If history is written by the victors, Lore Harp McGovern should have volumes devoted to her contributions to the personal computing industry. In the mid-1970s, from her suburban California home, Harp McGovern—a housewife and mother of two—began assembling memory boards and other computer expansions to sell to the growing hobbyist and business markets. With her friend Carole Ely, she grew their company, Vector Graphic, into a major manufacturer of microcomputers, eventually taking it public before Big Blue—IBM—muscled into the market. In the latest installment of his column The Crazy Ones, Gareth Edwards tells the untold story of one of the last remaining original founders of Silicon Valley.—Kate Lee

London. 1981. A young, smartly dressed woman watches from the sidelines as a stage is prepared. Everyone is there to hear about a hotly anticipated IPO out of Silicon Valley. An investor approaches the woman and asks for a coffee refill from the table behind her. Her train of thought broken, she looks up at him. For a second, she holds his gaze. Then she turns and pours him a coffee. A few minutes later, the host announces that the CEO is ready to speak.

Tucking her short brown hair behind her ears, the same young woman straightens her suit and walks confidently up onto the stage. A murmur of surprise spreads across the room, which soon gives way to polite applause. She nods in acknowledgement, her eyes scanning the audience, searching.

“My name is Lore Harp, CEO and founder of Vector Graphic,” she says, her accent a mix of German and Californian. She locks eyes with the investor who asked her to refill his cup. “Sir, do you need me to get you any more coffee?”

The crowd looks at the embarrassed investor. He shakes his head.

“Good,” Lore Harp says with a thin smile. “Let’s continue, then, shall we?”

This is the story of Lore Harp McGovern, founder of Vector Graphic. With her friend Carole Ely, she launched a multimillion-dollar computer company from her suburban home and became one of the most important founders of the microcomputer age. It is based on contemporary accounts in publications such as the Harvard Business Review, Interface Age, Kilobaud, Time, and the Los Angeles Times, as well as books such as Women, Technology and Power by Marguerite Zientara; Future Rich by Jacqueline Thompson; and The Untold Story of the Computer Revolution by G.H. Stine. It is also based on the words of Lore Harp McGovern herself.

‘You can do anything you want’

Like many of Silicon Valley’s pioneers, Harp was an immigrant. Born Lore Lange-Hegermann, she grew up in Bottrop, Germany amid World War II, where she shared a bombed-out building with her parents and grandfather, Hermann Lange-Hegermann.

Lange-Hegermann had been a businessman and politician during the pre-war Weimar Republic, but the rise of Hitler and the war had cost him his political career and much of his business empire. He believed in the importance of a proper education for all of his children and grandchildren, regardless of gender. As a result, Lore grew up watching her aunt become a successful lawyer and her father take over what remained of her grandfather’s businesses.

Lore’s grandfather was her biggest influence. “I remember, as a seven-year-old, getting a little book from him,” she recalled later in an interview with the Computer History Museum. “In my child’s mind’s eye, it was gigantic. And it was a photographic book of people from all over the world in their native costumes, their traditions and all this. And I was so enthused about the book that I said, ‘I will see all these people!’”

“You can do anything you want,” her grandfather responded.

What her family hadn’t entirely grasped was just how determined Lore was to achieve this goal. Smart and observant, it hadn’t taken long for her to spot that reality didn’t always match the ideal. Her mother was a talented photographer and had studied the subject in college, but society expected her to become a housewife, which she did. So while Lore studied hard, she also watched for an opportunity to do something different. In February 1964, one of her friends pulled out of a planned six-month exchange visit with an American family. It was the opportunity Lore had been waiting for. She went instead.

A land of opportunity

On February 8, 1964, Lore Lange-Hegermann arrived in Santa Cruz, California. She was 19 years old and had promised her family that she would only stay for six months.

Six months later, to her parents’ surprise and disappointment, Lore sold her return ticket to West Germany and hitchhiked to Mexico. After that, she headed to San Francisco. When her tourist visa expired, she became undocumented, unable to officially work. She crashed in a shared house with four other women and took off-the-books jobs to pay rent and survive, while immersing herself in the growing sixties counterculture.

During this time, she met Bob Harp. Bob was a young computing researcher and engineer whose talents had secured him a well-paid role at a prestigious research institute in Germany. On his return to the U.S., his path crossed with Lore’s. She was attending a friend’s party when a British sports car roared up outside. It was Bob.

Bob was as outgoing as he was brilliant, and the two soon fell into conversation. The fact that Bob had broader horizons than most of his peers and spoke fluent German, thanks to his time in Europe, also helped. He made an instant impression on Lore, and she on him. It wasn’t long before they began dating and fell in love. When he was offered a research job at the California Institute of Technology, she agreed to go with him. For the next year, the pair enjoyed living a bohemian life in Los Angeles, until the inevitable happened—immigration services caught up with Lore. Threatened with deportation and summoned to an interview, the couple hatched a plan.

“I put on my little black shift dress,” Lore later said. “My hair was down. I put it in a big bun. I put on my pearl necklace, my father’s gold bracelet, my grandmother’s ring. I sat there like Miss Prim and Proper. And we said, ‘Oh, we just got engaged, and we’re getting married.’”

And they did. Lore Lange-Hegermann became Lore Harp. “We found some minister in our neighborhood, and then we went to McDonald’s and had a hamburger.”

The gilded cage

While Bob had worked at Caltech, Lore was able to immerse herself in the flourishing local art community. But over time the gears of his career began to turn. In the early seventies, Bob was offered a better-paid aeronautical research role at Hughes Research Laboratories, which he accepted. For Harp, this meant leaving vibrant Los Angeles for a more traditional suburban life in Westlake Village, California. “We moved from there to way out in the boonies,” Harp recalled. “Westlake Village which is…oh my God.”

By 1975, this lifestyle had begun to take a toll on her mental health. Harp had stayed in America to escape a future where her only option was to be a housewife.Yet in Westlake Village, this was the only role it seemed possible for her to play. While Bob worked, she was required to manage the home and join the various women’s groups and their activities like charity fundraisers and dinner parties—obligations expected by her community and Bob’s employer. To try and prevent this from taking over her whole life, she started studying anthropology. But then she became pregnant with their first child and was forced to abandon her studies. A second—another daughter—followed two years later. When the children were three and five, Harp tried to pursue school again, this time hoping to follow in her aunt’s footsteps and become a lawyer. But law school was not friendly to young mothers.

