Sponsored By: Reforge

Get hard-won insights from leaders at Uber, Slack, and Tinder

Reforge is a membership community where you can level up your skills alongside top-tier professionals in growth, product, marketing, and engineering.

By joining Reforge you get:

- a direct line to leaders driving impact at top companies in tech.

- participation in cohort-based programs

- weekly content releases and events

- a vetted community of peers solving similar challenges

Reforge’s Summer cohort starts the week of July 18. Make the best investment in your career by applying for membership before it fills up.

When we think of the things that shape who we are, a first kiss may spring to mind, or perhaps the first time you told someone you love them. Tender feelings, passionate emotions, all that garbage. These core memories alter how we perceive life around us and shape our worldview.

I have one moment that held equal import as that first, braces-filled, teenage kiss. It was the first time I was offered a chance to buy Uber stock in 2016.

At this point in Uber’s history, the company was flying high, growing faster than any startup in history, and it seemed like nothing could stop them. Everyone was dying to get their hands on some shares. A banker approached the fund I was working with, with the chance to invest in an Uber SPV at the same valuation as the Saudis’ price—roughly $62B. This was exciting! However, there was one teensy weensy detail that made me pause: I wouldn’t have entry to a data room, there would be no communication with management, and I wouldn’t even get access to an income statement. The banker was looking to raise $100M based on a logo alone.

I love this story because, to my knowledge, that money was raised within a month. It shaped my opinion that there is always a dummy with more money than you. FOMO is no respecter of income brackets.

About two years ago, I sensed a similar stirring in Silicon Valley. Like dogs in heat, investors were increasingly lusting after and losing their minds for one company: Stripe. For the uninitiated, Stripe is a payment processor valued at their last fundraise at ~$95B. The company started with the task of helping companies accept online payments and has now expanded into numerous areas.

Up until now, newsletters writing about the company have had to rely mostly on fawning praise to evaluate the company. (On a side note, it is remarkable how literally every single one of my peers has published a glowing analysis of the company). Well now, for the first time, Stripe released a few public performance stats in their annual letter last year. We can move past hyperbole to a little cold, hard Napkin Math™.

