If you would prefer to listen to this essay, you can do so on Spotify. My uniquely grating voice pairs perfectly with a morning commute. —Evan

Last weekend, a crowd of revelers in San Francisco’s Chinatown burned an autonomous vehicle from Waymo down to its frame.

Source: XLet’s ignore that this is, like, a crime. And let’s also ignore that destroying cars is a proud American tradition—one practiced by my fellow Bostonians, whether our teams win or lose.

What I would like to call attention to is the misunderstanding that this event begat. Some in tech struggled to empathize with why people were upset. In the opposing corner, on Twitter and in private conversations with me, others expressed a gleeful sentiment about the car’s destruction, with some people unable to grok the humanity-advancing technology these cars represent.

This single incident of arson is a broader signal for what has gone wrong with how the technology industry manages its public perception in America.

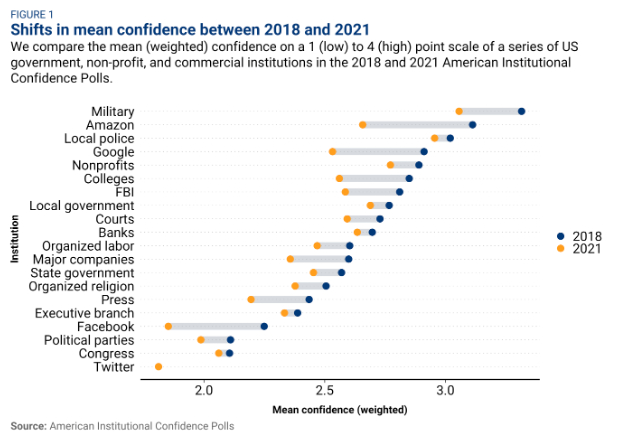

During the boom years of the 2010s, when Facebook was uniting the world during events like the Arab Spring and people were generally optimistic that the new internet companies would make the world better, polling indicated that the average American loved tech. People had more confidence in Amazon than the press, college, non-profits, the FBI, or organized religion. The popular media embraced nearly everything we did under a halo of goodwill and good faith.

Starting with Donald Trump’s election and shifting dramatically during the pandemic, the general public started to turn against the tech industry.

Source: Brookings.Tech is now the fifth least-trusted industry in the United States, only narrowly edged out by banks and healthcare insurance. It is a bad sign when the industry responsible for the majority of the U.S.’s GDP growth is in the same sentence as the companies running our mortgages. People not only distrust tech, they actively dislike it and see it as harmful.

The industry of the future has lost the trust of the present, for reasons that are hard to pin down. Maybe it was the fraud perpetrated by Theranos, the concerns about Facebook’s role in the 2016 election, the misinformation on Twitter during Covid, the stupidity of WeWork’s existence, or the monopolistic practices of Apple, Google, and Amazon. When referring to something as nebulous as “confidence” in a country as diverse as America, there will be no singular cause for its downward slide.

And really, it doesn’t matter whether you believe that shift was wrought by our own hubris or by the mainstream media writing unfair hit pieces; what matters is that this is reality. This is a problem.

It means that many startups have to justify their existence not by explaining why they’ll make the world better, but by actively showing they won’t make the world worse. Take, for example, the Browser Company, which recently released a new take on web browsing with AI. The product uses AI to compile information from a bunch of websites into one location for you, automating away the need to click around to different sites.

Almost instantly, the issue raised wasn’t how this was better than the status quo, but how “there’s reason to worry.” While it’s important to consider how AI will change the economics of online content production, it’s premature to put all that concern on a small startup—and it certainly wasn’t a question that the company would’ve had to deal with years ago.

Negative consumer sentiment becomes a compounding entropy feedback loop, feeding dumb regulation, gotcha headlines, and resentment. And from a purely capitalist perspective, it makes it harder for these companies to grow.

Transportation in Silicon Valley is the perfect case study on how the tech industry has gone awry.

Autonomous competition

There is an old maxim: If you want to see what new tech companies will be formed, just look at what problems are annoying Palo Alto residents. Can’t find a dog walker? Try Rover. Don’t have time to cook? Doordash. You get the idea.

In 2009, the overwhelming problem was commuting. The Bay Area has that special type of urban design where it is neither walkable nor drivable. Sprinkle in an absence of bike lanes and an abysmal public transportation system, and you have a recipe for startups. Uber spawned out of this hilly hellscape, allowing anyone to call a ride at the click of a button. Around the same time, Google (now Alphabet) started to work on its self-driving car division, Waymo, which was publicly announced in 2010. Its pitch was simultaneously blase and grandiose, that uniquely corporate brand of communication that says interesting things in a way that makes your eyes bleed from boredom. In a blog post, the company pitched the benefits of its product:

“According to the World Health Organization, more than 1.2 million lives are lost every year in road traffic accidents. We believe our technology has the potential to cut that number, perhaps by as much as half. We’re also confident that self-driving cars will transform car sharing, significantly reducing car usage, as well as help create the new ‘highway trains of tomorrow.’ These highway trains should cut energy consumption while also increasing the number of people that can be transported on our major roads. In terms of time efficiency, the U.S. Department of Transportation estimates that people spend on average 52 minutes each working day commuting. Imagine being able to spend that time more productively.”

You can already see the seeds of its destruction: Rather than pitching a future straight out of science fiction, where we are free of driving, Google instead makes the coup de grâce of the pitch about having 52 more minutes to work. Yay? To be fair to Google, that pitch would’ve landed in 2010, as good will toward tech was high at that point.

Over the next few years, car companies continued to work on driver-assist systems, like more advanced versions of cruise control, but otherwise, the sector was relatively quiet. Then in 2014, Google fired the starting gun by announcing that it had made a super-cute custom vehicle called the Firefly.

