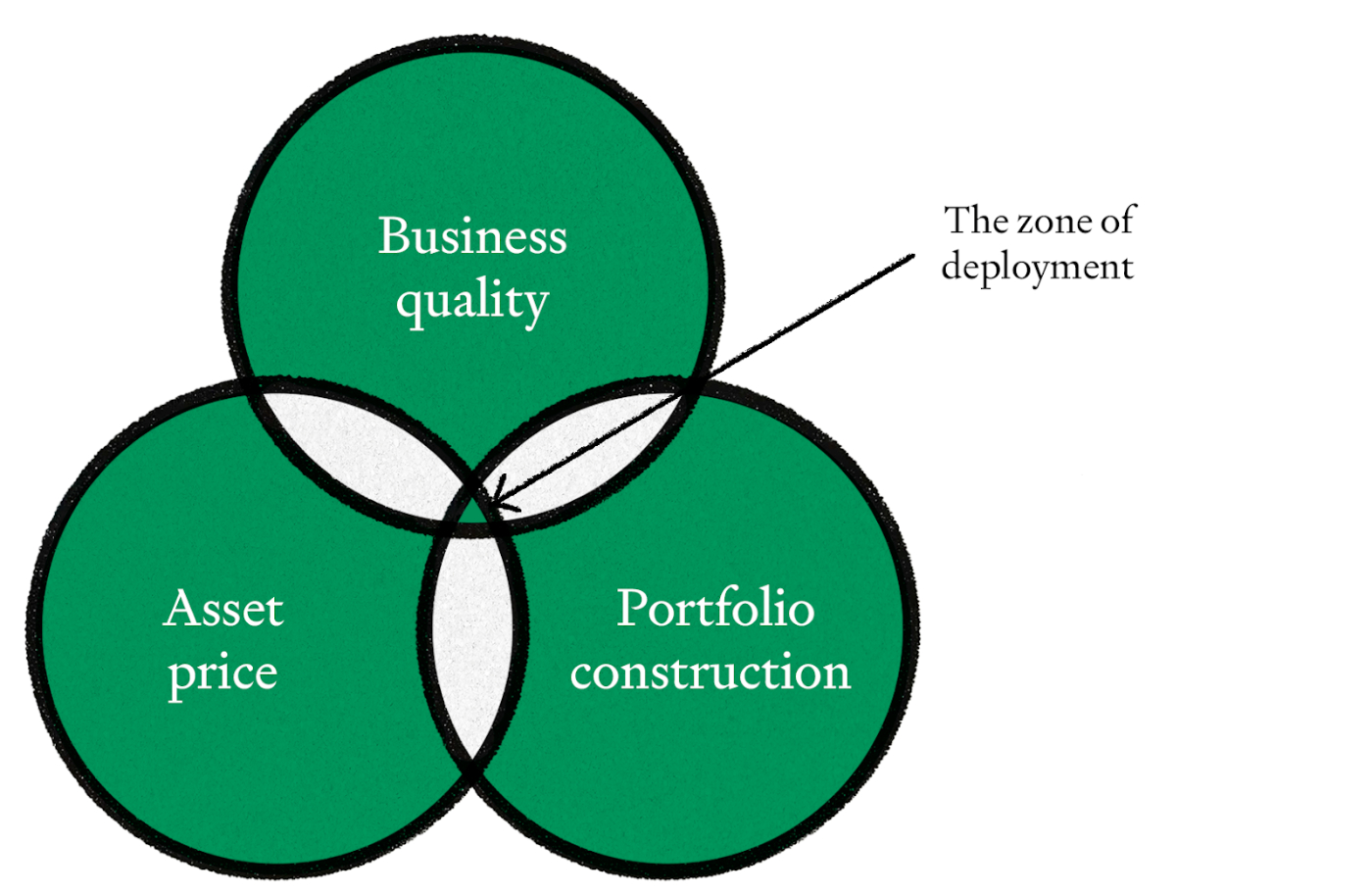

When you are looking to deploy capital, you have to keep three things in mind:

- Business quality: Is this a fundamentally strong business?

- Asset price: Does this price make sense?

- Portfolio construction: Does the opportunity cost outweigh the return?

