I have vivid memories of my family's first computer: a blocky Commodore 64 parked in a corner of our basement, its cursor blinking on a royal blue screen. It was just one of the more than 12 million units sold, an astonishing business success pioneered by a Holocaust survivor and Polish immigrant named Jack Tramiel. In his latest piece for The Crazy Ones, Gareth Edwards recounts Tramiel’s journey from Auschwitz to founding Commodore, and later reviving Atari. His ruthless approach to vertical integration and relentless cost-cutting made computers accessible to millions of families who could never have afforded them otherwise—launching a generation of tech careers and helping shape our digital present. Plus: Listen to an audio version of this piece on Spotify or Apple Podcasts.—Kate Lee

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

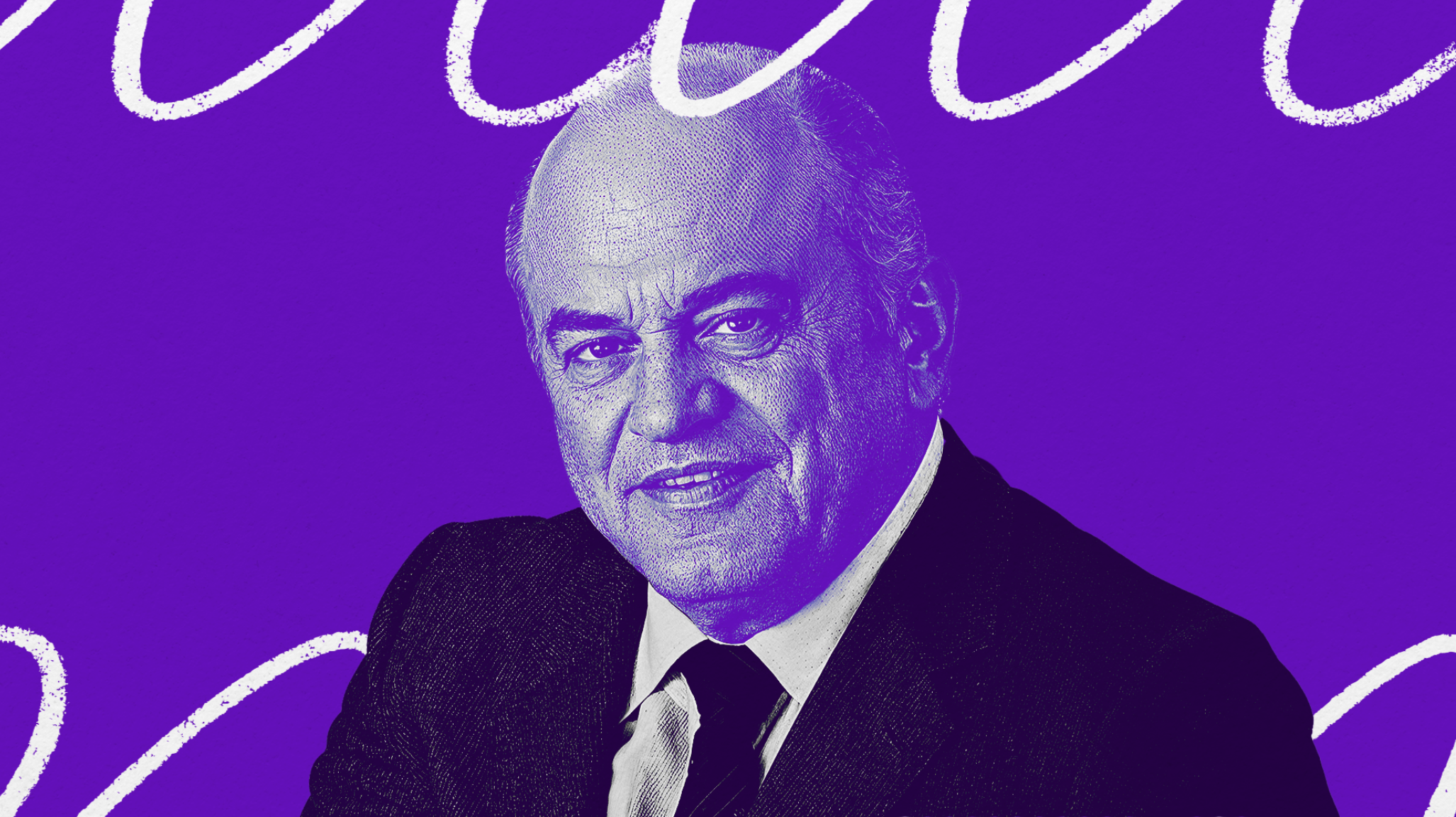

In 1980, Commodore opened its first computer factory in Germany. In just three years, the company had become the third-largest computer manufacturer in the world. With annual revenue of $680 million (more than $2.2 billion today), its success was largely due to its Polish-American founder, Jack Tramiel. As he ascended to the front of the 2,000-employee crowd at the new factory, he was advised to avoid mentioning his past. Specifically, to omit that he’d been a prisoner in Nazi slave camps and at Auschwitz during the war. Tramiel listened to the advice and took to the stage.

“I told them I was Jewish and that I was a survivor of the concentration camps. And then I said that I wanted anyone who was in the SS in my office in the next two days.”

Nobody—nobody—told Jack Tramiel what he could or couldn’t do.

Over the next few days, six men resigned saying that they would never work for a Jew. Over 15 others presented themselves to Tramiel and confessed that they had served in the SS. Tramiel thanked each man for his honesty, offered his forgiveness, and then told them to get back to work. He was determined to make Commodore a business of the future, not the past. He just wanted them to know who he was. And that they worked for him now.

This is the story of Jack Tramiel, one of the most explosive and ruthless founders the computer industry has ever seen. It is the story of four machines—the PET, VIC-20, Commodore 64, and Atari ST—and of the man who ruled home computing for over 20 years.

