.50.43_AM.png)

The history of the personal computer wasn't just about technology—it was about vision, trust, and the courage to stand up to a monopoly. In his latest piece for The Crazy Ones, Gareth Edwards tells the story of how Compaq challenged IBM's dominance in the 1980s. When IBM tried to reclaim control of the PC market with proprietary technology, Compaq CEO Rod Canion decided to create an open standard and share it with competitors—effectively giving away "the company jewels" to preserve innovation. Gareth explains how Canion's leadership style created both a beloved workplace culture and the backbone needed to face down the industry giant. Just think—if IBM had won, we might be living in a very different technological landscape.—Kate Lee

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

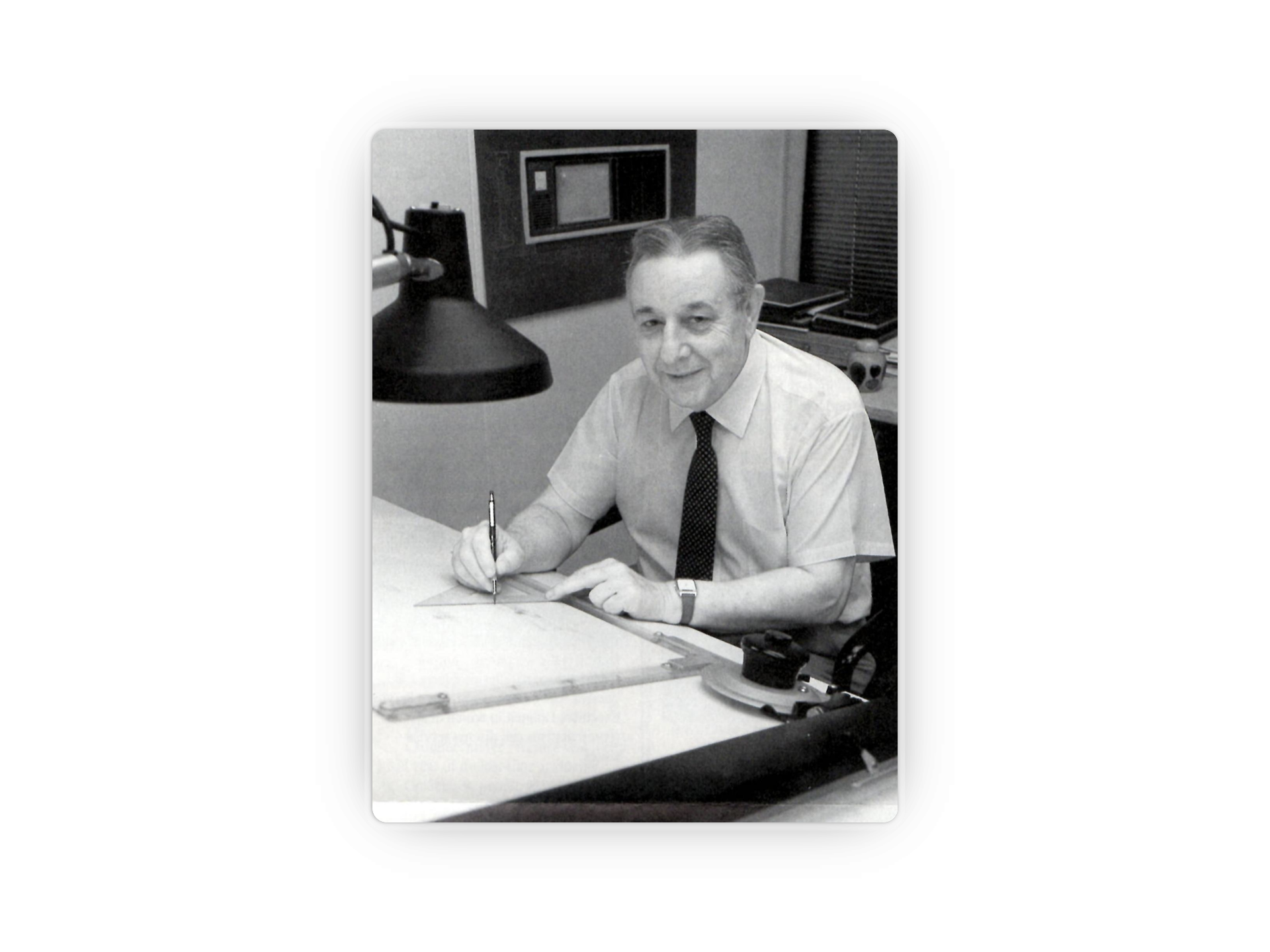

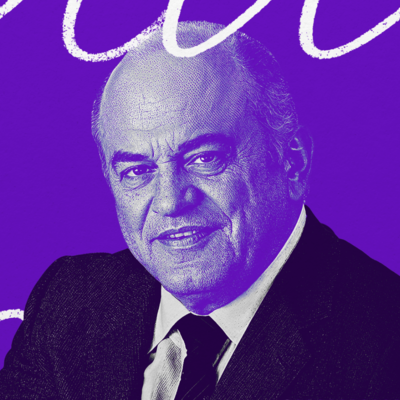

As CEO of Compaq, the most successful of the companies making IBM personal computing “clones,” there weren’t many people Rod Canion would always take a call from. Bill Lowe, the head of IBM’s personal computer business, was one of them.

It was September 9, 1988. The two men chatted amiably for a few minutes before Lowe made Canion an offer. IBM was prepared to give Compaq unparalleled access to its new, proprietary next-generation PC technology. All Canion had to do in return was cancel the press conference Lowe knew he had planned for the following week.

The call caught Canion off guard. The conference was to announce that Compaq and eight other major PC companies had agreed to keep the current PC technology as an open design standard, in outright opposition to IBM. Yet here was Lowe with a counter-offer: Abandon the others. Split control of the multi-billion-dollar PC market between Compaq and IBM. The two companies could rule it together.

The financial upside for Compaq was huge. It would be insane to turn it down. Besides, everybody knew you couldn’t win against IBM. There was silence for a moment. Then, calmly and politely, Canion gave Lowe Compaq’s answer.

Lowe listened and sighed. “I think you’re making a big mistake,” he said, and ended the call.

Four days later, Canion stepped onto a New York stage and did the unthinkable. He declared open war on IBM.

This is the story of Rod Canion and Compaq. It is the story of the battle for the soul of the personal computer, and the fight to prevent IBM from taking back full control of the technology behind it. It is based on contemporary accounts in the New York Times, Time, PC Magazine, Byte, and Infoworld as well as books such as Blue Magic by James Chposky and Ted Leonsis, The Fate of IBM by Robert Heller, Big Blues by Paul Carroll, and Open by Rod Canion. It draws on interviews with key figures such as Ben Rosen and L.J. Sevin conducted for the film Silicon Cowboys and for the Computer History Museum. It is also based on interviews with Rod Canion conducted by the author himself.