It is only if all three of these things are fully understood that you can enter what I call the zone of deployment—the space where you should be willing to invest.

Every illustration

I don’t know if it is because David Fincher made such a banger with The Social Network or the VC content marketing machine is so relentless, but we’ve mostly focused on business quality over the last 10 years to the exclusion of the two other criteria. The stars of Facebook, Google, and Airbnb loomed so bright in our eyes that we began to believe that the only way to measure business quality was by a company’s ability to quickly scale to an enormous size. And we mostly funded startups we believed could achieve that.

The problem? Businesses that can “grow so fast nothing else matters” are more rare than you think.

Only 1 percent of startups return 10 times the invested capital. In public stocks, only 2 percent of public companies are responsible for 90 percent of the wealth creation in U.S. stock markets.

This means that if you want to get stupid rich via a venture-backed startup, you will need to select the 1 percent of the startups that raise seed capital every year—so one of the 80 of the 7,964 startups funded in 2023—and hold onto that equity for about 10 years. Then, even if you are lucky enough to have said company go public, you have to hope it becomes one of the roughly 10 companies that drive the majority of public stock returns. This math is a bit handwavy, but the Napkin Math™ for you to get wealthy off startups is about 2 percent public of 1 percent startup, for odds of .02 percent. Eek.

When I ran this math past my VC friends, they all said some variation of, “Those odds feel a little high.” Eek times two.

Of course, this math doesn’t apply to every tech company. There are lots of ways to get rich in our business, but the method can’t simply be to “pick quality businesses.” Investors and founders have said that they care about price or portfolio for years when instead, they loosened their definitions—they all believed that they were picking and running unicorns. When coupled with excess cash from low interest rates, there was an artificial inflation of both the value and volume of startups.

In 2013, when the term unicorn was coined, the initial cohort included 39 companies, with 62 percent either going public or being acquired. Today, an analysis by Cowboy Ventures clocks 532 unicorns with 93 percent of them not having an exit. CB Insights pegs the total number of unicorns at over 1,200. (Most of the difference comes from definition and geography.) I would estimate that over 50 percent of these businesses will fail to have a positive outcome for employees and investors, and most of the failure will happen by the end of 2025.

It’ll be a bloodbath.

We're in a realignment phase. This column has been warning for over a year that tech’s operating paradigm is changing. Venture capital funds have to evolve beyond simply stuffing 10 companies full of cash. Their zone of deployment needs to become more expansive. On the other side of the coin, founders will be able to reimagine what kind of companies they can build and be proud of.

If you are a cynical asshole (like me), you’ll note that the zone of deployment is not perfect, and each criterion can be picked apart. In my mind, quality is a complex matrix of factors: long-term defensibility, platform risk, profitability, cost structure, and more. But for other, more meme-driven investors, business quality is determined solely by the volume of rich morons willing to buy their position. Asset prices exist as a direct effect of the quality of the business. And portfolio construction? Well, actually, that phrase is clear, but it sounds boring, so we’re gonna ding it for that.

That these categories are fuzzy is both the problem and the point. Because each term is a matter of personal, socially constructed preference, people can easily justify any investment decision to themselves if they don’t have guardrails in place.

This investing dynamic especially matters in tech because I think we’ve gotten business quality so wrong over the last 10 years.

You can interpret a shift towards the zone of deployment with fear—after all, this change will remake the industry. Instead, what I advise my founder friends is that this is a good thing. A higher focus on quality, price, and portfolio construction means that a founder should feel empowered to go their own way. They can absolutely swing for the fences and raise lots of VC dollars. Or they can step back and do something weird, independent, and different.

Nearly all of our advice and behaviors were built in the 2010s, an operating era defined by going big or going home. Now, it is time for something more expansive.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

I got to the end of this article and I felt like it ended halfway through. I'd love to see more on the types of companies and the new paradigm for founders in the next five years, which is a combination, as you say, doing something weird and wonderful or sucking up VC dollars.

@hollywoodsign thanks for the feedback! I always worry that my usual length is too much, so was trying for shorter and punchier, sorry it didn't land for ya.

I'm tracking with the gist of this and appreciate the piece, but the suggested math is solving for "getting wealthy" which means we're handwavy (a fantastic term, btw) on both sides of the equation.