News! I’m launching a job board specializing in aggregating roles at the intersection of tech and finance: finance, strategy, corp dev, ops, and more. Napkin Math’s 17k+ person audience includes some of the smartest people in the industry and I want to create a way to connect them to the best possible employers.

If you have an open role and want to reach Napkin Math readers you can post a job below. The best roles will go out every week in the newsletter to our audience. We’ve already got some of the best employers in the world on board.

TL;DR

- This is the first post in a new series where I examine how startups are able to build something great. These posts aren’t sponsored and the company doesn’t pay for the coverage.

- Remora Carbon signed multiple enterprise customers in its first year of existence and didn’t do anything truly unique with its sales process. Instead, it built a shared incentive revenue model, chose its first customers carefully, and attacked the global problem of climate change.

- Other startups can emulate their success by going after truly difficult problems (e.g. quit building boring productivity and workflow software).

I’ve been wanting to write more startup pieces for a long time but they are incredibly difficult to create good analysis around. The data is essentially non-existent, the narratives are constantly shifting, and you are forced into a bull case because it feels kinda bad to have a bear case on a fledgling company. People usually get around this dilemma by offering sponsored posts. CEOs will pay money for in-depth PR and in return, the writer gets access to their data (and a fat check). This isn’t something I’m interested in right now. The trust you, my readers, have in me as an independent analyst is sacred and I don’t want to do anything to violate that.

That being said, I still want to write about my first love in life (startups). The Every team and I have been noodling on how to do this right and I think we may have it. Today is my first post in a series where I analyze what makes startups successful. These posts are not sponsored and I promise no particular angle to executives. They give me access to their data and in return, they get free coverage to 17k+ of the handsomest readers on the internet. Plus they get the whole value of Evan’s brain thinking real hard about your business and offering help with stuff too. Thank you to the initial batch that will be coming out over the next 6 months. I appreciate you trusting me with your story.

Most startups are almost dead. There is a large swath of things that can kill you—Google could poach your engineers, funding may dry up, a founder might decide to do something illegal—the list is essentially infinite. One of the most obvious (and painful) existential threats is that no one will buy your product. If you are selling something to large companies that is highly technical, this threat is much larger. It is just hard to close these kinds of deals.

The response by most companies facing the “big and heavy product” problem has been to run away from it. Product Led Growth, Freemium Pricing—all of these tactics are used because they make the barrier to initial purchase that much lower. Software, with its infinite malleability and free, instantaneous distribution, is the king of this. And good for those companies! I love easy sales motions that make a lot of money. But we can’t grow crops or solve climate change or dramatically improve the world if all companies stick to what’s easy (e.g. software). It requires atoms, gritty real-world technology, and complex sales processes to change things.

The question is: how can startups actually execute those kinds of ideas? How can you avoid getting bogged down in corporate bureaucracy when selling new technology?

Typically when founders ask for my advice with enterprise sales I tell them to run away. To close big deals with major corporations usually requires a highly trained sales staff, months of effort, and thousands of dollars. Start with small and medium businesses than work your way up.

So when I met a company that had not only closed 1 but 5+ enterprise deals within the first 9 months of its existence, I decided it warranted further investigation. So today we are analyzing how this 3-employee, Detroit-based, helmed-by-a-24-year-old startup accomplished a task that takes most companies years to achieve. By aligning incentives, inventing truly novel technology, and solving a universally agreed problem, Remora shows a path for other startups to do the same.

