My post last week started with a bold claim: Today, Californians can call an Uber. Tomorrow, they can’t. Lyft had announced that it would shut down and there were signs showing that Uber was going to as well. However, if you live in California and open your Uber app today, you can prove that this didn’t happen.

In this post I’m going to explain why they didn’t close and address a few follow ups from readers: what do drivers think of AB 5? How did it get written in the first place? What are the differences in pricing between Uber, Lyft and taxis, and how would reclassification change the competitive dynamics? Let’s get into it.

What happened?

After I published the piece, an appellate court granted Uber and Lyft a temporary reprieve which delayed the order that would’ve forced the companies to reclassify their workers as employees. The reprieve didn’t resolve the issue. It simply granted Uber and Lyft more time.

In a way, this is worse for Uber and Lyft. Previously, they would’ve shut down their services for a few months until voters could decide what the policy should be. While less people are using rideshare (Uber mobility’s Q2 2020 top line is about 1/15th the size of what it was in Q4 2019), it still would’ve reminded riders of the value Uber provides. Even if a rider had just one frustrating experience — failing to be able to get across town, for example — it could have pushed the ballot in Uber’s direction.

But now that Uber and Lyft can remain open, what will voters decide? We’ll have to see in November.

What do drivers think?

One request I heard from a couple readers was to analyze what the drivers thought about the bill.

The RideShare Guy, a popular blog for ridesharing drivers, has performed several surveys asking everything from which platform drivers use to which model of car they own. Particularly for our interest, they’ve done surveys on the independent contractor vs employee debate.

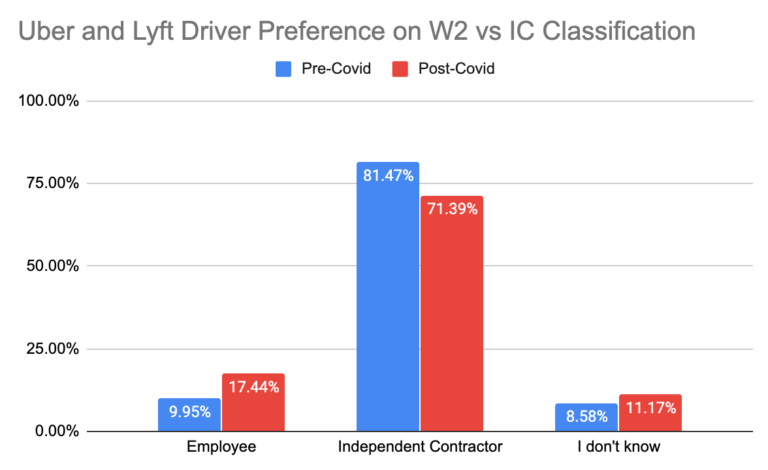

A survey in May 2020 found that a significant amount of Uber drivers prefer being independent contractors. The percentage has dropped from 81% to 71% since Covid-19 began, but contracting still represents a significant majority.

(Source. Note: survey received 734 responses.)

