Sponsored By: Equals

This essay is brought to you by Equals, a next-gen spreadsheet with native data connections, versioning, and collaboration. Spend less time pulling numbers and more time drawing insights.

My great-grandmother’s toilet was a hole in the ground until she was 61 years old. Despite bathrooms being common in America since the 1880s, she was unable to afford indoor plumbing until 1963. Her family lived off the land by hunting, fishing, and farming in the summer and eating canned veggies from their garden in the winter. When I asked my dad about his memories of visiting his grandparents, his most vivid recollection was of “having to bathe in a bucket.” The last time I went to our ancestral home in the hills of rural Virginia, this was no longer the case. Water was abundant, and there was a small grocery store nearby (it had a public bathroom).

It isn’t as if we have solved the problem though. Studies estimate that 500K Americans don’t have access to indoor plumbing. Even in San Francisco, the technology capital of the world, nearly 15K people, mostly low-income renters, don’t have functional toilets. How can this be? We have had the science figured out for hundreds of years, so why can’t we fix this?

The answer to this question usually depends on your political ideology. Some blame the rich tech bros for pushing up the cost of housing. The billionaire set blames the left and their restrictive regulations. The YIMBYs blame the NIMBYs. The city government blames the state budget, which blames federal policy, which blames the UN goals, which blames.... You get the idea. Of course, someone out there has the right answer. However, the myopic discourse that is now the norm for politics-adjacent issues makes the truth nearly impossible to uncover.

Meet Equals — a modern, collaborative spreadsheet with built-in connections to databases, data warehouses, and tools like Stripe and Salesforce. Equals means no more stale analysis. Live data is fed into your spreadsheet without having to copy and paste, download a CSV file, or ask your colleague where those numbers came from.

Equals is a fan favorite among founders, engineers, and product managers alike. Teams auto-update reports and models, develop internal workflows, and enable self-serve access to data with Equals. Most importantly, they save hours every week.

Watching the SVB debacle has similar shades of this argument, partially because people have behaved pretty shitty. But also similar lines of debate have formed around the bank's failure. Some blamed the bank’s leadership team, some the VCs who sparked the run, some the Federal Reserve, some the founders. And again, someone(s) does deserve the blame here! But by the time this is all figured out, we will have already moved on to the next scandal. The best we can probably hope for is some form of token regulation to prevent this level of leverage and customer concentration in midsize banks.

However, in the midst of all-caps tweets and salvos of prose careening back and forth between tech and socialist publications, I’ve seen new startups launch that are attempting to solve the uninsured deposit problem. I’ve seen multiple SaaS startups, themselves worried about funding, improve their product to provide more coverage, cover payrolls with their own balance sheet, and onboard hundreds of new customers. They did not solve the problems of interest rates, but they did all they could for thousands of people, all in the space of 72 hours. Six days later, I watched as we publicly birthed three gods in miniature, with the launch of multiple AI models, including GPT-4. Yesterday afternoon, as I sat and procrastinated writing this essay, I saw a drone delivery system launch that claims to use 34x less carbon than driving a car.

Despite all of this, the SVB discourse dripped with vitriol, targeting not just the culpable VCs but technology startups in general. I’m not going to link to any of the articles/tweets, but if you just search for tech bro or VC on Twitter you’ll easily find the anger I’m referencing.

I understand making fun of VCs—you can and should mock them mercilessly. People making millions are auto-enrolled in the jokes-at-my-own-expense club. But the technology sector and startups have merit and value that I fear is being lost. I get where the anger is coming from. In the past six years, we’ve seen the ways software—accidentally or otherwise—can make more problems than it solves. But there are a few reasons why I continue to believe. It comes down to this:

- A startup is a permissionless way to improve society

- Startups make things cheaper, which is a moral good

Innovation is systematically undervalued at solving these problems, and you should consider it a good addition to more typical solutions. If you wanted to fix SVB, you would need to band together Democrats, Republicans, Libertarians, and SF Socialists into some sort of loose coalition of policy reform. Or, you could just go build a better bank that requires buy-in from only one party: customers. You are selling to willing buyers at the current fair market price and that’s it. That’s what we saw over the weekend with those startups attempting to solve SVB-related woes.

How could you fix the plumbing problems of San Francisco? You could band together the landlords, renters right advocates, city governments, and nonprofits to come up with some sort of policy. Or, you could invent and sell a toilet that is cheap and functions regardless of how well the rest of the plumbing in the house works. You may say, well, that toilet sounds impossible. Yes! That’s the point! Technology is the way that impossible becomes realized. Someone needs to invent it.

Do regulations and community co-ops matter? Of course. They serve a role that is crucial and important and irreplaceable in society. However, only a startup can be created by the furious genius of a lone tinkerer in their garage. In the face of such overwhelming political complexity that feels, frankly, outside of anyone’s control and expertise, a startup where people pay to solve a problem feels delightfully straightforward.

