In Partnership with Product Growth

Product Growth is a once-a-week insightful newsletter that covers the latest technology, product management, and growth topics.

Hendrix had his Fender Stratocaster. Yo-Yo Ma, his Stradivarius. Steve, your lovable dumbass neighbor from college? He has Tinder. The match of his bronzer-lotioned finger with Tinder’s devilishly swipeable surface is the ultimate pairing of tool and tool. It is a symbiotic relationship—in exchange for dollars, Tinder provides, as Steve so colloquially calls it, “babes.”

However, Steve has a secret: a deep, all-consuming love for the opera. In his pursuit of the perfect babe, Steve is looking for someone who will share his affinity for crying to Pavarotti and crushing White Claws. Normally, he might have issues finding such an individual at Rush Week. But with Tinder’s AI algorithms, the alto alcoholic of his dreams is just one finger flick away.

So why does Tinder matter? Because it facilitates love and, by extension, grows the world’s population.

Many technologists look to work at a mission-driven company, to make a difference in the world. To do so, they duct-tape together bits and atoms into a shape that produces net new economic activity. When you look to change the world, you may think of frontier sciences: nuclear fusion or space flight or large language models. I do not deny that these things are objectively cool. However, I would argue there is someone with a greater, more immediate need for help from our most brilliant minds. That person is Steve.

I will also admit to having once been in a similar situation as our operatic frat bro. In 2020, my love life was a disaster, and I couldn’t find anyone I really clicked with. Then, one day on Hinge (a dating app owned by the same parent company as Tinder), I got a “most compatible” recommendation from their AI algorithm, and there on my screen was Morgan. We had no mutual friends, no overlap in our interests, and to the casual observer, nothing in common. She is an academic who studies English literature, and I, well, I am a nerd who likes startups.

But somehow, Hinge’s algorithm knew we would get along. Our first date went for 3x as long as we planned. Our second date was supposed to be an hour and ended up being six. A little over a year after meeting, we were married. The best thing that ever happened to me was only possible because of a recommendation algorithm. An underappreciated fact about dating apps is that they pierce social circles. You meet people you never would've met normally, and I just happened to meet my soulmate.

Love lifts us up where we belong…is the purpose for living…all that Hallmark-branded hullabaloo. Theoretically, I could end my argument right here. But this column is Napkin Math, and so we have to talk about the real reason love matters: It makes the economy work. And the reason why is simple.

We need more babies.

The economic importance of finding love

I cannot overstate how critical it is to have a young labor force.

Almost all Nobel Prizes were awarded to researchers who discovered their results between the ages of 31–40 (41.8% and 47.4%, correspondingly). Young people make pension insurance programs like Social Security possible by paying into the deposit base. Old people take a ton of federal resources—the U.S. government currently spends 40% of its budget on people 65 and up. Young people are a malleable workforce that can be funneled toward where opportunity is.

When a country goes below population-replacement levels, there are ever more elderly supported by ever fewer young people. Countries like Italy and Japan have already seen flagging economies from lower birth rates. Rural towns slowly die as young populations consolidate around urban centers. To try to prevent similar problems, Korea has spent over $150B to encourage families to have more kids. Importantly, this spending has made no material difference.

Theoretically you could fix these concerns caused by shrinking populations by:

- Enabling the elderly to work for longer and be healthier for more years

- Decreasing the level of government support to the elderly

However, option one feels very distant, and option two feels deeply cruel. The best remaining option is probably to make more babies. This is even with factoring in the environmental concerns that increased populations bring. We have to make the bet that technology like fusion or fertilizer will allow us to keep up with the power and food requirements of a growing planet.

America is screwed until we figure out how to screw again.

Where is the problem?

In case you were unaware, we have a real problem: Fertility has rapidly decreased in the Western world. In the U.S., the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) was 2.2 births per woman in 2008 and was 1.7 per woman in 2019. This dip below population-replacement levels means that, when coupled with America’s collapsing immigration rates, America’s population will begin to decrease. This is bad for reasons we will discuss in a sec.

