Sponsored By: Heyday

In "The Opportunity in Productivity" Dan Shipper writes that he'd love to see more productivity apps think about how automatic hierarchies can be created to help us more frequently bump into the things we weren’t looking for but needed to see. Heyday is doing just that by building an AI-powered research assistant that automatically saves and resurfaces the content you visit when relevant.

The base of the Eiffel Tower is a strange place to have a panic attack. However, for 20-100 tourists a year, that is exactly what happens with “Paris Syndrome.” People afflicted with the malady suffer from a wide variety of symptoms all under the banner of mental distress. Paris’s majesty has been built up to such a degree that the real thing can’t/won’t match the baguette-filled paradise they hoped for and tourists’ brains break.

Nerds (like me) visiting Silicon Valley for the first time experience similar psychological distress. On the outside looking in, I imagined SF as this cyberpunk epicenter. A land of hackers building technology, innovating under neon lights. Instead, I found a lot of entitled millionaires with “We Believe In Science” signs in their front yards. The only building people were interested in was the building of wealth. All of this is totally fine! Just very different then what I had thought it would be.

And if you think about it, it is kind of weird that Silicon Valley exists at all, regardless of its lack of Bladerunner aesthetic. There are a lot of other places that probably should’ve been the center of the tech universe. Boston had better universities and more government contracts. New York was and is the financial center of the world. The oft-cited catalyst of hippie culture existed in places besides Northern California.

The question of Silicon Valley’s existence borders upon the spiritual. It is a region that has birthed nearly every major technology development of the last 40 years. If you believe, as I do, that technology must jump radically forward for the human race to survive, then learning what powered the Valley’s output is worth serious study.

The answer to the question, unfortunately, appears to be rich assholes.

To be more specific, the answer appears to be the variety of a-hole known as a venture capitalist.

That, at least, is the thesis of The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Making of the New Future by Sebastian Mallaby. Mallaby posits that it was a combination of semi-unique social variables (Stanford, Hippie Culture, etc) AND a network of risk-happy, early-stage financiers that catalyzed the region’s meteoric rise. These two factors together created a self-reinforcing network of virtuous capital where each successive generation of funder and funded imparted capital and wisdom to the up and coming cohort of builders.

To prove his case, he takes the reader to the very beginning of venture capital with the founding of, all the way through the Growth Equity madness of today.

Let me put it simply: this is the best book on Venture Capital ever written. I’ve read just about all of them and Mallaby’s is the first one to get it right.

What makes Mallaby’s treatise on the topic so exquisite isn’t the meticulous research or careful writing style. What makes the book great is it is the first to accurately capture the role of venture capitalists. Most books that try to answer this question fall into two camps. The first, typically written by industry participants, are over-aggrandized hagiographies whose goal is brazen brand building. The second, typically written by mainstream journalists, are sensationalized gotchas that over-exaggerate stories in pursuit of professional accolades. Mallaby deftly navigates between the extremes by giving accurate reporting of the people behind the industry, while simultaneously looking with a critical eye at all the industry’s flaws (which are many).

I am an unabashed fan of venture capital. The purpose of startups, of technology, is so exciting that I can’t help but get giddy about this sort of thing. I find a special joy in the industry pre-internet. Before the internet changed everything in the ‘90s, the industry was closer to the hacker land of my imagination. It was a cottage industry, full of eccentric nerds, not consumed by the purely digital, and more focused on the impact of new chips, new computers, and new science. When compared with many of the startups I have pitched to me now, all focused on selling reskinned excel sheets to have ever more esoteric markets, part of me longs for the industry of yesteryear.

Mallaby’s book finally allowed me to grok what happened—to understand where the soul of venture had gone.

Between a Rock and a Power Law Place

The best way to comprehend the present is to examine the past.

Every technology employee today has to express gratitude to one bad manager—William Shockley. The Nobel Prize winner was one of the first to set up shop in the Valley, and was famously callous to his employees. Eventually, 8 of his disgruntled employees, in the summer of 1956, couldn’t take it anymore and went looking for something better. Note: Every single good thing in my life has resulted from me escaping a terrible boss so there may be a grand pattern here. Get a good boss and your life will be fine, so go get a bad boss and you’ll become a millionaire!

