Welcome to the 408 new readers who joined Napkin Math since last week! Our Napkin Math team now sits at a resolute 16,289. Glad you are here! If you got forwarded this email you can join us below.

When I announced that I had joined Every, a so-called “writer collective,” there was a flood of messages from readers. My mom was kind, “Congratulations, you are my favorite son!” (I’m an only child). My friends were incredulous, “Why did they pick you?” (thanks guys). But the response I got from most internet/media people was “Why are you doing this and what are they paying you?” (a little intrusive).

In response to this, I would like to do something a little...radical. In today’s newsletter, I’ll be sharing screenshots of my contract with Every and the financial model I built to see if I was getting ripped off or not. Yes, this is real.

I’ll talk about how Every’s deal terms work: how much I’m currently being paid, what creative rights I gave up, and why my Napkin Math™ (sorry) said this was the right call. I’ll also share a model you can use so you can do the math to figure out the best online writing option for you. Following that, I’ll also bring in fellow bundle writer Fadeke to discuss why she decided to sign up. Her reasons are very different from mine and equally compelling. You’ll want to make it to the end!

So let’s do a little bit of building in public and dive in.

Content creation is not for the short term

When I first got started in the writing world, the most shocking thing to me was how underpaid writers are. I assumed that a top New York Times reporter would be making equal to that of a top Google Engineer. Both of these high-quality professionals spend their days typing into text editors, are important to society’s function, and are just hard to find. They possess uncommon skills! Arguably, unlike Google engineers, Times writers are less commodified because they have a greater degree of specialization and a brand with audience members. Instead, if you are a normal, non-superstar journalist of 20 years you may hit ~$150k salary. And at the bottom end of the spectrum, the starting salary for many writers in the U.S. is in the $30k range. As a comparison, I have friends who are earning more than that whose job is to pick the color of buttons on apps (they are also less than 3 years out of college). Now you may or may not feel that it is right. But we can universally agree that relative to their amount of private and public influence, writers tend to make very little.

Platforms like Substack and Ghost are succeeding because they let writers go directly to their fans and own their own distribution and payment channels. Thus, writers capture the means of creation and also more of the profit they generate. There are now dozens and dozens of prominently independent writers who are making far north of $500k! (More power to them and may God bless me with similar levels of bread).

But of course, there are a lot of challenges with going the independent route. It is not for the faint of heart:

First, the chicken and egg of audience development. If you are popular for something that transfers well to the written word you can probably port that audience into a newsletter. Everyone from MegaChurch Pastor Jimmy Evans to Nightly Newscaster Dan Rather were able to successfully transfer their fame towards lots of subscriptions. But what if you don’t quite have the fire and brimstone style of speaking that fills stadiums? Or don’t have the authoritative, silky, sexy voice that Dan has? Well you are kinda in trouble. There just isn’t a really great way to have an instant fanbase in the competitive world of newsletters. Yes, there are the occasional previously unknown people that break out, like the wonderful economics writer Nathan Tankus, but the reason we are familiar with these stories is because they are rare! Typically, it is an effort of many months and years to build a profitable media business. Most people can’t invest that amount of time into something as uncertain as writing online. Substack has pursued a strategy of going after whale writers because there is a direct marketing funnel from their popularity. Demand gen is simply difficult when monetization is far away and uncertain. Disclosure, I worked at Substack for a few months last year, before they got as popular as they are and before they started the Pro Program in earnest.

Second, this stuff is hard. Like really, really hard. Producing quality work, week after week, is exhausting. When you start a newsletter you think you are becoming a writer - wrong! Wrong wrong wrong! You are actually becoming a one person media company and are thus responsible for marketing, finance, all operations, and oh yea, writing something worth clicking on a couple of times a week. Keeping that pace up without any external support is taxing. Especially if you are trying to work full-time, it means working every weekend and most nights (trust me on this one). Since so much of this business is momentum, if you take a week off you can watch your growth stall. Yes, you can automate things and yes once you reach a certain level you can coast somewhat—but it is hard to get there.