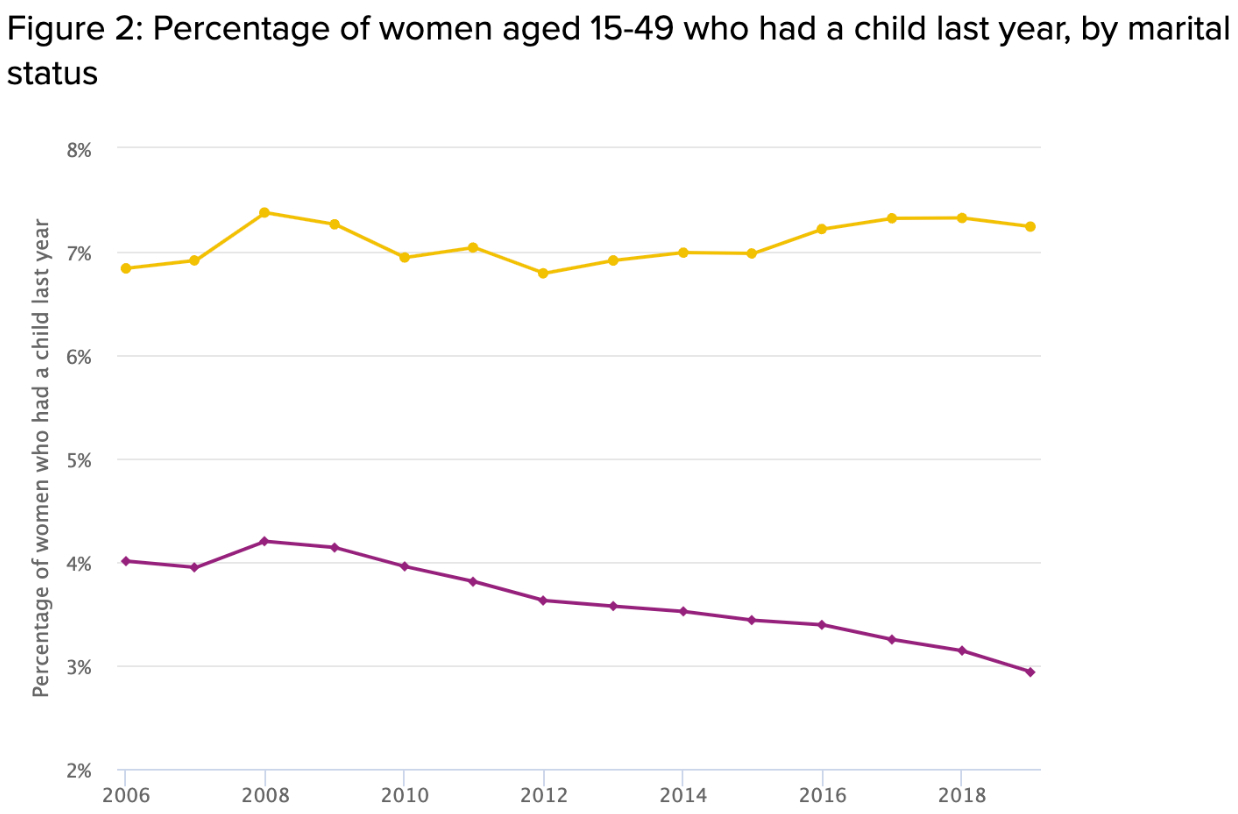

With closer examination of the TFR stats, something really fascinating emerges: Fertility rates in total are going down, but not among married women. If you’re married, you’re having the same number of babies as before (yellow line in the graph below). Fertility rates are going down, but the fertility rates of married people are pretty much the same. (Purple is fertility rates among single women).