Simultaneously, a young financier out of New York named Arthur Rock, was interested in deploying a new type of risk dollars, “adventure capital.” This name is much cooler than the lame name of venture capital that we use today but it was essentially the same thing. After fortune handed Rock an opportunity to meet the Traitorous 8, he convinced them to form a company of their own versus just going to work somewhere else. This new venture, Fairchild Semiconductor, had the early versions of 3 interrelated elements that would come to define the next 60 years of technology investing:

- Equity for Employees: Part of Rock’s initial pitch to the group of disgruntled employees was that they could have ownership in the new company. While it was common for founders to have some equity, other early practitioners of adventure capital took abhorrent amounts of equity in the startup, sometimes exceeding 80%. Rock was a strong believer in all eight founders getting to buy into the company and did his best to treat them right. While they made a relative pittance compared to the financiers, when Fairchild exited, each of these eight did quite well. Their payout at their stock sale two years later was $300K, 600x of what they had paid earlier. The equity simultaneously incentivized the Fairchild team to focus more on increasing the value of their holdings, allowing them to zoom past their more bookish competitors.

- Limited Scope Financing: This initial financing set a precedence of an investment vehicle that had a distinct legal structure. Rock put together the limited partners for this deal, convincing wealthy investors to put in capital, while allowing the management team to do their thing. Around the same time, there were other players trying to be a public venture firm (bad idea) or relying on government loans (even badder idea) to do VC investments. To be fair, Rock realized the structure for this deal was suboptimal. He had to pitch this one investment to over thirty potential LPs before he was able to get a yes. When he set up shop for real, he was the first to hit on the structure of a limited partnership where there was a set pool of capital that had an expiration date and a specific thesis.

- Power Law Outcomes: Liquidity for this deal was provided via private transaction but Mallaby estimated the outcomes if it had played out in a public setting.

“A reasonable price-earnings multiple for Fairchild Semiconductor would have been at the top of IBM’s range, around 50. These rough numbers imply that because earnings were running at about $2 million, semiconductor might have been worth $100 million…In return for risking an initial 1.4 million, in other words, the East Coast investors had secured a memorable bonanza. Noyce and his co-founders had worked flat out and earned a combined $2.4 million. The passive financier had walked off with forty times more than that.”

That is a drinks on me, slap ya momma silly type of return. Not bad at all for a ~2 year time period. It was one of the earliest examples of the power law. The subject has been covered numerous times in this column, so we will save the in-depth explanation. But in short, this is where a small % of outcomes drive a large amount of the returns. In a typical venture portfolio, this manifests as 1 or 2 or the 20 portfolio companies driving 100% of the returns.

Mallaby goes to incredible depth on how Rock would later solidify the portfolio management portion venture through investments in subsequent companies, but Fairchild proved how momentously large these outcomes could be. Rock would go on to lay out the theory in a speech in 1962, arguing that you need huge winners to “average out the goofs.”

This 3 part model, employee equity, scoped financing, and power law, came to define the entire industry.

