Most early-stage founders hit a wall in recruiting new customers, and when that happens there are two general approaches you can take:

The first is to double-down on marketing. Some swear by ads. Others will tell you to slap an “invite friends” button in your onboarding flow, or create FOMO with a waitlist. At my last startup, an investor suggested I hire someone to join hundreds of Facebook groups and post links to our product. Growth hacking!

These tactics can be effective when paired with the right product. But once the initial wave of post-launch customers subsides, one naturally wonders, “is the product right?”

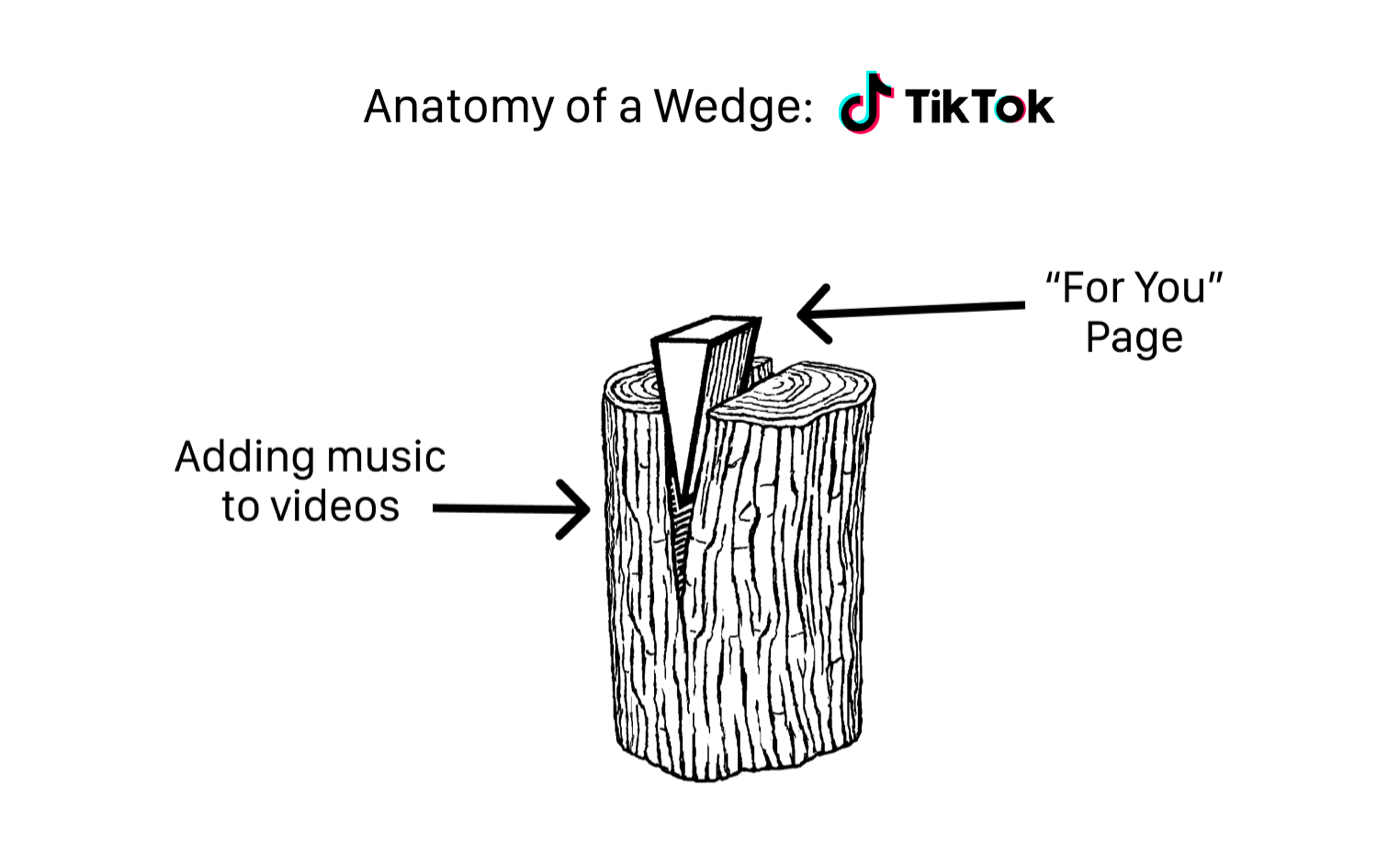

Which leads to the second approach to increase growth, changing the product. Now, you might think I’m talking about pivoting your entire company, but that’s not it. Just because your product isn’t organically taking off doesn’t mean your entire idea is bad. Maybe you just didn’t find the right starting point. So what can be done? Instead of pivoting, consider sharpening the leading edge of your initial product into the shape of a wedge.

