TL;DR

- This is part 4 of our series exploring the income statement. Previously we have covered revenue, COGS, and gross margin. These are what help determine whether a company’s good is profitable.

- Today we are diving into the blurry, argumentative world of “other” expenses. These are the things that help you know whether the business supporting the product actually works. SG&A, Opex, EBITDA, none of these have universal meaning and are subject of contention among investors and operators.

- Understanding when/how to apply these terms will help you accurately price risk.

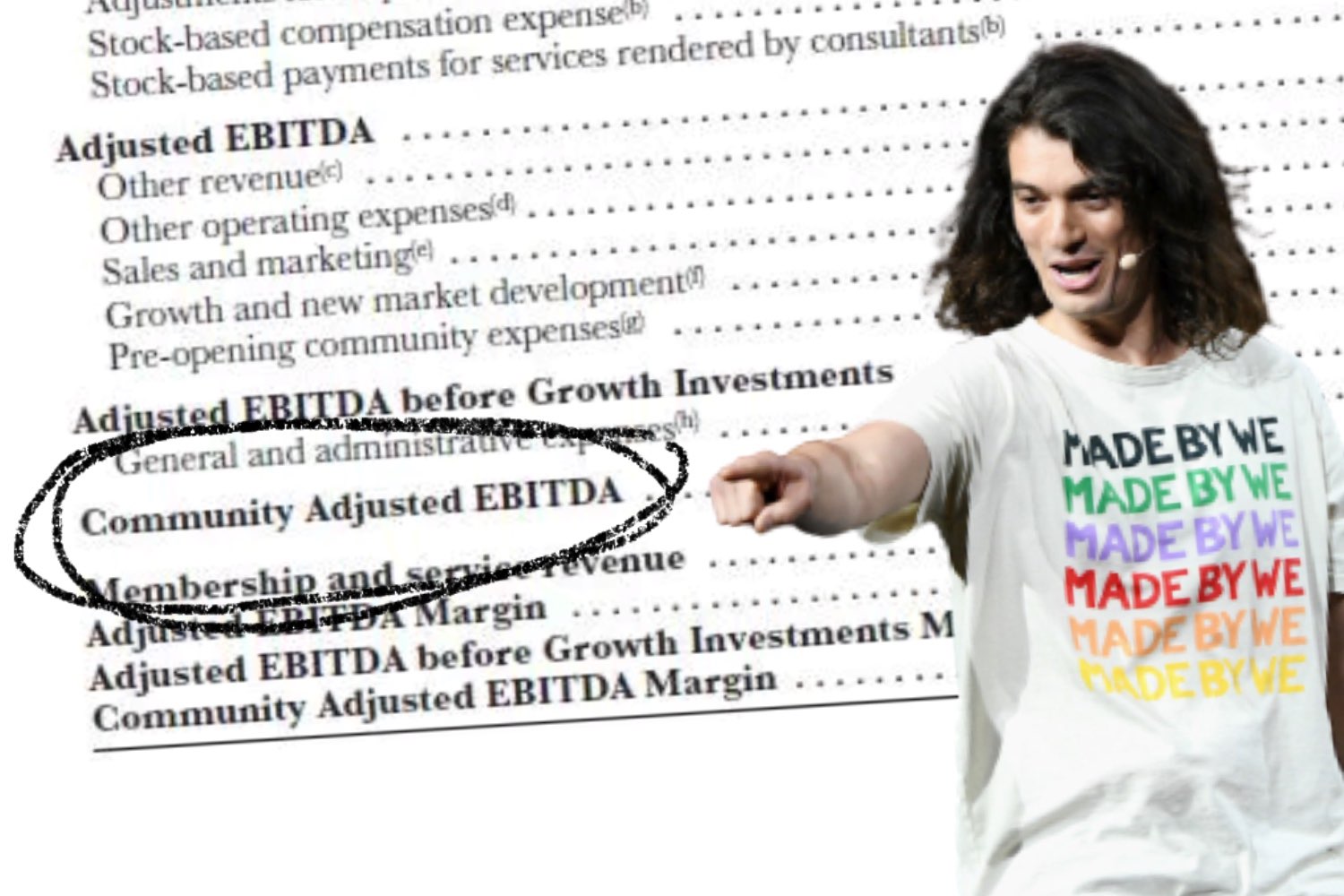

A tall, shaggy-haired Israeli strides across the stage. His every step is greeted with exuberant revelry by his adoring acolytes. They yell. They scream. They begin chanting his name. “Adam! Adam! ADAM!” This isn’t a war hero or local athlete with a championship trophy. Instead, this charismatic, barefooted fellow is Adam Nueman, the once-heralded messiah of real estate, the now-deposed king. He is best known as the co-founder of WeWork, the great Icarus of venture capital-fueled startups. WeWork would fly too close to the sun and burn—burn through mountains of Softbank’s funding to achieve a sky-high $47 Billion dollar valuation. His company would have its wings clipped by investors and would eventually fall back to the bloody, competitive ocean of private markets after their failed IPO. Along the way, they invented their own infamous financial metric, community-adjusted EBITDA, which will be the focal point of today’s article.

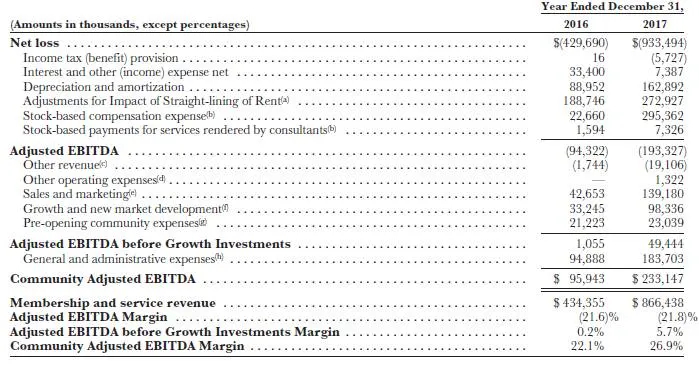

Originally proffered up in a bond vehicle, this metric was essentially the company’s attempt to say, “Hey look! Once we decide to flip a switch, each individual building is profitable.” To do so they “subtracted not only interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, but also basic expenses like marketing, general and administrative, and development and design costs.” If you feel like looking at it, here is the statement from the bond where this metric was introduced.