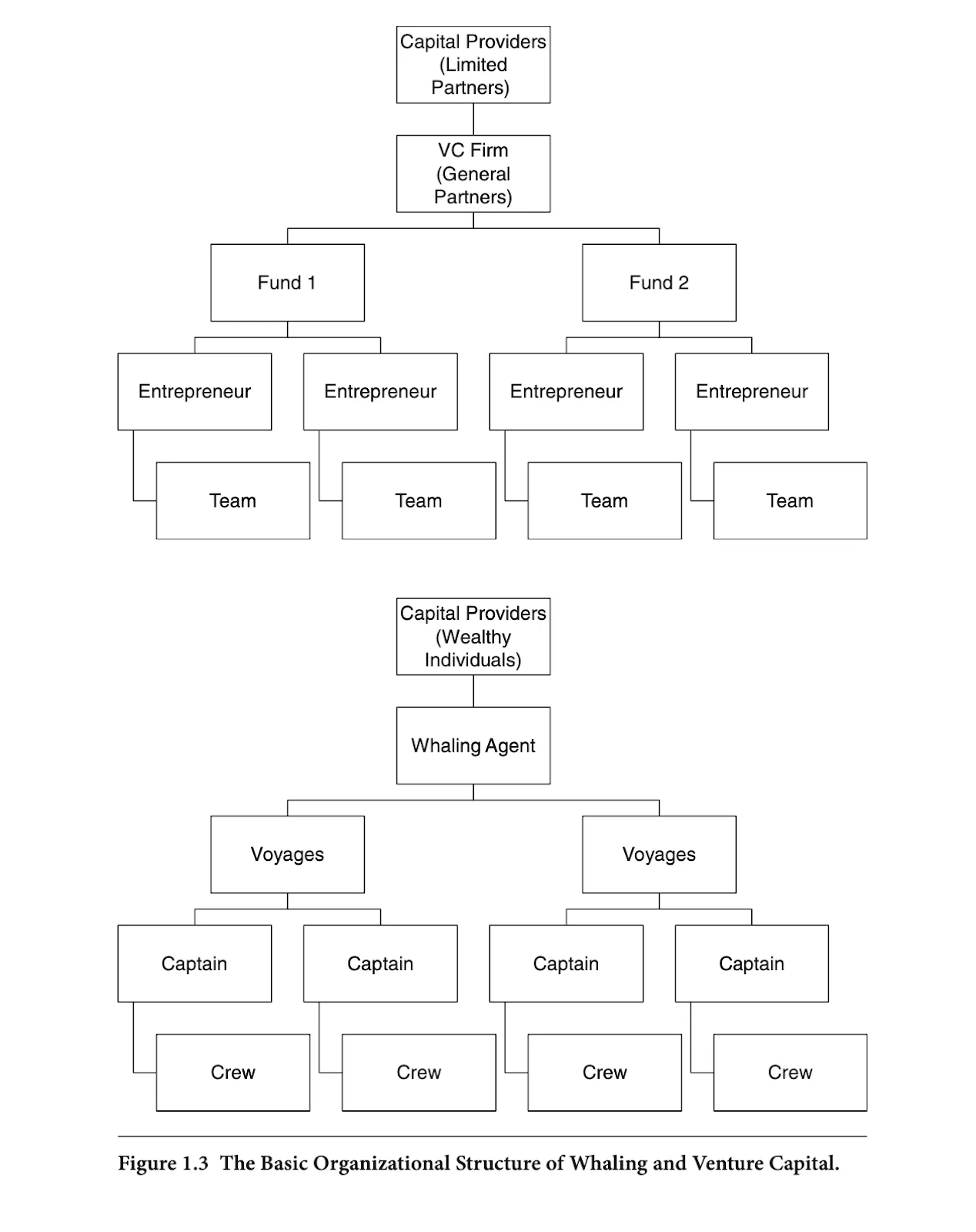

One intellectual diversion to note: I found it surprising that Mallaby chose to skip venture’s spiritual predecessor of the whaling industry. The three part model I just defined was identical in the 1800s whaling industry. The only thing I found curious was the exclusion of earlier, nearly identical financial models such as whaling in the 18th century. Limited partners gave a fund manager capital, the manager picked a captain, and while relatively few boats made money, those that did, did so fabulously. You can see the similarities between the two structures in the graphic below. The structure is basically a carbon copy from whaler to venture.

While it is true there is no evidence that Arthur Rock was influenced by these fishy forebears, I think it is important to note that this model of adventure capital was not wholly novel to the 1950s start of Silicon Valley. Mallaby’s subject is explicitly venture capitalists but I would’ve liked to see the whalers mentioned.Back to the subject matter at hand—Rock established these three norms and every investor since has seen how far they can push them.

Phases and Risks

When arguing why the venture capital industry has grown to encompass more and more startups in every sector, it is tempting to ascribe its success to more diversity of approaches. Starting in the ‘70s, further iterations of Rock’s founder-focused approach bloomed. Sutter Hills invented the “Qume model” of pairing technical talent with professional executives. Don Valentine of Sequoia Capital emotionally punched the founding team of Atari into submission, helping them build a business showing the value of an activist venture capital investor. Kleiner Perkins incubated companies in-house and moves beyond electronics to biotechnology with investing in Genentech. Modern day iterations like Y-Combinator pioneered accelerators and Tiger Global helped popularize the role of Growth equity.