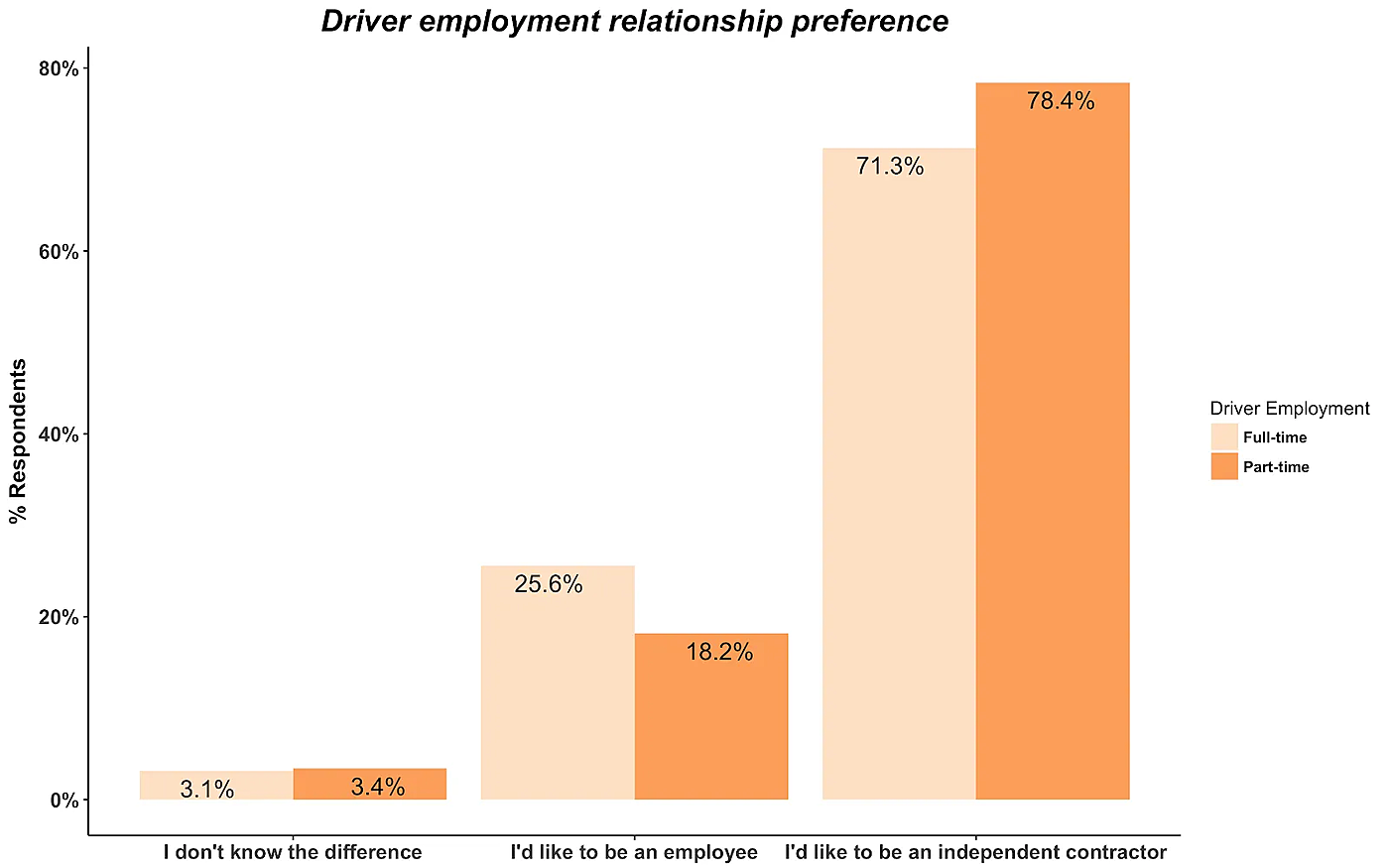

To steelman this argument, one might argue that the number of rideshare drivers isn’t the right n. Instead, it should be weighted by hours driven. Uber drivers that work 40 hours a week are in a much different position than those that work 15 hours a week. One would think the workers that work full-time as a driver would be more interested in the benefits of employment (health insurance, paid time off, overtime compensation, etc.).

In 2018, The RideShare Guy did a survey that delineated between part-time and full-time workers and their desire to be employees. Turns out that while full-time workers had a slightly higher preference to be employees, a strong majority wanted to stay as contractors.

(Source. Note: survey received “nearly 1,200” responses.)

Finally, there was a study published just this week that interviewed 1,002 app-based drivers. 89% of drivers showed support for Uber’s new independent contractor plan, which began a discussion about how Uber might provide benefits but still allowed for independent contractor status.

Granted, for this survey the sell was pretty easy. Drivers were shown the following statement and asked if they agreed:

This plan would combine the flexibility of Independent Contractor status with some benefits and protections typically associated with being an employee. This plan would not make Drivers employees, and therefore they would not be entitled to all the benefits and protections of employment, but they would receive more benefits than they currently receive as an independent contractor.

Sometimes it’s easy to forget the unique value proposition that these ridesharing companies provide to drivers. Driving for Uber or Lyft is the only job in the world where workers can make a living wage with the amount of flexibility they provide. A Medium post by Alison Stein, an Economist at Uber, summed it up well:

Think about it this way: Starbucks offers one of the most flexible part-time jobs around, but baristas can’t just walk in unannounced, decide they will only make lattes while refusing all orders for cappuccinos, leave during the morning rush to go pick up their kid from school (without permission from their boss), and return to work at a Peet’s Coffee. That would absolutely be allowed under the law, so why doesn’t it happen?

Why Was AB 5 Written?

So if most surveys show that drivers want to be independent contractors, how did AB 5 even get written? There are a few explanations.

The first one is that these surveys don’t accurately reflect the sentiment of drivers. The minority who wants to become employees lack really valuable benefits: employer sponsored healthcare, unemployment insurance, etc. These people need to be taken care of and classifying drivers as employees improves the lives of many.

The second reason this may have been written is because of lobbying dollars. Lorena Gonzalez (a politician serving in the California State Assembly) was the one who wrote the bill. She has been public about the fact that the Teamsters (one of the country's largest unions) supports her. Could this be a way to please the leadership of the unions in order to continue the funds flowing? Perhaps.

Finally, another good argument in favor of AB 5 is that Uber and Lyft never have been lawful when it comes to drivers. As mentioned in my article last week, employees cost 1.25x to 1.50x more than contractors. Around 80% of Uber’s Gross Bookings go to drivers. If they don’t pay them properly, this could be considered a transfer of wealth from Uber drivers to Uber leadership and investors. Not a great trade.

Price Differences Between Uber, Lyft and Taxis

Previously I made the case that, in the hypothetical world of increased labor costs, Uber would have to raise prices if they wanted to remain profitable. These prices raises would decrease ride volume as riders looked to other options to compensate (taxis, public transit, walking, etc.). But just how much cheaper are Uber rides?

RideGuru, a ride price comparison site, performed an analysis between Uber rides, Lyft rides, and taxi rides. Which of these was cheapest? To answer their question, they compared the three options against a 4-mile ride.

Out of the 20 cities RideGuru looked at, taxis were the most expensive in every case except New York City (where Uber was the highest). For the other cities, Uber and Lyft averaged 5% to 50% cheaper.

Outside of the “average” ride, there are a few divergences in prices. During busy times Uber and Lyft use surge pricing — making their rides more expensive than taxis. Additionally, during longer trips (above $35) Uber and Lyft are cheaper than taxi rides.

From this data, it seems that a bump in Uber and Lyft prices would bring it a lot closer to taxi prices, although there will still be certain cases where Uber and Lyft are cheaper. As we think about customer behavior, we also have to consider the non-monetary benefits of using a ridesharing service: increased security, calling on-demand, and better technology (payments, etc.).

It’s unclear how much Uber and Lyft would raise prices if they had to pay employee benefits. But there’s no doubt that it would affect consumer demand.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.08.31_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!