TL;DR

- Pricing is much more complex than simply picking a numerical price. It involves a complex overlap of finance, go-to-market strategy, and product decisions.

- Getting access to rich user data gives technology companies the ability to price more accurately than any other industry.

- Pricing strategy is really product strategy in technology. Non-tech companies are playing with financial levers, technology companies are playing with product ones.

- Accurate pricing is determined by quantifying the value of the problem your product is solving, capturing as much of that value as you can, and then charging in a manner that aligns you with customer growth.

Perhaps the most difficult question to answer as a business owner is how much to charge for your product. Too high and you’ll have too few customers, limiting your growth. Too low and you’ll leave too much money on the table, keeping your company in a cashless, anemic state. Historically, people had to just kinda...pick something. Even if the product was selling well, they would have no idea how people actually felt about the product/price. Was the utility they received from the product matched by what they paid for it?

However, there is an elect group of businesses that get much more granular data then that - technology companies. By being able to monitor the “who, what, when, where, and how” of customers using their product, they have the ability to price much more accurately than businesses without this privilege. To get a sense of how big an impact technology makes on pricing, just imagine if Nike not only knew what shoes you had bought, but understood the conditions under which you used them. Are you throwing on some runners to head to Starbucks? Or are you using them in hardcore marathon prep? In this hypothetical world, what if they could upcharge you on a rainy day for “Mud Mode” to make your shoes stick? This kind of pricing superpower is a major reason why technology businesses tend to be worth so much more than analog businesses.

The thing is, you don’t get this benefit automatically by being a technology business. All the technology does is increase your degrees of freedom. It gives you more options, but it’s still on you to choose a good one. And it’s far from a given that you’re anywhere near optimal pricing territory. If you run a technology business, there’s a good chance you picked something simple in the early days and stuck with it because it seemed like a pain in the ass to change. It might be worth re-thinking.

Today I want to talk about the 3 types of pricing strategies that exist. Afterward, I’ll go into more depth about how these strategies are implemented by leading technology companies. The majority of case studies will draw from business-to-business (B2B) software. This might seem weird if you’re building a consumer company, but enterprise software is perhaps the most developed market vertical that utilizes the advanced pricing models, and frankly, it’s what I know best :).

Understanding what to charge

There is maybe no more terrifying thing than going to your customer and saying, “ You need to pay us more this year.” Perhaps because of this, most people default to the quickest method of deciding pricing.

The easiest of the three pricing models is cost-plus pricing. It’s super simple: figure out the cost of delivering a service and then charge a targeted profit margin above it. So if your product costs $1000 dollars to deliver and you had a gross margin target of 20% then you simply charge $1200. The algorithm is PRODUCT x (1+ %GROSS MARGIN TARGET).

This method is often decried by internet thoughtbois, who are quick to remind you that one must always “pRiCe BaSEd On ValUE, NoT On COsT”. I’m not so sure this is the case. When you think about pricing, the natural tendency is towards revenue maximization for the product you are selling. However, pricing is a strategic choice, not solely a revenue one. By pricing some products at the absolute lowest you can sustain (or even pricing it below what you can do in the long-term) cost-plus pricing can allow you to gain market share. Many Software as a Service (SaaS) companies will price their services arms (where they help customers use their product for a fee) at the absolute minimum if it unlocks additional software revenue. If you are looking for a more in-depth case study of that choice, check out my case study on Workday (Paying subscribers only).

But the problem with cost-plus pricing, especially when seeking to maximize profit margins, is it’s often hard to tell how much “plus” you can get away with. More is better, but at a certain point, nobody will buy. So how do you decide? This leads us to the next model...

The second easiest model is competitive pricing. Again, fairly simple, just go to your competitors’ websites, see what they are charging, and set your pricing accordingly. This is really only a good pricing strategy for those in established markets. If you are the 945th startup who is making a note-taking app, then you can just copy what your competitors are doing. If you are doing some completely novel, with no real competition this strategy isn’t for you. There is no specific formula for this method.