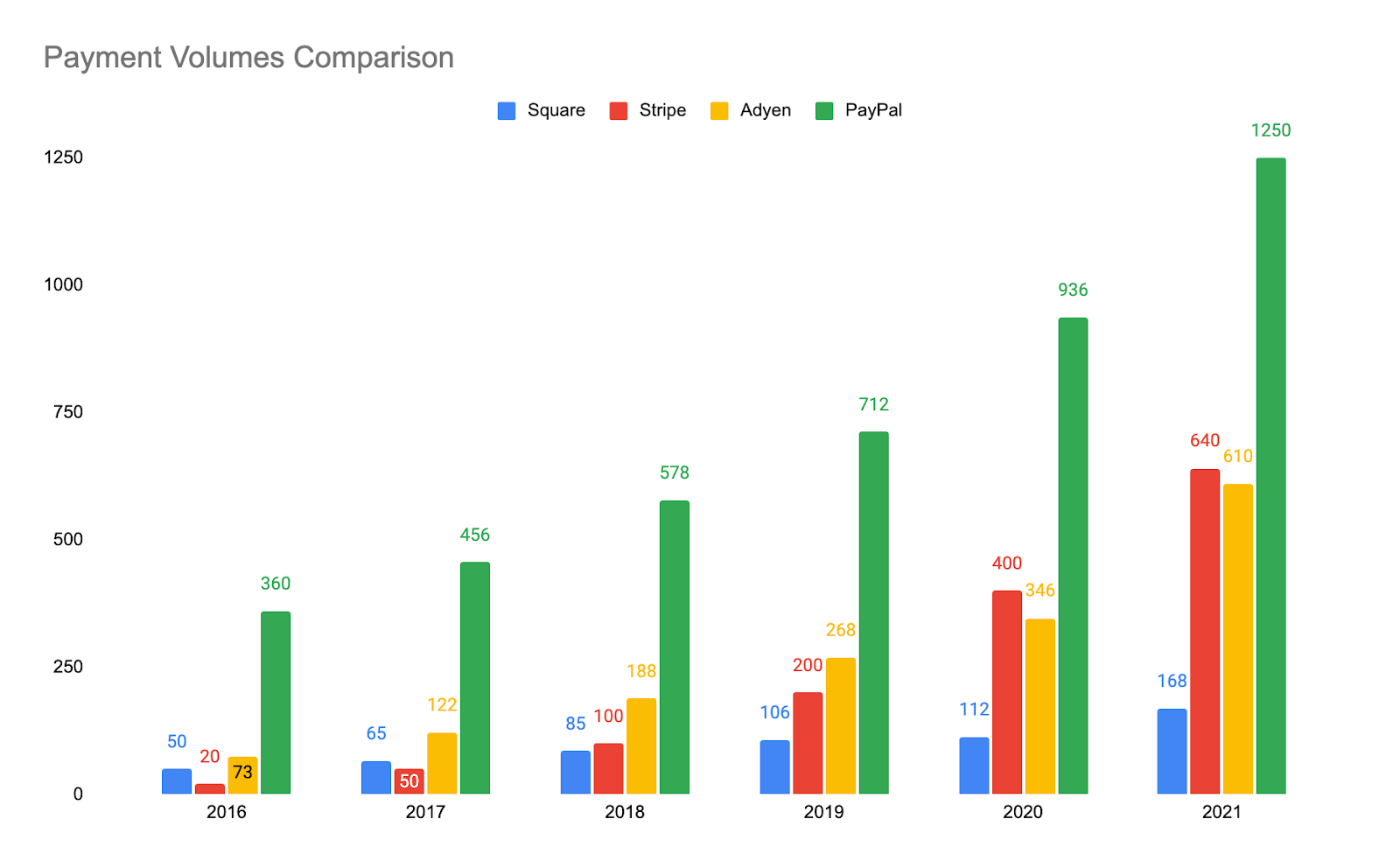

On the secondary markets, Stripe stock has been offered for upwards of a $140B valuation while the company was doing $640B in payments processing. Meanwhile, its closest peer Adyen processed $610B in payments, and is currently valued on the public markets at roughly ~$50B. This is at least a $50B discrepancy. This is crazy! Some of it is definitely driven by private investment funds having too much capital and too few places to put it (again, FOMO is no respecter of income brackets) but I think there is something more.

This discussion matters not just because Stripe is fun to ponder, but because the phenomena of valuation discrepancies between private and public markets are incredibly stark right now.

Today we’ll attempt to answer one simple question: whether Stripe deserves their private valuation. You will want to read this to get ready for their upcoming IPO.

This analysis was informed by numerous discussions with customers, former employees, and industry experts—I’m immensely grateful to all of them for sharing their thoughts. First, we should probably start with the most important question.

What the hell does this company do to justify this price?

What is Stripe

When an entrepreneur starts thinking about starting a business the conversation usually goes something like this:

Entrepreneur: “Wow I hate my job. I will literally do anything but this 9-5.”

Spouse: “Well I support you in trying to find something new.”

Entrepreneur: “Do you remember my idea for a plunger that plays music?”

Spouse: “Anything but that.”

After some rumination, the entrepreneur will come up with something that won’t embarrass their spouse and the company is off to the races. Everyone at the startup works from 8-8 (way better than the 9-5) building stuff and selling it to customers. This is wonderful and American and worthy of celebration.

However, there are a whole host of things that are absolutely essential to making a business exist, but totally unrelated to the core competency of a startup. Filing paperwork, doing taxes, buying snacks—the list goes on and on. All of these tasks end up being harder than expected and consume more energy than desired. Stripe’s original ambition was to automate one of those painful things: internet payments.

Accepting payments online is a soul-sucking endeavor. You have to calculate tax for whatever region the customer is from, convert currencies, scan for fraud, have relationships with banks, and about a hundred more tasks. All of these skills are far outside the domain of any small or medium-sized company. It is better to outsource it and that’s where Stripe steps in. It allows you to accept payments in 47 countries—all with one little bit of code. Frankly, it is magic.

