Sponsored By: Brave

This essay is brought to you by Brave, the web browser that makes the internet ad-free (even on Youtube). It's faster than Chrome and more private than Safari, plus it works with your favorite extensions.

Amazon and Berkshire Hathaway are in the midst of an identical, potentially fatal crisis: They are simply too successful.

Buying Amazon stock is a bet on overworked managers screaming at their employees about customer obsession. Buying Berkshire Hathaway stock is a bet on an old geezer who likes peanut brittle. It is new America, one of silicon and servers, versus old America, a nation of steel and Coke syrup.

The two companies pursue wholly different capital allocation strategies. Amazon is constantly running hundreds of experiments at once. Berkshire mostly does highly concentrated buyouts or public equity purchases.

Amazon is the 5th most valuable company in the world at $1.069T valuation, and Berkshire Hathaway is the 6th most valuable at $717B. They are also revenue giants, with Amazon pulling in $513B and Berkshire doing $234B in 2022. At this valuation and revenue size, there are very, very few opportunities available to meaningfully grow the business.

While it’s a wonderful problem to have, it is a crisis nonetheless. Amazon has flailed into all sorts of large capital expenditures from movie studios (an $8.5B purchase of MGM) to internet satellites ($10B in expected capital spend) to healthcare (a $3.9B purchase of OneMedical). Berkshire Hathaway’s big move this year was getting majority ownership in a gas station chain ($11B, Pilot).

While the scale is unprecedented, this is something all companies face at some point in their existence. I call it the scaled out problem: growth plateaus for a particular business line as the marginal cost to acquire additional customers outstrips their lifetime value. Companies have to diversify their markets and/or product mix. If they don’t, they embrace a slow death by decay.

Tired of the creepy ads stalking you around the Web? Say hello to the Brave Browser, your new privacy superhero (cape not included).

Brave blocks all those annoying ads and trackers so you can surf in peace, even on YouTube. It's faster than Chrome and more private than Safari, plus it works with your favorite extensions. And did we mention it saves mobile data, battery life, and zips through page loads?

Brave makes the Web ad-free so, what are you waiting for? In just 60 seconds, you can switch and start browsing privately.

This conundrum can manifest on the scale of yeeting $10B dollars into satellites, or it can be as simple as a local diner adding a new menu item. However, by examining this problem in its most scaled, most extreme version (i.e., Amazon and Berkshire Hathaway), there are truths about investing and operating to be teased out that apply to everyone.

I think 99% of strategy advice is terrible. Having founders follow the latest Harvard Business School theory is like telling someone with a bipolar disorder to heal themselves by reading fortune cookies. Sure, there is nice stuff contained therein, but it is so generic that it is essentially useless. Every person and every business is unique—decisions have to be made in context. The goal for today is to help founders and investors make more informed choices, not give a recipe for success.

Amazon’s flywheel(s)