Note: Transparently, this is the exact method I used when thinking about Napkin Math’s pricing. The newsletter is $20 a month which puts it about in the middle for other publications discussing finance and technology. However, I actually think I’m undercutting all the other newsletters out there! (My apologies to my brothers and sisters of the pen). When you subscribe to NM, you also get access to all the incredible writers in the Every bundle who cover topics like business strategy, productivity, and internet culture. Plus you get the moral high that comes from helping me pay rent, which IMO should be an even sweeter reward.

The final method is the one I usually recommend. This is value-based pricing. There are a variety of definitions online about it, but I define it as, “The pricing methodology that is driven by how much a specific customer segment believes the product to be worth.” Value-based pricing is totally separated from the COGS of a product or the actual monetary value of what the product does. Instead, it is how valuable a specific customer perceives it to be. For example, I think anyone who buys a Gucci $495 t-shirt is being silly. It is just a shirt! However, many, many consumers disagree with me and perceive the value of that flimsy piece of cotton to be at least $495. The reason Gucci can get away with this highway robbery is that they are very good at identifying the customer segment for this product. When you are conducting a pricing analysis, segmenting your potential customers based on what they value is just as important as the actual price itself.

As an example of this methodology (I warn you, this is truly stupid) let’s assume you are selling the world’s most fantastic toilet in the frigid north of Canada. It heats your butt, it never clogs, it makes your poop smell like chocolate chip cookies, it does your taxes, and it can even save your marriage. Note: I told you this example was stupid. You chose to read this. Unfortunately for you, a Japanese conglomerate also has incredibly advanced toilet technology and has released a competing product with almost all the same features at $999. This magical toilet can do the cookie thing, it's better than TurboTax, etc, etc. The only thing it can’t do is have a heated seat. The temptation here would be to do a value analysis for each individual feature. You would hire Qualtrics (and get ripped off in the process) to do a conjoint analysis asking customers such questions as, “How important is your marriage? Why would you want it to be saved in an outhouse?”

This would be the incorrect choice. The only question you actually need to ask is, “How important to you is a heated seat?” You would discover that to Canadian consumers, having a heated seat is super important! It is very cold up there. A warmed nether region is worth $500 bucks in addition to $1000 bucks in value of all the other features. This would enable you to charge $1500 versus your competitor but only in Canada. You would need to do this math again if you tried to sell your product in other, less frozen, regions.