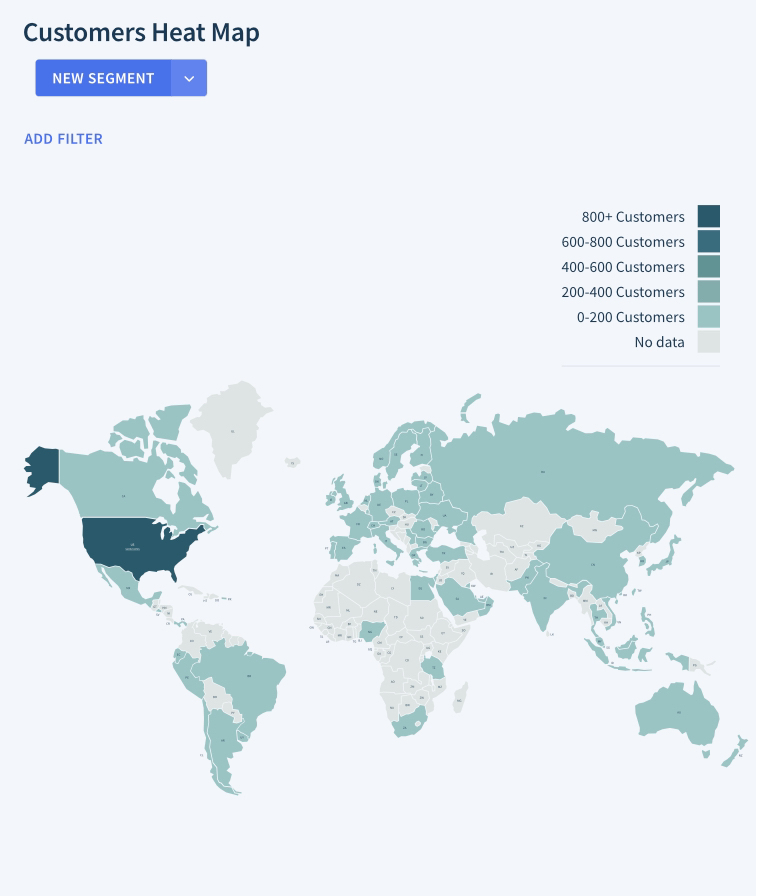

For example, here at Every we use Stripe. The integration was trivial to set up, and the map below is a heat map from a month or two ago of where all our paying subscribers were located.

From Russia to Chile to Canada, paying subscribers’ money just appears in our account.

This witchcraft happens via an API. An Application Programming Interface (API) allows developers to insert a few simple lines of code into their program that then allows them to use someone else’s application. In plain human-speak, developers could write a million lines of code telling a program to accept a payment OR they could just use a three-line API call to leverage the millions of lines of code Stripe has already written. But it isn’t just “oh let’s use Stripe’s code to make computers do stuff.” What makes this so powerful is the code also contains the agreements Stripe has in place with banks and governments. By using Stripe’s API, you instantly gain access to their partnership privileges on top of all their fancy shmancy code. An API is an abstracted layer of both computer code and human action.

By having the easiest-to-use payments API in town, Stripe makes it such that any developer can instantly integrate payments. Again, magic.

This great product is paired with a beautiful pricing strategy. Stripe charges its customers with a usage-based model. For every transaction Stripe takes 2.9% + 30¢. This allows for them to scale their average contract as their customers get bigger and will give them great net dollar retention. By being the middleman between every wallet in the world, they get to be fat and happy as the world transacts. Currently, the company can accept 135+ currencies and businesses can sign up in 47 countries. This solution was used by 60% of the companies that IPO’d last year and has enterprise size clients like Ford utilizing the product too. Of these large clients, there are over 50 who are processing north of a billion dollars of volume every year. And this is the same product used by this shrimp of a newsletter! The flexibility of the solution is impressive.

