Popular convention is that startups are high risk, high reward, while public companies are safe but less likely to make you rich.

This is only sort of true. Startups follow a power law—only 1% return 10x the invested capital.

The dirty secret is that public stocks operate similarly. Only 2% of public companies are responsible for 90% of the aggregate wealth creation in U.S. stock markets.

A more use-one-finger-to-push-your-glasses-up-your-nose sort of way to restate this: wealth creation is almost wholly concentrated in a minuscule percentage of companies, regardless of whether the underlying security is publicly tradable. So the advice I was given when I started my career—work at a startup to get rich instead of working at a corporation—is false.

A career is essentially a trade where you pour your single most highly concentrated asset (your life) into the most highly diversified asset of all time (a 401K retirement fund) until one day you die. Perhaps the advice to “work at startups and get rich” is a case of survivorship bias. It seems like the lifeblood-to-Vanguard-trade doesn’t work—instead, it’s a trade of lifeblood for stock options. You either make it rich or you make nothing, as noted by my own startup career, where I have literally never had a 401K program and have yet to have a major exit.

However, this is too simplistic a read on the data. What matters with equity isn’t total wealth creation, it is being able to time the sale of the asset. The midwit take on the power law would be that an investor should hold a stock as long as reasonably possible. If you have some asymmetrical advantage of getting at these 1% of startups that then turn into those 1% of public companies, you should keep that stock for decades at a time. The ideal strategy is to find the next Microsoft and keep that stock for the next 40 years.

But that’s, like, kinda impossible. If it were as simple as “buy at the bottom, sell at the top,” every Adderall-snorting Robinhood user would be drowning in Lamborghinis. Unfortunately, because the future has the pesky attribute of being unknowable, timing the sale at the top is very, very hard. Firms that are currently attempting to invest at the seed stage and hold through a company’s public lifespan, most prominently Sequoia Capital, are essentially betting that they know the companies they are holding better than their founders, who tend to not understand their own company’s potential.

After all, the value of two of the most startlingly successful technology companies, Microsoft and Tesla, have both been underestimated by their founders. Bill Gates owned 49% of Microsoft in 1986 and has reduced his ownership to about 1%. If he had held, he would be worth about $1.22 trillion today. Instead, he has diversified away to about a $112 billion net worth. Elon tweeted in 2020 that “Tesla stock price too high IMO,” causing the price to drop 10%. He has also continued to sell off his shares.

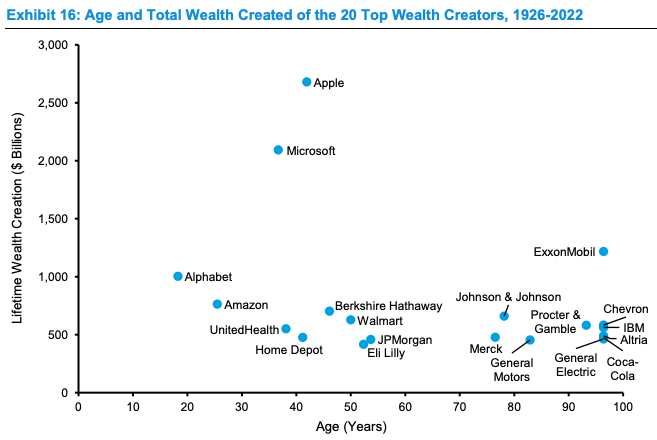

This graph visualizes the top wealth-creating companies since 1926 relative to their age in the markets.

For all of the older companies, their days of ginormous wealth creation are probably behind them. And while you could probably argue that General Motors will make a huge comeback with its leadership in autonomous vehicles, I’m not sure that is right! But still, the argument exists. Which is yet another illustration of how hard this knowing-when-to-sell problem is. At various points in their lives, both Apple and Amazon stock have fallen over 90% (Apple before the Jobs revenge tour era and Amazon after the internet bubble burst). Every company has a lifespan where it peaks in value and slowly decays thereafter. No company goes up forever, so you have to figure out when to sell.

All of this is a very roundabout way of saying that the public versus private dichotomy of investing is nonsensical. Since both markets are subject to equal levels of power law, the wealth creation potential is equal in a hand-wavy way.

Instead, forced constraints are what matter. Allegedly, in 2014 Fidelity did a study of its best-performing accounts. The ones that had the best returns were those of individuals who forgot that they had accounts with Fidelity and just let the money sit there. (I have been unable to find a link to the original study, but I have heard this often enough that I’m going to accept this financial urban legend as a fact.)

Startups are great for wealth creation, not because the risk/reward ratio makes sense for employees, but because employees are unable to sell. They have no choice but to wait 10 years for a massive liquidity event. In contrast, 99.999% of folks would be unable to handle holding a public stock for that long. The issue for labor is that when a company pays you in a mix of equity and cash, only public company stock can be sold when you want or need to.

Really, labeling a company as public versus private is a definitional bundle around these questions:

Exit liquidity

How often do you sell? Who is buying it and why?

- Private: Once every 10 years or so. Sophisticated investors who think there is lots more upside.

- Public: Every single moment of the day.

Pricing forces

Why do you have access to the deal? How does that affect prices?

- Private: Price is determined by a small set of bidders making the price more likely to be irrational.

- Public: Price is determined by an essentially infinite number of bidders. Sometimes that makes the price more rational, sometimes more subject to manipulation (i.e., Gamestop).

Risk category

Why is someone willing to sell this equity to you? What risk are you taking on by purchasing that equity at this moment?

- Private: Can this company work?

- Public: Can this company scale?

Rather than the false dichotomy of public versus private, each investment you make should be evaluated on these three metrics. Too often people think they are making a bet on the company when instead they are actually betting on the inherent structure of the equity.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.08.31_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Love your work Evan