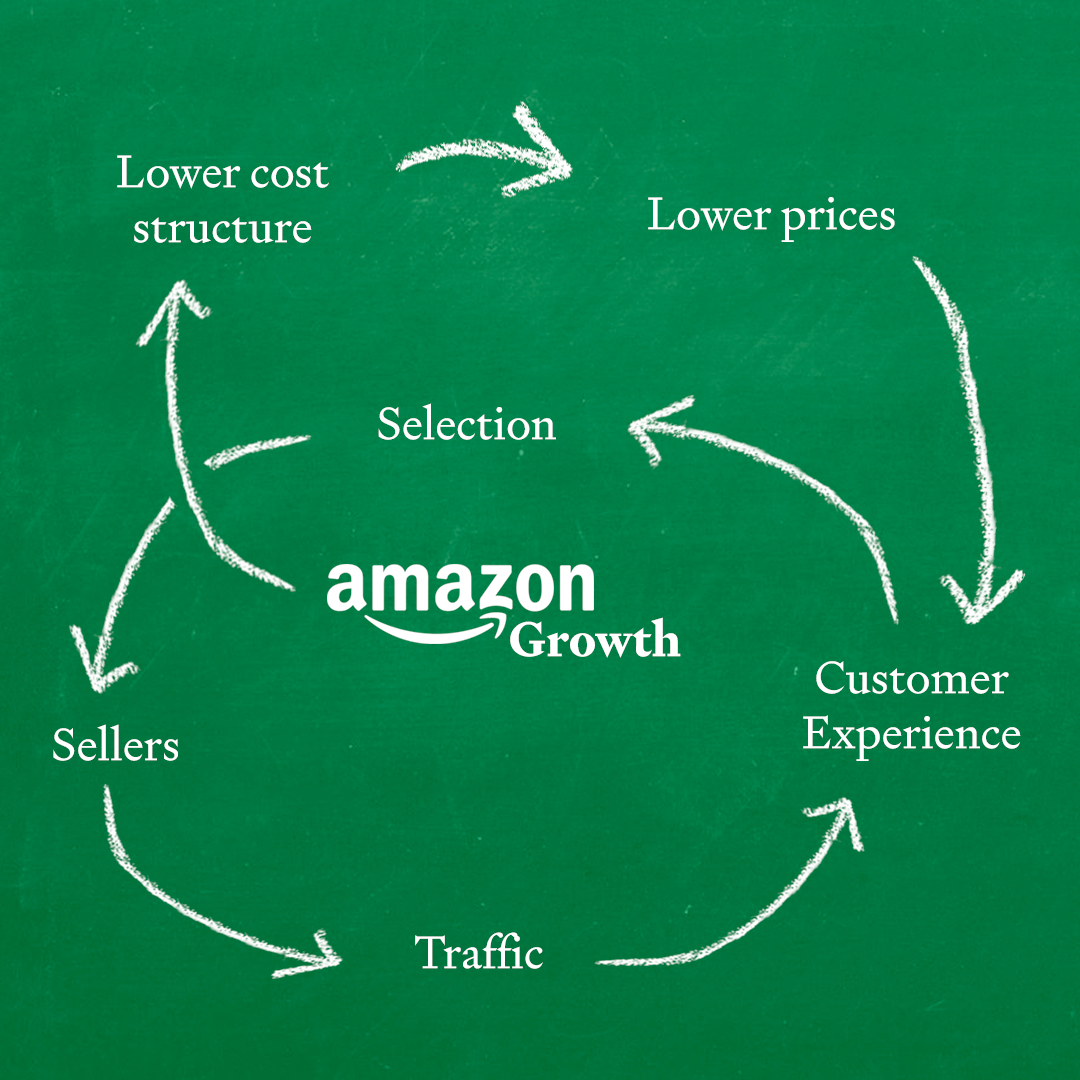

Amazon’s flywheel is this: The bigger Amazon gets, the more consumers and suppliers they have, which means they can get ever lower prices and ever better selection.

Amazon’s target market is all consumer retail spending, a $8T+ annual category in the U.S. alone. While it started with books, the vision was always to be “the everything store.” The initial expansion was incredibly simple. They went from books to other forms of media to kid’s toys—products that were pretty similar to one another. At the beating heart of this is Amazon’s flywheel:

However, as it expanded to more and more categories, Amazon found that not all consumer packaged goods are created equal. I had a conversation with a strategy lead at Walmart about e-commerce category expansion eight years ago, and he spent an hour complaining about “toilet paper and its shitty economics.” TP is bulky, consumers are sensitive about the price, and they are relatively cheap. Getting the last mile delivery profitable was near impossible for Walmart at the time. There are dozens, if not hundreds, of problems like this in the path to becoming the everything store: goods that at first glance look good, but end up being far less profitable then the initial customer/product fit of something such as books. Expansion means additional dollars of revenue become harder and harder to acquire.

Think of it this way: A company is powered by a flywheel, but the longer that flywheel spins, the less efficient the motion. Eventually the sand gets in the gears, and each additional unit of speed is harder to gain, and you have to add new flywheels to get the machine moving again.

It is important to note that this challenge began early for Amazon. Amazon’s category expansion was already hard by 2003 when the company started work on AWS. It was with the 2005 launch of Amazon Prime and the 2006 launch of AWS that the company successfully expanded what it was doing. It turned out these were enormously successful bets! It shifted the product and flywheel of the company from that of the best retailer in the world to being the culture of innovation in the world. It shifted the CEO job to that of pure asset allocation.