A wedge?

Yes, a wedge! In the physical world, wedges are used to concentrate a lot of force into a narrow point, which creates a mechanical advantage that’s useful for breaking into dense surfaces that are ordinarily impenetrable.

Like, for example, the mobile video market:

Before anyone cared about blowing up on the For You page, TikTok’s initial wedge into the market was they (and their precursor, Musically) were one of the first apps to make it easy to record a video on your phone that was set to music. Teenagers came for the tool, but then they ended up staying for the network—and brought us all along with them.

This example (just one of forty-ish that we cover in this post) perfectly reflects the two core principles that make wedges work:

- Some value propositions are easier for new customers to adopt than others. To get someone to buy into the whole concept of a For You page, you need to educate people on what TikTok is and, realistically, they probably need to see several TikToks in the wild before they will be tempted to download the app. But if your friend used a tool to create a music video and sent it to you, you don’t need to learn anything.

- Some value propositions are easier for new companies to deliver than others. Even if you could get people to easily buy into the idea of the For You page, how are you going to get all the videos and data and machine learning algorithms you need to create a good experience? It’s just not possible on day one.

In other words, a wedge is a part of your early product that’s designed to help startups establish new customer relationships, by virtue of being easy to adopt and feasible for you to deliver on day one—before you have any advantages of scale like network effects, data, cash, etc. Features that make good wedges often don’t have much potential for power, in the Hamiltonian sense (i.e. they won’t support durable profitability) but, counter-intuitively, that’s actually the correct trade-off that most successful businesses often make in their early days.

The “thin edge of the wedge” strategy was initially popularized by Chris Dixon in 2010, and to me the most interesting thing about it is how almost every single successful company you can think of to some degree or another had a wedge, yet wedges are under-theorized and hardly mentioned in the traditional business school literature. Ask any entrepreneur and they’ll tell you that sequencing is one of the most important and challenging parts of starting a company, and yet there’s no solid theoretical foundation for how to sequence effectively.

In this article, we focus specifically on product wedges, but they’re not the only type of wedge. Look out for another big post on market wedges in the coming weeks.

So, here we go! This is the definitive list of product wedges you can apply to your business.

The Five Types of Product Wedges

1. Come for the tool, stay for the network

If the value users derive from a service is dependent on other people already using it, then it’s not very valuable at the early stages. Basically, network effects are great, but they have a cold start problem. One way to solve this is by building tools that provide stand-alone value, even if there is no network of users around the tool, or if the network is too small to matter. The key is to translate single-player usage into a network of some sort.

Here are some examples of tools that offered stand-alone value before they could take advantage of network effects:

- Instagram. Early on, it was key to Instagram’s growth that you had a reason to use the product in single-player mode (filters) and it let you share those photos to other networks like Twitter and Facebook where your friends could see them, and then ask you what app made that photo look so cool. But soon it stopped mattering so much that you share the photos elsewhere, and this network effect made Instagram a great business.

- Substack. When the first Substack publication launched back in the fall of 2017, the main value proposition was that the platform made it dead simple to build a paid subscription newsletter business. There was no real benefit to being a part of the Substack network, because it didn’t exist. But now Substack is working to change that.

- Nest. (Yes, the thermostat!) Nest’s original vision was to be the hub of the connected home, with an ecosystem of connected devices on one side and a network of homeowners on the other. But of course that’s a big target, so they decided to start by making a tool. It didn’t quite work, because they got bogged down in the initial wedge and failed to translate it into a network, but it’s an interesting case study nonetheless.

- Notion / Roam. They are both great single-player organization tools that are valuable when used alone, but become much more powerful when used in groups. (Come for the note-taking organization structure, stay for access to other people’s thoughts?) Notion is further ahead, but Roam is close behind and focused on a unique niche.

- Github. At first it was just a useful place for you and your team to keep your source code, but over time it became an indispensable platform that every developer had to use, because all the other developers were there. Very difficult to unseat!

- Salesforce. It started as a relatively simple cloud-based CRM, which was easy for new companies to adopt. But then the network of plugins, extensions, and consultants quickly helped entrench Salesforce as the single source of truth for a wide variety of business data.

- Shopify. At first it provided a really simple way to sell stuff online, but then as its user count grew, a whole ecosystem of plugins and 3rd party developers flourished, which made the Shopify platform more valuable. Additionally, Shopify is taking first tentative steps towards connecting customers with stores, through their Shop app.