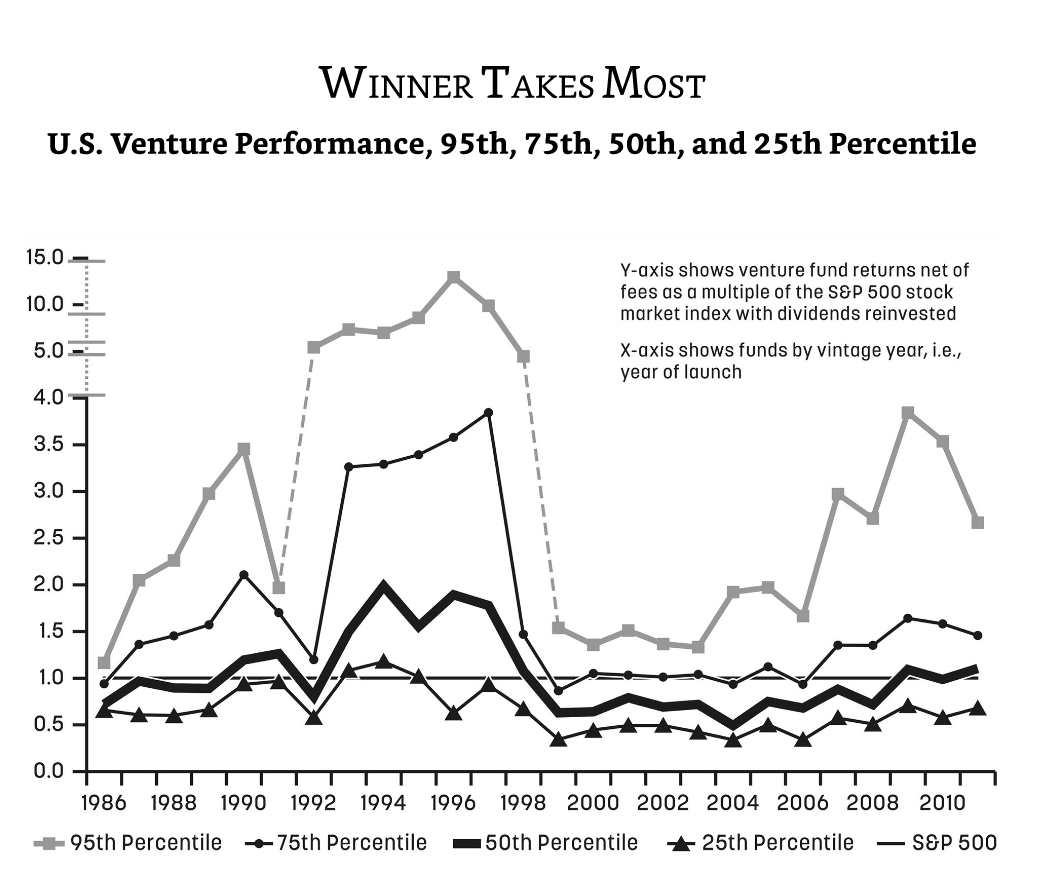

From doing it yourself, to telling founders what to do, to leaving founders entirely alone, all are housed within the venture capital model. Remarkably, all of these produced top quartile, market-beating returns. To me, this diversity of approach shows less the strength of venture as an industry but more the strength of the power law carrying their results.

Maybe the answer is technology waves?

At first glance, this argument also has merit. Moore’s law powering silicon chip improvements carried much of the 70s and 80s. The internet made the late 90s and 2000s. Smartphones and software as a service have powered the last 15 years. Each successive wave built off the previous, allowing more and more capital to be deployed successfully. However, this still doesn’t quite get it right for me. Other places had access to similar technology trends, but innovation stayed largely centered in California (with the notable exception of China which we are skipping for today. Mallaby does an incredible job covering the rise of China in the book, so if you are interested, you should really buy it!)

Instead, Mallaby arguments suggest that the paradigm by which we view venture capital must shift. Venture capital is a grand, wildly ambitious startup-capital network. Over the last 60 years, the industry has, in fund after fund, gotten better at maximizing IRR. The network in-aggregate is a self-optimizing machine that has found and funded the most promising startups, regardless of which version of venture capital would best serve them.

Note: Because the industry has well documented issues with racism and sexism it is demonstrably false that all worthy startups have been funded. However, essentially all meteoric technology success stories do involve the industry. There would likely be far more of these stories if the industry wasn’t solely staffed by white dudes who went to an Ivy.

When a network is optimizing an output, the results can get a little funky. With venture capital, Rock’s original goal was to liberate talented scientists and science from the burden of corporate America. However, because the success of that effort was measured via financial outcome, the deeper we got into the industry’s development the further we got from Rock’s vision.

An easy way to grok this is to consider what type of risk Venture Capital investors are willing to invest in. Startups are inherently a risky thing. It is hard to build things from scratch. A fund will want to have as many capital efficient, highly de-risked bets as possible. Simultaneously, a startup must be able to both de-risk itself AND be a massive business. The universe of companies that fit this description is exceedingly small.

