Sponsored by: Every

Work with the Every team to bring AI to your organization

We launched our consulting arm because we were constantly hearing from readers that while they wanted to implement AI throughout their operations, product, and services, they were struggling to. We're now working with select businesses to co-innovate, research, analyze, recommend, implement, and, finally, train their organizations on AI. Interested? Contact us to start a conversation.

Don Estridge literally gifted the entire personal computing market to IBM. When we first saw him in this series, he was competing with Lore Harp to build the first personal computer. We’ve seen that story from her perspective—now it's time for Estridge's. You might think that the man who ushered IBM into the PC age would have been a central figure within the company, but in reality, he worked in the relative backwater of its Boca Raton, Florida office. This is the story of how Estridge successfully navigated complicated corporate politics to build the iconic IBM PC—and his shocking betrayal. It's the latest installment of The Crazy Ones, Gareth Edwards's monthly column about the forgotten men and women who built the future of technology. Subscribe to Every so that you don't miss out.—Kate Lee

In a burnished-oak corridor outside the committee room at IBM’s headquarters in August 1980, two engineers pace nervously. Eventually, a door opens. Their boss, Bill Lowe, emerges from the board room next door. Before they can say anything, he smiles and nods. They laugh. They can’t quite believe it. It’s official. IBM is going to try and build a home computer.

Bill Lowe kicked off this ambitious project, but he wouldn’t be the person who would finish it. That role would fall to his successor, a humble, cowboy boot-wearing mid-level executive, out of favor and kicking his heels in the IBM corporate backwater of Boca Raton, Florida. He would take Lowe’s project forward, one nobody else in the company wanted. Just 12 months later, on August 15, 1981, a computer would launch that would change the world: the IBM PC.

This is the story of Don Estridge, the man who brought the IBM PC to market and changed business and home computing forever. In just five years he created an IBM division that almost nobody else in the company wanted to exist. By 1983, it had seized 70 percent of the microcomputer market and was valued at over $4 billion ($12 billion today). Under Estridge, IBM’s PC division sold over 1 million machines a year, making it the third largest computer manufacturer in the world on its own. This story is based on contemporary accounts in publications such as InfoWorld, PC magazine, Time, and the New York Times, as well as books such as Blue Magic by James Chposky and Ted Leonsis; Big Blues by Paul Carroll; and Fire in the Valley by Michael Swaine and Paul Frieberger.

‘Where’s my Apple?’

In 1980, no one senior at IBM wanted to build a microcomputer, as home computers were often called, except its CEO Frank Cary. But one man’s will was far from enough to get things done at IBM, even if he was the CEO.

In the late seventies, IBM was vast. Known as “Big Blue” to its friends and enemies, the company had almost 350,000 employees, ran so many branches, and operated in so many markets that one commentator at the time described IBM as a country, not a company. It made mainframe and minicomputers that filled rooms—sometimes, whole buildings—and cost vast sums of money. It made business electronics, dominated the global market for typewriters, and made millions selling a wide variety of office supplies. A former employee would later describe it even more accurately: IBM didn’t stand for “International Business Machines.” It stood for “International Business Mafia.”

IBM’s huge divisions, spread across the U.S. and the rest of the world, operated like a series of global mafia families. They cooperated when under threat from the outside, and occasionally fought. The heads of those corporate families would regularly come together at the company headquarters in Armonk, New York to form the Management Committee. There, under the watchful eye of IBM’s CEO, they made decisions that would shape IBM’s business empire globally.

Cary started at IBM in 1948. He’d been its CEO since 1972. He had helped it dominate the world of mainframe computing, selling machines that could cost tens—or even hundreds—of thousands of dollars. But he also didn’t believe that the company should rest on its laurels. The Apple II personal computer had been selling in enormous numbers since 1977. At these meetings, he had one question for IBM’s divisional capos.

“Where’s my Apple?”

His divisional heads always had the same answer. Microcomputers—home computing—were a fad. They were low-cost and low-profit. Let others scrabble around in the metaphorical dirt of home computing. The real money was in the markets that IBM’s divisions already dominated—selling vast mainframes and minicomputer systems to large businesses. Cary was even told to buy Atari, which by then had established itself as America’s home video game system of choice. That’s all home computers were good for: gaming.