Just Pick One Thing

There’s an old Mitch Hedberg joke I’ve always loved,

“I hate turkeys. If you stand in the meat section at the grocery store long enough, you start to get mad at turkeys. There's turkey ham, turkey bologna, turkey pastrami. Someone needs to tell the turkey, ‘man, just be yourself.’”

Looking at the Stripe product page can perhaps elicit a similar feeling. Someone may feel the need to tell Stripe, “Man, just be a payment processor.”

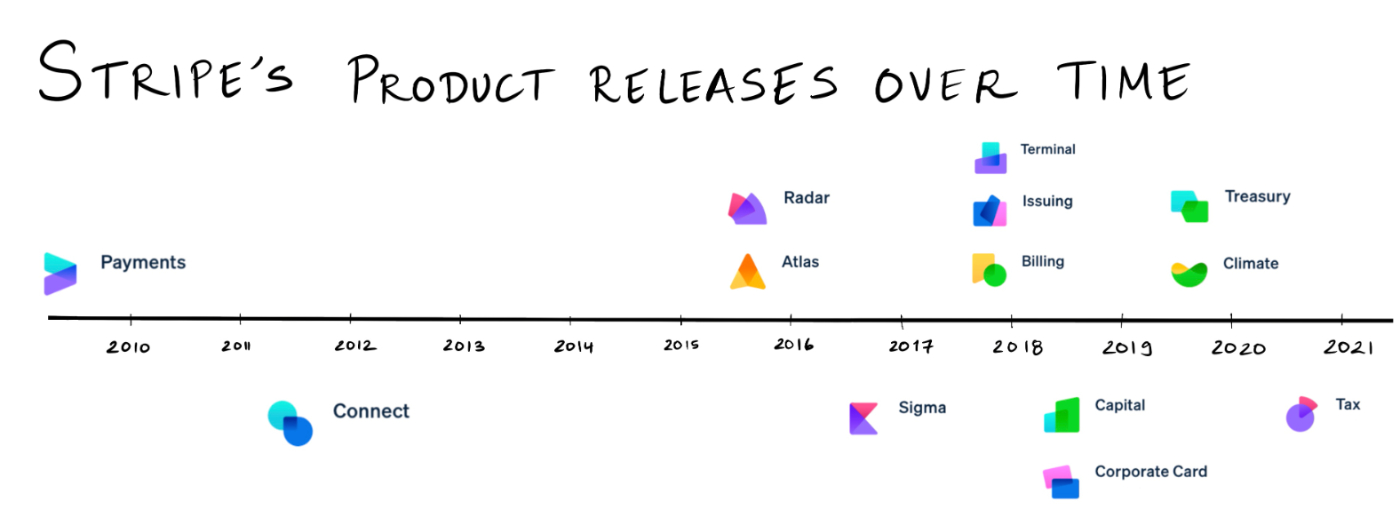

I won’t spend the time today to examine each of these products individually and how they all fit together (though if you feel so compelled to write that piece, you should send me a pitch for that!). What matters is what they do in aggregate. Each of these allows for a business to automate away a portion of annoying back-office work that has no relation to what the business actually does. Importantly, because the payments processing has established a precedent, most of these products are also priced as a % of transaction. If a merchant becomes sufficiently multi-product, the take rate can soar from 2.9% to 4%+—effectively doubling revenue. Stripe is the Captain Planet of financial products: all their different APIs combine into a super internet tax where they get a slice of every transaction that occurs over the web.

And really, the best technology businesses are built by becoming powerful middlemen. Google is an information connector and takes a small percentage of those eyeballs for ads. Facebook is a communication connector that skims some of that excess attention off the top. Amazon does the same for ecommerce and monetizes via third-party sales and ads. A truly great technology company builds the tech once and takes a % of what they facilitate forever.

This is why Stripe is perhaps the most exciting company of its vintage. Facebook, Google, and Amazon have to abstract their connections into other products like ads. No such trickery is required here. Because Stripe deals directly with money, all they have to do is take a percentage of the atomic unit that is already flowing through their system. Even more powerfully, money is infinitely flexible, so you can layer on essentially infinite products.