Third, the business side is complicated. Knowing which tools to select (Substack or Ghost or Mailchimp or ConvertKit or or or) is only half the battle. Understanding your audience, developing a sustainable growth engine, each of these things could easily be a full time job but instead all those jobs are yours. Many top writers end up hiring and managing a small team to enable them to run the business, but that’s only possible once they’re swimming in cash. When they were just getting started and most desperately needed the help, they couldn’t afford it. And like, this isn’t why most writers started this to begin with. They just wanted to write!

So into this competitive world of tools for writers and writers who can be tools, you must birth your fledging publication. So what do you do if you are not well-known, don’t have any influential friends, and are terrible at Twitter? Note: I am describing myself.

Enter Every and their contract

This was the circumstance I found myself in. I had been writing my own newsletter on Substack for about 6 months and was looking to take the next step. My list was growing quickly and I felt like I had product-market fit. Despite not having payment options available, readers tracked down my Venmo account and paid me anyway. I was onto something! But all the problems that I described above were hitting me—I was burnt out. As an intellectual break, I did a freelance piece for Napkin Math about revenue that went well. Because the previous writer Adam was moving on, Every needed someone to take it over. They asked me to hop on a call and Dan opened it with a question,

“Evan, what do we need to do to make your writing dreams come true?”

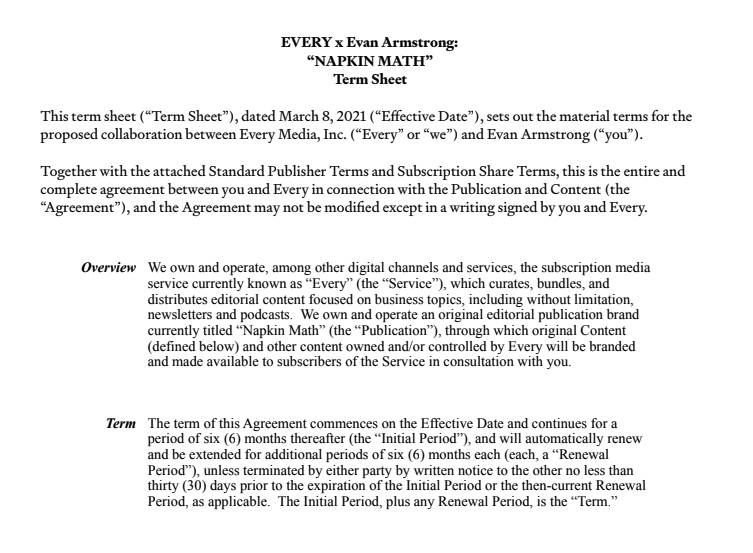

It was a pretty good first line. Frankly, they mostly got me with just that. Writing is so hard and competitive that finding people who treat you with respect is a little stunning. But I am still a rational analyst! They made me the offer and sent over the contract. I’m not going to include all the pages (I swear that lawyers are paid more for overly long, obtuse language) but some of it is below. Note: Feel free to not read the screenshots, it is there if you are interested, but I’ll summarize.

This is super simple! Every and I were entering into an initial 6 month agreement. They would own the Napkin Math brand but I would be writing under it for the next little bit.

Straightforward. But here’s the juicy stuff.