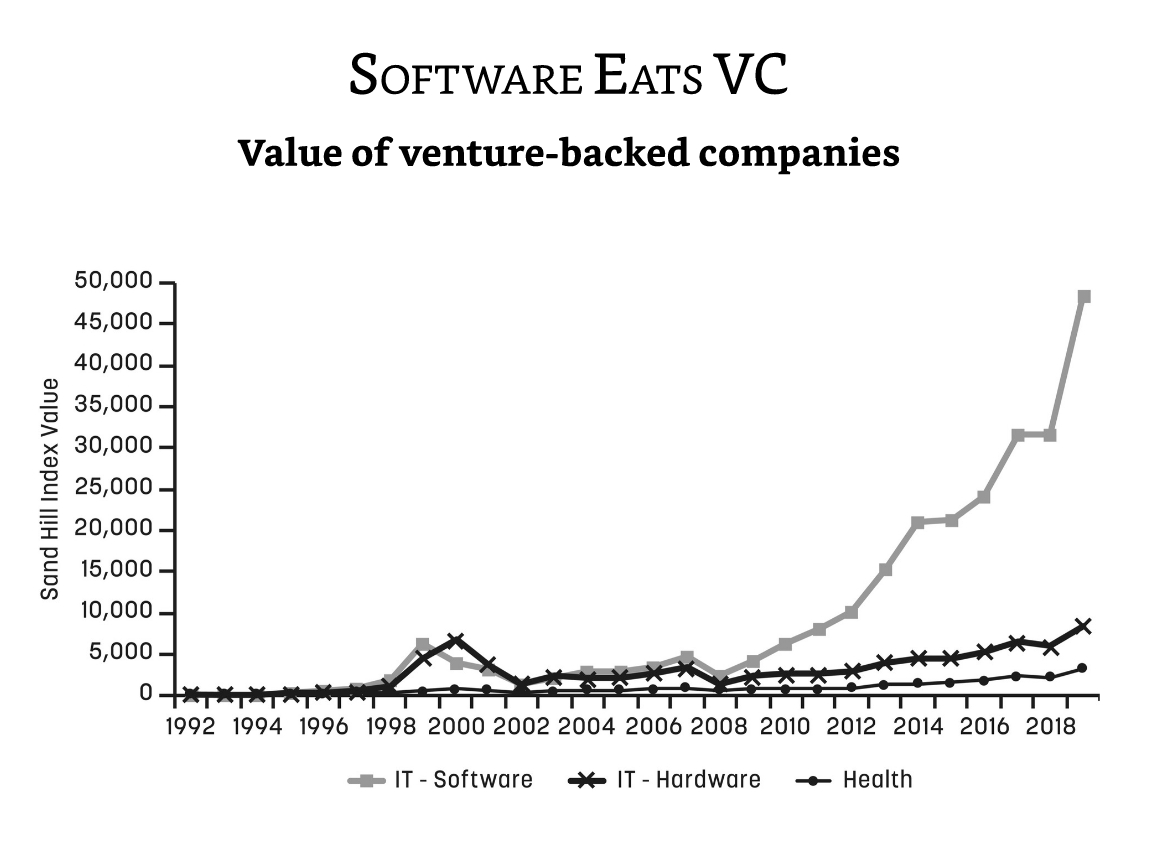

This means that a software startup, running an established playbook, that only needs a few hundred thousand to test its biggest risks, will be a much more tempting investment for a VC versus a biotechnology startup that is embracing scientific risk. It doesn’t mean these types of deep science, wildly speculative companies don’t get funded! However, the relative lack of risk in software eats up significant amounts of venture capital and diverts it from these moonshot bets.

Look, I love software, I invest in software, use software, make software. However, making more and more B2B apps is just not what the venture industry was meant for. Adventure capital does not describe a world where our brightest optimize task management tools. Essentially, the more predictable a model, the types of risk embrace moves it away from the spirit of adventure capital.

When I worry about the soul of venture, this is my exact concern. The pursuit of IRR kills the pursuit of improving of the human condition.

Stretching the Soul

In a perfectly efficient market, competition comes in and obliterates all profit. These markets require “a perfect, complete, costless, and instant transmission of information.” Part of the reason venture investing is like intellectual catnip for me is that it is the one market where secrets are encouraged. Because funds are private and the lifecycle is 10 years long, it takes a forever for competition to come in and obliterate prices. This means that for many years, venture investors bifurcated into the haves and the have nots:

Additionally, top brands like Sequoia have network effects where the winner begets winner, allowing them access to the top deals.