This account is based on contemporary accounts in Time, Fortune, and the New York Times, as well as books such as Back into the Storm by Bil Herd, Retro Tech by Peter Leigh, and The Home Computer Wars by Michael Tomczyk. I am particularly indebted to Commodore: A Company on the Edge by Brian Bagnall, and to both the Computer History Museum and the Commodore archive for their considerable archive of material. It is also based on the words of former Commodore executive and computer designer Leonard Tramiel, creator of the PET computer Chuck Peddle, and former editor of Commodore’s print publications Neil Harris. Also, on the words and testimony of Jack Tramiel himself.

Coming to America

When Idek Trzmiel was an adolescent, he worked as a tailor’s apprentice in Łódź, Poland. In 1939, at the start of World War Two, Trzmiel, who was Jewish, was sent to the Łódź Ghetto with his family. He would spend the next five years there fighting to survive and to avoid being deported to Nazi Germany’s extermination camps. In 1944, the Łódź Ghetto was finally liquidated and its remaining occupants were marked for death. Alongside his father, Trzmiel was sent to Auschwitz. During the process of liquidation, they lost touch with Trzmiel’s mother.

By that time, Trzmiel was 16. He was saved by his ability to work. At Auschwitz, he and his father were among the small number of Łódź deportees selected by the camp authorities for survival. For almost a month, they were used as slave labor within Auschwitz itself, witnessing some of the worst horrors of the Nazi regime.

Trzmiel escaped death at Auschwitz by the narrowest of margins. In August 1944, Germany’s desperate need for slave labor at home meant that approximately 10,000 people were relocated from Auschwitz to a new work camp in Hanover. The Trzmiels were among them. They were saved from death, but this salvation would prove only temporary for many. As slaves, they were treated brutally. Once they were no longer able to work, they were killed.

In early 1945, this fate befell Idek’s father. Because he was no longer able to work, he was murdered with an injection of gasoline. By April 1945, only 250 of the original slave laborers sent to the camp from Auschwitz were still alive. This number included Idek. They were emaciated and unable to work. The Nazis ordered them to start digging their own graves. Right at that time, American forces finally reached the camp and liberated it.

