also own the email service? Sometimes the only way to solve certain problems is to integrate multiple layers of the stack.

But I don’t think that’s the case here. I’ve racked my brain trying to figure out what HEY can uniquely do because they control the entire experience end-to-end, and I came up with nothing. I think you could make a HEY clone that works with Gmail and there wouldn’t be a single feature you couldn’t copy. (I’d love to learn about this if I’m wrong though! Please leave a comment if you know more than me about this.)

Second, maybe their philosophical objection to Google is so strong that they are totally willing to forego revenue in order to avoid depending on their Gmail platform? If you’ve read DHH’s writing on Big Tech, this seems extremely likely to be true.

But that’s just Gmail — why not work with IMAP/POP, so you can use the HEY email client with other like-minded email services, such as ProtonMail and Fastmail? I’d imagine there are engineering difficulties with supporting it, but I bet it’s possible.

Third, maybe this was their plan all along, and it just wasn’t in scope for version 1.

I think this is the most likely, actually. They’ve already said they plan on supporting custom domains, and I wouldn’t be that surprised if one day they ship IMAP/POP support so you can use a different email client. It would be more surprising if they let you use the HEY email client to manage a non-hey.com email address, but it’s not out of the realm of possibility.

But still, it raises the question: it’s hard to create a good email service, and doubly hard to also create a good email client.

If you only need to do one to be successful, why do both?

5

Here’s what I think:

HEY created both an email service and an email client not because they thought it would maximize revenue, but because it would be fun.

They had strong beliefs about how an email client should work, and so they built it. They had strong beliefs about how an email service should work, so they built that too. It’s a creative outlet. “A love letter to email,” they said.

Speaking as an engineer, I can tell you that messing around with IMAP/POP is not very fun. You’d get bogged down debugging little problems for ProtonMail users all the time, instead of building fun new features. It’s a lot more fun to control the whole thing end-to-end.

And because Basecamp is already financially successful, and HEY has attracted so much attention from like-minded consumers, they’re almost certainly going to be able to recoup their investment and earn a tidy profit.

That’s the benefit of not having venture capitalists on your cap table. You can decide to do things just for fun. You don’t have to optimize for growth.

What a concept! 🤯

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!