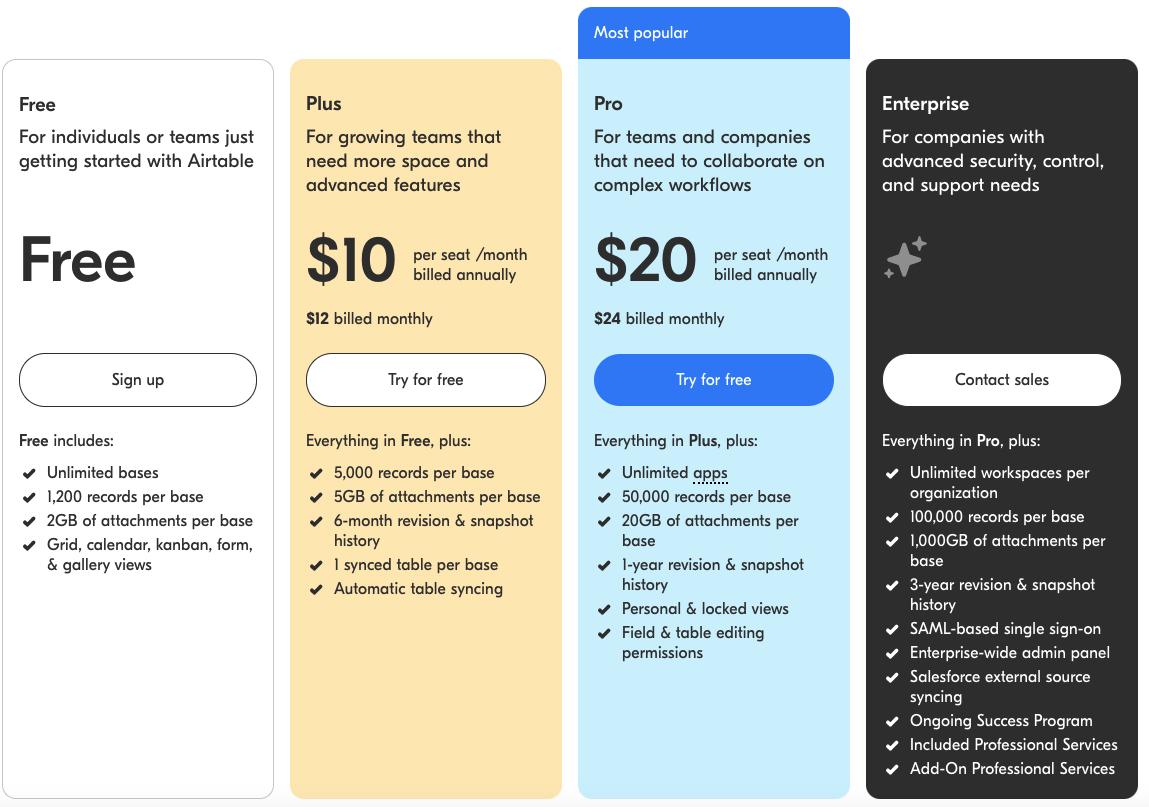

When you undergo the work of figuring out which customer segments value which features, you can tier them based on who values what. An alternative and maybe easier way of saying this is how your price is set by how valuable is the problem you are solving for the customer. Let’s look at an example with Airtable’s pricing (a Microsoft Excel competitor).

They clearly have done a lot of pricing work segmenting out how the product would be used. This is even better than a simple survey - by tracking what product behavior patterns are among their user base, they are able to tier things off of what matters. As an example, their enterprise plans (which from what I hear from my data engineer friends is 3x+ the price of their Pro Tier) have single sign-on. This is where you click “Sign in With Google” or Okta or whatever and it logs you in sans password. This is actually a super important feature! Single sign-on really tightens up enterprise security and is an absolute necessity for any company with a half-decent security standard. Enterprise clients will almost certainly be forced to have this upgrade. Security is one of those things that have very nebulous value so there is an additional opportunity for pricing arbitrage. Airtable understood what value was important to what customers and used that as an opportunity for increased pricing.

Understanding how to charge

So let’s say you have done the work to understand what is important to users. There are beautiful charts presented that clearly link features to value. The only question is - what do you do now? There are three basic options:

Licensed, Universal Use (Old, Decrepit School Method)