Essentially, Community Adjusted Ebitda was the amount of rent they collected from tenants minus the rent they had to pay to building owners. In a world where they had crazy low customer turnover, fired every staff member (including all the hard-partying executives) this number would come true! Easy peasy, lemon squeezy. Note: This is not lemon squeezy in the slightest.

As you can imagine, the talking heads had a field day. Some of my favorite titles included,

“The magic of adjustments: ebitla-dee-da”

“WeWork accounts for consciousness” (Matt Levine actually ends up taking a similar position to me on this one)

Even more recently, friend of Napkin Math, Packy at Not Boring called it, “quite possibly the dumbest f***ing financial metric in financial metric history.” Note: Edited for swears, this is a family-friendly financial publication. I know someone out there reads my writing aloud to put their children to sleep. As such, F bombs will not help said beleaguered parent’s cause. For you my fertile friend, I will keep this publication very boring.

But, heaven help me, Lord protect me, I think that this metric isn’t entirely bad. In fact, I think it may even be understandable and perhaps, just perhaps, community adjusted EBITDA may be a reasonable metric to use. While I am cringing at what vengeful nerds will say about that last sentence on message boards, I beg that you give me a little benefit of the doubt. You have trusted me as we discussed revenue, COGS, and gross margin, I ask that you trust me a little more as we discuss the weird, wacky world of expenses and earnings.

Today is a continuation of our series on the income statement. If you would like to subscribe to future financial concept explainers and unlock my previous writing you can subscribe below with 3 clicks.

But before I can burn all my credibility by defending WeWork’s funky finance, we need to start with the basics.

What are costs and earnings anyway?

In previous articles, we discussed how when you run a business you usually would like to make money. Shocker!