Starting the company

Rod Canion, Jim Harris, and Bill Murto were company men. By 1981, all three had worked at Texas Instruments (TI), which made electronic products like calculators and computers, for years. In their forties with families, they were more likely to be seen in crisp suits and ties than the loose shirts and slacks already the stereotype in Silicon Valley.

Yet in September 1981 the three friends sat around the dining table in Murto’s Houston home and questioned their future at TI.

“We got a bad boss,” Canion said later. “He just wasn't fun to work for. He wasn't a bad person! Just… not a good boss."

It didn’t help that all three of them made regular trips to TI’s contractors or clients in Silicon Valley. They’d see the Porsches and Ferraris in parking lots. Maybe that could be them. They decided to form a company of their own.

They briefly considered setting up a restaurant—Mexican food was a shared passion—but swiftly discarded the idea. They were all passionate about, and had worked with, computers. So they decided to do something for the IBM PC.

"It was obvious to anybody paying attention, there was gonna be an explosion in the PC market." Canion said.

The PC was designed to be expanded. Not just by IBM, but by anyone. Any company could create plugin computer boards, peripherals like disc drives, or accessories that would work with the machine. This “open architecture” approach was a bold thing for a company to do. That Big Blue (IBM) had chosen this path seemed miraculous. It liked making big, expensive computers that nobody other than IBM was allowed to touch. But Don Estridge, the creator of the PC, believed that the best way for IBM to succeed in the home and small business market was to make a machine that used common industry parts and acted as a standard platform. It worked. By September 1981, the PC was the hottest item in computing, on track to sell more than 250,000 units by the end of the year.

At TI, Canion had led a hard drive project for a different type of computer at TI. It was how he had met Harris and Murto, so doing the same thing for PCs felt like it would be familiar ground. Leaving TI would be tough, though. All three men had little savings. They needed venture capital, but in 1981 that industry barely existed and what investment was available was mostly focused on Silicon Valley. Canion and the others didn’t know how to access venture capital, or who could provide it.

Luckily, Canion soon encountered someone who could help: Portia Isaacson.

Isaacson was ex-U.S. Army. After she was discharged in 1962 she worked as a programmer at Bell Helicopter, Lockheed, and Xerox PARC. Then, in 1974, a company called Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems (MITS) released the very first home (or “micro”) computer—the Altair 8800. Isaacson fell in love with it. By 1981, she had founded a consulting firm in Dallas focused on predicting trends in computing.