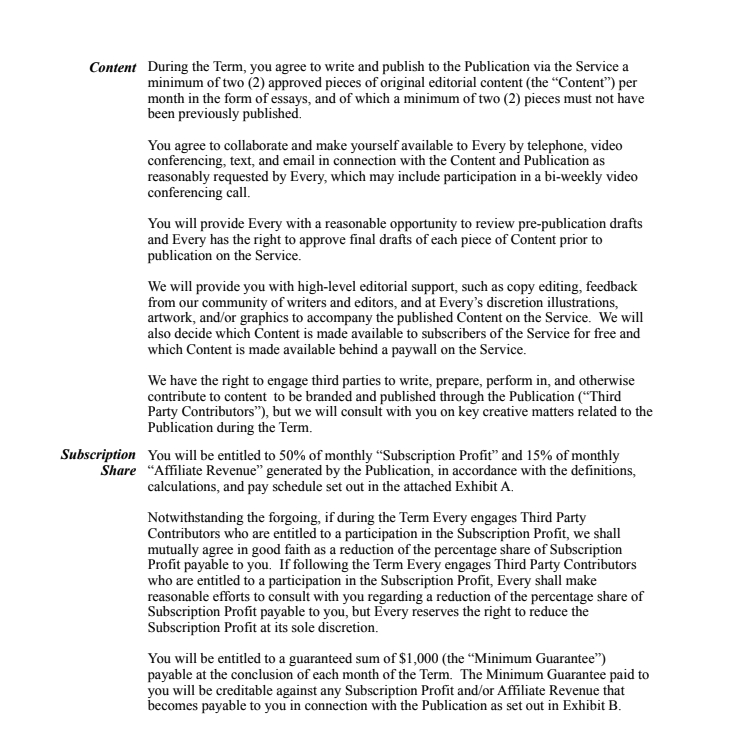

Every asked me to write two articles a month (the financial explainers series you saw start last week) for which they would ensure I get at least $500 per post. Each of these take me ~15 hours. So I am making $33 dollars an hour. This felt fairly reasonable to me! This is my first professional writing gig and looking at it as an entry level job this rate wasn’t terrible. However, the opportunity cost is fairly tough for me to swallow. My freelance time used to be devoted to consulting startups on their Go-To-Market. For that my hourly rate was close to 10x what I’m making as a writer (ouch). So am I being ripped off? (spoiler alert, no).

Show me the money!

The important thing isn’t the minimum rate. What matters is the uncapped upside. The deal is structured such that I receive 50% of all revenue that I generate. This is highly unusual for a media publication. Usually the negotiations go along the line, “You have two choices, my way or my way.” Because writers are so historically dependent upon publishers, they have reduced negotiating power and typically just receive a salaried wage. The beauty of the power dynamics of the internet (and the ethics of Every team) is that they allow writers to capture more of their upside.

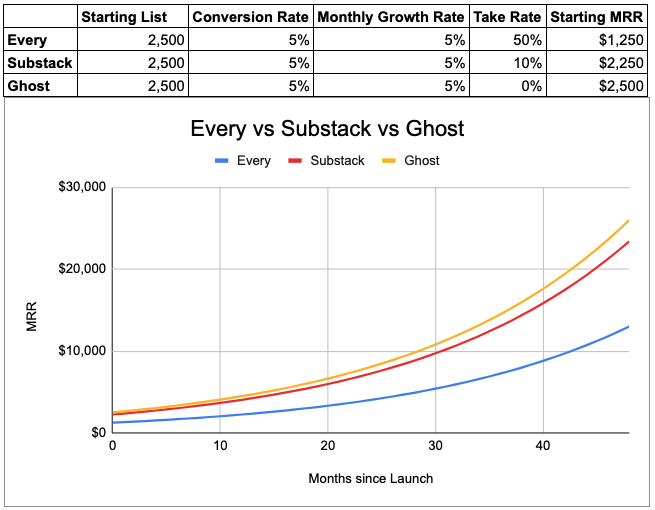

But of course, there is a downside. Instead of 50% on Every, I could be getting 90% on Substack, or even 100% on Ghost. Of course, Every does stuff for me that those platforms don’t (marketing, customer support, esoteric analytics that satisfies my quant itch). The question is how much extra growth I’d need to get from Every’s services in order to justify their bigger take rate.

So I did the Napkin Math™ (sorry again) and realized I only needed 2% more growth from Every to justify their 50% cut versus other options with smaller take rates.