Idek spent three months recovering in an Allied hospital in 1945. Amid the chaos of liberation and immediate post-war Germany, Idek, like many others, struggled to come to terms with what they had just survived.

“I came out like a wild tiger,” he remembered later. “I wanted to get back everything I had lost.”

Like many survivors, Idek struggled to understand his experience. Over the next two years, he took odd jobs in Germany wherever he could find them. He also became fixated on revenge. When a German police officer disparaged his Jewish background, he beat him, which led to Idek’s arrest and trial for assault. A sympathetic American lieutenant helped him escape jail by telling Idek the exact statutes he needed to cite to be sentenced as a Polish combatant, rather than as a civilian survivor. As a result, he was sentenced to only 30 days of confinement in a military stockade operated by American occupation forces, rather than in a German prison.

While serving his sentence, a brief encounter changed the course of his life. “There I met a priest, because there was no rabbi, and he opened my mind up, you know? He said: ‘If you are going to be killing them the same way that they did to you, then what’s the difference between you and them?’”

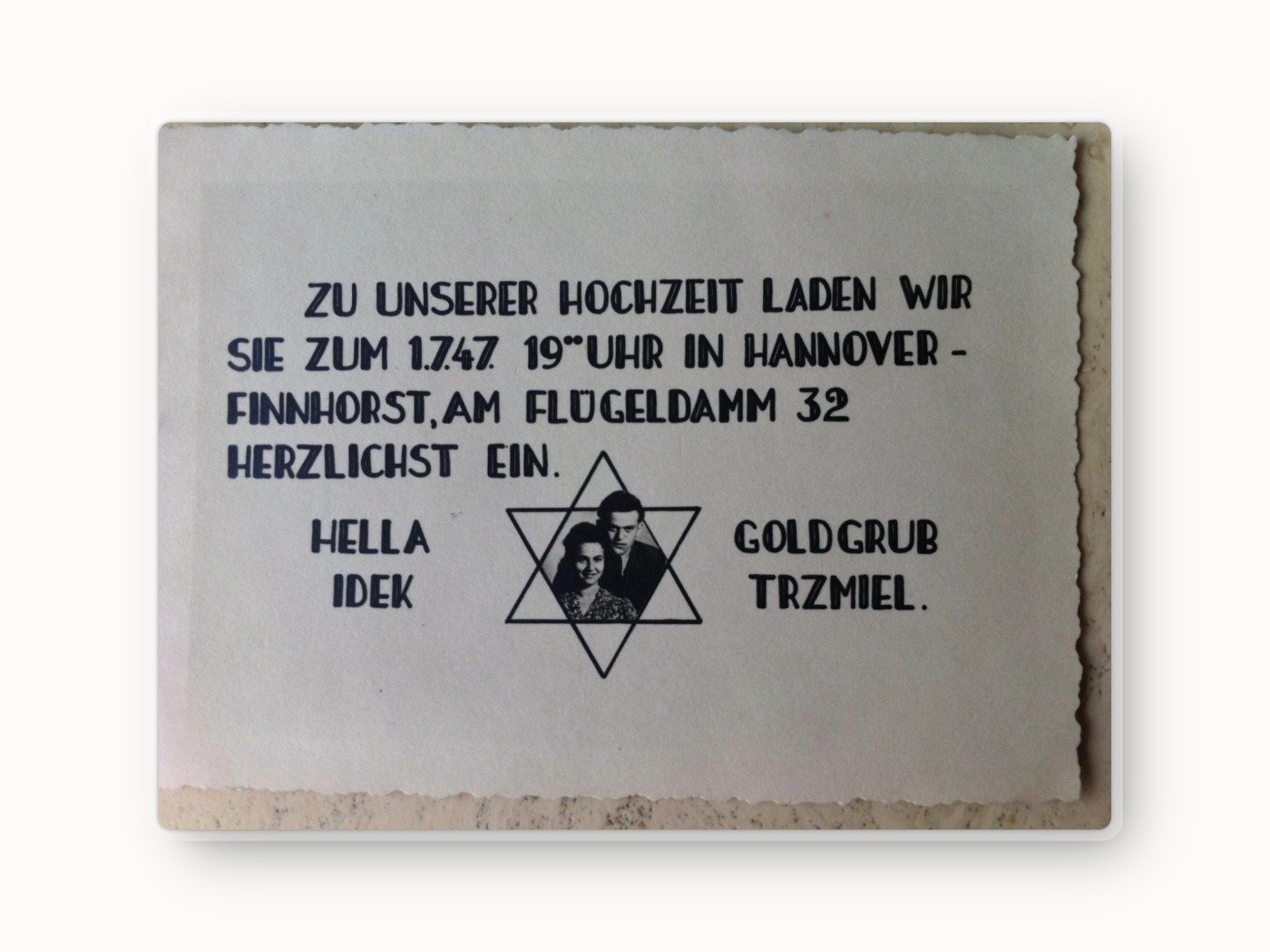

Once his sentence was complete, Idek decided that he needed to leave the past—and Germany—behind for good. In November 1947, Idek, who was in his early twenties, emigrated by ship to the United States with the help of a Jewish survivors’ charity. He had married fellow Holocaust survivor Helen Goldgrub a few months before but had to leave her behind. The couple agreed that she would follow once he had secured reliable work. By the time he arrived in New York City, Juda Idek Trzmiel had Americanized his name and become Jack Tramiel. He had no money, job, or connections but was determined to make his mark. He lived out of a shelter for Jewish emigrés, worked odd jobs, and learned English. Then, in 1948, he joined the U.S. Army.

Invitation to the Tramiels' wedding in 1947. Source: Leonard Tramiel personal collection via Archive.org."I felt I owed something to this country,” Tramiel explained later. “And I believed in paying it back."

The ‘Religion’

This idea—that a debt should always be repaid—became the first of a series of rules by which Tramiel decided to live his life. It was his philosophy that applied to everything from relationships to personal choices—and especially to business.

