Sponsored By: Ana

This essay is brought to you by Ana, your personal news AI assistant. Ana reimagines how you interact with the news—simplifying stories, cutting out the endless scroll, and answering your questions. Ready for a refreshing news experience? Get involved today and download Ana through TestFlight.

Can a single person use AI to build a billion-dollar company? That’s the question Evan Armstrong posed in February, responding to a prognostication by OpenAI’s Sam Altman. With OpenAI’s DevDay set for October 1 and Every taking a quarterly Think Week to step back and evaluate the tech landscape, we felt it was a perfect time to republish Evan’s look-ahead from earlier this year.—Kate Lee

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

In a February interview, OpenAI cofounder Sam Altman said:

“We’re going to see 10-person companies with billion-dollar valuations pretty soon… in my little group chat with my tech CEO friends there’s this betting pool for the first year there is a one-person billion-dollar company, which would’ve been unimaginable without AI. And now [it] will happen.”

Altman’s idea is that AI tools will soon reach the point where they can replicate the entire output of human employees. Instead of needing to hire a designer, you can use, say, GPT-6 to design something entirely for you. There will be far less need for software engineers (meh), sales staff (no one will miss them), and newsletter writers (a tragedy of Greek proportions, leaving our society barren and empty).

An ambitious founder could outsource the work of employees to an army of artificial intelligence agents. Theoretically, this would allow entrepreneurs to focus on only tackling their most important competitive advantages.

This is a claim worth examining, not just because I would like to be the first person to build that billion-dollar company. The one-person billion-dollar company matters because it is a handy way to understand how AI will disrupt knowledge work. In a good world, Altman’s prediction would come true because AI would allow people to build whatever they can dream up. In a bad world, it would become true because AI will make most people’s jobs irrelevant, concentrating power in the hands of the elites.

Writing is perhaps the most obvious use case of AI. All of these AI companies have my life’s work squarely in their crosshairs. It makes me wonder if the consumers of the future will even want writers in their life. This is a deeply important question for me personally, because, you know, student loans. Is there a way I can use these same tools to build a billion-dollar company of my own? Can I use the instrument of my career’s destruction as my financial savior?

But let’s start with a more basic question: Is anybody close to achieving this today?

Imagine a news experience where you're in control—where you're not overwhelmed by headlines and can easily digest the news. That’s Ana. With fewer stories, FAQs on each piece, and the ability to ask questions, Ana offers a more interactive, insightful way to stay informed. Say goodbye to endless scrolling and get straight to the point with Ana. Try it for a week through TestFlight and see the difference.

What are the closest proxies?

First off, we need to lay some ground rules. Altman is talking about a billion-dollar valuation for a company—which is not a rigorous metric. As I wrote in January, valuations for startups are made up anyway. I’m pretty sure that if Sam Altman tweeted, “I have an idea for an AI company,” he could raise a round that valued his company at $1 billion. (This is essentially what happened with OpenAI cofounder Ilya Sutskever’s new company, which is currently valued at $5 billion.)

What I want is a real business, one that has healthy profit margins and judicious revenue growth. To keep things simple, let’s say that our one-person billion-dollar company has to have at least $100 million in annual recurring revenue (ARR). Then, if the company is hot enough to attract investment, it could probably get a 10x revenue multiple, valuing it at $1 billion.

There is no company that even comes close to qualifying.

In the technology sector, the most recent example is Midjourney, a generative AI imaging startup. It’s never raised outside capital, it has fewer than 100 employees, and it reportedly has more than $200 million in annual revenue. Not bad! But it is still disqualified on an employee volume basis. In 2012 there was Instagram, which Facebook acquired for $1 billion, but it had 13 employees and no revenue, so that’s out. Alternatively, I have a few friends who run $1–10 million ARR SaaS companies with no full-time employees—but that’s because they contract with part-time, low-cost developers, which feels like it violates the spirit of the exercise. Plus, those companies are a tenth of the size we need to get to the billion-dollar mark. So no dice in the private tech sector.

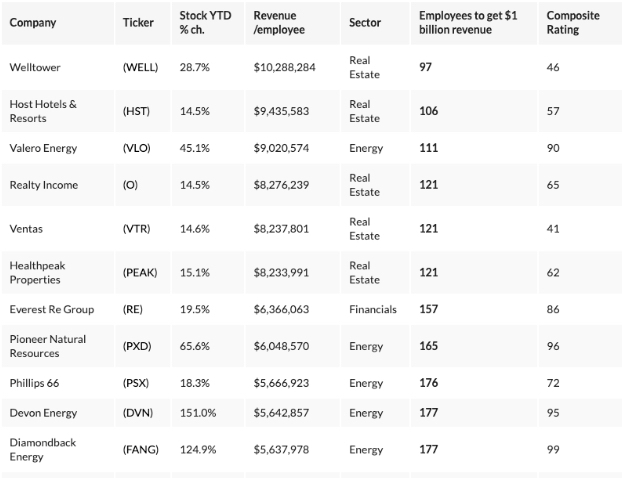

In the public markets, investment and energy firms come closest to meeting the bar. This data set from 2020 provides a sense of what they look like.