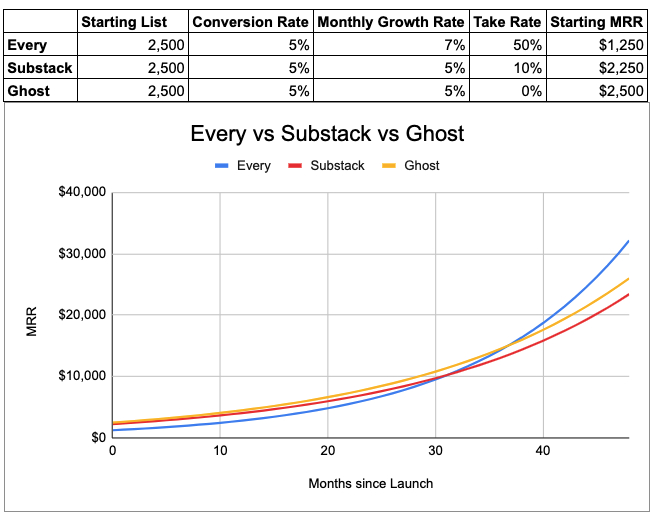

Let’s start with a generic newsletter. 2,500 people on the list and growing 5% a month regardless of platform.

Well...this isn’t great. But wait, Every offers more than a distribution tool! It means I get marketers, podcasts to appear on, and other growth tools included in my 50% take rate. Let’s assume they are bad at their job (they are not) and can only add an extra 2% growth to my 5% existing growth.

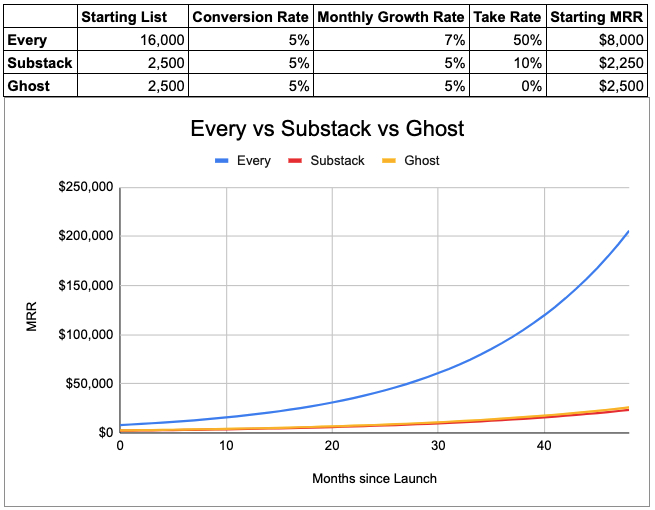

So better, but still not great. But wait yet again! I don’t just get a distribution tool and growth help. I also get exposure to their 30k+ free list (and a little unusually because I’m taking over a preexisting list) a base of subscribers to start off with.

Suddenly, the whole independent thing isn’t looking quite as compelling as it used to. The size of the overall pie turns out to matter a lot more than what percent of it is my slice. Don’t believe me? Let’s quote Substack CEO Chris Best from a recent interview when he was comparing Substack’s higher take rate to Ghost,

“When you get into the economics of these [newsletter] businesses...the thing that you quickly realize is that the thing that determines how much a writer is going to make, how successful they are going to be, is not the fees they are going to pay, it is the growth rate.”

Perhaps even more impressively, this is all with me working ~60 hours monthly. That’s one article a week! If I were on my own there’d be much more pressure to publish more frequently, but in a bundle context I’m happy to write fewer pieces and make them that much better, and lean on my colleagues to help fill out the rest of the publishing schedule. Plus, if I were to choose the Ghost or Substack option, I would be responsible for all the boring stuff (e.g. anything but being a writer). I’ll happily have Every take care of my customer support and marketing. That stuff is important but I would rather spend my time doing literally anything else. It also allows me to keep my day job for as long as I choose (if my manager is reading this I am not quitting anytime soon please don’t fire me).