“Jack called his management philosophy ‘the Religion.’ ‘You have to believe in it, otherwise it doesn't work,’ he’d say,” Michael Tomczyk, who worked for Tramiel at Commodore and Atari, later remembered.

At this stage, “the Religion” was still a work in progress. In many ways, so was Jack himself. He spent four years in the U.S. Army. While in uniform, he returned to Germany, where he discovered that his mother had also survived the war and was reunited with her. On his return to the U.S., he was accompanied by his wife Helen. Thanks to his army position, Tramiel had the paperwork—and financial security—to bring her back to the U.S.

By the time Tramiel left the Army in 1951, he’d also become a father to the first of three sons. The army had given him a new set of technical skills—typewriter maintenance—that he intended to put to good use. He took a job at a typewriter store in New York but wasn’t there long. Tramiel used his army connections to secure a lucrative repair contract for the store’s owner. In return, he expected to get a raise. When that didn’t happen, he quit on the spot.

“I have no intention of working for people who have no brains,” he told the man. Then, he walked out the door.

A second tenet of Jack Tramiel’s Religion had been laid down: Only work with smart people.

With the help of veteran grants, Tramiel set up his own typewriter repair shop in the Bronx. The shop was breaking even, but there wasn’t any real scope to expand. That was when another tenet of his Religion was laid down: Always look for opportunities.

In 1955, Tramiel was selling mechanical adding machines, an early form of the calculator. They were sourced from a company known as Everest. During a conversation with one of its agents, Tramiel learned that the company wanted someone to be its exclusive importer in Ontario, Canada. Tramiel took on the contract and moved his family, including his first son, to Toronto.

In 1958, opportunity struck again. Sears was looking for a supplier for typewriters in Canada. Tramiel persuaded the company to issue him the contract, along with roughly $175,000 in advanced sales (about $2 million today). It was an extraordinary coup for Tramiel, but he faced one problem: Despite what he’d told the department store, he lacked the knowledge and manufacturing capacity to build typewriters himself.