What is so inspiring about technology companies is that they are, by nature, deeply individualistic. They can be started in three months by some spunky 20-year-old with a dream. No permission required. That same 20-year-old might get nowhere with banking and plumbing reform, but they may stumble into a whole new way to take care of business. And to be fair, many of the problems resulting from tech’s dominance can be traced to the individualistic nature of the endeavor. By reporting to no one, these young entrepreneurs may end up causing consequences, like, say, riots in Washington, D.C.

These consequences and rewards are more nuanced than a simple explanation of public action versus private markets. It also comes down to which tech startups get funded and why.

Software’s problems and hardware’s demise

In theory, a technology company applies new science to old problems and then scales solutions to as many people as possible. This sounds great. However, it doesn’t really work like that anymore. When you’re trying to understand the startup industry and its associated problems, you have to grok how the internet simultaneously made and broke us.

In the early days of Silicon Valley, the companies were mostly focused on tech such as transistor chips and microprocessors. Venture capitalists would invest large amounts of up-front cash to systematically de-risk the business and then reap massive rewards on the other side. But the industry rapidly expanded beyond its silicon namesake to other areas of science, like recombinant DNA in 1977 with the launch of Genentech (a startup made possible because one of the co-inventors of the technique left academia).

In the even earlier days of the technology industry, say, with companies like General Electric and the electrification of America, there was no formalized VC model. However, there were groups of truly insane people who took on the risk profile of a VC—they just didn’t specialize in the asset class.

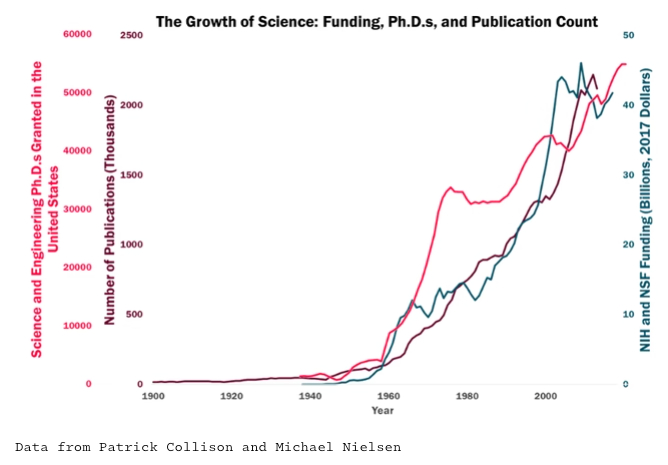

But something weird happened in the ’70s, right as the VC industry really started to kick into high gear. Science began to slow down. But the funding model didn’t: Science funding, publications, and PhDs have boomed since the ’70s.

However, the actual speed of discovery did. Study after study and book after book after book have pointed out that since the 1970s we have seen a dramatic decrease in scientific productivity. We have seen only incremental gains in fields like farming, automobiles, and flight. Revolutions on the scale of electricity or antibiotics are mostly distant memories.

Keep in mind, technology companies are science applied at scale. When science slows down, you should theoretically see an accompanying slowdown in tech startups. But there were two important exceptions in Silicon Valley. The two things driving the industry for the past 30 years were the personal computer and the internet. Personal computers allowed for the automation of knowledge labor while the internet allowed for information services to scale, at zero distribution cost, to the entire human race.

