Get $60 Off Of Every

We just launched a new column on Every, and in celebration we’re giving readers 30% off of an Every subscription—a $60 savings—for a limited time. Subscribe before Monday, August 22nd and use this link to take advantage:

P.S. We ran this promo on Monday and the link was broken. Apologies for that! This one should work :)

The fundamental bet of a new business is that a founder can use the capital from investors to purchase a variety of assets, combine those assets in a unique way, and then extract more value than those assets could produce on their own.

Let’s say that I wanted to raise $350M for a crypto real estate company: I don’t really know how it will work, but I think stuff like ownership, community, and maybe even wave pools will be involved. Before any of that happens, I first need capital from investors. My investors hope that I will use this capital for building the business, but I may use it to fund my wife’s acting career. IDK. Regardless, the capital will be used to buy assets of some sort.

If you were to ask the average startup founder what got them excited about their new venture, not a single one would say “responsible stewardship of assets.” It’s all about building products! Building teams! Very few people get into entrepreneurship (or really anything worthwhile) for the joy of carefully managed spreadsheets.

However, the lack of interest in asset management never scales. The language of finance eventually comes for us all. Understanding how to communicate in assets allows technical leaders to relate with their leadership team; it means founders no longer glaze over when their accountant speaks; it means understanding investor’s incentives.

Knowing finance is power.

Perhaps the most fundamental atomic unit of business is the asset. Understanding what an asset is, why it matters, and why investors paradoxically like asset-light businesses is what we’re discussing today. This is the way I wish I was taught finance.

What is An Asset and Why Do They Matter

Asset is the kind of concept where the outline is clear but the details are blurry. Meaning that if you say “asset” in a meeting, everyone will nod their head in vigorous agreement while simultaneously thinking of entirely different definitions. While it would be easier if we could all just agree on something, the only realistic way for a savvy builder to navigate this dilemma is to understand what asset means in context.

On the outline level, an asset is any kind of resource with an economic value. That’s it! However, there is a huge difference between your boss calling you an asset and your accounting team deciding what number to put next to “assets” on the balance sheet.

Let’s take a step back and ask why we need to keep track of any of this stuff at all. The point of GAAP (generally accepted accounting practices) is to enforce some standard quantifiable version of a story that a business tells about itself, so that investors can look at the information the company puts out and have some reasonable trust that it corresponds to something specific in the real world. (Of course companies do everything they can to game this, and they often do so successfully, but that’s why the rules exist in the first place.)

If you're not learning, you're not doing your job. Get an Every subscription.

When you sign up for a paid subscription to Every you'll get access to:

- Every article we publish advertisement free

- Our back catalog of hundreds of essays, explainers, and interviews

- Our Discord community where you can interact directly with our writers

Every article we publish is designed to help you level up in your business and in your life. Take advantage now because we’re giving readers 30% off of an Every subscription—a $60 savings—for a limited time. Subscribe before Monday, August 22nd and use this link to take advantage:

So if standard transparent information for owners (or potential owners) is the reason for accounting classifications generally, what is the need for the idea of an “asset” specifically? It’s to give you some idea of what a company could be sold for if it needed to be shut down.

In business, assets break down into 4 broad categories. They are:

Current Assets

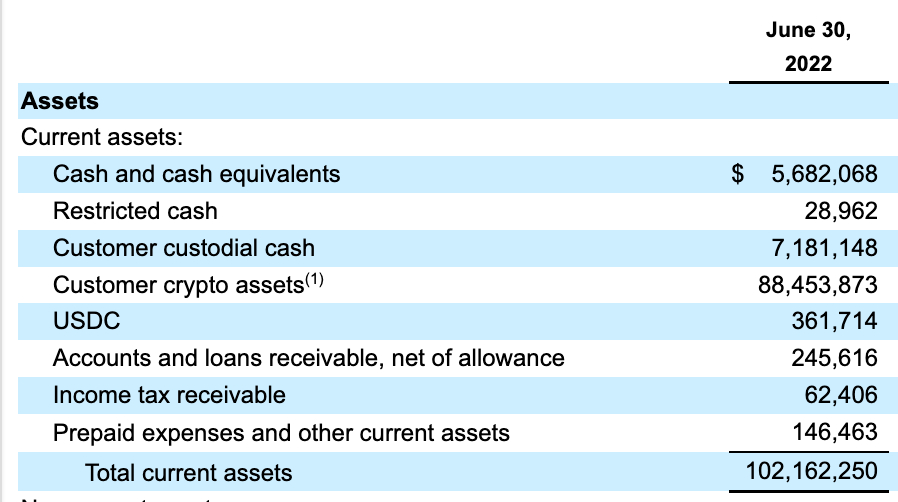

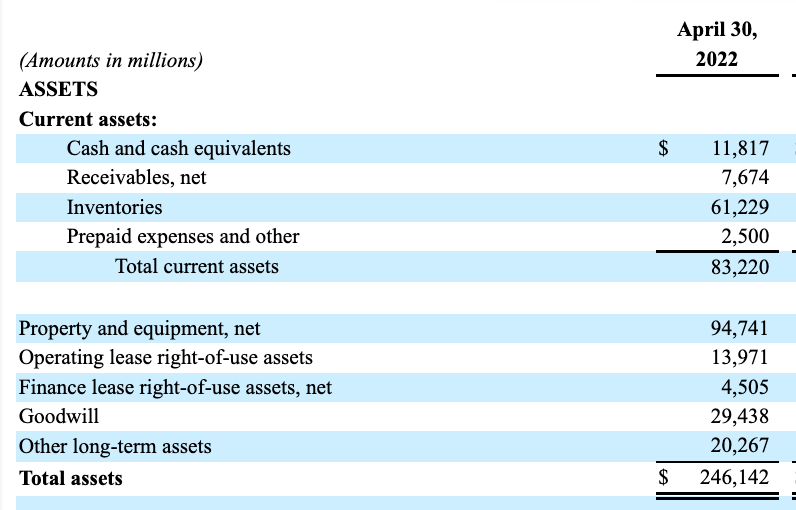

This is the easy to liquidate, one-step removed from cash assets. Sometimes called short term assets, they are what a company uses when it needs cash quickly. When ish hits the fan, you’ll want to have current assets readily available. Interestingly, there is no universal rule on what level of disclosure is required, so you’ll often see different companies emphasize different things depending on their type of business. Let’s take a look at two examples:

The first is Coinbase and the second is Walmart. You’ll note that despite both being public companies, and both being held to the same rules by the US government, they look vastly different. Coinbase has all this crypto mumbo jumbo and Walmart, in both their documentation and earnings calls, focuses a ton on inventory. These are strategic choices by the companies to act as signaling mechanisms to the market.