“My husband was not the kind of person who would take over half the chores while I studied, even though he was otherwise supportive,” she said. Forced to quit, Harp felt frustrated and isolated. The social activities that seemed to provide a sense of value and purpose for many of her neighbors just didn’t feel satisfying for her.

“I was 32 at the time, and I felt…‘My God, suddenly I’ll be 40, the children will be gone, and where am I going to be?'”

The product

Harp first met Carole Ely while they were waiting to pick up their children from school. Ely had started a promising career as a bond trader when marriage and children intervened. Now, like Harp, she was stuck living the life of a Westlake Village housewife. She, too, felt caged.

The duo talked about starting a business together. Their first idea was a travel agency. However, the travel industry in California was one of entrenched interests—when it came to securing partnerships and permits, who you knew mattered just as much as how good your product was. Networking required membership of the kind of business and social clubs that would never allow two women like Harp and Ely to join.

Then, in January 1975, Popular Electronics published a picture of the Altair 8800 on its cover. Bob Harp, like many who worked with large computers in their workplace, had never imagined that he might one day own a machine of his own. He placed an order for the Altair, which was billed as the world’s first mass-market “microcomputer.” When the machine arrived in kit form, Bob quickly assembled it and it became one of his obsessions. The Harp house was soon filled with pamphlets, newsletters, and how-to guides about microcomputers, and Bob discovered, to his delight, that the Altair’s creator Ed Roberts had built it around a principle of “open architecture” via its S-100 expansion socket. Anyone could create memory boards or peripherals that could expand the functionality of the machine . A few third-party expansions were already on the market and more were being released regularly, but Bob decided it would be more interesting (and a fun test of his skills) to design his own expansion board. Over the course of a few months, he created a board for his own use, one that would double the amount of RAM in his Altair from 4K to a mighty 8K.

While Bob was at work, Harp would read the computing materials that littered the house. Dinner table conversations would routinely include discussion of the latest trends in technology. Through a form of osmosis, she became versed in the growing computer industry herself. “[Bob] was reading tech publications all the time, and I kind of read them as well, and looked at them, and saw what was going on,” she said.

Harp decided that Bob’s 8K RAM board was the opportunity that she and Ely had been waiting for. They would make and sell them from home. In return, Bob would receive a royalty payment on every sale. She called her prospective business partner and asked her if she wanted to team up and sell memory boards.

“Sure,” Ely replied. “What’s a memory board?”

Two days after that phone call, Lore Harp and Ely attended the Southern California Computer Society’s monthly show. They were there to scout out their potential market. They watched vendors try to sell bags of chips and parts for memory boards and other expansions, often with poorly composed hand-written instructions on how to build them. The whole operation seemed distinctly amateur, yet it seemed to work. Attendees would hand over bundles of money—sometimes as much as $1,000 (about $5,000 today)—in exchange for these products.

Two days later, on August 23, 1976, Vector Graphic was incorporated. Its head of marketing was Carole Ely. Lore Harp was the CEO.

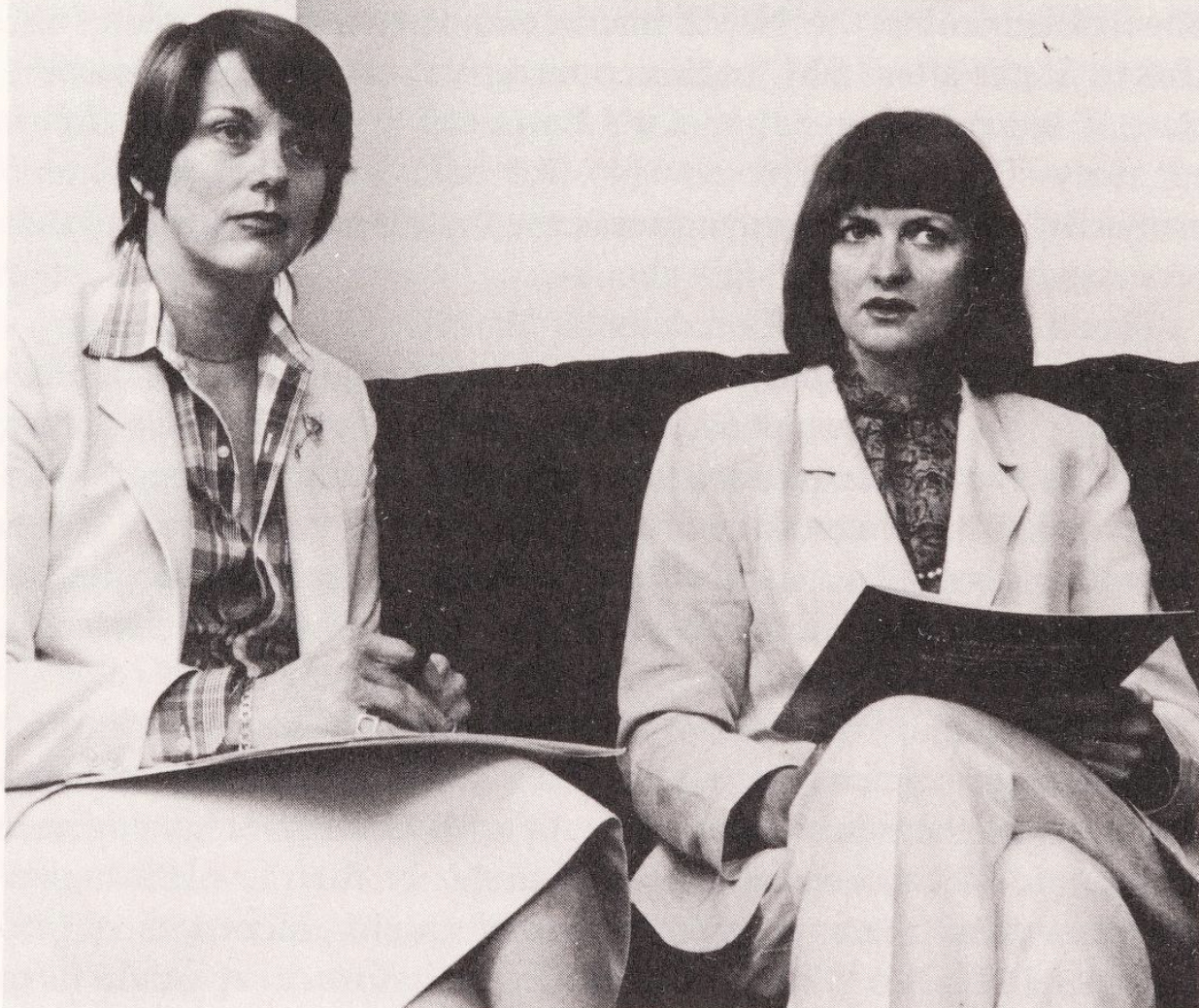

Carole Ely (left) and Lore Harp. Source: Vector Graphic.

