Sponsored By: Brilliant

Worried about AI stealing your job? Stay one step ahead with Brilliant's bite-sized interactive lessons.

It sure does feel like the media industry is having a moment. The moment is a funeral, but still, you know, that is a moment. Vice has swung from a $5.7B valuation to declaring bankruptcy. Buzzfeed shut down its news division and is doing layoffs. Disney laid off 7K employees, News Corp, 1,250.

Despite the setbacks, I still love the industry. On the high end, there are some companies that have done exceptionally well, such as the NFL, a24, The New York Times, and Netflix. Closer to home, I find inspiration in successful micro-publishers like Ben Thompson or other newsletters on Substack making millions with one or two employees.

So what gives? How can this industry that is so lucrative for a few be terrible for so many?

To understand why, I’ve talked with dozens of media industry participants. Over coffee in Brooklyn, Zoom calls in Australia, and bars serving drinks somehow infused with mushrooms in San Francisco, I’ve chatted with everyone from media investors managing $1B+ funds to small digital publishers with less than a thousand subscribers. I’ve thought and read and analyzed for months to try to synthesize what everyone is telling me. Today’s post is the result of that work.

The TL;DR is this: Consumers don’t want to pay you, Facebook is better at advertising, and unique distribution is necessary for long-term survival but almost impossible to get. If you somehow get an audience, congrats! Your reward is a million competitors who are constantly trying to kill you and steal your audience. Still, if you are able to climb up the power law, you may be able to build long-term success.

In honor of my recently laid-off writer comrades, I have structured my arguments into a Buzzfeed style list:

1) Media companies are always the shit eater of consumer tech

Over the past 10 years of building, a media company has been subject to the following technological shifts: newsfeed pivots, the depreciation of cookies, Apple’s App Tracking Transparency policy, platform-specific article formats, Web3, long-form video, the rise of TikTok, and now, GenerativeAI. Each and every one of these trends merits a reinvention of a media business, but most importantly, a media company didn’t invent or control any of these. All of these were enabled by science but implemented by big tech.

The best time to level up on AI was yesterday. The second best time? Right now.

Brilliant is the best way to level up on cutting-edge technology like AI, neural networks, and more. With thousands of hands-on lessons packed with interactive problem-solving, Brilliant lets you learn by doing—so concepts really click. Plus, since we know you're busy, each lesson takes only minutes and can be done anytime, anywhere.

Get an edge on tomorrow's highest-paying jobs and start your 30-day free trial today.

For every single evolution of technology since the internet, content creation companies have been moved to the role of commodity supplier. As technology changes the types of popular supply, a media company is forced to alter its product or be left in the dust. To be a media company is to never be in control of your distribution and to be subject to the winds of progress on a daily basis.