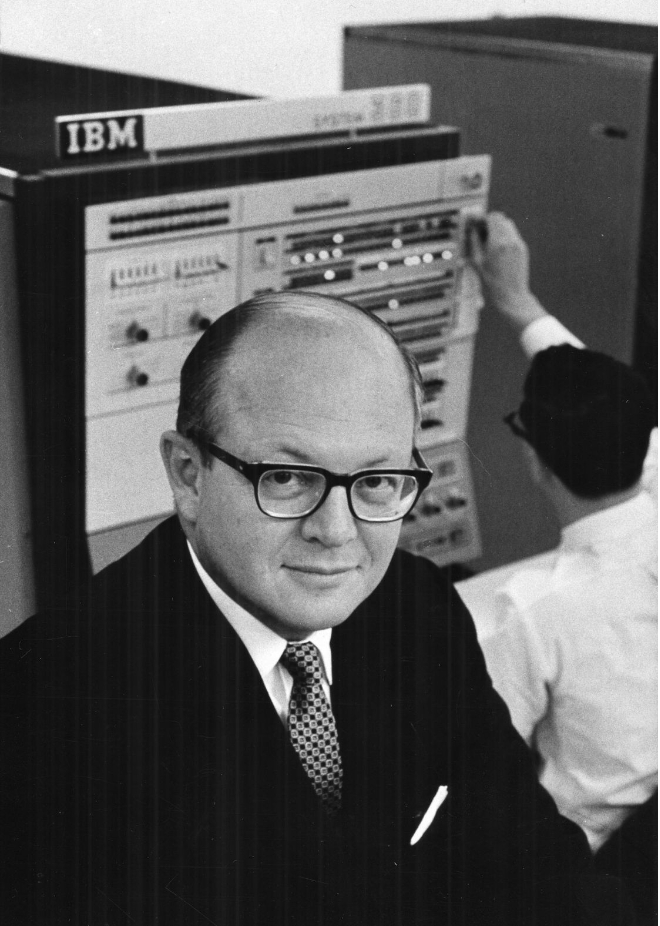

Frank Cary in 1972. Credit: IBM.

But Cary didn’t back down. In July 1980, he finally forced a concession out of John Rogers, the head of IBM’s General Products Division (GPD). Rogers agreed to set up a project to create a prototype IBM microcomputer—as long as it didn’t come out of his budget.

The answer lay in Boca Raton, Florida. There, lurking near-forgotten in his vast empire of typewriters, photocopiers and other low-level business electronics, was the Entry Level Systems (ELS) Facility, headed up by one of Rogers’s lieutenants, Bill Lowe. It was a leaky, rundown concrete facility that existed primarily to research and prototype basic electronics. Lowe, who was one of the few microcomputer supporters at IBM, was summoned before the Management Committee in July 1980. He was assigned to “Project Chess” and told to create a prototype of a microcomputer. Lowe was given one month to do so, after suggesting to the Committee that one could be assembled from off-the-shelf parts. And he would report directly to Cary. After all, Cary was footing the bill, not Rogers.

To pull off this minor miracle of engineering, Lowe assembled a core team known as the dirty dozen (there were 13 of them in total). They were a mix of engineers and planners taken from a number of different divisions. Mostly, they were individuals who struggled to fit in with the risk-averse, rules-heavy way of working within IBM. Bill Sydnes, for example, was a talented engineer who had taken the initiative on a failing project and spun off parts of it into a success. His reward for doing so was a reprimand for going outside of IBM’s standard operating practices. Other misfits, like systems engineer Lew Eggebrecht and software engineer Jack Sam, joined for similar reasons—a chance to work on a project with few limitations.

The project seemed doomed to fail. Mainframe computers were very different from microcomputers, and nobody at IBM had any real experience with the latter. Even if suitable off-the-shelf parts could be found, there was no guarantee those parts would work well together. They’d also need to program their prototype to do something that proved it would work. The risk that problems would occur was high, and they’d been given little margin to fix those that did. But it would be a fun way to spend a month. And as most of them were out of favor within IBM, they had little to lose.

To their own surprise, after a frantic month of development, this team pulled it off. They created a machine that worked. The computer didn’t do much, but it was enough to show the Management Committee.

"The system would do two things. It would draw an absolutely beautiful picture of a nude lady, and it would show a picture of a rocket ship blasting off the screen,” Bill Sydnes confessed later. “We decided to show the Management Committee the rocket ship."

This demo, held in August 1980, convinced Cary and the Committee that the work should continue—for now. They told ELS to turn its prototype into a product—and to do everything else needed to take it to market.

Lowe was under no illusions about the difficulty of this task. He was convinced that the project was valuable, but Cary still seemed to be the only senior figure within IBM who agreed. The various division heads wanted nothing to do with the project. But as long as the cost (and any eventual blame) sat squarely on the ELS facility in Boca Raton, they didn’t feel a need to kill it. What the Committee did, instead, was impose a deadline for launch: August 1981. It was another impossibly tight deadline, just one year away.