Tramiel approached the leading U.S. manufacturers, including Royal and Smith-Corona, to see if they would help bring the typewriters over to Canada. Both firms refused to supply machines to Tramiel. They wanted him to fail so they could secure the Sears contract themselves. But Tramiel had no intention of failing. He flew to Europe to find the right manufacturing partner. In Prague, Czechoslovakia, he made a deal with a local typewriter manufacturer. Tramiel’s firm would import Czech typewriters to Canada, where they would alter them just enough to be able to rebadge the machines as domestically produced, exempting them from import tariffs.

All he needed now was a brand name for his rebadging operation. He wanted a word with a military connection, something that would sound authoritative to Canadian Sears customers, but also in the U.S. if he decided to expand there. All the good ones like “General” and “Admiral” seemed to be taken. One day, while in a taxi in Berlin, he saw a particularly stylish car in front. The name of its maker—Hudson Motor Company—was emblazoned on the trunk. So was the model. It gave Tramiel the word he was after.

Commodore.

Commodore’s rollercoaster ride

Under Jack’s leadership, Commodore was a financial success, but Jack was never satisfied. Whenever Commodore made money, Tramiel would invest it all back into the firm. He expanded existing facilities, spent more on advertising, and purchased new businesses to add to the Commodore brand, including an office furniture factory. This created periods of enormous growth, but also often left Commodore financially fragile and without significant cash reserves.

Another tenet of Jack’s religion was established: All growth opportunities must be taken, regardless of the financial burden they might place on the company.

In conversation with Tomczyk, Tramiel acknowledged that this approach was partly a result of his experiences in the Holocaust. He couldn’t trust what tomorrow might bring.

"’I live in the future,’ he told me. ‘Only the future. There's nothing else.’"

Eventually, this growth came at a cost. In the late 1950s, Tramiel was forced to sell half of Commodore to Atlantic Acceptance, the third largest non-bank lender in Canada. Then, he took out further loans from Atlantic Acceptance, which allowed the company to expand into electronics, such as radios, and office supplies. This time, the price was surrendering the chairmanship of Commodore to C. Powell Morgan, president of Atlantic Acceptance.

Then, in 1965, Atlantic Acceptance collapsed in a financial scandal considered one of the largest in Canadian history. C. Powell Morgan was jailed for financial fraud. Tramiel, too, was investigated for financial fraud, although he was ultimately cleared.

This was a financial catastrophe for Commodore. The company was heavily indebted to Atlantic, and other lenders called in their loans as well.

Tramiel frantically hunted for a new financial patron. What he got was Irving Gould.

Gould, born in 1914, was a powerful Canadian financier and owner (or part-owner) of multiple businesses around the world. Although his exact wealth in 1965 is uncertain, the lowest estimates place it in the hundreds of millions (enough to make him a billionaire, in modern terms). That wealth was, in part, built through his ability to spot financial opportunities lurking in the gray area between business activities, and the regulations and tax authorities that governed them. It was Gould who would later create a byzantine corporate setup at Commodore that would see all of its global business profits reported in the Bahamas, saving the corporation hundreds of millions in tax worldwide.

Tramiel first met Gould in the fall of 1965. The financier was a man who liked to operate in the background but enjoyed a flamboyant personal lifestyle. Tramiel was the exact opposite. He was a loud, bombastic figure who lived a frugal life. Despite their differences, both men recognized a mutual talent for business. Gould could see that Tramiel knew how to create profitable businesses—with occasional cash flow crises. Each crisis allowed Gould to take a little bit more of Commodore. Once the crisis had passed, Gould would take the money back out.

On the other hand, Gould had cash to help Commodore survive. During that first investment, he took 17 percent of the company and was appointed chairman.

This arrangement would cause Tramiel problems in the future, but Gould opened other doors. Their relationship triggered one of the most important events in Tramiel's life: his first visit to Japan.