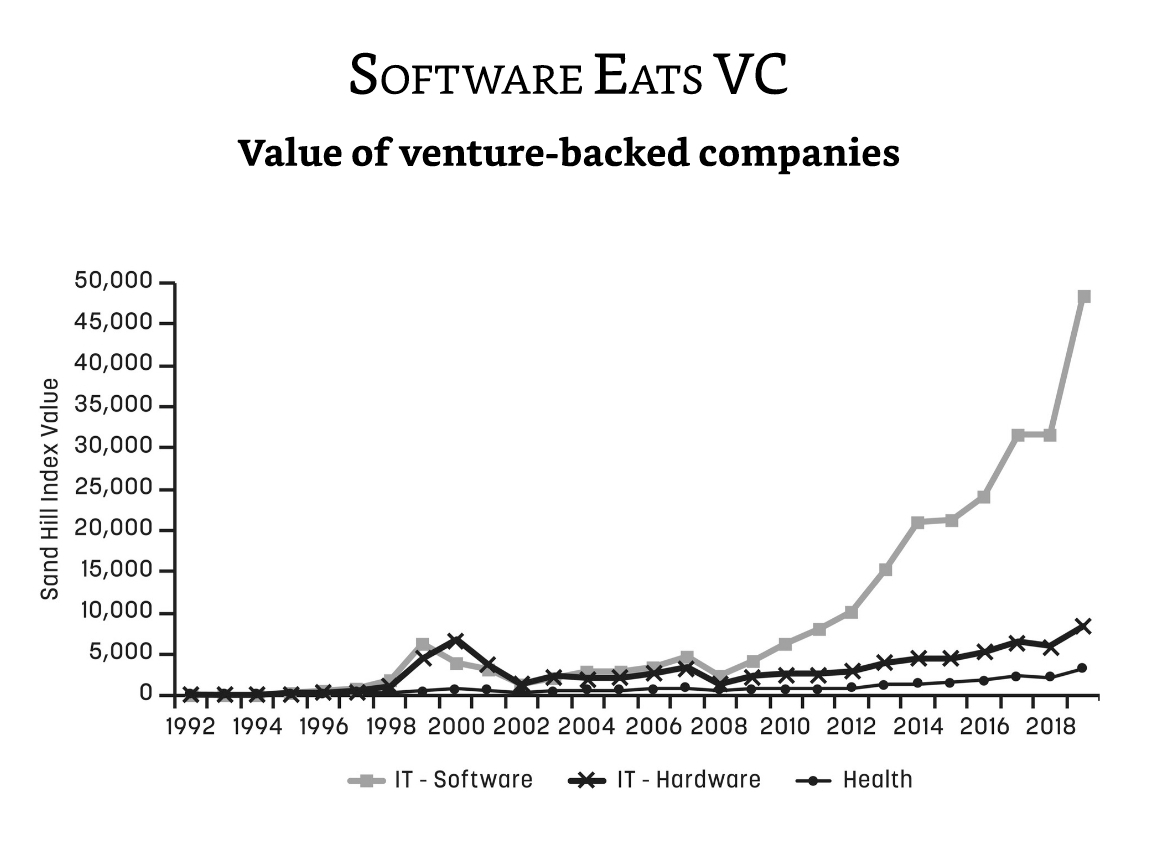

The innovation of the internet in particular was well-suited for the VC model. Software is expensive to build, but, once built, can be sold at zero marginal cost. The resulting financial profile is so compelling, with gross margins averaging around 80% for SaaS companies, that all other areas of technology investment became relegated to the back room. Venture is designed for a company whose profit and loss statement looks like a software company.

Said another way, the science has stayed the same, but the markets got far, far larger. Not only did software scale to the planet, but it was also self-referential. We built software for the software (to help it run better). In some instances, these solutions go three to five layers deep. It’s a money-making ouroboros. These factors combined together resulted in: 1) huge financial returns for top players in the field, and 2) an absolutely predictable rush of capital toward software.

The internet is amazing and software is incredible, but when you’re making information cheaper and easier (versus the physical labor/science improvements of yesteryear), negative and unexpected externalities start popping up.

Take COVID for example. When the pandemic struck, every single convenience we enjoyed was made possible by a venture-backed startup. Zoom to video chat, Instacart and DoorDash to get food, Facebook to connect us with isolated loved ones, Slack and Gmail to continue working (for better or worse)—all from venture-backed companies. Many of these have negative externalities. Zoom overuse crushes the soul, Slack hardwires your brain to fear the sound of a ping, Facebook sort of caused the January 6th riots, DoorDash stole tips from its delivery drivers, who work very hard for little pay. Despite all this, without internet-based VC-backed startups, we would’ve been truly, totally screwed during the pandemic.

But that’s not even the biggest effect that VC/startups had during COVID. The most compelling innovation was the mRNA vaccine pioneered by Moderna, a company that was not only funded by VCs, it was also incubated in-house by them. Its product is a real, physical piece of science that a technology company scaled to the tune of tens of millions of lives saved. However, that was the exception. Most capital goes toward whatever latest software or internet company is flashy.

Fixing the world with startups requires fixing who and how things are funded. I have argued, at length, multiple times, that VCs pouring more money into SaaS/consumer internet has made us lose the soul of hacking at the heart of the industry. However, these choices are entirely economically rational. Software makes more money. It grows faster. The markets are bigger. So, logically, the services in information technology will attract most of the investment and it will continue until we make a change. Note: And it could be, if you believe as I believe, that AI will elevate the human condition, that this multi-decade effort of investing in the digital realm is justified with the launch of large language models.

To emphasize, I think intelligent regulation is an absolute necessity for a just society. The only reason my great-grandmother had the electricity to power the lightbulb by which my dad could see his bath in a bucket was through FDR’s New Deal and the Rural Electrification Act. But these past few years have really made me doubt the ability of politicians to get anything meaningful done anymore.

Technology and science startups are this one remaining, desperate, “grasping at straws” hope I have that things will improve. I fully acknowledge the harm that tech companies have done, but I still have to hope that science and technology will save us because I don’t have much belief in anything else these days.

Tech is our best path for lowering the cost of utilities and services. People need those things to survive, so making them cheaper is a moral necessity. 940M people globally do not have access to electricity—the infrastructure is too expensive, and they are too poor to afford it. 3B people do not have access to clean cooking fuels. You cannot simply regulate your way out of a problem of this scale. Governments will subsidize and nonprofits will donate, but my sense is that innovation is the way out of this. The only reason my great-grandma was able to afford plumbing was because it became cheap enough that even subsistence farmers could afford it.

New science and technology companies capable of deploying that science are what can save us. I find a deep amount of hope that the sectors receiving more funding lately (space, AI, robotics, climate tech, biotechnology) will make a material difference in the world, not just help us process B2B SaaS demands. We should still experiment with how startups are funded and who deploys that capital. We should still experiment with how research labs are structured. But in the meantime, we should build. What else can we do?

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.08.31_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!