However, there is a downside—everything is replicable.

Stripe’s Atomic Unit

When I’m meeting with management teams to evaluate their product sense, one of the things I want to see is a deep understanding of the atomic unit of their service. An atomic unit is the most basic building block of what they are doing, the core bit of data or logic that the rest of the product is based on. As an example, a CRM software like Salesforce creates fairly unique customer profiles that are very difficult to change over.

This question matters because the more ubiquitous and interoperable the atomic unit, the more difficulty a company will have in building long-term defensive moats. If a customer can easily port your atomic unit to a competitor's product, you are forced to rely on the less-effective forms of lock-in. Returning to the example of Salesforce, I once encountered a 5-person team at a $10B public company whose job, their sole task, the sole output of 2 years of labor, was to simply change the company CRM from Salesforce to Hubspot. The atomic unit of the customer profile is not one that is easy to dislodge.

Stripe, unfortunately, has the opposite problem. There is no more universally ubiquitous atomic unit as the almighty dollar. Money’s most important property is that it is meant to be easily exchanged! The company cannot achieve lock-in by improving the atomic unit and creating switching costs based on unique data. Instead, the payments market is one that is won by execution and positioning. You can see this play out in the respective payment volumes.

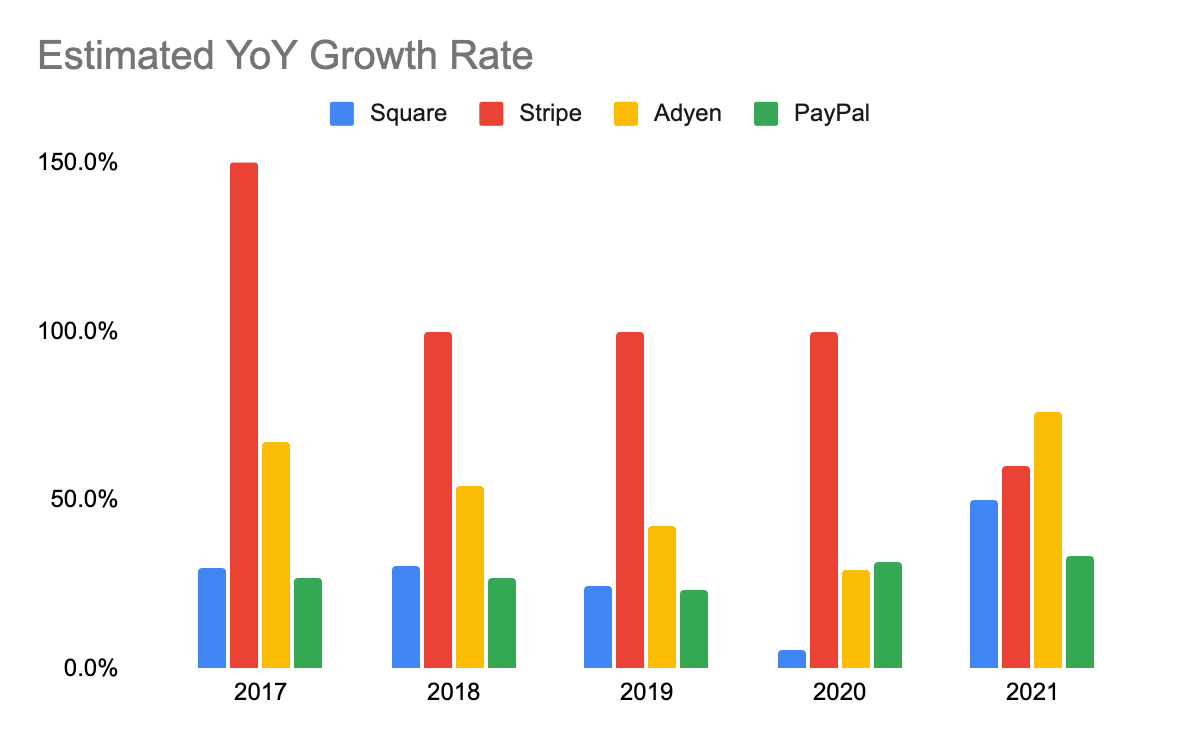

Stripe, with its developer-first, internet-native business, has been well-positioned to grow quickly as the internet transactions have taken off. But its peers have done pretty well too!