2) The internet broke media businesses, not social platforms

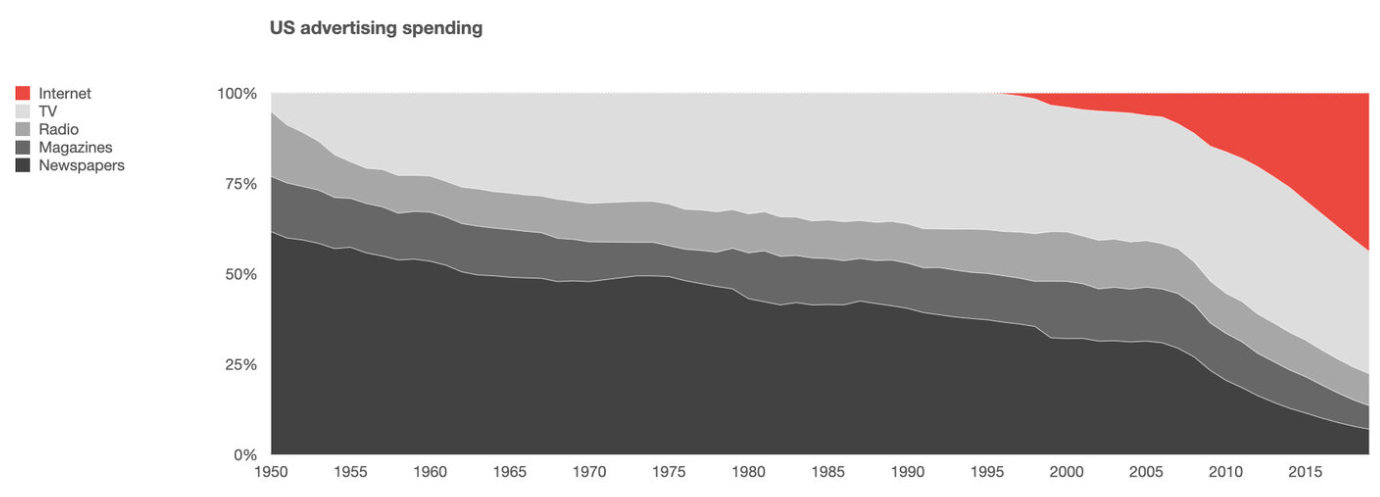

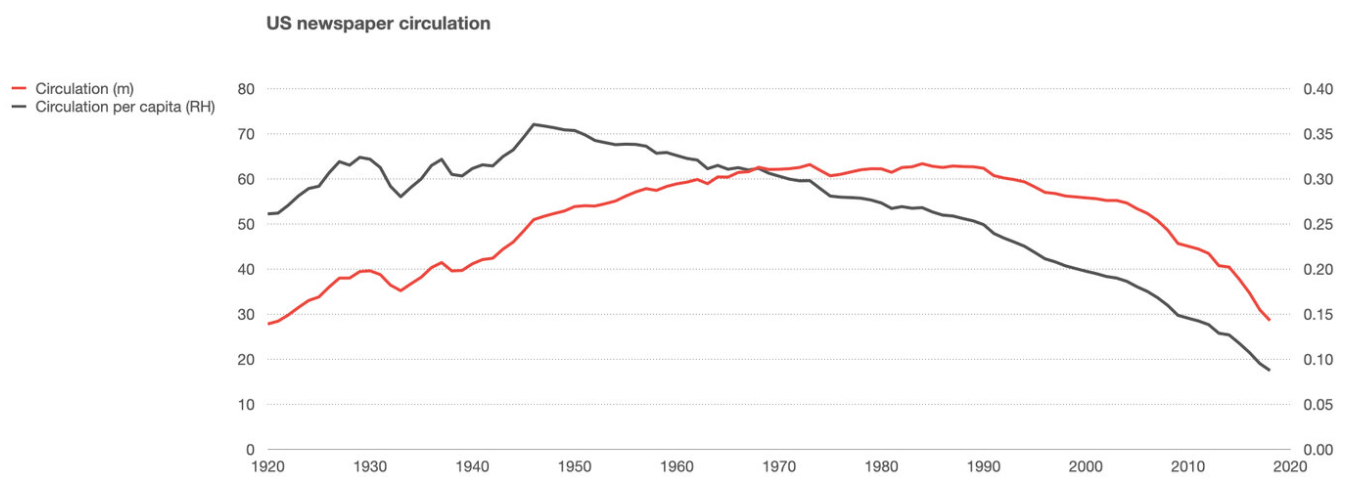

Prior to the internet, both content creation and distribution were limited. The physical costs of production/distribution were too much—printing presses, TV studio cameras—and required upfront capital. There were a limited number of content creators and a limited number of distributors. At every step of the process, there were powerful, profit-extracting gatekeepers. From the 1920s to 1940s, newspapers and radio were essentially the only content game in town. They had powerful regional monopolies, exclusive reporting, and a stranglehold on local advertising. The past 80 years has seen more and more distributors and content creators come along. The newspaper industry’s revenue collapsed:

It also happened on a distribution per capita—newspaper circulation have been declining since 1950.