The deal

“It’s Lore Harp from Vector Graphic. We have a new memory board and need about 50,000 chips.”

Harp was seated in the family room of her Westlake home on the phone with a sales representative at chip manufacturer AMD. The company was one of a small number of independent U.S. chip manufacturers that were prepared to supply third parties. Harp and Ely needed these chips so they could package them into kits in Harp’s house and sell them as memory board kits.

“Oh!” The sales representative on the other end of the phone sounded keen. “I’d be happy to come to your office to discuss it.” Harp looked around the room and across to the kitchen beyond, where a large pot of stew was cooking on the stove.

“We’d love to meet you in our office, but we’re in the middle of moving,” she replied, thinking on her feet. Harp told the representative they were in Westlake and suggested they meet at the Westlake Inn. The sales representative agreed. After calling Carole and telling her the news, Harp called Bob at work.

“You’ve got to get home from Hughes,” she told him. “You’ve got to be here at a quarter to five to care for the kids. We have to go meet a guy from AMD.”

The memory of that first meeting was seared into Harp’s brain. “He had these little monogrammed cufflinks and that aftershave everybody had. Some Old Spice thing,” she remembered about the salesman later. “And he gave us this up-and-down look. I never forget this.”

The three of them sat down in the hotel’s restaurant area and tried to negotiate a deal. Harp told the man from AMD that they planned to manufacture memory boards and sell them to the growing hobbyist market. The salesman nodded along, then gave them a price. It was far too high. “He didn’t even know what an Altair was,” Harp said. As a result, he didn’t believe their assertions that there was a large enough market for their product to make a discount worthwhile. They refused AMD’s terms.

Not to be deterred, Harp called Fairchild Semiconductor, another major chip manufacturer. Once again, it led to a meeting at the Westlake Inn.

“You know what,” the Fairchild representative replied after Harp had explained their plan. “I’ll help you.”

Now Harp took her biggest gamble. They didn’t have enough money to pre-pay for the chips, so she decided to be honest.

“We will pay within 30 days because we cannot afford to prepay,” she told him. Harp knew that they’d need to sell enough boards first to cover the cost. “We promise we’ll pay in 30 days or before.”

The Fairchild man was silent. Then he laughed. “You know what? I trust you.”

They shook hands and went their separate ways. A few weeks later, there was a knock on the Harp family door. When Lore opened it, a man named Dick Kirkpatrick introduced himself. He explained that he was their Fairchild distributor and pointed to the boxes of chips in the back of his rental car. Harp helped him carry the boxes into the back bedroom that they had begun converting into an assembly space.

The sell

Stan Veit had just opened up his computer store one autumn morning in New York when the phone rang. It was a woman calling from California. She wanted to sell him some memory boards.

“I listened because a woman selling computer equipment was indeed a novelty,” he wrote later. “After speaking with her, I found out that her name was Lore Harp.”

Veit didn’t know it, but he was about to be subject to a sales pitch created by Carole Ely to make Vector stand out.

Harp told Veit that the Vector boards were not only superior to anything else on the market—they were cheaper as well. She made Veit a simple offer.

“She would ship me two boards, and if I liked them, I would call her and she would ship me six more and I would pay cash on delivery for the six,” Veit recalled. “If I didn’t want them I just had to send her boards back. Well, that seemed like a fair offer, so I agreed.” When the boards arrived, they were as good as Harp had claimed.

Veit made the call. “Thus, I became a dealer for Vector Graphic, a company run by two women,” he wrote later.

Veit wasn’t the only one. Harp and Ely systematically went through computer hobbyist magazines like Byte and Interface Age, which were full of advertisements from dealers like Veit. It was from these computer dealers that most hobbyists purchased their microcomputers and parts, so the Vector Graphic team targeted them aggressively. They would call them and pitch the same arrangement that they had offered Veit. By October 1976, orders were flooding in. Harp and Ely’s product wasn’t revolutionary, nor were their boards significantly cheaper than their rivals, but their approach to the process of sales and ordering was more professional. This also extended to the board kits themselves. The pair hadn’t forgotten the poor-quality instructions and packaging they’d seen at computer fairs when starting out. They put extra effort into making sure that the packaging for their own boards was of a high quality, providing clear instructions for assembly, and even color-coded their chips. Overall, Vector’s commitment to high standards made them stand out.

By the end of the year, they were almost overwhelmed with orders for their memory boards, with demand starting to exceed the number of kits the two women could assemble themselves at Harp’s home. They were also attracting neighborhood attention. It was hard not to. Every weekday morning, Bob Harp would depart for work and Lore would take the children to school. Shortly after, Lore would return home and Ely would knock on her door.

The rest of the day would see a steady stream of men in suits visiting the house. A short while later, they would leave. It would stop when Lore left to pick up the children and Bob got home. The men were computer parts dealers, but the neighbors didn’t know that.

“I think our neighbors thought we had a brothel going,” Harp said.

Eventually Harp’s next-door neighbor, Jean, grew too curious to remain silent. She knocked on the door and asked what they were up to. Harp invited her in. Jean was stunned by the operation. The rear bedroom and family room of Harp’s house had been converted into a production line for memory boards and board kits. Boxes of chips and parts were stacked on the floor, while the table was covered in fruit bowls into which the correct chips for each board had been carefully sorted, ready to be packaged. In the kitchen, salesmen helped themselves to coffee while discussing orders with the women. Toward the end of the afternoon, local high school students would arrive, paid by Harp and Ely to help with packaging and distribution. Watching, Jean admitted she had never had a job, although she had always wanted one. After a brief discussion, Harp and Ely told Jean that they were expanding and offered her a job as their receptionist. She became one of their first full-time employees. Forty years later, Harp would still vividly recall the joy of giving Jean her first ever paycheck.

“It…it was just great,” Harp said, a smile on her face.