Berkshire’s flywheels

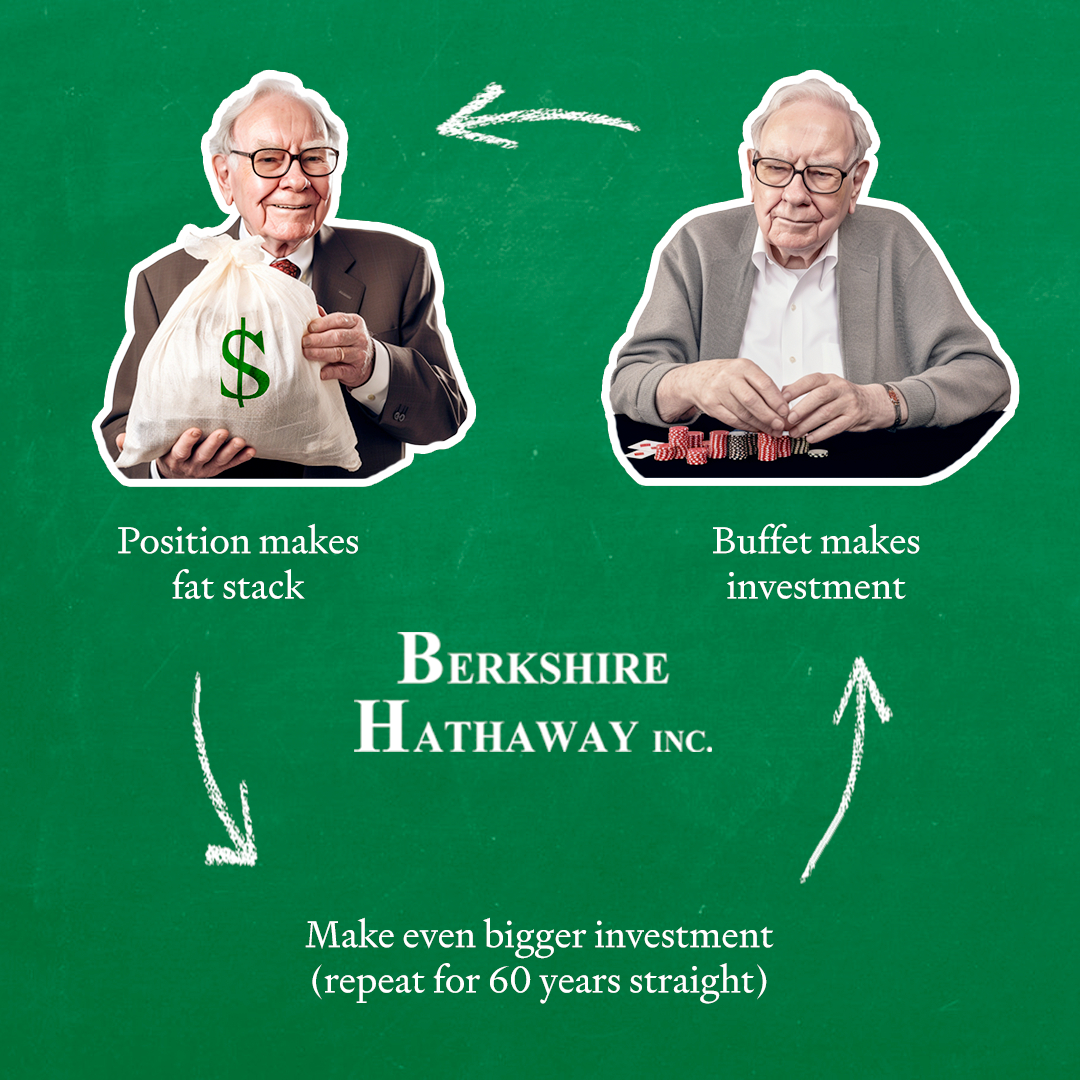

For Buffett/Berkshire, the flywheel looks a little different. It is basically this: Make money, lots of it, and keep giving it back to the guy who made it to see if he can do it again.

There is more complexity to this, but there also kind of isn’t. Berkshire Hathaway (BH) is a hedge fund with a very, very unique strategy that also happens to be publicly traded. Its playbook has shifted multiple times over the years, but right now it looks something like this: It operates a bunch of boring businesses (gas stations, insurance, etc.) and uses the excess cash from those companies to buy a mix of public and private equities. Sometimes it will also buy companies outright to add to the stable of high cash-flow businesses.

I had a finance mentor once tell me that “only one person gets the investing edge of being the smartest man alive.” You could make a pretty good argument that that person is Warren Buffett. And if you did happen to have the smartest guy alive running the ship, a pretty intelligent strategy would be “just do your thing, dude.” When the product is “old geezer think good,” a company can only scale as far as he can. Buffett is remarkable because he went further than anyone else in human history, but he is still human (and 92).

To get a sense of the difference in scale Berkshire has gone through it’s useful to compare two of its best positions. In 1972, Berkshire Hathaway bought See’s Candies for $25M. In 2019, the company did pretax revenue of roughly $2B. This is an incredible outcome. Two billion for some midtier chocolates is not shabby. However, this incredibly scaled, profitable business only contributes .85% of revenue for Berkshire. To get a 10% growth rate out of similar investments now, Berkshire needs to acquire 11.7 See’s Candies every single year. This is kind of hard to do!