Carbon Sucker

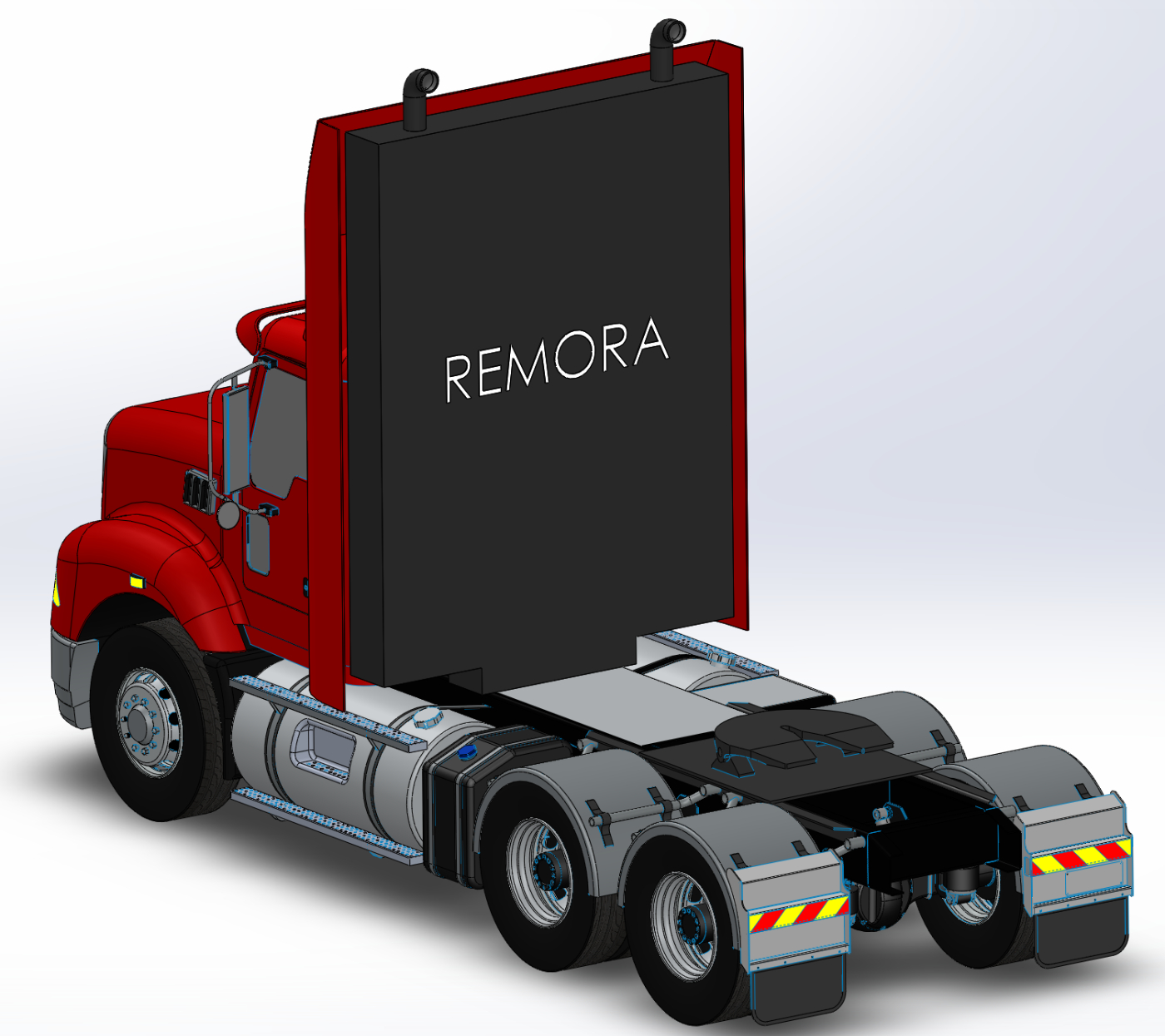

Before we can explain how the deals came to be, we need to explain the company. Remora sells a carbon capture device that is attached to long-haul semi-truck engines. It will (hopefully) capture up to 80% of the carbon emitted by the engine. The product was the result of 7 years of Phd research by Co-Founder Christina Reynolds. It still hasn’t been deployed with customers, but there is at least some scientific evidence that it will work.

Once the carbon is captured, it is sold to interested purchasers like concrete suppliers who can use it in their goods. To accomplish this audacious goal, they raised a $5.5M seed round with Union Square Ventures as the lead. Lowercarbon Capital, Y Combinator, First Round Capital, Neo Ventures, Ryder, and MCJ Collective also participated.

This is not an easy business model. Trucking companies are hard customers to sell technology like this to because they will either be massive corporations that own hundreds of trucks (with companies like Ryder as a prominent example) or very small mom & pop shops that will just have a truck or two. Remora will have to convince both of these groups to install their technology onto their trucks. These are entirely different go-to-market motions and will require very different acquisition strategies.

Each of these devices is currently priced at ~$15K. With roughly 2M long-haul tractor-trailer trucks on the road today, they have a very modest total addressable market of $30B. Note: I know, I know, this is a gross oversimplification that ignores depreciation, the increase in electrification, and that many of these trucks likely aren’t long-haul. When I think about analysis of a seed-stage startup the important thing is that the market is HUGE. How huge is a question for once the technology is working.

Once these devices are installed, the most tricky logistical component of the business comes to play: moving the carbon. The company envisions carbon sequestration stops where truckers dump out the carbon they’ve captured. Hopefully, this shouldn't take more than 5 minutes. With enterprise customers, this process is actually easy! They all have depots where their trucks refuel. It is fairly simple to stick a tank on the lot to hold carbon.