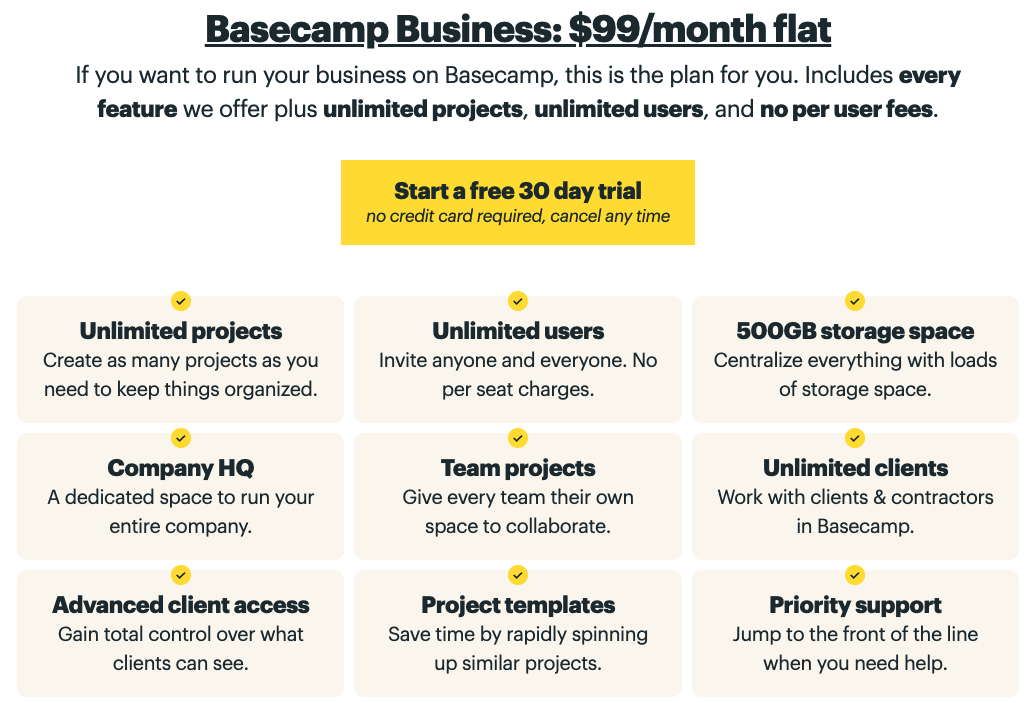

We start with the easiest method to implement. You simply charge customers a single flat rate irrespective of usage volume, features required, or number of end users. The arguments in favor of this strategy are speed and simplicity. It is obvious to customers what you charge and it allows you to focus on other things. Of course, there are numerous downsides. By setting a single price, you’ll have no choice but to acquire new customers to grow your revenue. Other pricing models align your customer’s growth with your own so you can capture more revenue over time. (I’ll have a post on this strategy in the next few weeks). Additionally, there is no stratification among customers. 5 or 500 users, customers pay the same amount.

- Software Example: Frankly, this is such a minority of examples the only successful example I could find was Basecamp. This company is notoriously *coughs* opinionated so I feel comfortable offering an opinion on their pricing. While this works for them, it is likely they are leaving a ton of money on the table with existing customers.

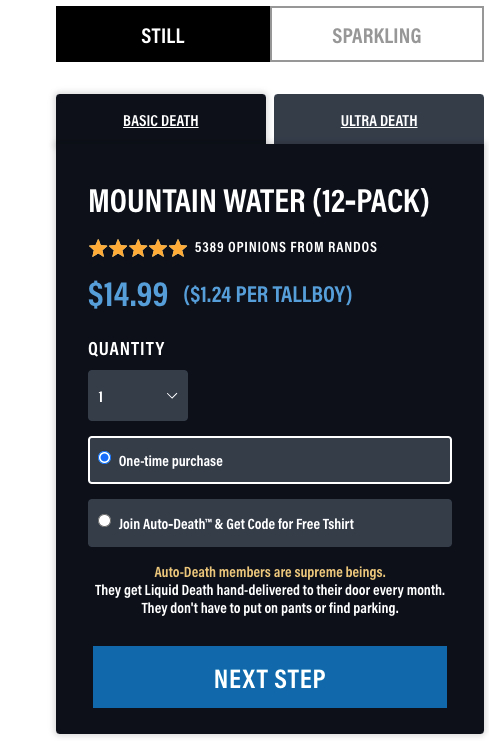

- Non-Software Use Case: This is basically every business you can think of! All consumables with some limited lifespan essentially operate on a limited license model. An interesting and somewhat adjacent comparable in e-commerce brands selling food products. Nearly universally they all show the price to buy it online. But they all try to nudge you towards a subscription. You still get the exact same product (sometimes with an added discount) but now the company is better able to forecast what you will do and can plan accordingly. Liquid Death is a water brand that has great marketing and has a pricing page that does exactly as I described above.