In contrast, Berkshire’s largest public equity position is Apple. From 2016–2019, Berkshire Hathaway acquired about $36B worth of shares in the company. Those shares are now worth over $110B. While it’s not the highest IRR Buffett has ever achieved with an investment, in terms of absolute dollars returned, this will go down as one of the greatest investments of the past 100 years.

But there is only one Apple! There are only so many stocks that can do this for you. And there is only one Buffett.

The firm started diversifying its leadership team in 2010 with the hiring of various senior operators and investors, but it is still tough to see how the company gets much bigger. Adding additional flywheels, in the case of Berkshire, means adding additional people who can intelligently deploy capital. And they still have to be able to find positions that are big enough to move the needle for the company.

Abstracting the scaled-out problem

A gross oversimplification of a company’s life cycle would be something like this:

- A company makes a successful product that gets it stupid rich.

- The company builds or acquires nearby opportunities with excess cash as its core market’s growth starts to run out.

- Repeat ad nauseum, spreading the company further and further afield.

- Eventually, the company is holding a grab bag of uncorrelated assets that underperform.

When it comes down to it, company success is the ability of a CEO to make the right investment decisions. For a startup, it might be building Feature A or B. For Amazon, it is whether to buy Whole Foods or MGM. But fundamentally, we are talking about the same calculation—return on invested capital (ROIC).

In the life cycle I describe above, the company only dies if the uncorrelated assets underperform. What made Berkshire so magical is that while the bets were only loosely related, it still did incredibly well. That’s the Buffett magic.

Theoretically, you could have a regular, non-hedge fund company of Amazon’s size with a random grab bag of garbage if the ROIC stayed the same. The income statement would still be calculated with the exact same formulas. It just turns out that is near impossible to do. Human beings are terrible, terrible, terrible at consistently deploying capital in an ROIC positive way.

In fact, Buffett made and won a $2M bet that, including fees, costs, and expenses, an S&P 500 index fund would outperform a hand-picked portfolio of hedge funds over 10 years. He made the bet in 2008 and won it in 2018. An actively managed portfolio will, statistically, perform worse over the long run.

This is why companies are always implored to “stay in their lanes” by their boards—their investment decisions are less about pure asset allocation and more about aligned capital deployments. All the strategy books imploring operators to build “synergies” are telling you to do so only because those synergies make it easier for the assets to be successful. For example, In Amazon’s retail business, the uniting force would be Amazon Prime. Having a consistent user identity and subscription allows all of Amazon’s consumer products to be tied together.

The closer you get to the questions of being a hedge fund, the more statistically unlikely it is for a company to outperform the S&P 500.

What makes Berkshire remarkable is that despite having a bunch of random junk, it all continues to perform (more or less). What makes Amazon remarkable is that it has, in the past, shown the ability to do innovative things that end up being hugely valuable.

So the natural question is how to fix this. How do you solve the scaled-out problem?

Solutions

If you decide to go for it, you could take the approach of Amazon (we empower thousands of people to do small experiments), or you could take the approach of Berkshire (we empower one old geezer to make large bets), but ultimately as a company it is a risky position. Ultimately, the lesson for all companies is that success can be a double-edged sword, and growth can come at a cost.

Ultimately, I’m not sure you should continually expand.

Part of the reason Berkshire’s bet on Apple's stock has been so performant is exactly because Apple realized that there wasn’t a good way to deploy its capital. Instead, it returned capital to shareholders in the form of stock buybacks and dividends. This is good! Probably the best fiscal outcome for a business is to spend to achieve monopoly position and then just sit there for decades returning capital to its shareholders.

However, top performers and executives usually have very little interest in protecting an asset. Usually CEOs want to aggressively grow a company so they can increase their comp and prestige. There ends up being a trade-off between talent and performance that is difficult to navigate. Good luck convincing a killer to be the steward of a slow decay.

To make this post go viral on Twitter, I should end it with a quippy application of this case study. But I can’t! And that’s the point! The companies took opposite approaches to solving the scaled-out problem (empower a culture versus empower an individual) and were both successful to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars. In the micro version of this, I have seen egalitarian startups thrive, but I’ve also seen cruel dictatorships outperform too.

That there is no clear answer is the point. Sometimes you need to bet on your team and sometimes you need to bet on yourself. But Berkshire and Amazon both make it clear: You need to know what you are betting on.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.08.31_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!