Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

Reckoning with the legacy of Bill Gates in 2024 requires engaging in a gut-churning calculation: Do his multiple dinner meetings and single late-night hangout with Jeffrey Epstein, combined with a flight on the convicted sex offender’s plane, discount the tens of millions of lives he has impacted through his philanthropic work?

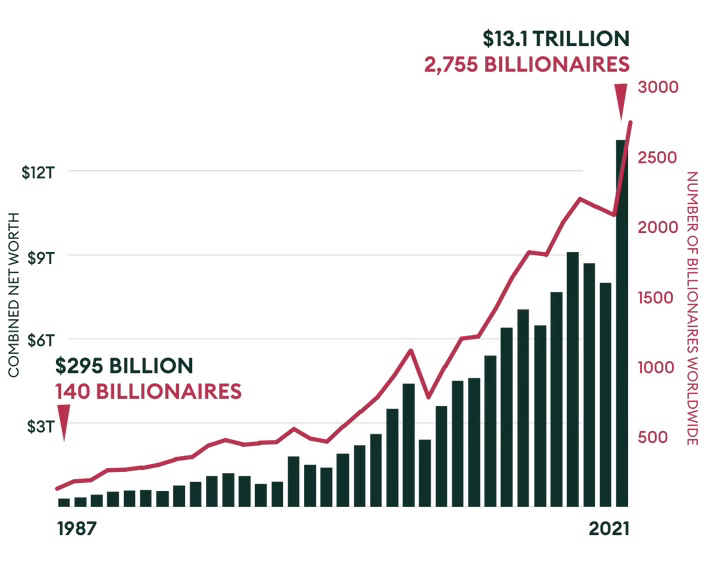

Yes, this math is reductive. And yes, it is almost certainly unfair. However, that does not mean it isn’t a worthy question. Billionaires are more numerous and powerful in our society than ever before. The world was home to 140 billionaires in 1987. There are 2,755 of them today.

Source: Forbes.Beyond their sheer fiscal might, the power of the B-class lies in the services they control and the influence those services have on us plebeians. Their attitudes and philosophies shape the internet gardens in which all of us roam. Exhibit A: How Elon Musk has adjusted the moderation policies on X to be more in line with his views on free speech, or at least the kind of speech he prefers.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.08.31_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!