Lowe headed back from the headquarters in Armonk, New York to Boca Raton with Sydnes and Eggebrecht. There, the dirty dozen began the necessary work to turn their prototype into a real machine. But Lowe, who was seen as a rising star within the company, was already being considered for a new, bigger role elsewhere in IBM. Soon his promotion to that position was confirmed.

Lowe believed in the project but didn’t believe he was the right person to do it. Taking it forward would require a unique set of leadership skills. It had to be led by someone who thrived on breaking the rules and who could use the ELS’s newfound position outside the regular financial and management structure to its maximum. Luckily, Lowe knew just the man within IBM for the job—Philip “Don” Estridge.

A company man

Don Estridge turned 43 in August 1980. He had been an IBM man his entire professional life. He loved being able to tell people he worked there. He would tell people that his blood ran big, and it ran blue.

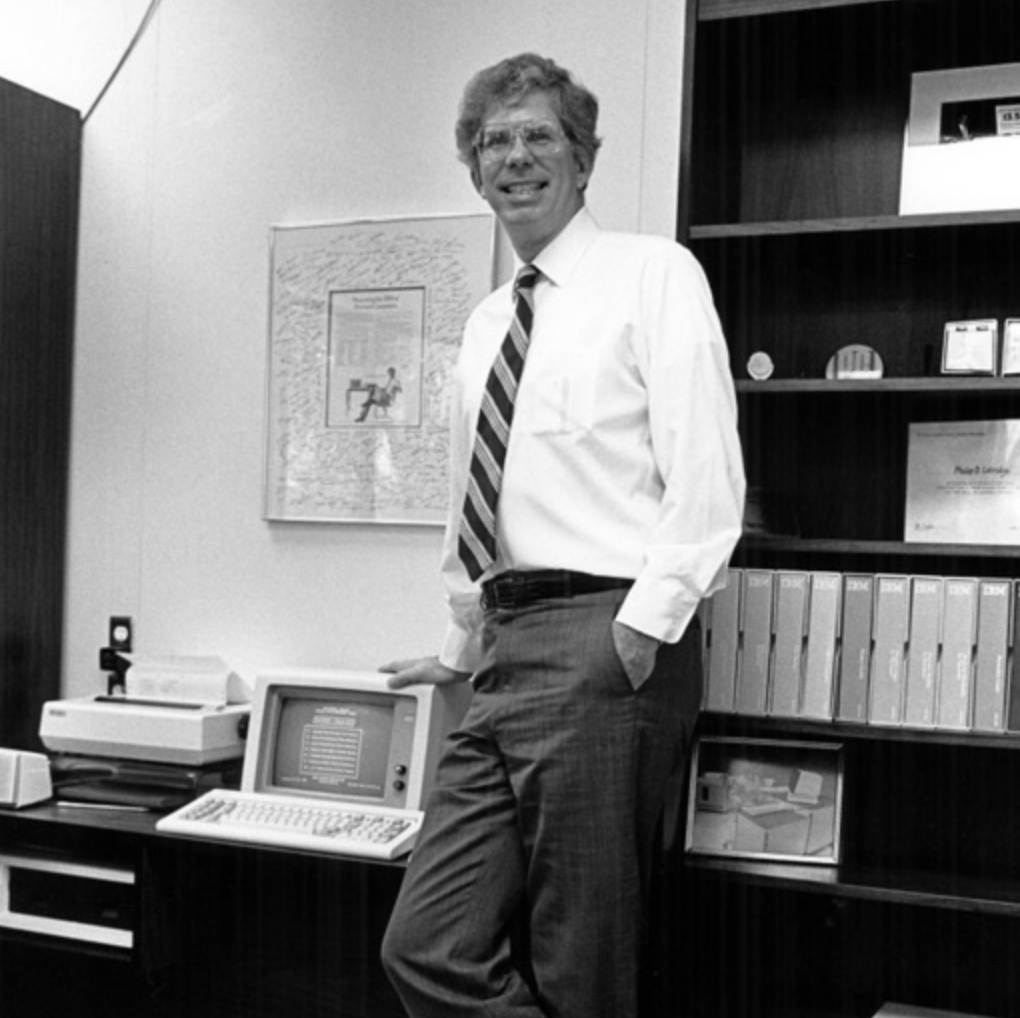

Don Estridge in 1983. Source: IBM.Yet in many ways, Estridge ran as counter to the grain at IBM as the rest of the dirty dozen did. Tall with a mop of well-kept hair, Estridge wore the crisp suit, shirt, and tie that was the standard uniform for an IBM executive. But he coupled that look with a pair of expensive cowboy boots that often drew frowns from more senior executives. He was a humble man who had no time for flattery and a strong distaste for corporate politics. In IBM, this made him unusual. His fellow senior executives would frequently complain that he failed to return their phone calls, and rarely agreed to join golf sessions or long lunches. And his junior staff noted that he made a deliberate effort never to sit at the head of a table. Estridge believed in collegiality, not seniority.