I know it is tempting to blame our lizard people overlords (looking at you, Elon) for the media's struggles, but that isn’t the case. Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube are just manifestations of the power of infinite, global, and free distribution that the internet provides. Plus, newspapers began to decline far before that.

Some content distribution rails are better than others (which is why we post these essays on our own site and distribute it through email), but the internet is the root of the problem. Major technology shifts take a long time to permeate through society, and we are still very much in the early stages of the internet. Shoot, cloud software, which is much more obvious to scale/spend has been around since 1999, and is still only 15% of IT spend. Information technology is still on a multi-decade journey and media companies are just along for the ride.

3) Customers have the mental focus of a goldfish

Whenever I visit San Francisco and tell people I’m a writer, some engineer who thinks they know how to do my job says, “I just want good, in-depth writing, with a nuanced take.” Cute but wrong. This is not what people want. People want porn, celebrities, gossip, puns, puzzles, and opinions that agree with their heuristics. I promise you, in the name of all that is holy, the more pictures that I put in my piece, the better the essay performs. And my audience is pretty exclusively engineers, founders, and investors! Y’all are supposed to be the analytical people.

People’s revealed preferences are always for fast and entertaining and a dopamine drip line connected directly to their cortex. This means that a media company’s competitive set is essentially everything people look at—it isn’t as simple as the category of content you create. My job as a writer is to write a product more compelling than what the TikTok algorithm can surface.

Different forms of content will solve different jobs for people (I don’t expect the WSJ to give me the same utility as Buzzfeed), but when someone opens up their web browser, they have to make that choice every time. The default lizard brain is almost always more likely to win.

Now to be fair, a few media companies have found audiences that appreciate long-form, complex content. It's just that the biggest common denominator is that while some people perform long-form, everyone likes fun, easy stuff. There is a reason why James Patterson and romance novels are consistently among the best sellers at Barnes and Noble. People like brain candy! And even if you fully embrace mind sugar, that doesn’t solve the problem of being a media business. Buzzfeed optimized its content that way but can’t get the revenue-to-cost ratio right.

4) Media companies revenue scales exceptionally poorly

Facebook’s ARPU for North American users is roughly 200 bucks a year. The New York Times, the world’s most successful legacy media company, is about $40. The best-in-class subscription media company, Netflix, has an average revenue per membership that is at least $100 per year depending on how you slice it. Even for Facebook, this really isn’t all that much money in the world of technology! In entrepreneurship, a dispassionate founder is looking to make the most money with the least amount of risk/effort possible. Media is a really bad way to accomplish that! Subscriptions will typically see a monthly churn in the range of 1–5% a month for the first year, meaning you are forced to continually pump that top of the funnel to keep the business alive. You very clearly can make lots of money with these sorts of ARPUs and LTV/CAC ratios, but it is really hard to do from scratch.

On a risk- and ARPU-adjusted basis, starting a SaaS company is a better bet every day of the week. Even the wonderful businesses in media still have a low ARPU.

5) Monetize with subscriptions? No one, and I mean no one, wants to pay

When I was growing up, there was always an ad during reruns of Law and Order SVU about how I could save a kid's life in Africa for the cost of “less than a cup of coffee.” Those charities couldn’t even get people to give them a couple of bucks. And if people aren’t going to save the life of a child for a few dollars, they certainly aren’t going to pay the rent of a Brooklyn-based writer who only drinks organic fair trade.

It is incredibly difficult to get people to pay for media products. Consumers have high-demand elasticity, meaning that if you get too expensive or publish a few posts they don’t like, they will simply swap you out for other content. A best-in-class conversion rate from free email subscribers to paid is 5–7%. That is very, very hard to do. If you push it past that point, it means your free list isn’t growing fast enough.