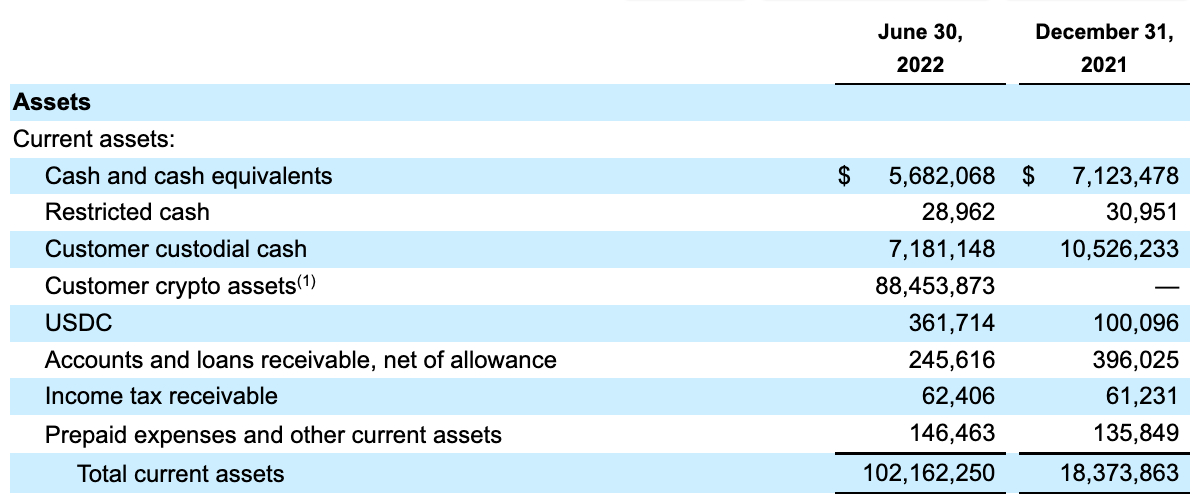

However, there is an even more interesting story if you look at the two year view of Coinbase’s balance sheet.

The line “Customer crypto assets” is a totally new thing that the company didn’t account for before. The security exchange commission (SEC) required the company to disclose this and it suddenly appeared. This caused all hell to break loose. On Twitter, people with cartoons for profile pictures howled for blood arguing that if the company went bankrupt, customers’ assets would be seized. It was such a big deal that the company had to write a blog post saying that this rumor wasn’t true.

Why does this matter? It’s the perfect example of a point we will return to again and again, finance is not a science, it is a story. The metrics housed within any public filing are narrative as much as they are number, and any party with power over the documentation will push and shove the narrative as they see fit. The SEC is increasingly coming down on crypto and scrutinizing the sector, as such, they have issued a variety of rulings against Coinbase. The company’s current assets are just a good example this point.

However, the world is not all digital assets, it's stuff that is actually useful too. The second thing an asset can be is…

Fixed assets

For the assets that last longer than a year, they will be given the title of fixed assets in textbooks. In most meetings, you will typically hear it called “PP&E”: property, plants, and equipment. Here again there is more financial tomfoolery, specifically in how you depreciate the expense. Depending on which country a company is headquartered in and what accounting standard they adhere to, depreciation can occur over the “useful life” of the asset or on a more accelerated timeline.

Look, this isn’t an accounting newsletter (thank you Lord for that) so I’m not going to go into more detail than what we’ve already done. The important thing is that it is insanely nuanced and insanely opaque. No public company talks about how they do this, and it isn’t information that is readily available. However, it does make a big difference—how you treat your assets, how you claim depreciation expenses can result in huge swings in valuations.

One of the best trades I’ve ever seen was a hedge fund manager who posted a $XXXM profit on a stock short. He realized in discussions with a public company’s investor relations team that they were doing their depreciation scheduling incorrectly and that the truth would come out in 7 months after an audit. 8 months later and he was sitting on a cool $100M+. Understanding accounting is a great way to make money.

Fixed assets get a lot trickier with digital goods like software, but they can fall under that banner. More on this in a sec.

Almost done with the four categories! Don’t give up on this piece yet!