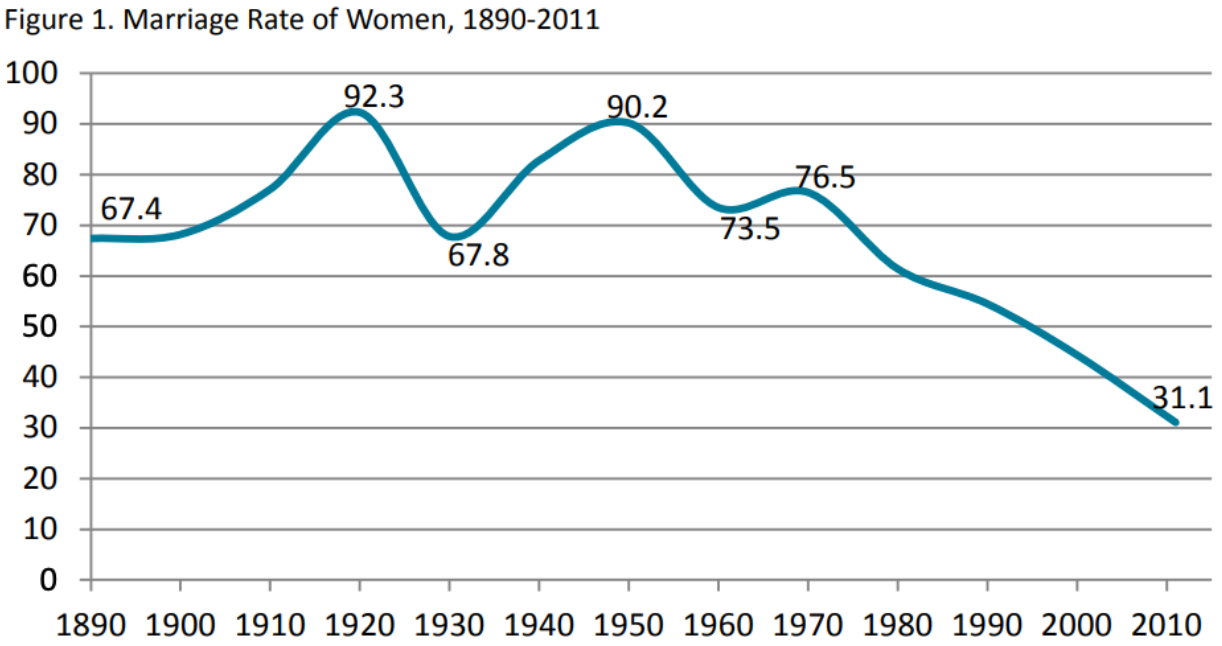

As you’ve probably guessed, the real problem is in marriage rates. These have fallen by 70% since 1970. “The U.S. marriage rate (the number of women’s marriages per 1,000 unmarried women 15 years and older) is the lowest it has been in over a century at 31.1—that is, roughly 31 marriages per 1,000 unmarried women.”

But it isn’t like people are dating a ton and skipping the whole getting hitched thing! We are at the lowest rate of sexual activity in American history—26% of American adults didn’t have sex at all in 2021. Simultaneously, solo weekly masturbation rates have doubled for men and tripled for women since 1992. On an individual level, people choosing not to have sex is no biggie. But when one in every four people is living celibately, and there is a dearth of heterosexual penetrative sex, we have a real problem.

The question is how do we fix this?

Well, the problem isn’t as simple as, people bone and then the economy goes up. Diverse issues like housing prices, the cost of health care, poverty, social media, and racial discrimination are all important factors in marriage rates. These are all real, and all require a complex coalition of policy makers, grassroots organizers, and individuals coming together to work out solutions.

But if you’re looking for a way to impact these issues that you can get started on by yourself, without anyone’s permission, I’d recommend building a dating app. Because so much of dating takes place online, the only barrier to entry is code. On the internet, anyone can win with a superior product, no political approval required.

There are three reasons why you should build a better dating app. The market opportunity is enormous, if you get it right you make the world a much better place, and Tinder could be done a lot better.

