Sponsored By: Notion

6 months free of Notion with unlimited AI.

Now, you can access the limitless power of AI, right inside Notion, to build and scale your company and team with one tool.

Notion is used by thousands of startups around the world as their connected workspace for everything from engineering specs to new hire onboarding to fundraising. When applying, select Napkin Math in the drop-down partner list and enter code NapkinMathXNotion at the end of the form. Apply by March 1!

If you’ve spent enough time in startups, you’ve likely heard of the concept of the killer app: an application so good that people will buy new, unproven hardware just for the chance to use the software. It is a foundational idea for technology investors and operators that drives a whole host of investing and building activity. Everyone is on the hunt for the one use case so magical, so powerful that makes buying the device worth it.

People are hunting with particular fervor right now as two simultaneous technology revolutions—AI and the Apple Vision Pro—are underway. If a killer app emerges, it’ll determine who gains power in these platform shifts. And because our world is defined by tech companies, it will also determine who is going to have power in our society in the next decade.

But here’s the weird thing: The killer app, when it’s defined as a single app that drives new hardware adoption, is kinda, maybe, bullshit. In my research, there doesn’t appear to be a persistent pattern of this phenomenon. I’ve learned, instead, that whether a device will sell is just as much a question of hardware and developer ecosystem than that of killer application.

If we want to build, invest in, and analyze the winner of the next computing paradigm, we’ll have to reframe our thinking around something bigger than the killer app—something I call the killer utility theory. But to know where we need to go, we need to know where to start.

Where did the killer app come from?

Analysts have been wrestling with the killer app for nearly 40 years. In 1988, PC Week magazine coined the term “killer application” when it said, “Everybody has only one killer application. The secretary has a word processor. The manager has a spreadsheet." One year later, writer John C. Dorvak proposed in PC magazine that you couldn’t have a killer app without a fundamental improvement in the hardware: “All great new applications and their offspring derive from advances in the hardware technology of microcomputers, and nothing else. If there is no true advance in hardware technology, then no new applications emerge.”

This idea—in which the killer app is tightly coupled with new hardware capabilities—has been true in many instances:

- VisiCalc was a spreadsheet program that was compatible with the Apple II. When it was released in 1979, it was a smashing success, with customers spending $400 in 2022 dollars for the software and the equivalent to $8,000–$40,000 on the Apple II. Imagine software so good you would spend 10x on the device just to use it.

- Bloomberg Terminals and Bloomberg Professional Services are specialized computers and data services for finance professionals. A license costs $30,000, and the division covering these products pulls in around $10 billion a year.

- Gaming examples abound, ranging from Halo driving Microsoft Xbox sales to The Breath of the Wild moving units of the Nintendo Switch. Every generation of consoles will have something called a “system seller,” where the game is so good that people will spend money to access it.

So this type of killer app—software that drives hardware adoption—does exist, and it has emerged frequently enough to be labeled a consistent phenomenon. However, if you are going to bet your career or capital on this idea, it is important to understand its weaknesses. There is one crucial device that violates this rule—the most important consumer electronic device ever invented. How do we explain the iPhone?

Now, for a limited time, unlock six free months of Notion with unlimited AI usage. Transform how you build and scale your company and team with one powerful and comprehensive tool. Notion is trusted by thousands of startups around the globe as the go-to workspace for engineering specs, new hire onboarding, fundraising, and more. Remember to choose Napkin Math from the partner list when applying with code NapkinMathXNotion before March 1!

How does Apple violate the killer app theory?

When Steve Jobs launched the iPhone in 2007, he pitched it as “the best iPod we’ve ever made.” He also argued (incorrectly) that “the killer app is the phone.” Internet connectivity, the heart of the iPhone’s long-term success, was only mentioned about 30 minutes into the speech! And when it first came to market, it didn't even allow third-party apps. Jobs was sure that Apple could make better software than outside developers could. (Wrong.)

Even when he was finally convinced that the App Store should exist, it launched one year later with only 500 apps. By comparison, the Apple Vision Pro already has 1,000-plus native apps, just a few weeks after its release.

To figure out why people bought the iPhone, I read through old Reddit posts, blogs, and user forums. I tried to find an instance of someone identifying the iPhone’s killer app at launch. The answers were wide-ranging, from gaming apps to productivity use cases to even a flashlight app, but there wasn’t one consensus pick.