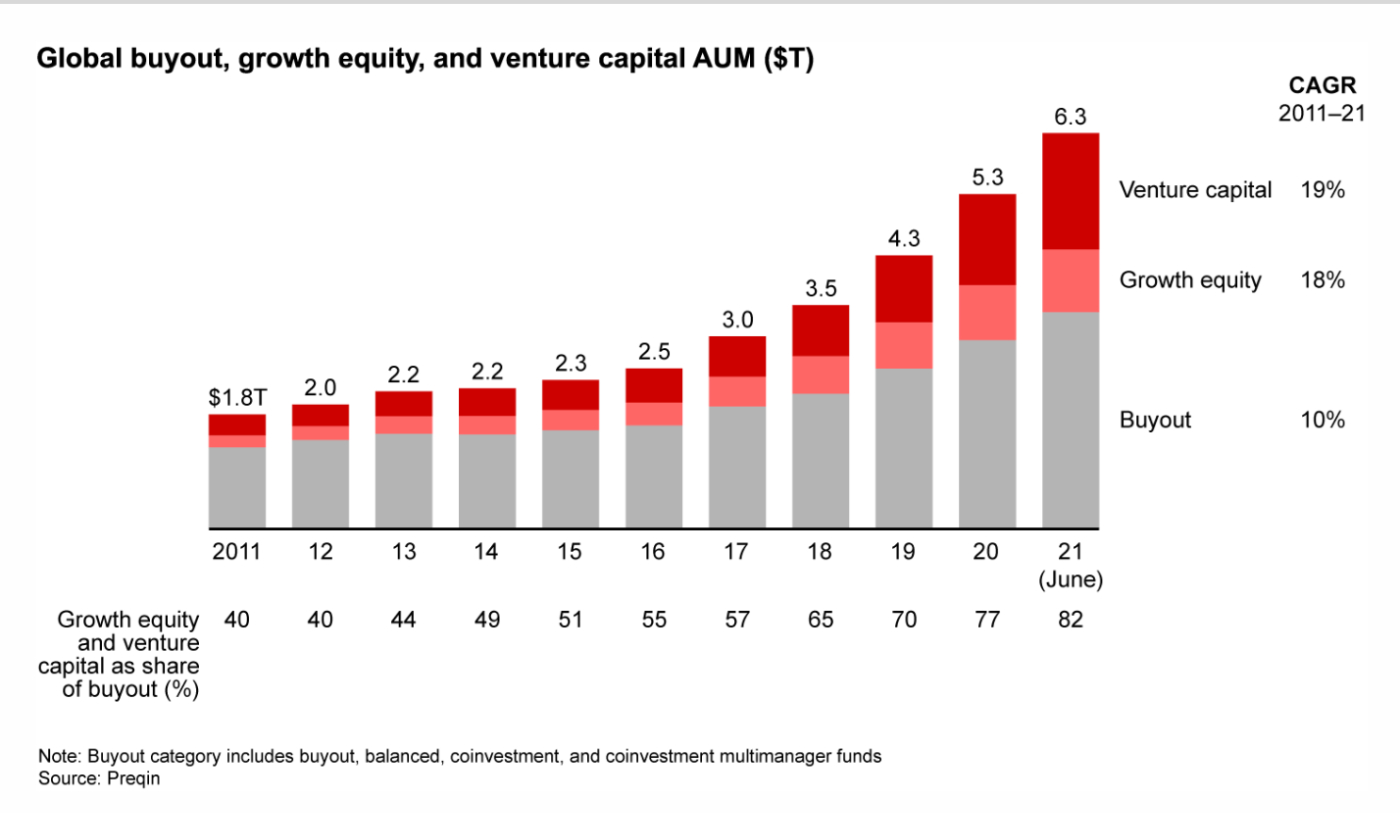

However, there has been an absolute explosion in the number of venture dollars over the last 10 years. This includes both traditional venture investing and the burgeoning field of growth equity.

This is bad for investors because excess capital raises prices and makes their jobs harder. There can only be so many people competing for software deals! At some point, maybe right now with the market crash, there will be no alpha left. All of this excess capital has to go somewhere and surely some of it will go to more compelling causes. Mallaby documents this phenomenon by focusing on Tiger Global, a crossover hedge fund that has become a major player over the last few years in the venture markets.

I have perspectives on where the venture markets go from here (surprise, I think writing is an important part of it) but that is beyond the scope of this piece. What matters is that if you care about startups, if you care about technology, you need to read this book. Mallaby will take you from the beginning of the industry and help you answer for yourself, how to save the soul of what we are trying to build.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!