Source: Investors.com.These firms don’t pass muster because they are a tenth of the size needed on a revenue-per-employee-basis, have too many employees, and are more like Russian nesting dolls than real, meaty businesses. Subcontractors outside of the publicly listed corporations are doing a large chunk of the labor, again violating the spirit of the rule. Plus, I’m skeptical that ChatGPT will be able to work on an oil rig.

So, fortunately or unfortunately, Altman’s prediction isn’t close to coming true (yet).

Creation goes to zero

The reason why is fairly obvious: The AI technology isn’t good enough. Autonomous AI agents are far from being sufficiently powerful to fully replace employees. Altman’s CEO betting pool isn’t a bet on the rugged individualism of entrepreneurship—it's a bet on technology improvement curves.

But let’s wave a magic wand and say that, starting right now, AI is good enough to swap with humans. What happens?

Assuming that everyone has equal access to the technology, you get what I call Syndrome Syndrome. Syndrome was the villain in Pixar’s 2004 movie The Incredibles whose signature line was: “If everyone’s super, nobody is.” Syndrome Syndrome is what happens when everyone has access to the same technology at the same time. If everyone has an AI agent, nobody has an AI competitive advantage.

However, Syndrome Syndrome does not mean that everyone will be equally skilled in using these agents. As Dan argued,

“But what happens when that very skill—knowing and utilizing the right knowledge at the right time—becomes something that computers can do faster and sometimes just as well as we can? We’ll go from makers to managers, from doing the work to learning how to allocate resources—choosing which work to be done, deciding whether work is good enough, and editing it when it’s not. It means a transition from a knowledge economy to an allocation economy. You won’t be judged on how much you know, but instead on how well you can allocate and manage the resources to get work done.”

He’s right. And as anyone who has had a boss will tell you, there is, to put it politely, a variable distribution of ability on managing employees. The same distribution will be present with AI agents. Some folks will be better at it. However, any market in which companies can earn $100 million in ARR will attract many competent people. Big opportunity brings big competition.

Let’s say that OpenAI gives everyone access to powerful AI agents. Now you can outsource anything that a remote employee could do for you. You can build an app in an hour or make a video game in the space of a Zoom call. This is amazing! But that also dramatically increases the total supply of digital goods.

As I’ve been arguing since September 2022, AI sending creation costs to zero will only make generating demand more expensive. There is a limit to the number of digital goods the world needs. If AI makes it essentially free to build anything involving a computer, these goods will grow more specialized and more competitive, thus shrinking margins. Any use case that is a broad, horizontal need—like spreadsheet software—will have incumbent software companies eager to protect their business. Microsoft is still going to crush you.

I will front-run my critics—these assumptions are crude. The nuance of building, of making sure that your company fits the culture of your market, goes far beyond “have good idea and sell real fast.” The heavy-handed limits of my argument are the point. By pushing our assumptions to their breaking point, we can find a more reasonable path.

To reach $100 million in ARR, founders will need to have an advantage in both taste and distribution. Taste will enable founders to have a unique insight into their customers’ problems to solve, while distribution will allow them to rapidly market their solutions. Remember, if AI agents are as powerful as Altman is predicting, someone can build an idea the instant they have it. So the only edge comes from having the quality of taste to generate the idea first and better, or in distributing it faster and more cheaply.

What companies can be built?