Canion met Isaacson in October 1981 when she came to Houston to consult for TI. Sensing that she might be able to help, he gave her a lift back to the airport after her work in Houston was complete.

Humble and soft-spoken, with a gentle Texas lilt, Canion’s relaxed attitude concealed a quick mind that contrasted with the brash and flamboyant personalities that dominated senior management at most technology firms at the time. He didn’t over-promise on projects; he delivered. He didn’t boast about his successes; he shared credit. Isaacson liked him. Not only did she give him the advice he needed, she went one further. She connected him with her friend, L.J. Sevin.

Sevin had cofounded chipmaker Mostek. In 1979 the firm sold for $345 million—about $1.5 billion today. Less than a month before Canion’s conversation with Isaacson, Sevin teamed up with New York technology analyst Ben Rosen to launch a venture capital firm called Sevin Rosen. Sevin had worked at TI before founding Mostek, so Isaacson suspected the two men would get on. There was also something else that made Sevin, as a newly minted venture capitalist, very rare. He lived in Texas.

“I think he liked us because he didn’t have to fly anywhere,” Canion joked later.

Sevin liked Canion’s hard drive idea, and so did Rosen. They agreed to pitch it to other venture capital firms to see if they could secure a second backer, something they required before they’d invest. Sevin also gave Canion a warning.

“Don't take anything with you but what's in your mind,” he said.

"We knew that they would sue us if we stole anything,” Canion said later. "L.J. [Sevin] reinforced that though. There's no doubt."

From the beginning, Compaq’s founders understood the danger of being accused of intellectual property (IP) theft.

On December 4, 1981, Canion and Harris resigned from TI. Murto followed a few months later; his wife had just had a baby, and the couple needed the post-natal care his insurance was providing.

The portable

Canion and Harris were together at Harris’s house a few days afterward when the phone rang. It was Ben Rosen. Rosen told them that he’d been unable to find a second investor for their hard drive plan. But if they could find a new idea, then Sevin Rosen would be happy to look at that, too.

Canion and Harris could have withdrawn their resignations from TI. Instead, they decided to double down. They registered their new firm (with the holding name of “Gateway Technology”) and paid $1,000 each into its bank account.

“Our excitement about starting a company was tempered by the knowledge that we had set aside only six months of living expenses for our families,” Canion wrote later.

They had six months to come up with an idea that Sevin Rosen would back.

A lot could change in six months. Indeed, just six months earlier, the writer and flamboyant technologist Adam Osborne had stunned the world of computing by launching the first truly portable computer, the Osborne 1. Canion found himself musing on that at breakfast one January morning in 1982. Then it came to him.

“I was struck by an idea that was so simple and obvious it sent a chill down my spine,” Canion wrote. “What if we could make a portable computer run the software written for the IBM PC?”

It seemed like such an obvious idea that they couldn’t believe that someone else wasn’t trying it already. As they worked through the details, however, they realized there was a difference between obvious and easy.

Computers are more than just software and hardware. Software rarely interacts directly with the hardware on which it runs. It runs within an operating system (OS), such as Windows or Linux today. That OS talks to the hardware using a shared language of instructions and routines, known as the Basic Input/Output System (BIOS), burned into a chip on the hardware itself.

One reason Don Estridge was confident about his open approach to the PC’s design was that although anyone could put together similar hardware, the BIOS IBM’s PC used was proprietary code—the intellectual property of IBM. A company wanting to “clone” (as it became known) the PC would need to write its own BIOS, but to run the same OS and software as the IBM PC, it would need to respond to every instruction exactly the way IBM’s own BIOS did. Otherwise, the OS and software would crash.

Creating the hardware for a portable clone of the IBM PC was easy. Replicating the BIOS in a way that wouldn’t infringe on IBM’s copyright was hard. The men believed they knew how to do it, though.

Creating a clone

“You crazy bastards,” Sevin said.

It had taken a few weeks to pull together a technical specification for a portable PC. After that, Harris and Canion sat down in a Houston House of Pies with a retired industrial designer named Ted Papajohn. On the back of a placemat, Papajohn created a rough sketch of a prototype according to their instructions: It needed to look like an Osborne 1, but “less army surplus.”

That specification, a business plan, and a cleaned-up photocopy of Papajohn’s visualization was in the presentation they had just handed to L.J. Sevin and Ben Rosen.

Both Sevin and Rosen were doubtful. Creating a portable PC clone seemed an insurmountable challenge.

“We liked the guys,” Sevin admitted later. “I did a little background checking on Rod [Canion] and it all came back positive.”