Per-User (Proven Workhorse Method)

The first-ever pure-play software company was the Computer Usage Company in 1955. Software was so new back then that they were essentially a custom software development house for their customers. They made retail inventory systems, election tally systems for IBM, and numerous technical applications for places like NASA (source (you should read this if you have a spare 15 minutes—it is a fascinating history)). Consulting is a tough business to scale and grow, so in the 1960s companies like IBM started offering centralized licensing where companies could pay for access to specialized programs. Delivering and maintaining the software would generally require someone onsite. By being onsite and monitoring software usage, the companies started to have more sophisticated pricing enabled by customer data. It wasn’t until the internet enabled cloud-based software the purest form of Software as a Service was born. The era of pure-play SaaS was truly ushered in by Salesforce’s $CRM IPO in 2004. For the first time, you could have minute details about each customer and truly build targeted pricing.

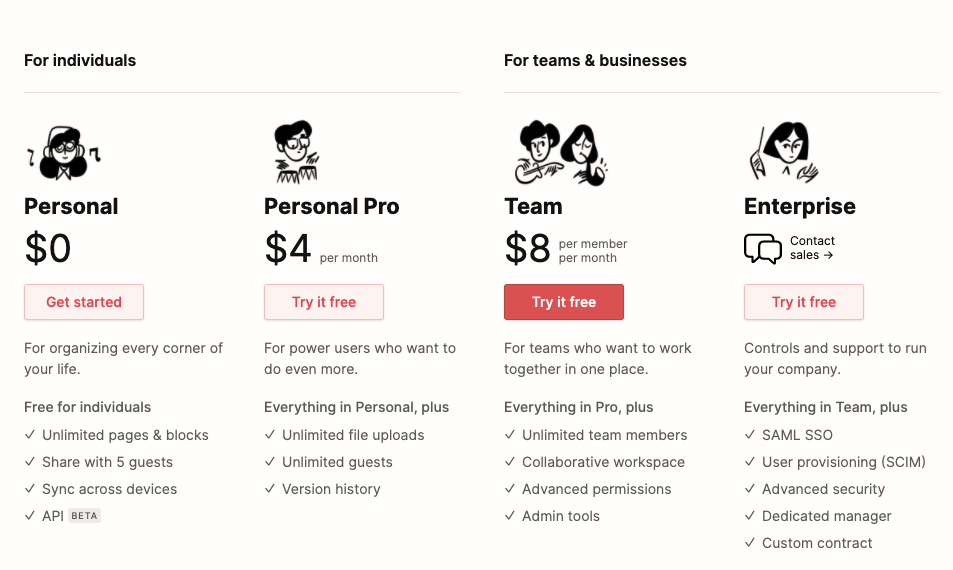

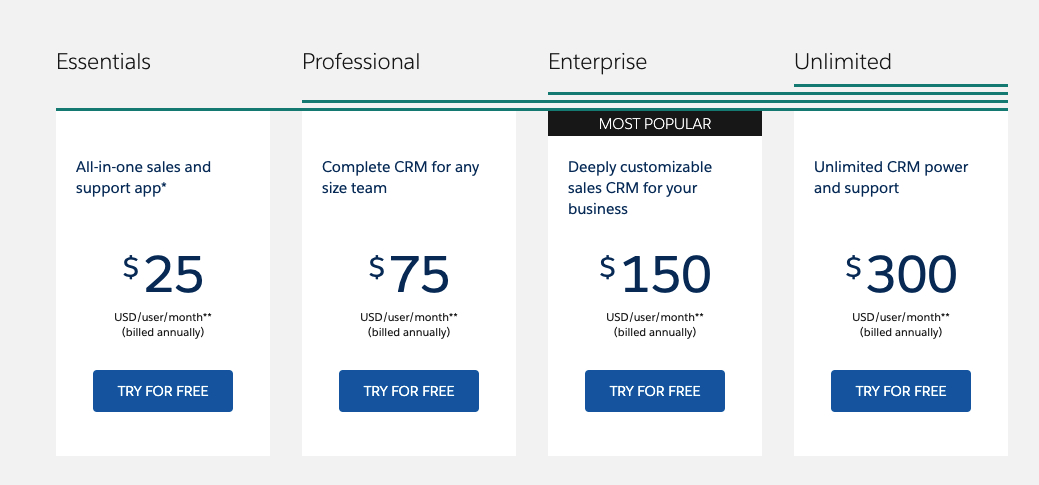

The method decided on by almost all companies was per User pricing. This is where a company would take on a subscription that gave a user access to a number of features. You can then tier access. If you’ve bought software at any point in the last 15 years, you will know what I’m talking about. For example, here is Notion’s pricing page:

Salesforce:

- Software Example: This is pretty much...every software company. It is a well-understood pricing plan by customers, allows for more targeted pricing, and does a great job at capturing additional upside in comparison with the historical licensing model. It isn’t perfect but it works great!