The final step of their model is reselling the carbon they have captured. Potential purchasers include concrete suppliers, bioplastics, and a variety of industrial applications. The company currently estimates that each truck should pull in $14,000 a year. Their initial pilot agreements split that revenue 50/50, but I imagine those percentages will shift over time. Note: This was the part I was most skeptical about. Find a buyer for carbon sounded really hard to me. Turns out there is a huge carbon shortage that flares up every few years.

So, in summary, for the business to be successful they have to simultaneously sell to trucking companies, set up a manufacturing line for big pieces of hardware, figure out the logistics of installing said devices, build a carbon logistics network, and then sell the carbon. You can see why people just keep making more “workflow optimization apps,” this is a lot more ambitious of a project.

So How Did These Deals Close?

When I chatted with their CEO Paul, I was surprised by how quickly he told me these deals happened. Typically when new CEOs work with large companies, you’ll see them get taken advantage of. The companies will demand equity, exclusivity, will suck all of your engineering resources, and not really care when you run out of time and die. This sounds harsh! But you have to understand that a large company will have over 450 software vendors, new startups just aren’t on the scale to matter to them.

None of that happened with Remora.

Instead, Paul reverently referred to their initial customers as “partners” and talked about how eager they were to work with Remora. None of the companies demanded equity. While there were some talks of exclusivity, all Paul had to say was “we care about stopping climate change and so we want lots of companies to have this technology” and those demands stopped.

The sourcing methodology wasn’t unique either! He just talked to anyone he knew who had a business that shipped a lot of stuff and asked for an intro to their trucking company. He then just worked his way up the chain.

To summarize, he didn’t do anything different from a sales perspective. He just sourced introductions, gave his pitch, and answered questions. So yet again we ask, how did the company land so many enterprise deals?

The Secret Sauce

1st) We win when you win

Selling a product to a company means you can really only offer two forms of value. Either you save them money or you make them more money. Cost-saving pitches are easier for customers to believe, “My software will make your machine XX% more efficient.” Telling a customer you will increase their revenue is more eye-roll inducing. Whether your pitch is that your communication tools will make the company more efficient, or that your analysis tool will empower your teams with data, unless there is a direct connection to your product and the customer’s checking account, businesses just won’t care.

Remora is able to neatly sidestep this process by selling the carbon. If they were being aggressive (and this is what I would do) they could price their hardware at cost and make all of their margin from the carbon. Nothing is more powerful than saying, “we will only make it as a company if you make money off of this.”

Find a way to pitch your product as a significant/obvious revenue win and the doors will swing open.

2nd) Pick an impossible problem

Each business has a core competency, something that they can do better than any other company in the industry. There is also a bunch of stuff that they are really bad at, but have to do anyway. Note: This is almost always HR lol. There is finally the category of things that they could never do in a million years. These are issues that are so antithetical to a company's ethos that they could just never get it done.

Big companies are always under the impression that they can just fix the stuff they are bad at. Their capital cannons are so big that they can adjust the spray of cash towards the issue and the problem will be resolved. If you don’t believe me, look at the response to Netflix. All of those executives thought, “Surely streaming can’t be that hard, I’ll just spend my way to excellence.” It has worked well for some, but in 3 years as we look at the rotting corpses of Peacock and Discovery+, the outcome will have been obvious.

Remora is solving an impossible problem for these trucking companies. Through both customer pressure and government regulations, they have been told to become carbon neutral. Electrification may offer a path, but it isn’t available in the near future. This is a company staffed with a bunch of logistics experts! Not climate scientists. The task of becoming carbon neutral is so far out of their scope that they will be forced to bring in outside vendors.

3rd) Invent some tough sh$t

The origins of Silicon Valley are rooted in physics. The early technology pioneers in Northern California built hardware that the world had never seen before. It was challenging, impossible work that would have seemed like magic to people even 20 years earlier. And while I love software (and have spent most of my career in it) there is nothing more exciting to me than scientists building never before seen hardware. It is much harder to copy custom machined parts and patented scientific processes than someone’s software product.

Inventing the future has a way of cutting through red tape. A demo that has a visceral physical component will capture everyone’s attention.

Remora has a long road ahead of it. Simultaneously building out two sales motions for both trucking companies and carbon suppliers is insanely difficult. Their pilots begin with their customers this fall and there is no guarantee that the technology will deliver. But their cause is worthy, the team motivated, and their initial start is frankly legendary. I hope they succeed. If you are interested in joining their mission, their job page is here.

This article wasn’t sponsored but I am always looking to highlight startups that are doing interesting, world-changing things. (Especially around climate, hardware, or space!) Please DM me on Twitter if you think that describes you.

If you would like to receive a weekly in-depth analysis of what makes technology companies successful, hit the subscribe button below.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.08.31_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!