- Adyen ($~50B) is a fairly identical business with a stronger European representation and a larger focus on enterprise solutions.

- Paypal (~$100B valuation) is, well, Paypal and has been doing this for time immemorial

- Square (~$55B valuation), sorry, Block, has grown less quickly with its historic focus on in-person transactions.

But total volume may be misleading. Let’s look at how quickly each of these companies has been growing over the past few years.

Except for last year, Stripe has consistently outgrown its peers.

Comparing these businesses isn’t as easy as saying, “Ha, this company has more payment volume and is therefore better.” What truly matters is the take rate. And this is where the multi-product, API-first positioning comes into play for Stripe.

The core idea of the company is that by making a more expensive, more robustly multi-product, and developer-first product, they will be able to get a higher take rate than their peers. In a sense, they have embraced the California ethos of their headquarters: you can justify higher taxes if everything looks a little nicer.

Stripe’s $100B valuation is tricky to justify if you think of it as a mere payment processor. Its public comps are trading at multiples half as rich while enjoying growth rates in the same ballpark. But that isn’t the bet that investors are making.

Instead, it is a bet that Stripe can build their payment processor 2.9% take rate monolith and simultaneously layer on more and more best-of-class products to create a higher tax on the global internet infrastructure. With only 12% of global GDP occurring online, there are massive economic tailwinds that will reward someone who can connect all the different forms of fiat.

Still though, we are left with the core problem—there is nothing defensible about this market! It is a volume, low-margin game! How do you build a trillion-dollar company where money is the atomic unit?

This gamble succeeds or fails ultimately as a leveraged bet on two people—the cofounders.

Cultural Advantage

For better or worse, a startup’s culture is the reflection of its founders. In my discussions with people familiar with Stripe, the most common descriptor for the Collison brothers who co-founded the company was “special.” One investor described them as the “greatest founders since Zuckerberg.” Additional people described them as “brainy.” Interestingly, I also received the feedback, usually given with a scared look, that they were “ruthless.”

This is impressive along two different dimensions. First, being these things is great! I would also like for people to describe me as brainy and ruthless. Second, being able to give the impression of having these attributes is equally commendable. The brothers (and by extension the company) have demonstrated an ability to cultivate people’s admiration. Both the founders and the company have consistently pursued soft power that bolsters their credibility through content marketing and podcast appearances.

When an atomic unit is utterly indefensible, to keep market share you probably have to bundle services together (as we discussed above). However, the only way to win on an individual product level is to out-execute. Perhaps the most likely reason Stripe will win and deserves such a rich valuation is that they have built a culture to attract strong talent. Many of the best people I know all work or have worked at Stripe. Many of their executives are thought leaders on Twitter and consistently funnel their audience toward Stripe’s latest product. The company even invests money into having its own book publisher to further cement its spot as an intelligent place to work. Disclosure: I am an unabashed fan of Stripe Press and have several friends who have published with them.

As a further demonstration of their unique culture’s winning formula, the company releases products at a ferocious pace.

Graphic credit to friend of the publication Mario at The Generalist.