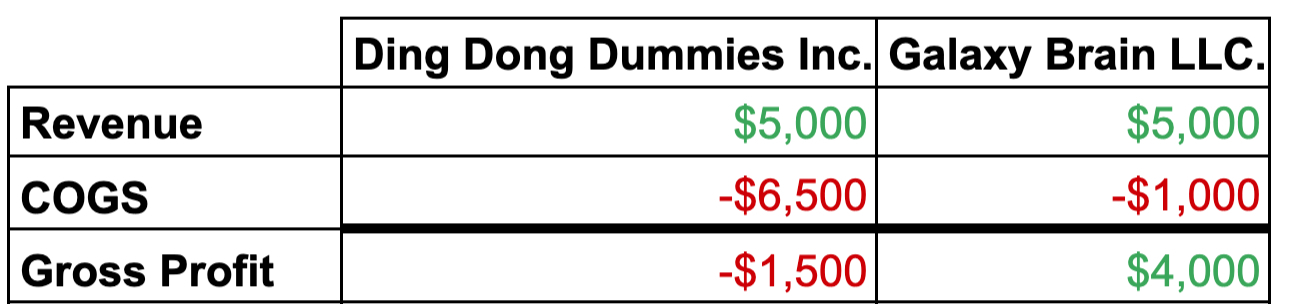

To do that, you have to do two things. One, you need to make money for the things you sell. This is your gross profit. It is the money you make selling your product (gross revenue) minus the direct cost to make each product (COGS, aka Cost of Goods Sold).

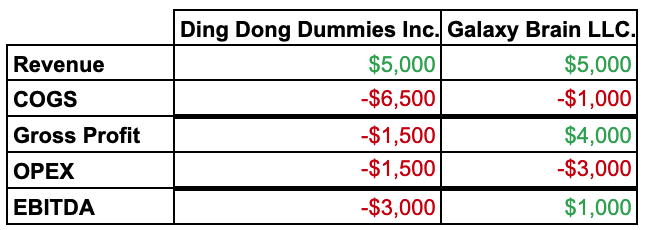

Above is our canonical example of Ding Dong Dummies vs Galaxy Brain LLC. DDD sells doorbells, Galaxy Brain sells productivity software.

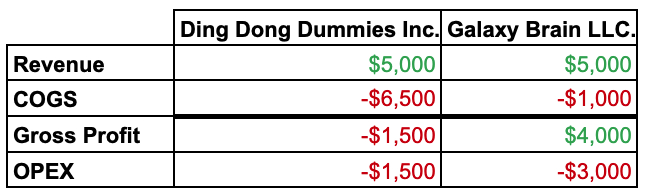

The second thing you need to make sure is there is enough gross profit left over to cover all the rest of the costs involved in running the businesses. For instance, a business that sells doorbells does not only consist of the doorbells to be sold. It also consists of the salespeople (and their squat racks they primarily use for bicep curls), the doorbell engineers (and their mission critical free lunches), the executives (and the corporate jet they say is standard in their line of work). All of these are costs that are (supposedly) a necessity to sell the product.

What makes these costs different is that they are indirect costs of making the company’s good. While I’m being facetious in how I’m describing these functions, they do matter and the cost is necessary. These types of expenses are usually cash costs. Salaries, R&D, marketing, admin, these all cost cash in the time frame that the income statement is prepared. Typically this is called Operating Expenses (OPEX).

For our example, DDD would not include the hardware components that go into a doorbell (those are included in COGS) but they would include the marketing it took to convince you to buy it. Galaxy Brain would consider their server costs COGS but their executive admin OPEX.

You will often hear the term SG&A (sales, general, and administrative) expenses when discussing this second category of costs. This can mean the same thing. Unfortunately, this is a matter of theology rather than science. They may mean the same thing but if you ever see them broken apart, OPEX will be the broad category with SG&A held underneath it.

Where it gets complicated are the non-cash costs. These are the things that are technically costs, but they aren’t actually cash. Depreciation, Amortization, a bunch of boring looking words that I will cover in a week or two. What matters for today’s purpose is that companies don’t actually like talking about these non-cash costs. They would much rather you ignore their costs (because more costs are apparently...bad for business? Idk) and thus the infamous EBITDA was born.

EBITDA stands for earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. We will cover these terms in our next post but for now know that because they have less immediate implications on a company’s cash, some analyst’s will argue that they can be safely ignored. Somehow the analysts who push this narrative are always the ones whose compensation is tied to you purchasing their stock pick. Weird!