Financial investments

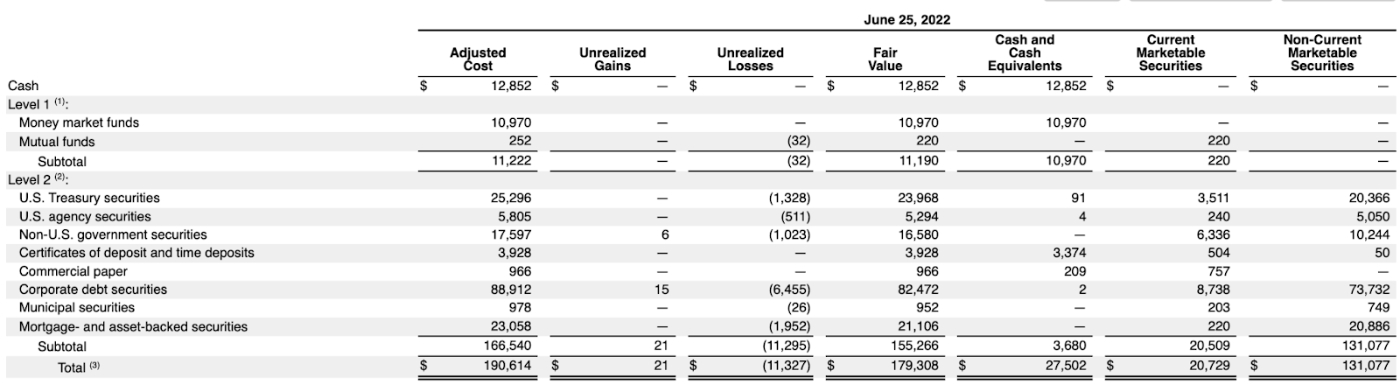

Say you are an uber successful company like Apple (not Uber). One of the best parts about being a great company is that you get to make lots of cash. A company can, and probably should, return it to shareholders, but sometimes they choose to keep it. But when inflation strikes, you don’t want all of that sitting in a bank account. You want it out in the market, hopefully making a return, or at least keeping up with inflation. This is where you’ll see some companies engage in a little bit of hedge fund tomfoolery. They will deploy their excess cash in a huge variety of options. For a sense of how complex this is, look at this chart from Apple’s Q3 2022 filing. This is just what they are doing with their excess cash!

While at first glance, this feels like an excessive amount of detail, but when you consider that this is all the info investors are given on how ~$189B is being deployed, it starts to feel paltry. This sort of activity has led to Wall Street Journal headlines like “Apple is a hedge fund that makes iPhones.” If you wander the halls of any major public corporation, somewhere deep in the bowels of the beast, you’ll find a string of desks, gleaming with Bloomberg terminals, drenched with hair gel and Doordash receipts and Patrick Bateman posters. Which is to say, every major company has their own internal trading team, with some 2012 research pegging $1.6 TRILLION in assets being shadow managed by corporations. To make it ickier, because it happens within companies, no disclosure is required regarding the kind of investing activity they are engaging in.

Truthfully, none of that was required for you to truly understand what an asset is, but I figure this is the sort of stuff that makes you sound smart at cocktail parties, and y’all love that sort of thing.

Intangible assets

Alrighty! Last type of thing an asset can be is intangible. Intangible assets are the best example to highlight the difference between accounting and finance. While the professions are as closely related as newlyweds in West Virginia, they are not the same thing. Finance is about long-term power: it deals with the strategic use and investment of capital. Accounting is tracking the day-to-day flows of value. Accounting is concerned with painting a hyper-accurate current picture of reality. Finance is less fussed about all of that.

In most cases, that would be totally fine! However, for intangible assets, it means there is often strong disagreement between the two functions. When trying to value a brand or a patent, accountants have to use the principle of conservatism. Essentially this means that because we don’t know the value of something, we should ignore it until a clear value can be ascribed.

This is particularly important because most technology companies' competitive advantages are arguably intangible assets. Ask yourself this: what value would you ascribe to the network effects of LinkedIn? How valuable is the data housed therein? When Microsoft bought them from $26.2B in 2016, the company had a book value of assets worth roughly $7B. The $19.2B difference comprised future expectations of cash flows AND the other assets that up to the point of acquisition hadn’t been valued.

Confusingly, software, despite literally being an intangible asset, is typically thrown under the banner of PP&E! Depending on payment method, the percentage of the software developed in-house, and the manner in which the software is used, it can be considered an expense or an asset. What a mess.

Note: This is a newsletter, not an accounting agency, so I will not summarize the hundreds of pages of documentation required to understand the nitty gritty of this stuff.

However, the difference between finance and accounting is minute compared to the difference between executives and accounting. Perhaps the most crucial assets of all, a talented workforce and productive culture aren’t even considered assets by accountants! They’re an expense! There is a vast difference between how financial statements portray the world and the reality outside of them.