Like I mentioned earlier, subscriptions can work. After all, this very publication is only possible because of your support. Note: Thank you! However, it only works for a very, very small percentage of creators. For example, on Twitch, only 0.06% of streamers received over the U.S. median household income of $67,521. Every other data point I’ve ever seen in the creator economy holds this power law distribution to be true. To monetize at scale with subscriptions, you have to have a massive top of funnel and a best-in-class conversion ratio.

6) The ads suck and no one wants to buy them

A media company can drive additional ad revenue by increasing three things: the number of viewers, the number of ads, the price/performance of ads. The most important variable, by far, is the price/performance variable. Being able to target ads based on intent and interest is the holy grail. If you go for mass scale (which is the entire point of keeping your product free), then you’ll need to be able to do additional targeting/enrichment on customers’ data. However, because no media company is where the transaction data and demographic data live, it is unable to do proper attribution/targeting. I’ve written in the past how Twitter and Snapchat are probably screwed for the exact same reason. And if those folks, with hundreds of millions of users and far more demographic data, can’t do it, ye old internet publication will be awful at it.

This leaves media companies two very ugly choices. You either go after a niche, high-value audience that big platforms struggle to capture (the Every approach). Or you do mostly brand ads where specific performance isn’t as important (the Axios approach). In both cases, you have to spin up your own salesforce, sell the ad slots, get the copy approved, on and on. It is a miserable process. In both cases, it is a worse ad product for marketers versus the infinitely scalable and easy to use ad platforms like Amazon or Google. The big tech platforms offer better products in basically every way for marketers to use.

7) Your employees will be able to tell you, in perfectly written prose, why you suck