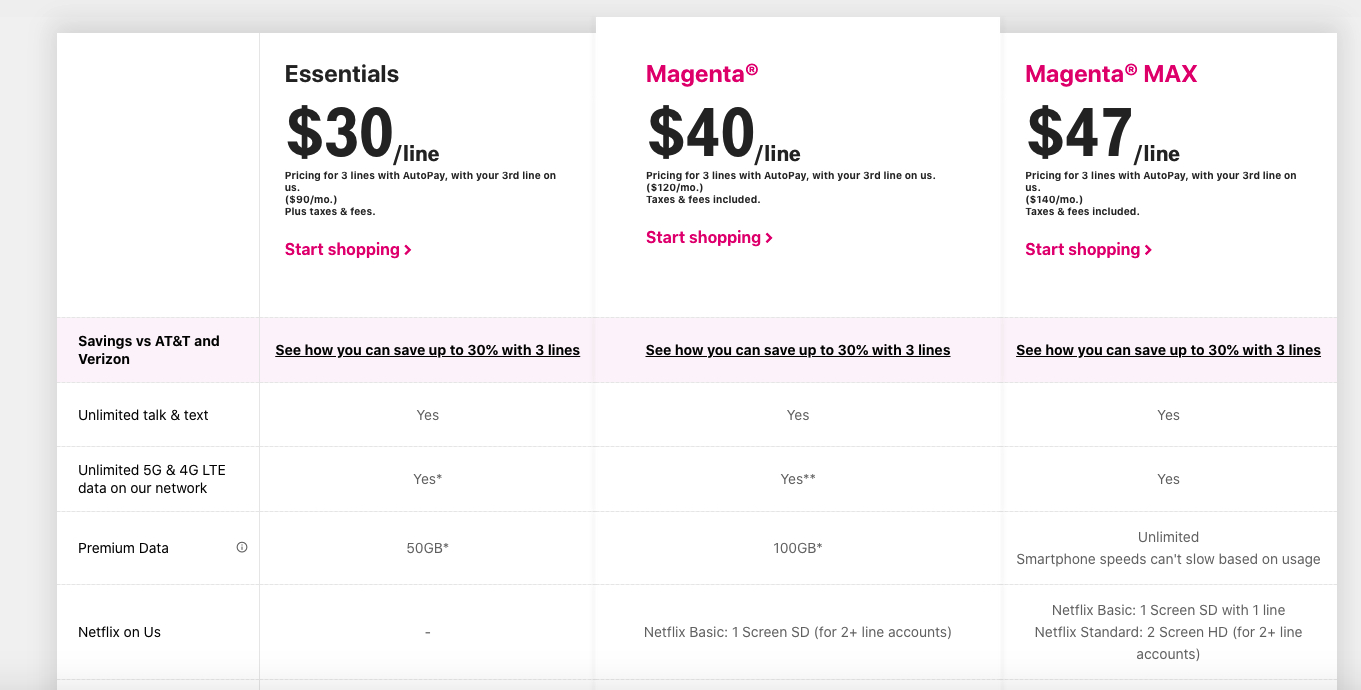

- Non-software use case: Pricing stratification done by customer use case is incredibly powerful even outside of B2B software. One of my favorite examples is Phone Plan providers. Universally, they will have a per-user pricing based around volume/use case. Below is a screenshot of T-Mobile’s pricing page.