By December 1976, Harp and Ely had built Vector Graphic into a million-dollar company. In 1977, Harp decided they should go one step further: They should release a desktop microcomputer themselves. This would go from a company oriented around building add-ons for other company’s machines to making machines themselves.

The Vector 1

Harp persuaded Bob to leave his job at Hughes and join Vector Graphic full time. Harp and Ely had already employed a number of engineers to design parts, but building a computer would require someone to manage them and create an overarching design. Bob possessed the right skills and vision to do this.

The type of computer the company would build was determined by a growing demand for business machines that had been identified by their dealer network. The pair had a reputation for treating the dealers that sold Vector products fairly, so they were happy to be regularly canvassed for their opinion on what products would sell. Vector had an advantage over its competitors when it came to market intelligence. Vector’s dealers reported that their clientele was expanding. The hobbyist market was still the primary driver for sales of first-generation computers like the Altair, but small-to-medium-sized businesses were becoming interested in owning a microcomputer to use for word processing, accounting, and other business-related tasks. Unlike the hobbyists, they were often leaving stores empty-handed.

This wasn’t due to fears over price—quite the opposite. These buyers were prepared to pay more than $3,000 (roughly $16,000 today) for the right machine coupled with the right hardware add-ons or business software. It was that they wanted a microcomputer that was reliable, powerful, expandable, and pre-built—unlike hobbyists, most businesses had no desire to assemble their own machines from a kit. It also wouldn’t hurt if it was something that could serve as an office centerpiece around important clients. A machine that ticked all these boxes didn’t yet exist. The market was machines like the Altair or Apple at the low end or expensive, room-sized computers by IBM or others at the high end. There was nothing in between, so Vector decided to fill that gap.

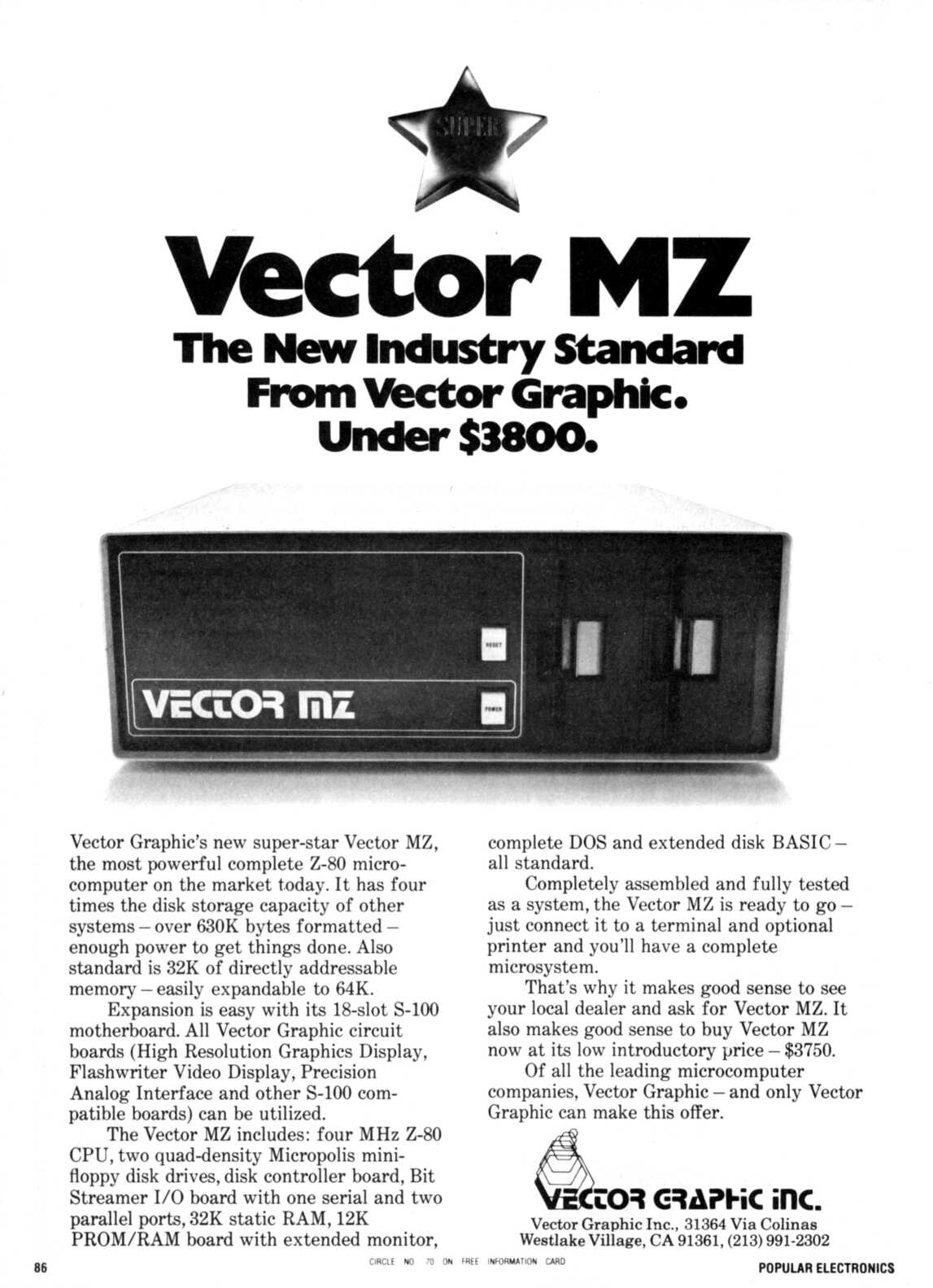

At the 1977 West Coast Computer Faire, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak set the home computer world abuzz with the announcement of the Apple II, a pre-built machine for home users. Just a few booths down, Lore Harp and Carole Ely did the same thing for businesses with the announcement of the Vector 1, designed by Bob Harp. In terms of CPU and RAM, it wasn’t anything special, launching with the same specifications as the Altair 8800. What differentiated it was that it could be easily expanded—well beyond the limits of the Altair. It also came pre-built.