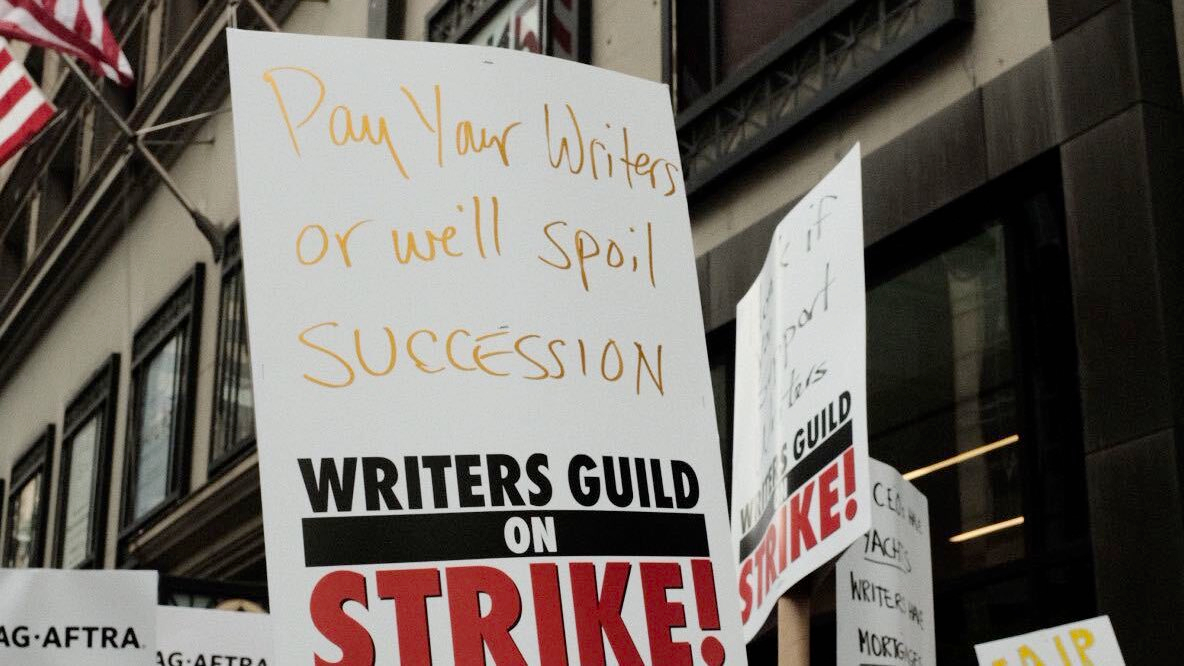

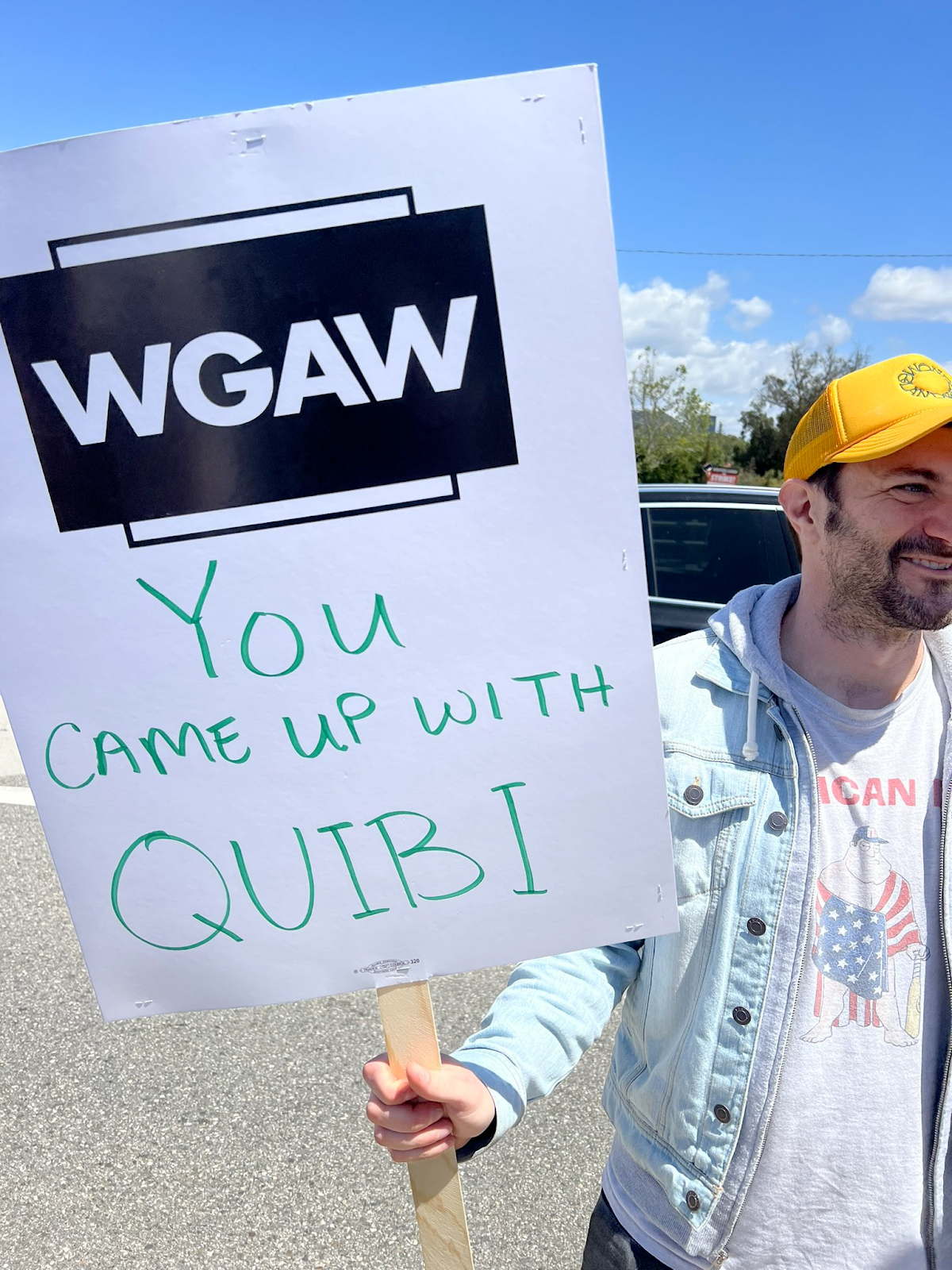

Look, I am in favor of labor empowerment, but it is exponentially more difficult to manage a workforce that is able to easily broadcast their displeasure. It is worse when their skill set lends itself to exceptionally viral content. For example, look at the picket signs from the ongoing writers strike:

And for my readers who enjoy startup history…

These are funny! And terrible for management!

As a founder, what you want is a workforce who has absolutely no power over you that you still choose to treat very generously. Media appears to be in the opposite situation. All the staff have big platforms and their bosses treat them worse for it. Note: Every is way cooler than that—in my second post here, I published my contract and a model I built to determine if I was getting ripped off.

So, I've spent the last 2,000 words explaining why media is a horrible business. But I still love it dearly—and there are examples of truly great media businesses.

Leveraged individuals

For instruction on the future, I think we can look to the past:

The first 10 films of Pixar are an artistic and economic achievement unlike anything seen in the history of capitalism. Before its first film, Toy Story, Pixar was making advertisements. But with the release of the John Lasseter–directed film, the company went on a truly legendary run. That span included The Incredibles, Monsters, Inc., Up, Finding Nemo, Ratatouille, and five other all-time great animated films. These movies pushed the boundaries of storytelling and technology, touching people the world over. Simultaneously, Pixar achieved financial success; its films had a gross profit margin that was nearly 4x every other movie released during that time.

Hamilton Helmer argues that the key to Pixar’s success during this period was a “cornered resource.” Specifically, it was a brain trust of hyper-empowered early employees and creators. This brain trust was central to Toy Story and the majority of the success that followed.

Pixar was set up to empower this early group of creators. As the movies got bigger and the teams around them got bigger, Pixar was able to leverage these individuals’ talents to a greater and greater extent.

The magic of information technology is that it allows increased productivity out of one individual. Pixar got leverage by using a huge workforce of animators and computers to multiply the creativity of the brain trust. Media brands today can use tools like GenerativeAI to get significantly more leverage out of incredible individuals. My colleague Dan will have an essay coming out tomorrow with more of our research on this area and how we use AI tools internally to accomplish this ourselves.

The internet allows for infinite free distribution and information technology; AI now allows for leveraged taste.

This isn’t a call for the creator economy to make some grand resurgence. It is an argument that we will see media companies become a lot bigger with far less staffing requirements. I see a path over the next three years where I can publish a deeply researched, 2000 word essay, every single day. Every could simultaneously increase its quality while keeping costs flat. Leveraged individuals would not fix the distribution or monetization issues I discussed above, but for those brands that are able to achieve a critical mass of followers, they will have even higher output and gross margins.

The new media playbook looks something like this:

- Use AI/leveraged Individuals to drive down costs

- Achieve sufficient scale or high-value audience density to lightly monetize with ads

- Attach higher-value SKUs and subscriptions to true believers

For creators, this is the best possible world. If you have a creative gift and you can build a brand, it is a cheat code to earning millions over the course of a career. And you can do it without industry gatekeepers taking it from you. However, the majority of the industry is not even close to being prepared for what is to come. Every aspect of a media company’s P&L, from ad revenue growth to content creation costs, needs to be rethought. We are in for a period of reshuffling, and the collapse of Vice is just the start.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.08.31_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

I'd say media is by FAR the worst industry to be a mid-level or even mid-senior level player in--just permanent Stockholm Syndrome. But if you can somehow hit professional lotto and make it to the top, whether as a Ben Thomposon style who bags millions to think out loud, or as like an old guard cable exec, it's the best industry to be in. One of the most powerful businessman in the world can literally spend his day building rockets yet his heart and head are still more drawn to his fucked up little media toy :)