A few days later, Rosen called Canion and Harris. He confirmed that Sevin Rosen would provide investment capital, conditional (once again) on another investment firm joining them. This time, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers agreed to do so. With a total $3 million investment, Compaq—as the company would soon be renamed—was a go. Rod Canion became CEO while Ben Rosen agreed to serve as board chair.

Design work on the “Compaq Portable” began in March 1982. The Compaq founders had persuaded a number of TI employees to jump ship with them, though they’d had to be intentionally vague on what the work would involve to avoid legal issues with TI. This group included hardware engineers Steve Ullrich and Ken Roberts, who would prove critical to working out how to clone the IBM PC, and Steve Flannigan, a software engineer. As soon as Ullrich and Roberts joined, Canion was contacted by a third TI engineer, Gary Stimac. He was so desperate to join the others at Compaq that he’d already handed in his notice at TI. So they hired him as well.

At their new Houston offices and (according to Stimac) after plying their new engineers with enough pizza to soften the shock, Canion, Harris, and Murto told their new employees what they needed to do: Create a portable IBM PC clone. And not just one that could run some IBM PC software—other companies were already boasting about that—but a clone that could run all of it. One hundred percent compatibility. When they questioned this, Canion insisted that anything else wouldn’t stand out from the crowd. One hundred percent compatibility. No less.

It was a huge challenge, not least because, with PCs selling so well, it was hard to find a retailer that had them in stock. Stimac found one in Dallas, and flew there to buy a machine. He returned triumphant. Not only had he bought a PC they could dissect, but he’d also read its technical manual on the plane. That manual contained a full breakdown of how the PC’s BIOS worked. He told Canion and Flannigan he was confident that he could copy it. Canion and Flannigan groaned.

“Stimac had unknowingly contaminated himself by looking at the code printed in the IBM manual,” Canion wrote.

IBM printed the technical breakdown of its BIOS because it made it easier for software or peripheral makers to create products for the PC. But that didn’t stop the BIOS from being proprietary technology in the eyes of the law. If Stimac now worked directly on a BIOS that replicated its functionality, IBM’s lawyers could claim copyright infringement.

Many clone manufacturers would fall prey to this honey trap over the years. Big Blue would dispatch hordes of lawyers to descend on them. The inevitable result was bankruptcy or huge licence fees that reduced their ability to compete.

So Stimac, Flannigan, and Compaq’s legal counsel sat down together and worked out a way to create a functional specification for a cloned BIOS—one that would allow them to leverage Stimac’s knowledge without contaminating anyone else and leaving them open to legal action from IBM.

Stimac would read the documentation, and from that he would describe how the BIOS functioned to a lawyer. The lawyer would then write a functional specification based on what he said, stripping out any information they felt was proprietary to IBM at this stage. The resulting specification was given to Flannigan and the other engineers. They would use it to create a “best guess” clone of the BIOS and fix any mismatches in behavior through trial and error.

This became known as the “clean room” method. It was resource-intensive and time-consuming. But it worked.

“Nobody in the entire office could ever buy a copy of a technical manual after that without me removing the [BIOS] pages and destroying them,” Stimac said later.

Unable to work directly on the BIOS, Stimac was instead tasked to source an operating system that was fully compatible with IBM PC software.

This should have been relatively easy. The computer used an operating system called PC DOS (Disk Operating System), made by Microsoft. In negotiations with Microsoft founder Bill Gates, IBM had agreed that in return for a cheap per-unit license, Microsoft could sell a version as “Microsoft DOS” to other companies as well.

It was a deal that IBM regretted almost instantly once its PC became popular because companies like Hewlett-Packard—and now Compaq—could buy a version of DOS to run on their “PC clones.” And it was this ability to sell the non-IBM PC version of its software without IBM getting a cut that made Microsoft the financial success it is now. In theory, software made for the PC should now work on these clones. But as Stimac started testing Microsoft DOS with Compaq’s new computer, he spotted something odd. Microsoft DOS was meant to be exactly the same as the PC DOS, but it wasn’t. It would occasionally cause PC software to crash or not run at all on a clone.

Other clone companies likely attributed these crashes to flaws in their hardware or cloned BIOS. Stimac was convinced it was a problem with Microsoft DOS itself. So, in March 1982, Rod Canion traveled to San Francisco to meet with Bill Gates. The two men chatted amicably for a while. Canion looked Gates squarely in the eye and revealed what Stimac had told him:

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

I was living and working in both Seattle and Mountain View during the early years this story was playing out. Learned DOS on my CompQ, CPM on my Osborne, and for a short while participated in introducing DEC’s Rainbow PC to the retail market. This essay brought back some amazing memories. Thanks.