The calculator pivot

When Tramiel visited Japan in the late 1960s, he realized that Commodore was in the wrong business. There, he saw the future. That future involved electronic calculators, not typewriters. Electronic calculators used silicon chips to carry out the same range of calculations as Commodore’s mechanical machines, but were much smaller, easier to use, and far less prone to failure.

"I made the trip to Japan and I found out the world was changing,” he later remembered.

As is often the case with the history of Commodore, why Tramiel decided to make that trip is open to question. Tramiel often claimed it was on his own volition, but Gould was a life-long Japanophile with shipping interests (and a mistress) there.

“Yeah. Irving [Gould] told Jack to get his ass to Japan,” Chuck Peddle, later one of the most important figures at Commodore, told the Computer History Museum bluntly in 2019.

Whatever the reason, Tramiel was deeply influenced by his trip. Upon his return, he pivoted Commodore to the calculator business, importing Casio calculators and rebranding them for Canadian and U.S. markets. Soon, Commodore set up factories to build calculators of its own in the U.S. These were funded by Irving Gould—in return for a little bit more of the company.

For five years, Commodore flew high in the calculator business. Tramiel bought silicon chips from domestic manufacturers such as Texas Instruments, one of the largest chip makers in the world, and turned them into calculators, selling the finished product at considerable profit. He wasn’t the only one doing this. In Albuquerque, an ex-Airforce officer named Ed Roberts had founded a company called MITS that was doing the same.

Both men were generating large profits, but Texas Instruments was watching. Texas Instruments decided to start making calculators itself, and because the company made its own chips, it could make the machines cheaper than anyone else. By 1974, it was selling almost 30 million calculators a year, destroying the market for third-party calculator manufacturers like Commodore and MITS almost overnight.

In Albuquerque, Ed Roberts reacted by accepting his defeat. In what would prove to be a key moment in the history of computing, he pivoted MITS to produce a personal computer known as the Altair 8800. Tramiel took a different lesson from the experience. He added a new tenet to his Religion: Always control the means of production.

"I had to decide a way I could not depend on the outside. How to become vertically integrated."

Chip manufacturing

Being vertically integrated meant Commodore, like Texas Instruments, had to make its own chips. But chip manufacture was highly specialized. It wasn’t something you could start doing overnight. So Tramiel, ever ruthless, decided to take over someone else’s chip business instead.

That business was MOS Technology. Founded in 1969, MOS had perfected low-cost chip manufacture by the mid-seventies. At the beginning of 1975, it stunned the computer industry by announcing the launch of the 6502 central processing unit (CPU) chip for just $25. Meanwhile, rivals Motorola and Intel were selling their own equivalents for $179.

MOS Technology seemed to be on the verge of a bright future, but the company was in deep financial trouble. In part, this was because of a lawsuit from Motorola. It was also because MOS was sitting on a huge pile of unpaid invoices from calculator manufacturers—most notably Commodore, which was in deep financial distress due to its competition with Texas Instruments and Tramiel’s financial strategies.

Tramiel sensed a way he could save Commodore. Instead of paying his bills, he returned to Irving Gould. Gould injected sufficient capital to allow Tramiel to buy the near-bankrupt MOS. For another slice of Commodore, of course.

Overnight, Commodore became a major manufacturer of chips. Tramiel had vertically integrated his production line. He also took something else from MOS. The deal was conditional on one man leaving MOS and working directly for Tramiel at Commodore: the designer of the 6502 chip itself, Chuck Peddle.

The first Commodore computer

“The 6502 was specifically designed to be the universal solvent. It's just enough, and it's simple enough, and it's cheap enough that you can use it for anything,” Peddle told the Computer History Museum.

The Altair 8800 had proved that a market existed for low-end computers, but Peddle was one of the first to spot the market’s true potential. While at MOS, he designed the KIM-1, an extremely basic computer using the 6502 to prove it could be done.