So to summarize before we get back to WeWork’s shenanigans: OPEX stuff is the semi-immediate cash drains on the business. In case there are several broken out categories of SG&A, you’ll typically see companies compared on an EBITDA basis. Whew, we did it! You now know finance.

So now that you’ve invested all this time and intellectual capital into this topic you should probably be asking...

Is any of this stuff actually useful?

Warren Buffet is the Oracle of Omaha, one of the savviest and most financially grounded investors of all time.

He also happens to hate EBITDA. (And you have to imagine he really hated WeWork’s spicy version of it).

“It amazes me how widespread the use of EBITDA has become. People try to dress up financial statements with it.

We won’t buy into companies where someone’s talking about EBITDA. If you look at all companies, and split them into companies that use EBITDA as a metric and those that don’t, I suspect you’ll find a lot more fraud in the former group. Look at companies like Wal-Mart, GE and Microsoft — they’ll never use EBITDA in their annual report.

People who use EBITDA are either trying to con you or they’re conning themselves. Telecoms, for example, spend every dime that’s coming in. Interest and taxes are real costs.”

His business partner, Charlie Munger, summarized their viewpoint more succinctly,

“I think that every time you see the word EBITDA [earnings], you should substitute the word ‘bullsh**’ earnings.”

They highlight the tension that is inherent in all financial reporting—you would be better off if you lied. You wouldn’t be better from an ethical view, or from a “I don’t want to go to jail” sort of way, but lying on public financial documents will (in the short run) be advantageous to a business. This is fake it till you make it on the scale of the New York Stock Exchange.

The narrative driving a business can be shaped by many things. Elon Musk tweeting memes and smoking pot with Joe Rogan is (somehow) good for Tesla! General Motors using analyst days and investor presentations to convince everyone that autonomous vehicles are close at hand (despite the technology being years away) is good for GM! In a sociopathic way, financial documents can be viewed by unscrupulous management teams as an additional tool to shape their company’s narrative.

For U.S.-based businesses, there are legal standards called General Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) that businesses must hold to. These legal hurdles insert a level of trust into the market (which is partially why some companies, particularly Saudi and Chinese ones that have *cough* questionable financial statements, have hesitancy about listing their stock in the U.S.) but it isn’t foolproof. There are always edge cases where the laws weren’t written to account for dastardly financial machinations. You’ll hear this called “earnings management” and it is usually toeing the line of legality. Note: There is no company that practiced this with such brazenness as GE. It went well for 20 years but eventually caught up with them in 2009.

Earnings management and narrative deception happen frequently in OPEX and EBITDA. This stuff is just a lot murkier than Gross Margin! Thus, Warren Buffet’s distaste for it.

This brings us full circle to WeWork and Community Adjusted EBITDA. If EBITDA is questionable and narrative manipulation is ethically dubious, how can I feel not totally repulsed by what WeWork did?

WeWork and GAAP’s failure

In their initial financial offerings, WeWork described Community Adjusted EBITDA as follows,

“Community Adjusted Ebitda is core platform revenue (i) less excess customer incentives, (ii) less supplier referrals, (iii) excluding the impact of legal, tax, and regulatory reserves and settlements recorded as contra-revenue, and (iv) excluding the impact of our 2018 divested operations. We believe that Community Adjusted EBITDA is informative of our Core Platform top line performance.”

Actually, my mistake - that was actually from Uber’s S1 as they defined their own metric that showed the profitability of their core product.

“Core Platform Adjusted Net Revenue. We define Core Platform Adjusted Net Revenue as Core Platform revenue (i) less excess Driver incentives, (ii) less Driver referrals, (iii) excluding the impact of legal, tax, and regulatory reserves and settlements recorded as contra-revenue, and (iv) excluding the impact of our 2018 Divested Operations. We believe that Core Platform Adjusted Net Revenue is informative of our Core Platform top line performance because it measures the total net financial activity generated by our Core Platform after taking into account all Driver and restaurant earnings, Driver incentives, and Driver referrals…”

It goes on from there but you get the idea.