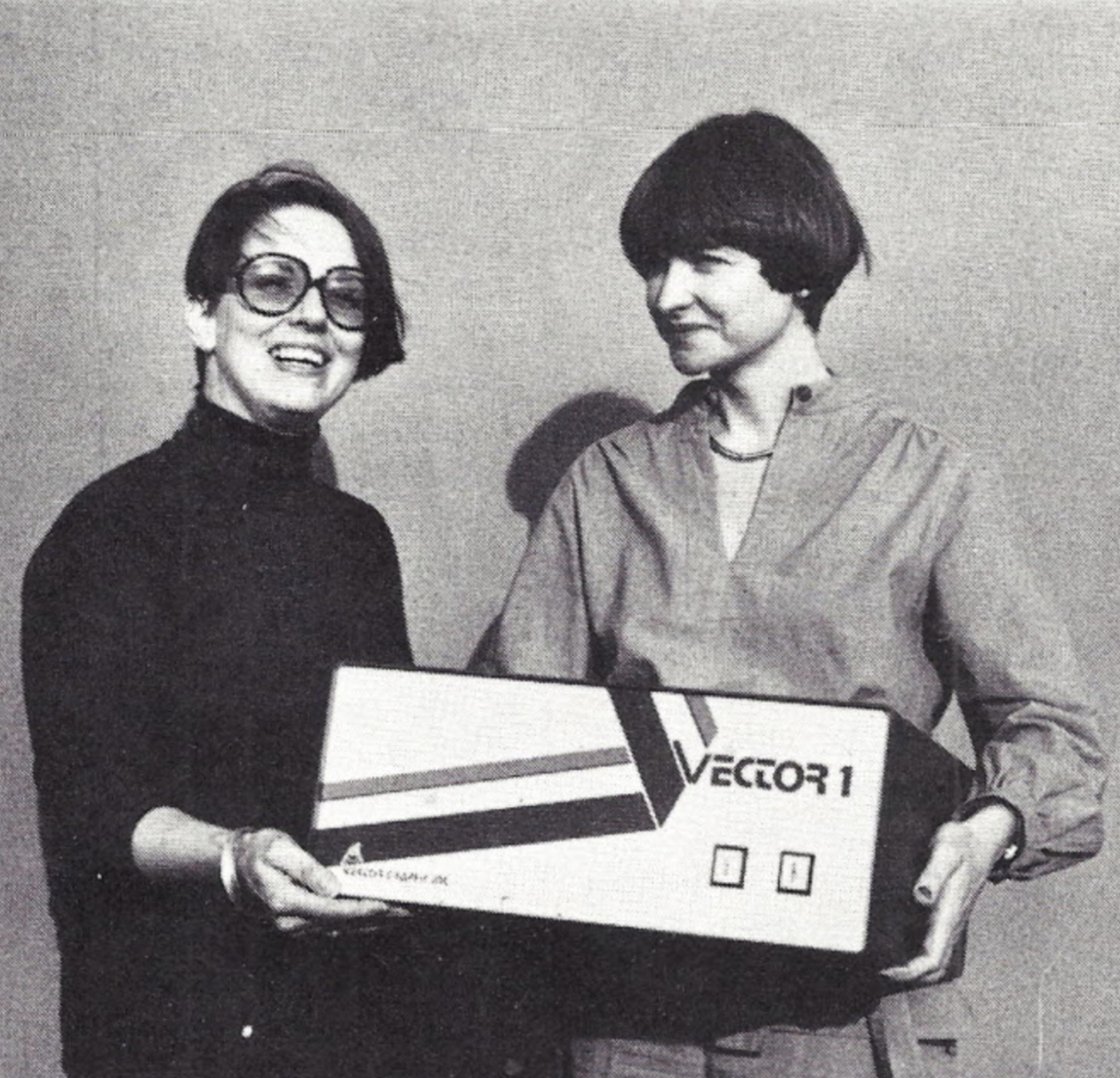

Carole Ely (left) and Lore Harp holding a Vector 1. Source: Vector Graphic.“Maybe people are really interested in having a computer that doesn't have all the switches,” Harp told an excited Personal Computing World journalist. “Maybe it’s a little beyond the hobbyist who likes to fiddle with all that and likes to see everything work.”

The Vector 1 was a no-nonsense, ready-to-use computer designed for businesses that wanted a machine that would just work. It also had style, featuring a sleek metal case with rounded corners. It was even available in four colors—burnt orange, dark green, black, and beige. “It was not Apple that did colors first,” Harp remembered later.

“The folks at Vector have managed to come up with a rather slick-looking entry into the market,” Kilobaud Microcomputing wrote. “And, it’s all theirs.”

Other reviews of the Vector 1 were equally impressive. So, too, were those for the Vector 2—a machine that kept to the same principles but was faster and had more RAM—that followed soon after. Together, the machines pushed Vector Graphic to the top of the second tier of microcomputer manufacturers that almost exclusively focused on business customers. Companies like Apple and Commodore could boast larger unit sales if figures for both the business and home markets were combined, but when it came to more expensive machines for medium-sized businesses, Vector was the dominant player. By 1980, it was achieving $25 million (about $95 million today) in annual sales. The company that had been started in Harp’s converted back bedroom was now a well-known brand within the computing industry.

Wall Street also began to notice.

From the ground up

It wasn’t just the functionality of Vector’s machines that impressed the business market. It was also that they reliably worked.

In customer surveys of the time, Vector Graphic consistently outperformed Apple, Commodore, Tandy, and others in terms of customer satisfaction among business users, largely due to reliability. Lore Harp had mastered running microcomputer production lines, something most other computer startups struggled with. Under her leadership, Vector rarely suffered any workforce issues, and the quality of output from the production lines themselves was high. Her success wasn’t just due to her eye for detail. It was also because she recognized that production is, fundamentally, about people.

In an era in which production-line staff was largely treated as unskilled labor and corporate benefits were reserved for the C-suite, Vector Graphic bucked the trend. When the company hit its first $1 million sales month, Harp closed the factory and took all 500 employees out to play baseball and drink beer. The company also paid well. It even had a daycare and offered home cleaning services to employees who were struggling to balance household responsibilities with their work.

These benefits did not go unnoticed in the trade and business press, nor that, as a result, Vector had a higher-than-average number of female employees. In interviews, magazines would ask if Harp’s approach was intended as some kind of feminist experiment. Alternatively, they would ask if it was evidence that female CEOs managed more emotionally than strategically—often with the implicit accusation that the company benefits were a sign of weakness. Harp’s answer was always the same: These benefits and policies were in place because they made economic sense.

Harp’s philosophy was made clear when Vector went public in 1981. In the first meeting with the IPO’s prospective underwriters, she dropped a bombshell—she wanted every Vector employee to receive stock options.