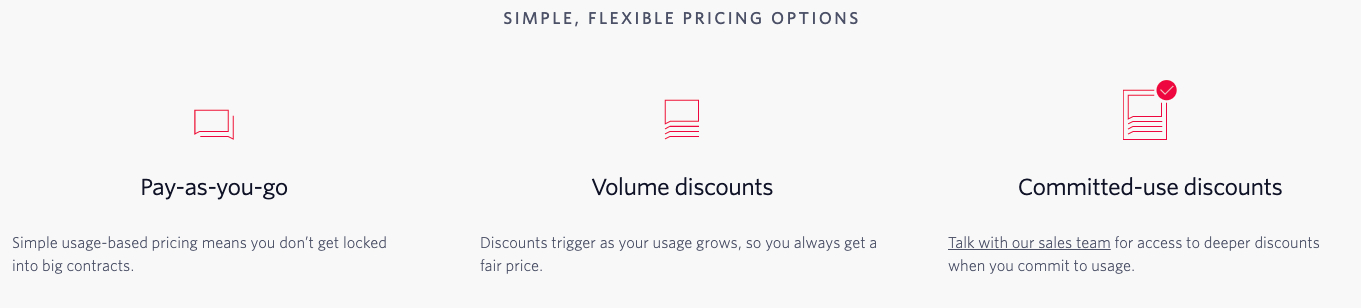

Usage-Based (New Hotness Method)

When you are doing per-user pricing, you are still slightly disconnected from your customer’s growth. If you are just trying to sell a few seats, then it isn’t a big deal. But if you are selling a product that is necessary for the growth of a business, a per-user pricing can mean you are viewed as a headcount cost center. If (and this is a big if) you help deliver a major portion of your customer’s success, you can charge usage based pricing. This is where you charge for each time your product is used *duh*. This model has seen more uptick over the last few years with tech darling Snowflake most prominently showing the framework’s promise.

- Software Example: Twilio was one of the first public software companies that demonstrated how well this could work. They offer an API that allows engineers to easily communicate with their customers via texts or emails. Intuitively, this makes sense! Sending a text message isn’t free and customers easily grok pricing based on how many texts are sent. At first glance, this feels a little like cost plus pricing. And you would be right! I’m sure Twilio has an optimization algorithm around usage, revenue volume, and margin. However, this is a more sophisticated choice than just forcing a margin target on a product. By Twilio pricing texts at a minimum, they encourage adoption of additional, higher margin products like Segment. This model has taken them from a $15 share price at their IPO in 2016 to a $389 price as of July 7th. I don’t pretend to be a public stock pro, but I'm pretty sure a 2,493% increase over 5 years is considered good. So at least for them, this model works well.

- Non-software use case: StitchFix is perhaps the closest parallel from non-software that utilizes usage-based pricing. For the uninitiated, StitchFix is a clothing e-commerce company that ships you a box of clothing based on your interests. You keep what you are interested in and send back the rest. From there you can periodically (say once a month) receive a fresh box with clothing for you to try on. You keep what you use and don’t pay anything else. While this isn’t quite recurring revenue (in-depth explainer on the concept for subscription revenue for paying subscribers of Napkin Math) it feels pretty close. By taking note of what clothes you keep, they are building the usage data so beloved by software companies.

What model is best?

To be clear, there are a thousand more permutations of the pricing strategies I’ve described above. You can do total employees, API calls, feature pricing, all sorts of stuff. What I’ve tried to capture with the 3 options above is the spirit of strategy not the letter of it. The point of this article is that technology has enabled near-infinite ways to measure how your customer is using your product. Using this data you can obviously shape your product roadmap (wow everyone sure seems to like x feature, let’s double down) but it has an equal effect on your pricing strategy too. The classical error of Silicon Valley is in assuming you can just build the tech and customers will come. The error outside of California is that if you price it right the customers will come. Instead, it is in the difficult act of melding the two camps that you will find an optimal route to success. If you have questions for your own company on how to think about pricing, DM on Twitter, I’m always happy to chat.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.08.31_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!