Peddle had caught Tramiel’s attention not because of the KIM-1, but because Tramiel wanted a way into a growing off-shoot of the calculator market—chess calculators, or machines that would play you at chess. Once Peddle joined Commodore, however, he suggested to Tramiel that they go one further. Peddle pointed out that the Altair 8800 released by MITS for the computer hobbyist market had shown that there was demand for personal computers. He told Tramiel that they shouldn’t waste time with calculators. Instead, they should build a computer based on the 6502 chip.

“I can build a personal computer that can sell,” Peddle told Tramiel.

Tramiel had no real understanding of what a computer was or why people might buy one. But Peddle was a smart man offering up an opportunity. That fulfilled the two tenets of Tramiel’s Religion—work with smart people and look for opportunities. So he told Peddle to do it.

Peddle had talked briefly with Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak when they were working on the Apple computer. He knew the two men were hoping to use the 6502 chip in their next machine, the Apple II. So he suggested that they let Commodore buy them out. Jobs was excited by the possibility.

“Steve [Jobs] started saying all we want to do was offer [Apple] for a few hundred thousand dollars, and we will get jobs at Commodore, we’ll get some stock, and we’ll be in charge of running the program,” Wozniak said later.

Jobs and Tramiel sat down to negotiate. Overconfident, Jobs told Tramiel they wanted $150,000 (about $850,000 today) for Apple. Tramiel was prepared to back Peddle’s idea, but spending that much money on a company based out of a suburban garage seemed ludicrous. Jobs’s attitude also annoyed him. So he walked away from the negotiations, and told Peddle he had three months to assemble a team and design the computer himself. He wanted it ready for the January 1977 Computer Electronics Show (CES).

Peddle tried to explain that this was too short a deadline, but Tramiel waved his objections away and added a new tenet to the Religion: Give smart people a clear deadline and they’ll somehow figure it out.

Peddle set about designing and building a bespoke Commodore computer. At the time, MITS’s Altair 8800 dominated the hobbyist market, while companies like Vector Graphic were making machines like the Vector 1 for small and medium businesses. Both machines required users to understand complex machine language if they wanted to create their own programs. Peddle believed that this was a mistake. He concluded that the first successful mass market computer would be one that people felt that they could program themselves. He designed a machine that came with a keyboard and monitor. Then, he set about sourcing a human-readable programming language. He decided that the language that best met that requirement was Microsoft BASIC.

Peddle approached Bill Gates at Microsoft and requested a version of Microsoft BASIC for the 6502 chip. Gates was skeptical. He thought the chip would use up so much processing power it would cripple the machine, but agreed to do it anyway. Peddle suggested a contract where Microsoft would receive a royalty for each machine sold. Gates laughed him off. He didn’t think the thing would sell, and he wanted the money upfront.

Rather than charge Commodore a small fee for every machine they sold with BASIC on it, Gates offered a perpetual license. In return for a fixed fee, Commodore would be given a version of BASIC that it could install on as many machines as it liked, for as long as it wanted.

Commodore and Microsoft never revealed how much the deal cost, but most estimates have placed it at about $25,000. Commodore would go on to use that version of BASIC for every single Commodore designed and released during Tramiel’s time in charge—somewhere north of 15 million machines. In modern terms, the deal cost Microsoft more than $400 million in lost revenue. Bill Gates never made a fixed-fee deal again.