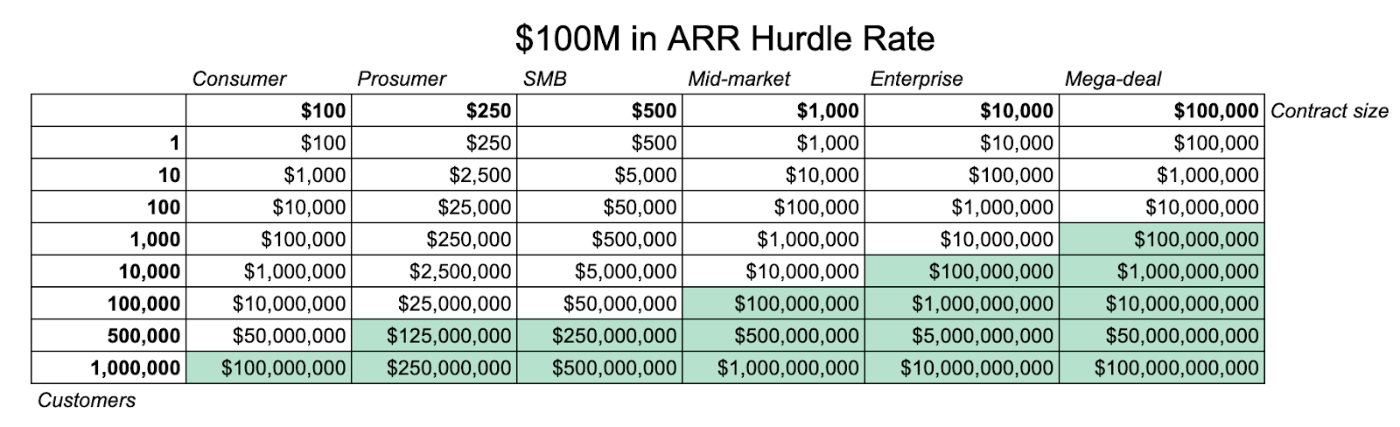

Even if you have exquisite taste and great distribution, building a $100 million ARR business is just so damn hard. Here is what would be needed on the basis of customer volumes and ARR amounts:

Every illustration.On the left side are consumer products, like a media subscription, charging a total of $100 in ARR per customer per year, which would require 1 million paying customers. By comparison, the New York Times has roughly 10 million subscribers while employing 5,800 people. The solo founder has to sell 10 percent as many subscriptions as the Times with .017 percent of its staffing. On the right size is big, meaty enterprise software contracts, which have their own unique challenges. A grand total of zero of these green boxes are easy to pull off.

Solo founders are limited to organically selling off of someone else’s distribution rails. Essentially, you have to Xeet (is that what we call a tweet now?), email, Facebook-post, or YouTube-announce that you’ve built something. From there, the product hopefully has built-in organic growth loops that allow it to spread over time.

In the short term, success becomes a simple equation of audience size * product efficacy. The bigger and more valuable the audience, the better. The more urgent and expensive a problem the product solves a need for them, the better. On the left side of the table, a consumer business would need a massive audience to pull off the $100 million hurdle rate. Unless you happen to be The Rock or Oprah, I wouldn’t worry about this one too much. But if those individuals read this article, here’s a tip: You can build a media product and sell it (think: “The Rock’s Workout Plan”).

The difficulties abound on the right-hand side of the chart as well. Enterprise- or mega-deal- size contracts will almost certainly require some degree of hand-holding. A customer will expect to be able to talk to a human being if they are forking over $10,000, but it would be impossible for a solo founder to take 10,000 calls a year. And a product that services customers who are able to pay that price is likely highly technical and unlikely to be a one-and-done transaction. Maybe AI agents can do migration and nuanced customer support? Who knows.

This raises another point: The closer your product is to being able to solve a distinct problem for a customer, the easier it is for a customer to build it themselves. Syndrome Syndrome endows everyone with the same technical tools. Instead, the prospective solo founder needs to solve a problem that customers don’t even know they have until you offer them the solution.

Am I going to make it?

Frankly, I remain unconvinced if what Altman has outlined is possible. The size of distribution required, coupled with the ability of anyone to make anything, makes it incredibly challenging, if not impossible.

That being said, I am convinced that in a world with AI agents, there is a significant opportunity for ambitious people to build businesses in the $1–10 million ARR range. Anyone who has suffered through the trench warfare that is building a company from scratch knows this truth: A company is built on details, not frameworks. It is all the little things, the small touches of craft and culture, that determines that long-term success of an organization. A solo founder will be able to build a small product that is a manifestation of their taste. And, if it turns out that the opportunity is huge, they should probably hire people to help grow anyway.

You have to start somewhere you know and see where it will take you. In February, Jason Fried, the co-founder of the company 37signals, tweeted about the goal when he started selling its first piece of software:

“It was a project management tool that we made for ourselves… We figured if we needed it, plenty of others probably did too… You never know what's going to happen until after it happens. And happen it did. We had this idea that, I don't know, if we could maybe make $5,000 a month after the first year, we'd be on to something… Turns out that we hit that $5000/month mark in a few weeks.”

Just build the biggest audience possible, solve problems for them that no one else can, and the rest will take care of itself.

So to return to my initial question: Am I in trouble? After doing all the math, I feel confident. My newsletter’s product is not words—it is trust. The outcome from me publishing rigorous, accurate analysis for years now is that (hopefully) I’ve earned a level of good will from all of you. If or when AI makes it such that words are no longer hard to make, then trust will translate into whatever medium comes next. In a future where AI makes products cheap, investing in distribution will be the wisest bet.

Evan Armstrong is the lead writer for Every, where he writes the Napkin Math column. You can follow him on X at @itsurboyevan and on LinkedIn, and Every on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

If you believe you can't, you won't. In 2018, there were 41,666 Million Dollar businesses with only 1 person and that was without AI. I'm taking up Sam Altman's challenge, because anything is possible if we but believe and take massive action.

Melvin H Waller