So how did the iPhone go on to dominate when it didn’t have any must-have apps to begin with? One argument is that it was the App Store itself that was the killer app. By making it easy to download and build apps, Apple made the iPhone a winner. But Apple itself contradicts this theory with its own devices.

When the Apple Watch was released in 2015, it had 3,500 apps. Not one of them was a hit—despite the device launching with more apps than the iPhone and with an App Store, and the porting over many of the existing apps from the iPhone ecosystem. It wasn’t until around the watch’s third generation that Apple was able to figure out that its primary use case was health and wellness, neither of which is really app-reliant. They’re more a function of sensors and design.

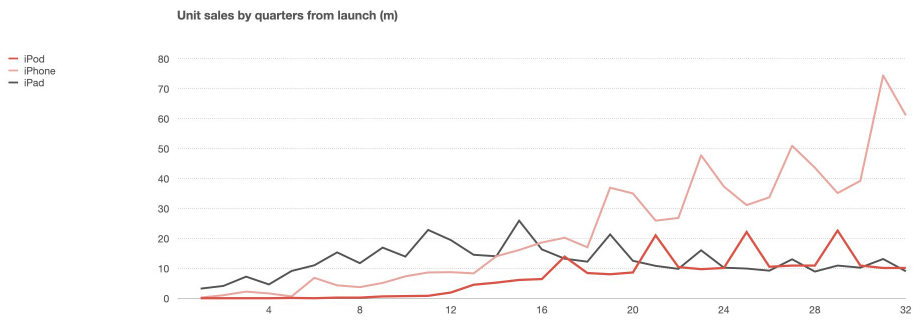

Shoot, pretty much all Apple devices start slow relative to the scale they eventually reach. It usually takes them 2–3 generations before sales start to soar.

Source: Benedict Evans.

Despite a total lack of singular killer apps, the iPhone and iPad have achieved enormous profits and scale. Even beyond Apple and the iPhone, this exception applies to many forms of personal computing, from desktops to laptops. Every year millions of laptops, cellphones, and tablets are sold without a killer app, even without the benefit of Apple’s App Store. How can this be?

Killer utility theory

To answer this question, I propose a new theory on the relationship between hardware and software. I call it the killer utility theory.

Killer utility theory argues that the more general-purpose a device, the less individual applications matter and the more important hardware differentiation becomes. It is the collective killer utility of all the apps that matter, not the existence of one killer app. Consumers buy an Xbox solely for gaming and, for many, solely for Halo (at least, that is what it was for me when I was 12). By contrast, we buy a laptop because we want to do our work, play games, message our families, and stream Netflix.

The theory itself isn’t necessarily novel. What matters are the second-order implications.

Because silicon chips are now cheap, powerful, and ubiquitous, every device has the computational horsepower to be a general-use platform. Laptops compete with tablets compete with VR headsets, all for the same set of consumers’ jobs to be done. The battleground has shifted from having the “killer app” to having the “killer utility.”

The more developers and unique sensors a hardware manufacturer has, the less reliance they have on a killer app. Competitive advantage stems from the ecosystem and novel hardware that developers use in unexpected ways.

The iPhone didn’t need a killer app because it simultaneously had:

Ecosystem: Apple had a devoted fan base of developers who were chomping at the bit to release apps on the newest device.