- Figma. When Figma initially launched, they pitched it as “a design tool that works in your browser.” This was great because you can send your designs to colleagues without them needing to install software, it just worked in their browsers. Over time, as more designers specialized in Figma and tools and integrations were built on top of Figma, the network of “Figma-compatible resources” (like people and tools) became a bigger part of the value proposition.

- Every. For writers, our value proposition for now is about our editorial services, but as we grow our audience it will also be more and more about the distribution we can give writers to readers.

(Interesting side note: Product wedges aren’t just good for establishing relationships with customers, they’re also great at building new relationships with any type of counterparty: suppliers, channel partners, etc! Any partner you need to do any sort of deal/transaction with is going to be dependent on the same fundamental forces we outlined above—how easy is it for them to adopt, and how feasible is it for a startup to deliver.)

2. Come for the content, pay for the product

This is perhaps one of the most visible forms of wedges at the moment. It’s also known as “linear commerce,” a term coined by Web Smith at 2PM. The premise behind this wedge is that it’s hard to get attention with a product, but content—because it’s free and designed to aggregate attention and trust from a specific type of person—is a much more efficient route to build new relationships with users. Once people love your content and you have a way to reach them, you’ve established a distribution channel and a trusting relationship that you can use to sell a product.

- Glossier. This is the category-defining example. They started as a beauty and skincare blog, built a loyal reader base, and then borrowed on that credibility to launch a massive global beauty brand with millions of potential customers—their readers.

- Pretty much all influencers and creators. The vast majority of top creators on YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram monetize by selling products. This can be anything from t-shirts to makeup to hamburgers.

- Barstool. Whether you love or hate this abrasive sports media brand, they certainly know how to create a community. Their fan base, known as “Stoolies,” truly buys into the “us vs them” mentality that Barstool preaches, and turns to merch purchases to show their loyalty to the various personalities, podcasts, or specific accounts that they follow. In what might be the magnum opus of the brand’s outreach, Dana Bahrawy, who rose to fame off of videos of him drinking beer, managed to sell $1.5 million worth of merchandise within the first 10 days of his “Zillion Beers” line with the company early last year.

- Celeberity businesses. Kanye West is maybe the perfect example. From Grammys to Gap: the hip-hop star managed to create one of the most loyal fan bases ever assembled by consistently dropping genre defining albums and constantly staying in the pop culture spotlight. By leveraging his influence, he has been able to create a fashion empire that led to a series of massive deals with Nike, Adidas, and then Gap that resulted in him becoming one of the few hip-hop billionaires. (Of course, Kanye is not the only celebrity to leverage their audience into new lines of business. But, ya know, he’s Kanye.)

- Zillow. Started as a media site allowing prospective homebuyers to browse homes for sale, monetized by allowing real estate agents to advertise. Now they’re pivoting to actually buy and sell homes from consumers.

3. Come for curation/aggregation, stay for the exclusives

Finding stuff on the internet is sometimes a daunting task. When companies provide curation as a service, consumers flock to the product to consume the content they know they want. Curation or aggregation are often chosen by companies because it’s significantly easier and cheaper to license content than it is to produce original content. But once the company can afford it, they often begin to take risks producing their own content, with the goal of making those users loyal to the company, not just the aggregation product.

- Netflix. Started by licensing content, now focuses on original exclusive content, which is a much better business thanks to economies of scale.

- Costco. Their in-house Kirkland brand is ridiculously strong, and although most people don’t originally start shopping at Costco to access their in-house products, it wouldn’t surprise me if Kirkland is a major reason many customers choose to remain Costco members. (Another example of this type, but less strong, is AmazonBasics.)

- Roku. Following in Netflix’s footsteps, Roku is now building out “The Roku Channel” with original programming to decrease costs paid out to their streaming partners and give their users more disincentive to switch to some other streaming hardware.

- Spotify. To compete with Apple Music and the rest, Spotify is focused on exclusive content. This is why they paid Joe Rogan a bajillion dollars, and is why they recently bought a Clubhouse competitor.

- YouTube. One of the most popular aggregation services in the world, YouTube has taken the opportunity provided by having almost 122 million daily active users to launch its own series of YouTube originals. (Unfortunately, these originals don’t seem to be making that big of a difference, but it doesn’t matter that much since YouTube has such a massive network effect.)