Estridge was hugely charismatic, although his personal magnetism was drawn from a different source than that of Steve Jobs at Apple or Adam Osborne at Osborne Computing. They were men who sold their own visions. They could create “a reality distortion field” around themselves (a term coined by Apple’s Bud Tribble about Jobs). They could convince you of the value of their ideas and inspire you to give everything in their service.

Estridge was the polar opposite. He listened and supported. His role was to set objectives and provide people with the resources or political cover they needed. This approach inspired a different kind of loyalty from those who worked for him, but it was just as fierce. And it delivered results.

Lowe had seen how effective Estridge had been on the IBM Series/1 minicomputer project. The Series/1 was intended to be flexible enough to serve a variety of big business computing needs. It would be a workhorse that businesses would buy in large numbers, making IBM healthy profits on its five-figure price tag. But its development was plagued with problems and project overruns, and the end result was criticized for being underpowered. As a result, the Series/1 project was regarded as a failure within IBM.

However, one small part of it was successful. IBM’s sales department had secured a large contract to convert all of State Farm Insurance’s operations to run on Series/1 machines. That part of the project had been led by Don Estridge, who had managed the production of these specific machines, complete with required software. They had been delivered to State Farm on budget and on time.

When the Series/1 project ended, Estridge found himself tied to its wider failure—and out of favor. But IBM didn’t fire people who might still be useful. It simply sidelined them. They would be sent somewhere quiet and remote in case the company decided it needed them again. So Estridge was thanked for his work and sent into the Florida wilderness, to kick his heels in the corporate backwater of Boca Raton.

Estridge was a self-confessed computer nut. In his early IBM years, he had worked on radar systems for the military and software for NASA’s Apollo programme. Estridge was amazed by the Altair 8080, the world’s first home computer. He never believed that he might one day have a computer at home. And when Apple released the Apple II in 1977, Estridge bought one for himself. During the day, he would help IBM build mainframes and minicomputers. In the evenings, he would tinker with a computer of his own.

When Estridge heard about Project Chess, he wanted in. Lowe was happy to recommend him to the Management Committee as his replacement. In the fall of 1980, Estridge took over. He brought his Apple II with him, setting it up in his office at Boca Raton. If he felt that visitors weren’t seeing the value of microcomputers, they would be subject to an extended personal demonstration of what the Apple II could do until they conceded his point.

Going it alone

Nobody at the ELS would later remember how the machine they were building acquired the nickname “Acorn,” just that it was a sideways nod to “Apple.” Whatever the name, no one outside of the department seemed to care.

Lowe had warned Estridge to expect this. In early September, ELS approached the management of IBM’s new assembly plant in Boulder, Colorado. The new plant was significantly under capacity, and Lowe had offered them the chance to build the Acorn. He had received a polite but firm refusal. Boulder’s senior management would rather let their plant sit idle than associate themselves with Project Chess.

However, although IBM senior management clearly didn’t want anything to do with the Acorn, plenty of junior staff did. This would become a trend—senior management would first tell Lowe, then Estridge, to go away. Junior staff would be more interested. Those with useful skills would be lured down south to join Estridge’s ever-growing group of misfits in Entry Level Systems.

“We got some excellent people out of Boulder,” Bill Sydnes confessed later.

Estridge and his senior team quickly realized that the only way they could get their home computer to market was if they did everything themselves. Whenever Estridge was told that yet another IBM department or division refused to cooperate, he would fly from Florida to IBM’s corporate headquarters in Armonk, New York. There, he’d petition Frank Cary for more money or people before returning home once again. It was difficult to secure additional resources at IBM—even if upper management believed in what you were doing. Yet, to the astonishment of his senior staff, Don Estridge was almost always successful. His charisma and quiet persuasiveness got him the concessions he needed. At their height, these trips were happening two or three times a week.

Finding a market

Estridge was lucky enough to inherit two things from Lowe: a viable design for a mass-market microcomputer and a core team of competent and enthusiastic engineers. It was Estridge, however, who realized that they should enter the small-to-medium business market, not home computing.