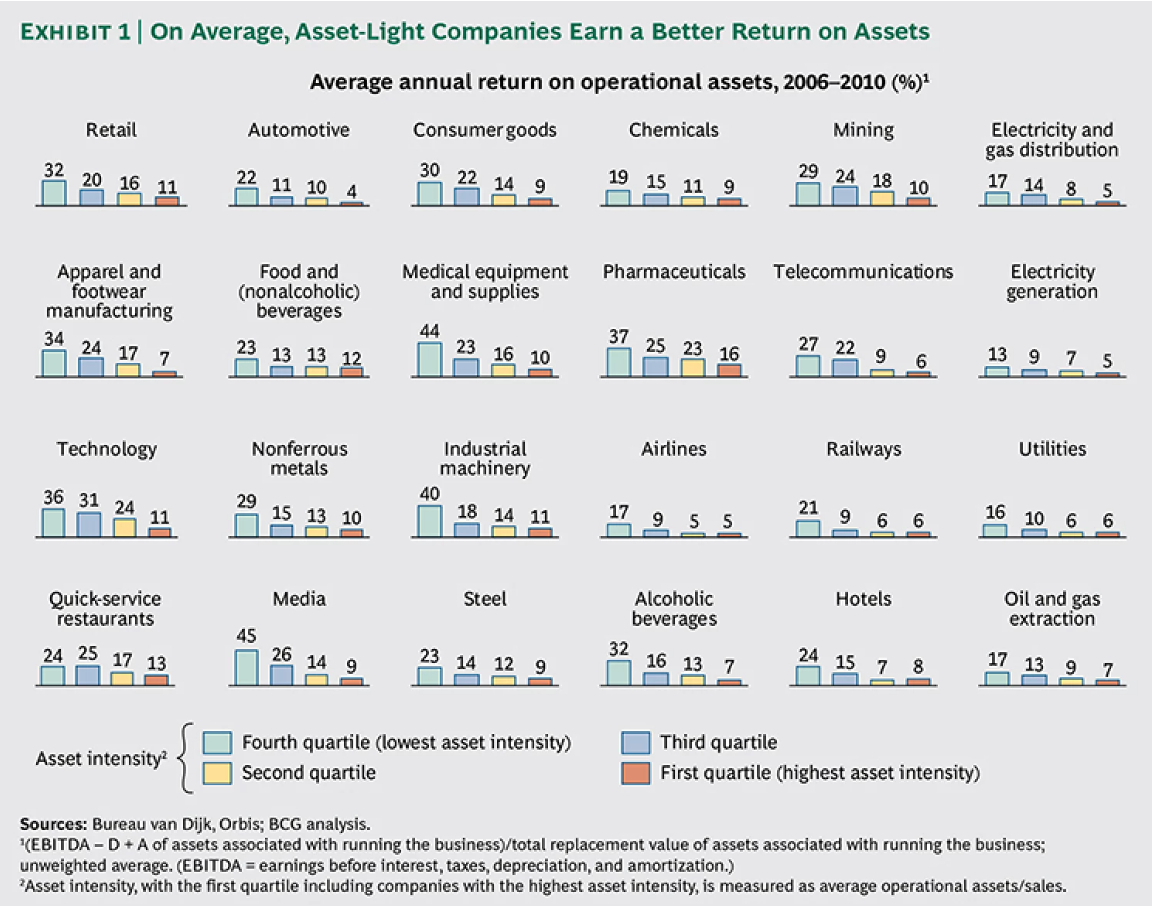

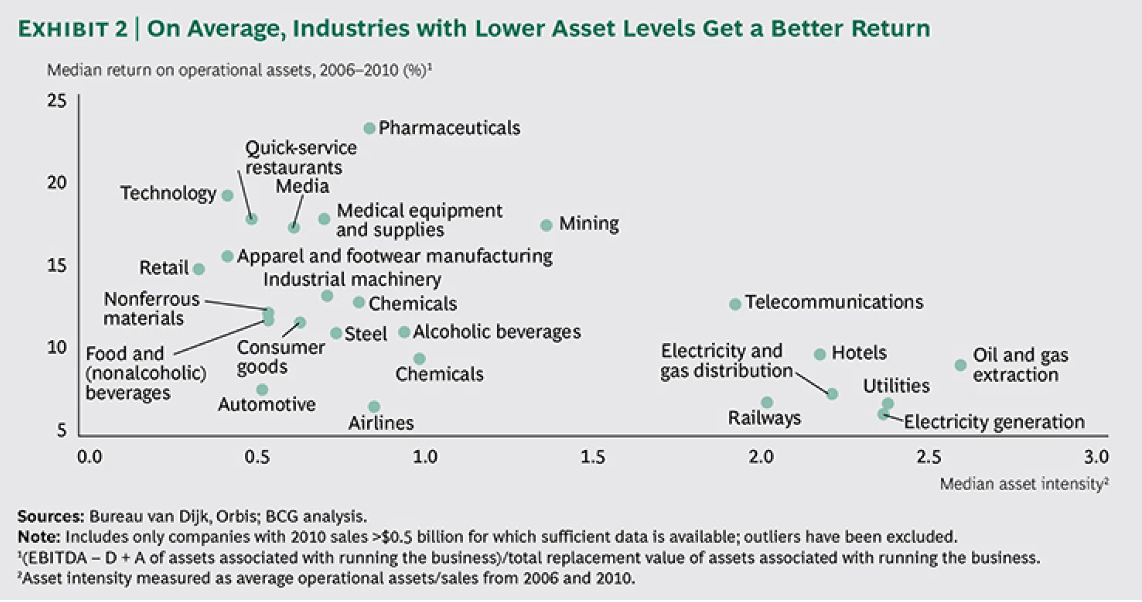

How To Think About Technology Companies in the Pursuit of Assets

Perhaps most counterintuitively of all, the most successful companies have as few assets as possible. Rather, they are able to wring more economic value out of the minimal amount of assets. Those companies who utilize an “asset-light” model consistently outperform their asset-heavy peers. The more assets that are required to make your economic engine work, the more capital you must raise and the lower the return on invested capital. Said another way: which business is better, the one that requires $5M to hit $100M in ARR or the one that requires $200M to do the same $100M? The second business will have higher costs, will be less flexible, and may have a harder time convincing employees to join. The data backs up the logic too. The next two charts are from a study that BCG did of 2,687 companies across 24 sectors. Asset-light companies have a better return on assets.

And industries that require fewer assets, on average, perform better.

There are notable exceptions, with some of the most highly valued companies today (Walmart and Tesla) taking an asset-heavy approach, but they are the exception. Total vertical integration is a risky strategy.

Really it’s pretty simple. The more a company can offload its unprofitable assets onto suppliers, the better return they can generate.

An investment round into a project is about purchasing a returns driving asset. Sometimes asset means the accountant definition, sometimes the CEO one. The game of finance is knowing when and how you should appeal to the right audience.

A New Course From Napkin Math

This post is already super long and there is so much detail that we didn’t have time for. Theory is all well and good, but how do you apply this? How do you use the theory I just gave you to get projects approved or investors to put capital into your startup?

This problem is especially acute for founders and builders. Translating the language of building to financial statements is key if you want to succeed in your career, but is near impossible to learn on your own.

If this sounds like a problem you have, I want to help.

I’ll be running a new workshop with a group of 30 builders that will kick off at the start of October. We’ll do a ~5 week sprint, using each week to thoroughly cover key financial terms: how the term works, how it is evaluated, and how you can use it to your advantage by getting capital. The goal is that you will walk away able to quickly evaluate your own (or others’) businesses and know how to communicate the value of your work to those who are non-technical. Think of stuff like defining ARR, what revenue is, and the CAC/LTV ratio.

I’m limiting it to 30 seats because I want to make sure everyone can participate fully. I’ll be teaching the class myself and will customize the curriculum based on everyone’s needs.

Next week I’ll email out more information (curriculum, guest speakers, pricing, etc.). If you want to get that email, you can sign up by clicking the button below. Divinations (another newsletter in the bundle) did a course and sold out really quickly, so if you are interested act fast!

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!