Source: Google.This adorable little thing got everyone going. Tesla announced its “Autopilot”—a marketing term for an advanced cruise control system—soon after. Musk strode up and down stages over the next few years, slinging promises and catchy phrases, selling an autonomous-vehicle future to his fans. It was always just a year or so away (dear reader, it was not). Cruise, another startup attempting to build autonomous vehicles, was acquired for hundreds of millions of dollars by GM in 2016. There were dozens of companies working on this technology. I remember talking with founders around that time who told me that autonomy “will be completely solved by 2020.” (Whoops.)

This was the energy in the air. Tech hadn’t yet had its collapse in public perception. The vibe of that initial Google blog post, the casual spirit that “Of course we will save the world!” was injected into every product Silicon Valley built. The tech-is-default-good bubble had yet to pop.

Gradually, everything went wrong. More and more drag entered into the system, starting with the obvious—most companies could build a flashy demo, but couldn’t build a usable product that covered all the edge cases. The technology turned out to be much more challenging than people were willing to publicly discuss. To keep investor sentiment high, Tesla relied on sex appeal, selling “Full-Self Driving” packages to consumers in 2016—four years before the technology was ready to start public beta-testing (yikes). Other competitors tried to differentiate on where they deployed their tech—one, for example, bragged that retirement communities were perfect testing grounds for its vehicles. Everyone was aggressively fighting for the future and, in so doing, overpromising what they could deliver and under-discussing the tradeoffs.

Then in 2018, the inevitable happened: A test vehicle from Uber killed a pedestrian in Arizona. By 2019, 29 U.S. states had rolled out regulation related to autonomous vehicles, with some form of testing and permitting process required for all of them. In 2023, a Cruise vehicle ran over a pedestrian in an accident and maybe, sorta, covered it up? The details are still unclear.

By early 2024, the autonomous car landscape looked like this:

- Tesla is marketing full-self driving while not actually being able to deliver on that technology. What they have today amounts to a very good cruise control plus a few extras.

- Waymo has live demos with vehicles in a few cities and is slowly rolling out elsewhere. This reticence is despite a recent independent study from Swiss Re (a large insurance company) establishing that Waymo has “100% fewer bodily injury claims and 76% fewer property damage claims…[it] is significantly safer than human-driven vehicles.”

- Cruise has been gutted with 24 percent of its staff laid off and nine executives fired. It hired a chief safety officer this week.

- Uber paused its self-driving program after the 2018 accident, eventually selling the technology to a competitor in 2020.

This state of affairs has led to widespread public distrust and the incident of arson over the weekend.

It is a fact that self-driving technology can dramatically reduce human suffering. The vehicle industry is one of the most expensive and dangerous we tolerate. In 2021 there were 5.4 million injuries from cars. These accidents cost $498 billion. Most tragically, 46,890 people died in motor-vehicle deaths. That is 20,000 more than have been killed so far in the current Israel/Gaza conflict and about 2,000 fewer deaths than what we lose from gun-related violence in the U.S. None of these are apples-to-apples comparisons, but they give you a sense of the scale of suffering. It is an invisible, pernicious loss of life that society has accepted. So why are we trying to be cute about it?

Waymo has mostly solved the problems of vehicular injury. If someone emerged with a fool-proof technology to stop shootings in America, they would be given the Nobel Prize. It would be an earth-shattering achievement. In the case of vehicular manslaughter, these companies have fumbled the public perception so strongly that we got arson.

Many tech companies have learned the wrong lesson from the tech backlash. We should still be selling the future and our capability to deliver on it. An honest reckoning of the future also involves an honest reckoning with the risks involved. We should no longer be reliant on the gilded idealism that the American public had before 2016; instead, we need a candid, real discussion among companies that confront the tradeoffs of their technology—and argue why it is worth it.

Waymo and Cruise should publish a blog post titled “When We Kill Someone,” in which they discuss how a fatal accident is an inevitability, but the tradeoffs of progress are worth it. Risk should be discussed and embraced. The world needs neither luddites nor accelerationists, but an intellectually honest discussion. Our industry has put ourselves into a corner where this is the only option left.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Well, son, a lot has changed since 2010. Quintupling your net worth (in some cases) at the expense of US might have something to do with it. For one, I don't think the criminati denizens of the Barbary Coast even gave a rat's patoot whether the vehicle was autonomous or not. If you asked 20 synapse-less San Frannies to use WayMo in a sentence, you'd be giving them "way-mo" credit than they deserve. Hell, they probably couldn't spell "autonomous" if you spotted them the "autonomous." What probably happened was a vehicle was moseying by with no one on board. In today's post-accountability world, that was good enough to immolate the eff out of it. I wouldn't give the crowd any more credit than that.

It seems odd to frame this around the idea that it’s some kind of inconvenience that people no longer blindly accept that tech companies are working for the betterment of society, because they have proven that in many instances, they aren’t. Research has even shown that the idea that FB was a critical, positive tool during the Arab Spring was a false perception. The tech industry was given the benefit of the doubt, and having shown that they don’t deserve it, people are asking questions. Jon Stewart said it best in his recent return to The Daily Show: it is not the public’s job to stop having concerns and asking questions, it is the job of the people asking for the public’s support to assuage those fears and answer those questions. Bemoaning that lack of public goodwill towards tech seems like a strange position to hold.

@pn Good feedback! I would argue that companies should front run those questions and clearly discuss the risk, while strenuously making the case for the future. You could believe (and I would probably agree with you) that tech companies shouldn't of had such a hall pass in the 2010s, however, in the backlash we've gone too negative while companies have simultaneously not updated their corporate comms.