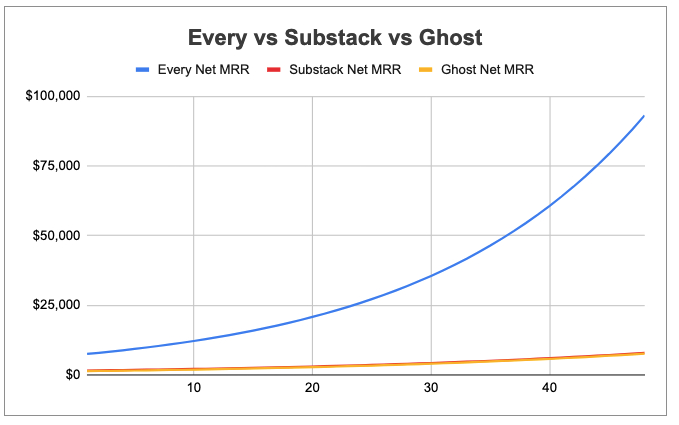

I can feel the shouts emanating from Twitter, “But Evan what about Churn! Pricing arbitrage! Ghost hosting fees! Stripe processing fees!” In response, I created a model that accounts for all of that. This is the one where in 12 months, I’ll be disappointed if I’m not close to this forecast. Note: This model is fairly complex so before you critique this as unreasonable, please play around with it yourself!

On subscription revenue alone, I should personally be making $13,562 a month next April. In 2 years, ~$26k a month. Call me crazy, but I actually think this model undersells it. This doesn’t include ad sales, consulting gigs, or other revenue-generating opportunities the newsletter provides.

Did I mention that they also give me a copy of my email list (both the free and paid subscribers emails) if I choose to leave? This deal really is great for me. It is a testament to aligned incentives—the more I grow, the more they do. They want to encourage me to sign and to encourage me to stay.

Of course, there are some things I’ve given up to get access to this deal. I don’t have complete creative control like I used to. I can no longer take a week off to watch college football. The Napkin Math brand isn’t mine and if I choose to leave Every the brand will stay here. For my finance nerds out there, I’m not capturing the goodwill value associated with the brand. I am still a contractor and if Nathan and Dan don’t like me for whatever reason they can legally fire me without cause. (I would also appreciate it if they didn’t fire me either. You know what, please nobody fire me ever).

In this humble analyst’s opinion, this is the best possible deal available for any skilled operator who simultaneously desires to write. The incentives are well crafted, the money (potentially) life-changing, and most of all, it is fun! I really like writing with the team at Every.

This was the math I ran when I was thinking about joining. But there is a more important aspect of it - the human element. To that end, I asked Fadeke, who launched Cybernaut this week, about her reasons for joining:

Fadeke Adegbuyi: I did a calculation or two, but certainly didn't open up a spreadsheet to create a money model––that's probably why you're writing a tactical newsletter on finance and I'm writing a whimsical one on the internet!

Really, my considerations were much simpler:

- I'm an Every fan. I've followed and read Divinations, Superorganizers, and Means of Creation long before I joined and when it was the Everything Bundle. Having my own publication alongside others in the bundle was a genuinely exciting prospect.

- I get to work with an excellent editor. Each publication at Every gets an assigned editor. I'm privileged to work with Rachel Jepsen, whom I've worked with before and respect a lot. I think a lot of people who have never worked with an editor think it's crossing t's and dotting i's. That’s not the case. Working with an excellent editor can transform your work and make you a better writer. I'm essentially getting paid to do an MFA.

- I get built-in distribution. While I don't think we've reached peak content, it's increasingly harder to have your work noticed in a sea of newsletters and podcasts. Unfortunately, it's not always the best writing that wins, it's the writing with the most reach. Working with Every allows for both––the space and the resources to create high quality work and the distribution channels to ensure it gets seen.

- I drank the writer's collective kool-aid. I've wanted to write about internet culture for an embarrassingly long time. Joining the bundle was a forcing function that finally pushed me to do it. There's a level of accountability and community that comes with being in a collective that's hard to replicate independently.

Evan Armstrong: Isn’t she awesome? Fadeke is such an elegant writer and thinker, I love her perspective on this.

In sum, I think the value of joining a writer’s collective is incredibly compelling. The strong alignment of shared incentives, both financial and personal, means each of us wants the other to succeed. When one of us wins, we all do.

I do want to be honest. Even hypothesizing about this amount of success frightens me a little. Growing up in rural Minnesota, I didn’t know people made this sort of money. That I have the slightest chance to even get close to what my forecast predicts is nausea-inducing. Know that I treasure every dollar and minute you trust me with. I track all of it and recognize what it means. Thank you for being a subscriber and please respond to this email or DM me on Twitter if you have any questions.

Till next week,

-e

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!