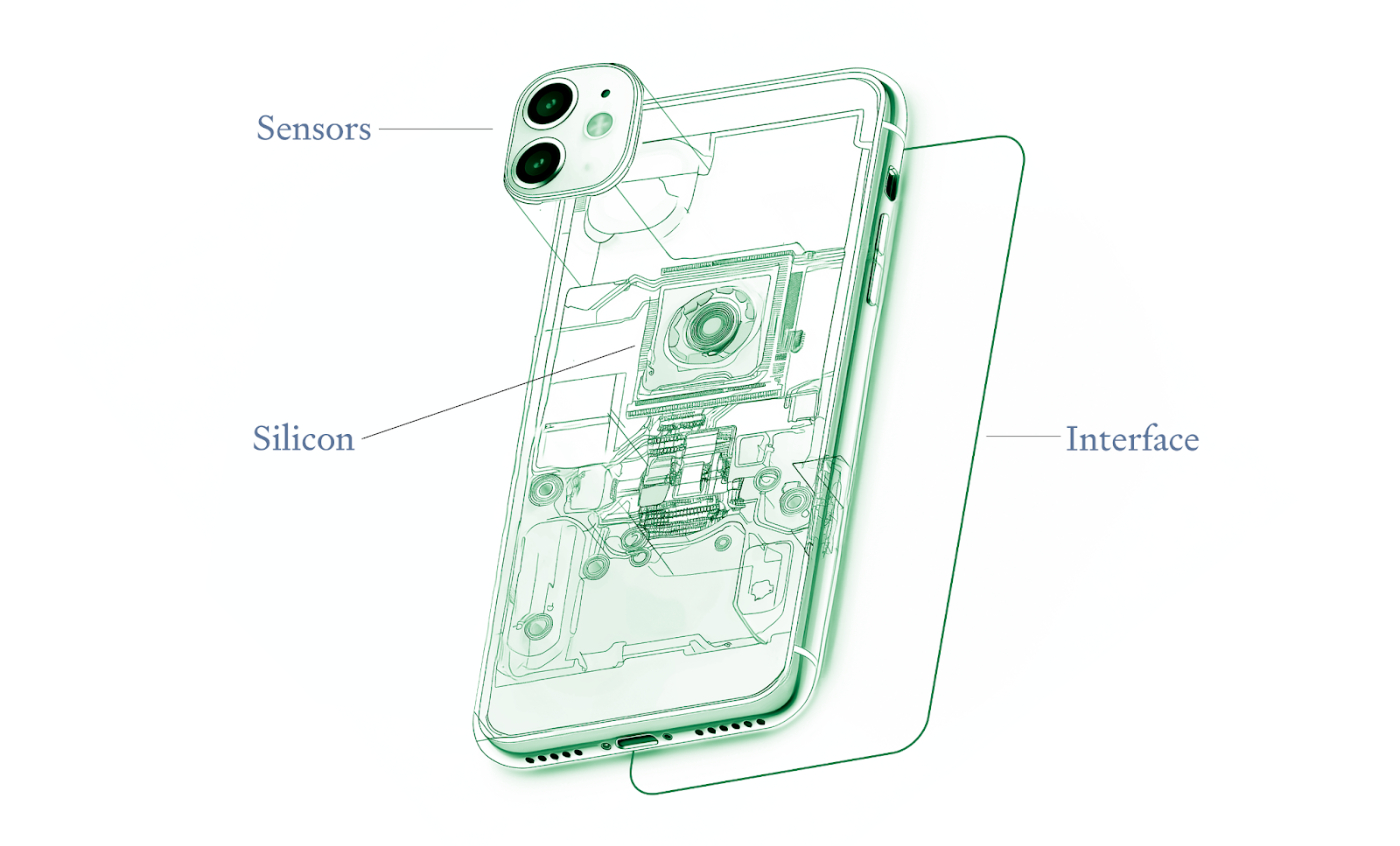

Novel hardware:

- Silicon: The original iPhone used a Samsung System on a Chip with a processor from ARM. It wasn’t quite custom—Apple wouldn’t go as far as using chips designed in-house until 2010, with the launch of the iPhone 4—but it was designed for the multi-touch use case.

- Interface: Multi-touch glass freed the first iPhone from the constraints of a keyboard. You could play games and send emails from one device without the clunkiness of a stylus or physicality of buttons.

- New sensors: The original iPhone was missing a ton of things we now take for granted. It wasn’t until the iPhone 3G in 2008 that GPS was implemented. While the original device had a rear camera (that wasn’t even capable of recording video), the front-facing camera wasn’t released until 2010, enabling applications like Snapchat, Zoom, and FaceTime.

Every illustration/Lucas Crespo.

The original iPhone was, in fact, a non-obvious winner—it wasn’t clear why it would be so successful. Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer criticized it, saying, “Five hundred dollars full-subsidized with a plan! I said that is the most expensive phone in the world and it doesn’t appeal to business customers because it doesn’t have a keyboard, which makes it not a very good email machine.” TechCrunch ran the headline, “We Predict the iPhone Will Bomb.” Both of these predictions cited the multi-touch screen as the reason the device would fail! I’m not trying to dunk on these folks—predicting the future is very hard—but they are indicative of the challenge of evaluating a new platform.