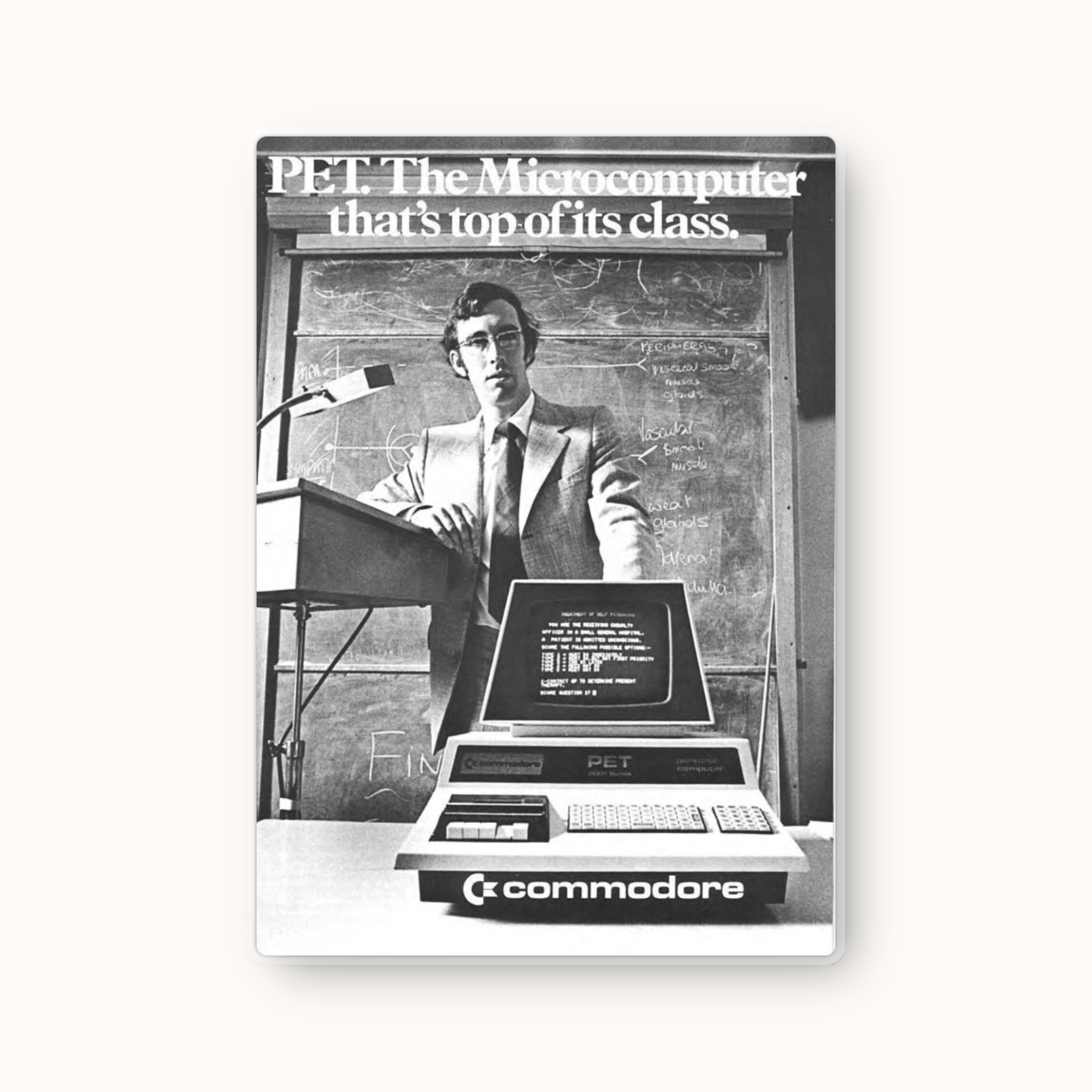

At CES 1977, the Commodore PET was revealed to the world, wrapped in a stainless steel case that was made by a filing cabinet factory that Tramiel owned in Canada. PET didn’t stand for anything. It was just a pun on the popularity of pet rock toys at the time.

Magazine advertisement for the Commodore PET, emphasizing its potential in education, in 1978. Source: Courtesy of the author.The machine was an instant hit. The only problem was that Commodore did not have the money to set up the manufacturing capacity necessary to bring it to market. Peddle raised this concern with Tramiel, who laughed it off.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.50.43_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Such a great story. The first computer I ever encountered (aged 10) was a PET. I was hooked, and I absolutely loved my VIC-20. Amazing what could be done with just 3.5KB RAM! Jack Tramiel changed my world.

My home computer trajectory was PET (borrowed from my Dad's work), Acorn Atom then BBC Micro. I had no idea how quickly Commodore produced their models, nor that they bought MOS. Excellent article!