The design that Lowe’s team had developed was perfect for this. Nothing about their design was pioneering, but it provided enough power, at a low enough price, to run basic small business software, such as word processors and spreadsheets. Historically, IBM had ignored this market because these companies didn’t have the five- or six-figure budgets needed for mainframes or minicomputers. However, they did have enough money to buy a single machine for $5,000 dollars or less. These same business users associated IBM with good things. As the saying went, no one ever got fired for buying an IBM.

However, to turn a profit, they would need to sell in volume, which meant making a lot of machines. Estridge’s options for manufacturing support within IBM were limited, so he took a trip to California to meet Lore Harp, CEO of Vector Graphic. Under Harp’s leadership, Vector had carved out a niche for itself making computers for the small business market. The company also had a reputation for quality that matched IBM’s. Estridge toyed with a partnership. He asked Harp to sign an NDA, and then revealed that IBM was considering a small move into this market itself. The discussion was friendly, but Harp was wary. Estridge left with five Vector microcomputers and a vague agreement that they should talk again.

While the offer to partner had been genuine, it would never take place. Instead, Harp would find herself rushing to save her business as Estridge filled out his senior team with individuals interested in going up to the challenge of the ELS alone.

A well-led team

Word spread quickly that Cary had given Estridge and the ELS freedom to operate outside of IBM’s byzantine structures and processes. As operations expanded rapidly in Boca Raton, it became clear that Estridge wasn’t afraid to use this authority.

Dan Wilkie, who came on board to lead production, experienced first hand what a difference this freedom made. With Estridge helping to cut through red tape around budgets, staffing, and processes, Wilkie created an assembly facility from scratch in about four months. The previous unofficial record for doing so at IBM stood at three years. He became one of Estridge’s most loyal and effective lieutenants.

“With the PC project, I saw the whole pie for the first time,” Wilkie said later. “We saw the costs, we solved the problems ourselves. We lived with the good and the bad. It’s no exaggeration to say that I made more decisions in the first 30 days with that group than I made during my first 14 years with IBM.”

Also critical was the recruitment of H.L. Sparks, known to his friends and colleagues as “Sparky.” A born salesman and a rising star within IBM, Sparks first encountered Estridge after the Series/1 project ended. Sparks could see that Estridge was a talented manager. When the Series/1 project had shown signs of failure, others had shifted the consequences elsewhere. Sparks was impressed that Estridge had done the opposite, shielding his team from blame, even though it meant accepting corporate exile to Boca Raton for himself. Then, in December 1980, Sparks received a call from Estridge, who offered him a job.

“A job doing what?” Sparks replied.

“Don’t ask. It’s a really great deal. Trust me and just say yes.”

Sparks didn’t hesitate, abandoning 18 years of climbing the ladder the IBM way to join the project. Estridge put him in charge of marketing and distribution. There was no point in having a machine if users didn’t know about it or have a way to buy it.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.50.43_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

"red rosettes cast pink shadows in the pale morning light" that's poetry and a perfect description of loyalty and team leadership !

This was an incredible piece of writing. Very rare to have such an ostensibly dry piece of history fleshed out so colourfully and in such a human-centric way. Thoroughly enjoyed, thank you Gareth.

The PC was supposed to be announced in July, 1981. The announcement was delayed a month because the System 24 Datamaster was announced that month.

@davidschwaderer.001 This is Kate Lee, Every's EIC. Thank you for this comment. We may include the comment in our upcoming Sunday digest. Would you let us know your job function?

@kate_1767 In June 1981, I was an *outside* advisor to the IBM PC Strategic Planning Group. The entire PC organization had about 100 people when I stared working with them. Two years later, there were 10,000 folks in the IBM PC group.

I was later selected to be one of two Chief Programmers for OS/2 but had to withdraw literally at the last second because of my wife's cancer scare.

Now, I am CEO of ShapeShift® Ciphers - creator of the world's first Deterministic Chaos based data encryption technology that stalemates classical, Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Quantum Computer attacks using mathematics-free Quantum Qubit Superposition emulation.

www,ShapeShiftCiphers.com

Try it, you'll like it.............there's an article there for you...........guaranteed.

[email protected]

Surely “Bill Sydnes”, not “Bill Snydes”?

Fascinating to read what happened to the PCjr.

Some may be interested to note that the PC AT shipped with a 286 in 1984. The PS/2, launching with a 286 six months *after* the Compaq Deskpro, must have caused quite a lot of stunned silence, especially to anyone familiar with the advantages of the 386’s memory addressing (and the flaws in the 286’s in relation to programmability).

@Stuart Brady This is Kate Lee, Every's EIC. Thank you for the spelling correction and this comment. We may include the comment in our upcoming Sunday digest. Would you let us know your job function?