“That guy in assembly who puts in the last screw? If he is really mad, and he doesn’t do it properly, and Quality Assurance misses it, it’s not just the guy back there who hears about it. It’s the VP of sales,” Harp explained. “Because soon it is sales going down because suddenly you’re no longer delivering quality product. Everybody is deserving, not just those of us sitting at the front office.”

She was told it wasn’t normal. Share options for senior staff was fine, but offering them to the entire staff would harm the value of the offering.

Harp wouldn’t budge. “Well, you’ve got five minutes,” she told them. “We must have a deal at the end of that time, or we walk.”

The underwriters protested again.

“Okay,” Harp said calmly, looking at her watch. “Well, that’s 30 seconds gone.”

After a frantic discussion, the underwriters agreed to find a way to make it work. In the end, Vector’s staff received stock options based on their time at the company, priced at $1 per share. When the IPO was successful, these shares increased in value by a factor of 13.

“People couldn’t believe it,” Harp said later. “They were thrilled.”

The IPO also made Harp the second-ever female founder to take a company public on the Nasdaq stock exchange. Fellow Silicon Valley tech entrepreneur Sandra Kurtzig beat her by just a few days. Harp didn’t mind. Kurtzig was the founder of ASK, a software company focused on business productivity applications. As the two most prominent female founders in the industry, they had become good friends and business allies.

Although the IPO would represent a major achievement for both Harp and Ely, running Vector was taking a toll on their marriages. Ely’s husband had tolerated her role at Vector as an outlet for her boredom, but as she continued to invest more of her time in the company, their relationship began to deteriorate. For the Harps, cracks were also appearing. Bob had also initially seen Vector as a side project for Lore Harp, and his direct involvement created further problems when the two began to hold different opinions on how the company should be run. He was resentful of the level of attention she received in the press, feeling it diminished his own role at Vector.

The Ice Maiden

In the beginning, both Harp and Ely were treated as a curious novelty by the rest of Silicon Valley. Their impressive range of products allowed them access to the right circles and markets, but that often came at a price. At best, they were treated with a sort of benign paternalism by competitors that Harp was often all too happy to exploit. Often, the first time a competitor realized how ruthless she could be was when they discovered their customers were now Vector’s customers instead.

Deals and product demos often took place in hotel rooms during industry shows or on sales tours. Unfortunately, Harp and Ely were often left having to deal with attempts at abuse or exploitation.

“They either just loved you, or they were trying to be after you,” Harp said later. “One guy actually got slapped. I said, ‘I’m here for one purpose only.’”

As Harp climbed higher within American industry, the paradigm started to shift. Senior figures within other companies began to resent her presence at the top of the tech pyramid. What had begun as an unthreatening story of two housewives running an odd little business became one instead of two women successfully building and expanding their empire. To many, this didn’t seem possible, and articles of the time suggested that Harp’s husband Bob played a larger role than he actually did. By diminishing the role of the two women in the success of their own company, readers were reassured—whether purposely or not—that behind every successful woman, there must be a man.

This attitude wasn’t universal. There were those who saw Harp’s skills clearly for what they were. In late 1980, it was Harp—and Vector—who Adam Osborne approached while looking for a manufacturer for his revolutionary portable computer. Osborne was making the jump from writing about computers to designing them. He knew that manufacturing his new machine—the Osborne 1—would be difficult and complex, so he wanted it to be made by the best. In his mind, the best was Lore Harp. Harp was skeptical and wanted to wait until Osborne had a production prototype. Unwilling to wait, Adam Osborne pushed ahead on his own.

After Vector went public in August 1981, the negative perception of Harp held by some executives only grew stronger. Female business icons were allowed, as long as they followed the unwritten rules and remained quiet and humble. Harp was proud of her company and her success, and was happy to call out individuals who treated her poorly, as she had done at that London meeting for Vector’s IPO.

Soon, she was referred to as the “Ice Maiden” within the industry. Early in 1982, a female employee wrote to Harp, congratulating her on her success. However, the employee expressed her dismay at some of the things she would hear from male industry figures when she mentioned that she worked at Vector. She told Harp that one man had complained to her about “the awful bitch who was running the company.”

“I sent a nice note back,” Harp remembered later, “and said I especially enjoyed the comment about this bitch running the company because that poor guy is either so jealous or he’s so stupid that he doesn’t have anything else to talk about, and I must be terribly important in his eyes.”

Long before the phrase was coined, Lore Harp was busy living rent-free in many male executives’ heads.

The breakup

Harp and Ely’s success came at a cost. By the end of 1981, Carole Ely was divorced; her husband was unhappy with how much of her time was occupied by her career. Lore and Bob Harp had already effectively separated by the end of 1980, and the possibility of a divorce was even declared as a business risk in the company’s IPO documents. Any faint chance of reconciliation ended with the positive press Vector received after the company went public. Much of this focused on Harp’s leadership role and impact on the company’s success, including an interview in Time magazine. Bob, annoyed at the attention his then-wife was receiving, burned a number of copies of Inc. magazine—which had featured Harp on its cover—in front of her.

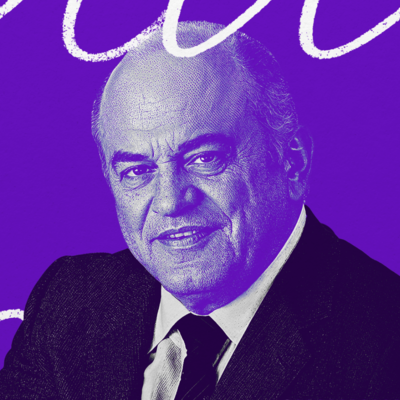

Official divorce proceedings began not long after, eventually concluding in the summer of 1982. In the end, Harp would be divorced for only a single day. She had already begun a relationship with the man who would become her second husband—publishing mogul Pat McGovern. She became Lore Harp McGovern. They proved to be a good match, enjoying their time together but respecting each other’s boundaries. The marriage would last until McGovern’s death in 2014.

‘Big Blue’ awakens

Adam Osborne was not the only person in Silicon Valley impressed with what Lore Harp McGovern had built at Vector. Just before she took the company public, a man named Don Estridge led a delegation from IBM to pay her a visit. Estridge indicated that IBM was thinking about making a small move into the microcomputer market, and suggested that Vector could supply computers for IBM to badge and sell under an original equipment manufacturer (OEM) arrangement. Rather than designing and selling its own microcomputer, IBM would be happy to confine itself to purchasing stock from Vector that it would sell—with a mark-up—as IBM products.