My (admittedly heavy-handed) point here is that all businesses need to use self-generated metrics that are outside of the scope of generally acceptable accounting principles. Every firm, no matter whether it is in social media or real estate or software, can be more thoroughly understood than the generic “Sales, General & Administrative” row on an income statement. The broad standardization of all financial documents allows for some inter-firm comparability but it is a surface level knowledge. You must have detailed, nuanced metrics that give you more fine-grained segmentation of where costs come from to truly price the risk inherent whenever you invest.

The issue is not that these metrics exist. Rather, it is the complete lack of accountability on them. Firms have complete control over what they are called, how they are defined, and when they are shared with investors. Something looks bad? Quit sharing it. Want to scare competitors? Talk about it!

Note: This last one was AWS’s strategy. I remember when they first started breaking out their AWS versus Amazon earnings and I was chatting with people competing against AWS. There were accounts of CEOs/investors of competitors literally vomiting in fear. If your financial performance is so strong you make rivals nauseous you are doing it right.

WeWork’s community adjusted EBITDA was the penultimate form of financial self-expression. Their intent—to show that there is a version of reality where each building is profitable—is totally reasonable! As an investor, you need to know that and you could never find that out with standard income statement metrics. The issue, and really the issue with WeWork as a whole, was that the CEO was so out of control that he thought he could get away with anything. Community Adjusted EBITDA sounds a whole lot sexier than core unit economics. I really do think that if they had just changed the name from something so grandiose it would’ve been fine. Sure, it would’ve raised some eyebrows, but it would’ve been totally par for the course for a high-growth startup!

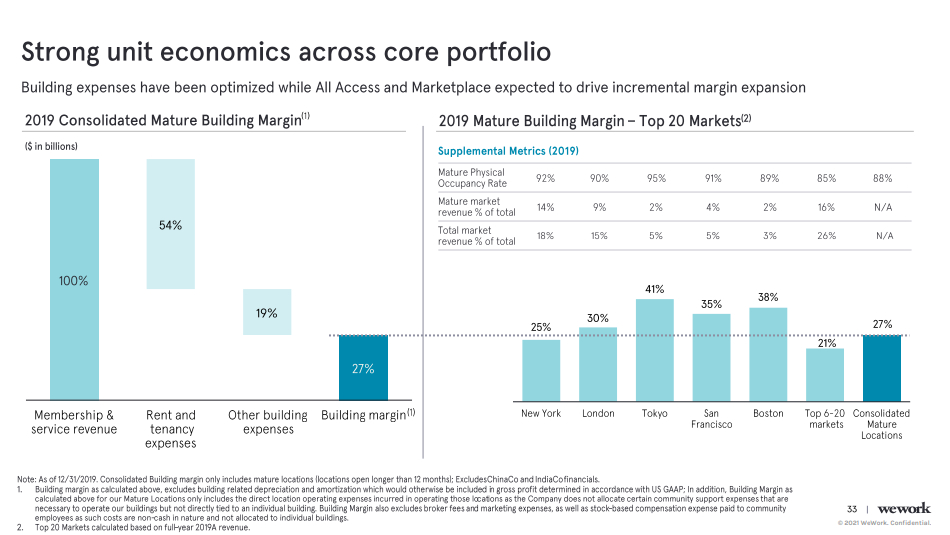

As proof, all we have to do is check out WeWork’s upcoming SPAC presentation. While the word “community-adjusted” never appears, this exact job to be done, namely showing unit economics, is covered in extreme detail.

Mature Building Margin isn’t a carbon copy of community adjusted EBITDA, but the goal is the same.

If Adam had any sort of board oversight or a CFO who was telling him that the metric name was dumb, then this probably would’ve gone off without a hitch.

Recap

- OPEX is the cost for the things supporting the sale of your product. Things in this category will typically have more immediate cash requirements.

- EBITDA is made up, but so is all finance, and can be useful if used carefully

- WeWork made some really stupid decisions. Community Adjusted EBITDA was one of them but it is understandable. With a different name, it probably would’ve been fine.

If you would like to receive financial and business explainers like this in your inbox, hit subscribe below.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.08.31_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Almost feels like community adjusted ebitda is closer to gross margin than anything.