In their defense, they were sort of right: All the hardware and apps that came to define the iPhone, beyond the multi-touch surface, weren’t part of its first iteration. Steve Jobs’s ungodly powers of marketing, in combination with Apple’s developer base, was enough to get the iPhone ecosystem moving.

Some of the most useful apps weren’t made possible until subsequent generations of the iPhone. Uber needed the GPS, Snapchat the front-facing camera. Even the pedometer function so common in today’s health apps wasn’t possible until Apple included an accelerometer sensor in the iPhone 4.

Killer utility theory also better accounts for the strength of a hardware’s ecosystem than does killer app theory. A family of devices—like the iPhone, Mac, and Apple Watch—can share competitive advantages, depressing the margins of developers in their ecosystem. An app that could be a killer app for a single device, like Strava for the Apple Watch, is just one of millions in the iPhone ecosystem. This is part of the reason why Apple is able to demand such high fees from developers.

Apple doesn’t need a killer app for the Vision Pro because it already has dozens of them live on the iPhone. Inversely, most laptop manufacturers have relatively low margins because their ecosystem of developers can port their apps to any of their competitors.

Exclusivity is the key factor in killer apps. If an app relies on hardware that is only found on one device, then it has a higher chance of being a killer app. If it utilizes a novel form of human-computer interaction, like the iPhone’s multi-touch, it has a higher chance of being a killer app. The more exclusive hardware makers can make their ecosystem of developers such that they only want to develop for you, the less they need to have a killer app at all.

The Vision Pro and AI

The killer app has other weaknesses. For example, who is building the killer app for generative AI?

Is it Nvidia? Its chips and their associated firmware/software power all of the training runs that make large language models. The company’s revenue is up 265 percent year over year, at $22.1 billion.

Is it Microsoft and Amazon? Their cloud infrastructure coordinates the training runs happening on Nvidia chips. Microsoft is doing roughly $6 billion a year in Azure AI revenue.

Is it OpenAI? GPT4, which deploys on Microsoft servers on Nvidia chips, powers ChatGPT—an application that has surpassed a $2 billion revenue run rate. While most people would say that ChatGPT is the killer app, is the killer app the one that makes the least money?

Is it Salesforce? Its applications are powered by “OpenAI’s enterprise-grade ChatGPT technology.” In its earnings call last November, it said that “70 percent of the Fortune 100 are [Salesforce AI] customers.”

How are we to reckon with all of these companies growing the revenue of their AI products so quickly? Are they all killer apps, or are none of them?

Killer applications only make sense when a device is used for one thing, making it the wrong lens through which to view the two most important trends in tech today: generative AI and virtual reality.

Virtual reality is a generally applicable hardware computing platform, while artificial intelligence is a generally applicable software computing platform. Virtual reality devices and apps are reliant on a suite of sensors, screens, and silicon. Meanwhile, while AI is reliant on hardware to be deployed and trained, the parts of the application that depend on it are obfuscated away from the end user.

Killer utility theory would suggest that neither of these platform shifts hinge on building killer apps.

Instead, VR is a broadly applicable computing platform that is waiting for a sufficient quality of hardware to be sold. When we are trying to determine who will capture value in VR, we need to be asking if 1) the combination of speed, price, and utility allows for general computing tasks to be done better or 2) the VR hardware enables a totally new use case for computers.

AI is a horizontal software platform that can be applied to anything touching a keyboard. Asking for the killer app of AI is like asking for the killer app of WD40—it just makes everything run better. The “killer app” for AI will just be a regular old app that does something new or better with AI as part of that value proposition. Because AI is so economically valuable—for some time, at least—all participants in the supply chain will do well, from Nvidia to front-end applications.

As companies jockey for power with these new technologies, we have to ask who will maintain long-term exclusivity. In the case of VR, it appears to be Apple—for now. For AI, it is still unclear.

Evan Armstrong is the lead writer for Every, where he writes the Napkin Math column. You can follow him on X at @itsurboyevan and on LinkedIn, and Every on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

As much as I want to disagree, but it kinda make sense.

The intense competition among big companies prevents them from thriving and doesn't allow for the sharing of any kind of ecosystem