“Let me get this straight,” Harp McGovern asked him. “You are a $25 billion business. We’re a $25 million business. And you are interested in potentially buying OEM products from us? That seems like a highly unlikely proposition.”

Estridge insisted it was true, and Harp McGovern played along. Estridge left with a number of Vector machines as samples. Harp McGovern was smart enough though to know what this really meant: IBM was building a microcomputer. She called an emergency meeting of her senior executives.

“We have one year, if that,” she said. “The world is going to change.”

Vector Graphic knew that if IBM (“Big Blue” to its friends and enemies) entered the market, it would target business clients—Vector’s bread and butter. This couldn’t have come at a worse time. Bob Harp, who despite the divorce was still an intrinsic part of the company’s design team, had recently overseen two major technical missteps.

Vector was late in moving from machines with 8-bit processing to 16-bit, which had become the new industry standard. This left Vector—and its dealer network—selling a range of machines based on dated technology longer than other manufacturers. As a result, its customer base was slow to upgrade to new machines, choosing to wait until Vector released one based on 16-bit technology. This problem was compounded by the release of the Vector 3, its final 8-bit machine. The computer itself was as reliable as ever, but its keyboard wasn’t detachable and instead was built into the computer’s case. Users found this design uncomfortable to use and the Vector 3 became the first of the company’s machines to garner negative reviews.

Because of these mistakes, Vector failed to sufficiently expand its business before Big Blue arrived—even though Harp McGovern had correctly guessed that IBM was about to enter the game. Vector had little financial room to maneuver once the first IBM PC was released in August 1981.

Vector made another bad decision later that year, even after the impact of the IBM PC on the business microcomputer market became apparent: Vector continued to use the CP/M operating system rather than switch to Microsoft DOS.

CP/M had been the operating system of choice within the business sector for some time. Most business software was written to work with it, which made it the obvious choice for any microcomputer manufacturer around which to build their machine. Despite this, Vector had always enjoyed a close relationship with Microsoft, which had its own aspirations to be a power player in the operating system market. Indeed, Bill Gates occasionally worked out of Harp McGovern’s office when he was in town.

As a result, Harp McGovern had the opportunity to see, sooner than most other companies, what Microsoft was adding to its own operating system in an effort to capture the market. Once the IBM PC debuted with Microsoft DOS—not CP/M—installed, building future machines around this upstart operating system began to look more attractive. It could offer more functionality, while IBM’s adoption of DOS all but guaranteed that software companies would rewrite their business software to support it. It was a switch that Harp McGovern herself was inclined to make, so she contacted Gates and negotiated a provisional contract for Vector to pivot to using DOS instead of CP/M on far sweeter terms—and at a much faster pace—than were being offered to other manufacturers.

“We had an amazing relationship with Microsoft. I’d signed a contract where every update and every new system in perpetuity we would get at no increased royalty,“ she explained.

The deal was taken to the board, but the collective decision was made that it was better to stick with the known quantity that was CP/M for the in-development Vector 4. Switching would potentially mean redesigning the next line of machines. It meant re-educating their dealers and clients in the new operating system, and there was no guarantee that every piece of software they needed would be ported to it. The board, which included a number of ex-IBM employees, was also convinced that IBM would soon lose interest in the microcomputer market, leaving it entirely. If that happened, it would leave Vector alone on DOS—a precarious position to be in. In the end, the board agreed that moving to DOS was the bigger risk. This decision robbed Vector of the chance to be one of the first manufacturers to offer “IBM compatibility.” The window for survival in the post-IBM world would be narrow, and Vector had just narrowed it even further.

“I would say not having forced this through to make it happen was probably a flaw on my part,” Harp McGovern reflected. “By kind of going against my instinct that this needed to happen in order to be competitive. Because IBM was lusting after our dealer network.”

1982 was a tough year for Vector and the microcomputer industry in general. IBM aggressively pushed to gain market share with its PC, squeezing out many of the smaller players in this space. Harp McGovern worked hard, and successfully, to defend Vector’s share of the market in this hostile environment. Margins were squeezed, but the company’s commitment to quality and support gaveVector a fiercely loyal customer base and dealer network. Sales remained strong, and the company remained profitable. Vector seemed to have secured its niche. So at the end of 1982, Harp McGovern stepped back, relinquishing the role of CEO that she had held since founding the company in 1976. She oversaw the appointment of Fred Snow, an experienced industry hand from Honeywell, as Vector’s new CEO. Since the divorce from Bob, Harp McGovern had wanted to find more time to spend with her own children. She also wanted to fulfill the promise she had made herself as a child and travel the world in her spare time. Both Bob and Carole Ely had left the company by this point, and she decided it was her turn, too. She thought Vector no longer needed Lore Harp McGovern. She was wrong.

The final roll of the dice

In 1983, the Vector board petitioned Lore Harp McGovern to retake the position of CEO. In her absence, the company had lost more ground to IBM. Countering its moves required quick, decisive action, which the new CEO was unable to provide. The company’s market share had declined precipitously, and it was losing money at an alarming rate.

Harp McGovern was reluctant to step back into the fray.

“I had moved up to northern California at the time,” she said later in an interview. “I’d just moved up here a few months earlier with small children, nine and eleven, right after school was out, no friendship, no circle for them.”

Harp McGovern had promised to spend more time with her children. It was not a promise she was prepared to break. The board pleaded with her to return anyway, stressing that layoffs were already necessary. Without her back at the helm, they likely faced bankruptcy. Harp McGovern relented.

For almost nine months, Harp McGovern worked to save what was left of the business she and Ely had built. She oversaw a round of layoffs, which was painful for someone who believed the employees were the heart of the business. It was clear to everyone now that the future lay in IBM-compatible machines running DOS—the boat that Vector missed in 1982. Harp negotiated new investment to enable the development of IBM compatibility for the Vector 5 and beyond. . With gargantuan effort, Harp McGovern managed to drag Vector back close to profitability.

The personal toll, however, was enormous. Keeping the company alive took all of her talent, but it also took her away from her children. When she had agreed to become CEO again, it was conditioned on her not having to move back to LA. She wanted her now school-age children to have a stable home life. To achieve that, she endured multi-hour, long commutes to Vector’s headquarters in southern California.