Market share and baby making

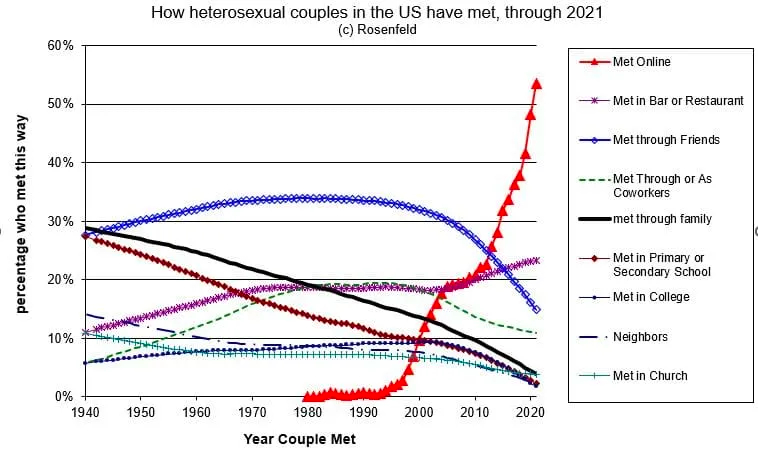

55% of heterosexual couples now meet online.

Tinder is estimated to have ~70% market share for online dating. Since Match, its owner, also has Hinge, OkCupid, and a variety of additional dating apps, we can safely assume that the company is responsible for 75% of the online couples in the United States. Since roughly 2M people get married in the U.S. per year, I think you could very conservatively Napkin Math™ your way into Tinder taking responsibility for 500K married couples—and by extension their future babies.

If you wanted to truly push the Napkin Math into silly territory, you could extrapolate that for Tinder revenue to hit $1.8B, the company extracted $3,600 of revenue per married couple. Relative to government interventions (remember Korea’s $150B in spend), this is an absolute steal. $3.6K for a baby or two is exponentially cheaper than other intervention strategies.

OK, to recap:

- People need to have babies because otherwise our economic system will collapse in on itself like a dying sun

- This is happening less and less

- It is unclear if government interventions are working

- But online dating is! Heterosexual couples are meeting in higher volumes digitally than elsewhere.

- Tinder could, with very, very, very handwavy math, provide a freshly married hetero couple at roughly $3.6K per couple.

So if this is the case, what’s the problem? Shouldn’t the government just provide complimentary Tinder profiles to its citizens and watch storks dive-bomb hospitals across America?

Not exactly.

We can do much better

In the case of Tinder, financial incentives encourage perverse patterns of behavior. The company’s best average revenue per customer is made when a user never churns (i.e., is lonely and swiping in a dark corner forever).

In this scenario, Steve would be unable to find his babe but feels like she could be found if he upgrades to Tinder Platinum for $40 a month. Dating apps are incentivized to make their customers miserable. Frankly, that the apps work so well for people like me, despite every financial reason not to do so, is a testament to how strong the fear of being alone is.

At the heart of this balancing act between despair and purchasable hope sits an AI algorithm deciding who to surface on a user’s screen. As I’ve written before, algorithm design is an editorial choice. Tinder has their thumb on the scale to surface someone who is close, but not exactly who you want.

Look—this is obviously a silly argument and my napkin math here is fuzzy at best. But I can’t help but feel that as we digitize a greater portion of our lives, an even greater portion of our souls are turned over to the machines. And most importantly, the machines aren’t neutral.

The best state of affairs for society is a dating app with high new user signups and high churn as people go off to raise children. Tinder wants lots of people to stay and never leave. So, to compete with Tinder and to drive similar levels of shareholder return, you would need to structure a company such that it captures the value of the relationships it facilitates. Perhaps that is the pairing of a dating app with a vertically integrated marriage organization marketplace like The Knot. Maybe it is an app where you integrate date planning, so you capture the value from dates 2, 3, and 4. In some cultures, matchmakers who pair up couples earn fees only once the couple enters into a relationship. I don’t know exactly what this app will look like, but that’s the point! Someone needs to go invent it.

Tinder is one of the world’s most important apps because it has the power to transform dating, boost birth rates, and strengthen the economy. However, to unlock the full potential of online dating, we must shift the focus from keeping users swiping to fostering long-lasting relationships that contribute to a brighter future for society as a whole.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!