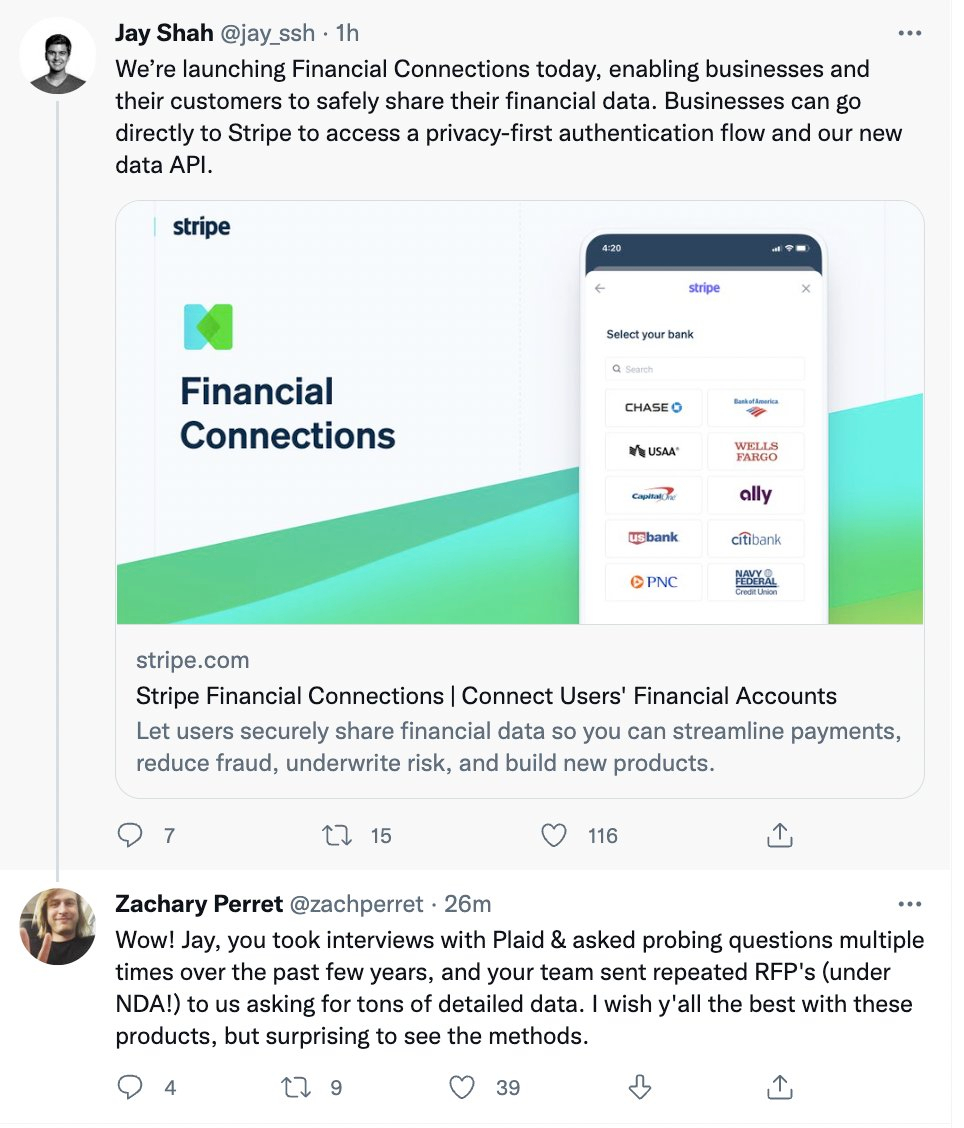

Each release is usually accompanied by a post that reaches the top of Hacker News and receives critical acclaim on Twitter. In a further demonstration of their sometimes ruthless culture, they just released a clone product of a competitor yesterday. The competing CEO was…not happy about it.

Even when Stripe doesn’t release a product that is a direct clone of another company’s offering, they still maintain an active venture portfolio of over 20 fintech startups to keep an eye on developing trends. Sometimes they may acquire them (as with Paystack), sometimes they copy their portfolio companies (like with one-click checkout), but always with an eye toward what services make sense to bundle for their customers. Note: I think all of this behavior is totally normal and fine.

Earning your Stripes

If Stripe is valued as a payment processor, $100B is probably way too rich. Comps like Adyen and Paypal would probably peg the Stripe's value around 60-70B. Instead, if you look at payments as the world’s greatest wedge that, as a side bonus, does $640B a year in volume with dozens of higher-margin products to attach, $100B starts to look pretty cheap. With rising interest rates, the company may delay its IPO, but when it does happen, I would expect the valuation to be much, much higher than where it is now.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.08.31_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!