“I commuted every day to Los Angeles between here and Burbank,” she said. “I would take a 6 a.m. flight. I’d get to Burbank, have my car in the parking lot, got to the office at 8:30. And at night, I’d try to get the 6 o’clock flight back so I could have dinner with my kids a little late but still have dinner, and the next day, do the same thing again.”

Soon, Harp McGovern wasn’t just fighting external battles. Friction grew with the board over where savings should be found. Where they wanted to find more cost efficiencies in staffing or production, she argued instead that they should seek new investment and expand into markets yet to be targeted by IBM. They rejected her plan to develop a new machine that would focus on networking and telecommunications, which she saw as the future of computing.

In the end, Harp McGovern was worn down. In 1984 she walked away (again) from her own company: “I finally said, ‘Guys, I’ve had it. I’m out of here.’ I dumped all my stock, had a good cry at my lawyer’s office because it was just…Oh, it was just…”

Life after Vector

Harp McGovern’s departure sealed the fate of Vector Graphic, although the company would limp on for a few more years. In October 1987 Vector Graphic finally declared bankruptcy. By that point, Harp McGovern herself had been out of the picture for three years. That didn’t stop a number of journalists from treating its failure as unspoken vindication that housewives—and Ice Maidens—lacked the mettle to succeed. The departure of Bob was often pushed as the turning point. Bob himself was often on hand to provide a useful quote in support of this idea.

“They didn’t develop any successful products after I left there,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1985 after Vector filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. “If the proper decisions had been made, it would be quite successful.”

By contrast, Harp McGovern refused to talk much about Vector for a long time after her departure. To her, Vector wasn’t just a company. It was more than that. It was something she and Ely had built from nothing into a profitable community of people.

Harp McGovern had only intended her absence from the business world to be temporary. By 1987, she was back. With Vector gone, she founded (and funded) one of the first companies attempting to develop disposable urinal funnels that would allow women to urinate standing up. Then, in partnership with her husband Pat, she launched a venture capital fund. In 1994, she became one of the original “Band of Angels”—one of the first angel investor groups in California focused on technology and life sciences.

“What I really enjoy is growing the company,” Harp McGovern said when asked what drove her. “Growing people within the company, accepting the challenge of being out there, competing against other companies and making an impact.”

At first, venture capital and angel investment seemed to offer those opportunities for growth, but over time she became disillusioned with this world. Many investors were happy to take her money, but they refused to accept that she might have useful advice to offer.

“After I’d done Vector—building a company from totally nothing to fairly good size with an international distribution network, having gone through raising venture capital, having gone through taking the company public and that sort of thing—I felt I could make a great contribution to other young companies that wanted to start in business,” she said later. The reality was quite different. Most entrepreneurs don’t want all the help I thought I could bring.”

Providing funding without hands-on advice held little interest for Harp. She eventually moved away from this industry as well.

In the end, Harp McGovern’s legacy would end up being something different. In 2000, alongside her husband Pat, she gave $350 million to endow the McGovern Institute at MIT. She played an active role in establishing it as one of the foremost research institutes into the brain in the world.

Of all the figures we have explored so far in this series, and of all those we are yet to explore, Lore Harp McGovern is likely the one who has been overlooked the most. Perhaps only Harp McGovern’s friend Sandy Kurtzig runs close. While Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak were building a computer empire in the suburbs of California, Lore Harp McGovern and Carole Ely were doing the same. As with Adam Osborne, however, the history of Silicon Valley likes to focus on its winners.

But the voices that are the most outspoken about the need for women to step up and beat men at their own game are often those that are the quietest when that actually happens. Harp McGovern didn’t just shatter Silicon Valley’s glass ceiling—the Ice Maiden (or “the awful bitch”) used its broken shards to carve out a place for herself, her company, and her employees along the way. All too often, her successes have been allocated to other people, while her failures have been attributed to her alone. For all these reasons, one of Silicon Valley’s true pioneers has been granted only a single inaccurate paragraph on Wikipedia.*

In 2016, Harp McGovern recorded an interview with the Computer History Museum. “I'm delighted to do this, mainly because there were so few women in the industry at the time,” she said, when thanked for her contribution to the museum’s archive. “And also for my grandchildren to see that their grandmother actually did things that not a lot of women did in those days.”

It’s not just Harp McGovern’s grandchildren who should be aware of her achievements. Because unlike many of those who kickstarted the golden age of computing, Lore Harp McGovern, in her late seventies, is still with us today.

If you are a young founder who finds themselves in her presence, you would do well to ask one of Silicon Valley’s last remaining original founders for her advice. If she’s prepared to offer it, then listen.

*As of April 10, 2024, Lore Harp McGovern's Wikipedia page is no longer a paragraph.

Gareth Edwards is a digital strategist, writer, and historian. He has worked for startups and corporations in both the UK and U.S. He is an avid collector of old computers, rare books and interviews, and abandoned cats. Follow him on X, Mastodon, and BlueSky.

To read more essays like this, subscribe to Every, and follow us on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.50.43_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Lore Harp McGovern—I’m delighted to know her name and her story. It seems to me her impact extends far beyond tech; the way she treated her employees and the demands she made and won on their behalf were incredibly progressive and maybe even more threatening to the status quo than her business savvy. What an inspiring human being! This is a truly remarkable story, beautifully told. Would love to see it on the big screen. Thank you, Gareth!

Brilliant to hear about a female founder for once!

wonderful story telling Gareth! And what a story. What an incredible woman.

What an amazing story! It is painful to see how she was treated and to what extent she was erased from the IT industry history books. Steve Jobs, Osborne, Wozniacki, all the usual (male) suspects but not this amazing woman (and these amazing women) who created the equivalent of a billion-dollar company as housewives. Also, so many lessons here on identifying market failures, filling them in as a to-to-market strategy, bootstrapping in action, partnering, etc. It feels like they were just completely-failed by the bro culture of SV. Happy to read that Microsoft was happy to deal with them, at least one white hat in a forest of black hats. Kudos for this very insightful history/story/business case!

Great story, one I never heard before. Thank you.

Minor quibble: I suspect the part about 8k versus 16k was meant to be about 8 bit versus 16 bit, a transition definitely underway at the time and related to the PC compatibility question as well.

@tommybgoode well spotted! Thanks for that. Fixed.

A compelling read, tribute, and heartfelt narrative 🙏💖👌📸