4. Come for low risk/reward, stay for high risk/reward

When faced with two opportunities, (most) consumers will opt for the lower risk option. So when introducing consumers to an idea with plenty of risk, many companies will take the majority of the upfront risk in return for a higher return later on once the consumer has fully committed to the idea. This type of wedge is typically used in new or unfamiliar industries.

- Airbnb. On the supply side, Airbnb mostly started with people who rented a spare bedroom or even an air mattress in their living room. This is low-risk for suppliers because they can leverage an existing asset, rather than having to buy a new one. But eventually a new class of real estate entrepreneur sprang up, operating entire apartments and homes.

- Substack. For writers, Substack offers a free option that is an obvious choice for any writer who wants to grow an email list. You don’t have to quit your job or offer paid subscriptions to get started, but once you start to grow, those options become increasingly attractive.

- Sportsbooks. As sports gambling becomes legal in more and more states, a new flood of consumers are entering the market—and everyone wants their business. Companies entice these users by offering “risk-free” bets, boosted odds, or promos to lock them into their ecosystem. This gives users the confidence to take on riskier bets.

- Lambda School. Taking on loads of student debt is inherently risky, so Lambda School covers the cost of tuition until students land full-time jobs with a salary of $50,000 or more. At that point the school takes 17% of the student’s salary for two years (or until a $30k limit is reached). When Lambda originally got started, they assumed all the financial risk. But once they proved the model they were able to sell some of it to financiers and become much more capital efficient in the process.

5. Come for prestige, stay for the price

There are many businesses where it makes sense to start at the expensive end of the market and work your way down. At the top, profit margins tend to be pretty great, and you can build a coveted brand. Then you can use that cash and brand prestige to build higher-scale, lower-cost operations that can reach more customers.

- Tesla. Musk was open about his use of a wedge from the very beginning. Deeming it his “master plan”, the steps were simple: Build a sports car, then use that money to build an affordable car, then use that money to build an even more affordable car. And while doing the above, also provide zero emission electric power generation options.

- Momofuku. After building its empire off the back of award-winning ramen, the company expanded to offer more accessible (seriously, have you ever tried booking a table at momofuku?) sandwich chain, fuku.

- Union Square Hospitality. When a tJames Beard Award winning chef offers to make you a hamburger, you don’t turn it down. Union Square Hospitality leveraged their reputation as an exclusive Manhattan eatery to build a gourmet fast-food empire: Shake Shack.

- Starbucks. This coffee shop used to feel like how Blue Bottle feels to us now. And one day Blue Bottle will feel like fast food, and I’m sorry but that’s just the circle of life. I don’t make the rules.

Why do Wedges Work?

So, what do all these examples have in common? They depend on a small set of core principles, which can be divided into “demand-side wedges” (make the value easier for customers to adopt) or “supply-side wedges” (make the value easier for startups to deliver).

Demand-side wedge principles

(How to find value that is easier for people to adopt.)

- Sunk cost fallacy / consistency bias. Consumers don’t like to feel like they’re wasting money. Even if it turns out that they don’t like the initial product (the wedge), they will often continue to use the product to make sure “they get their money’s worth.” Then, in another textbook example of logical fallacies in action, if they continue to use it enough, their consistency bias will push them to believe that the product is significantly better than it actually is. This is sad but it affects our lives!

- Cognitive load. It’s easier to understand simple things than complicated things. And we are only going to adopt a product if we understand it. So a common tactic for wedges is to just be simple.

- Familiarity bias. This is why it’s better to start out aggregating, generally speaking, than it is to start out by creating. When Netflix got started they could leverage the huge canon of movies you already wanted to watch. This made it much easier to acquire customers than if they had started with originals, like Quibi did.

- Risk aversion. Doing anything new is risky. So it’s good to offer people a low-risk way to get started, then give them a path to go deeper once they’re comfortable.

- Workflow inertia. An object at rest tends to stay at rest, and people tend to want to keep doing things the way they’ve previously done them. It always helps when your product can smoothly fit into existing workflows, like how Instagram let you share filtered photos into Facebook.

Supply-side wedge principles

(How to find value that is easier for startups to supply.)

- Network effects. If you can provide functionality with stand-alone value, consumers will use your product even if the network effect doesn’t exist yet.

- Ecosystems. Sometimes you want to build a whole ecosystem of interdependent products and services. Apple, Google, and Microsoft come to mind. You can’t start by building everything at once though! It’s important to pick a starting point and expand from there.

- Scale economies. As a new startup, if you try to manufacture physical goods you’ll almost certainly find it difficult to do so efficiently, because you’re competing with businesses that have economies of scale.

- Partner prioritization. Startups often depend way more on their partners (whether that be suppliers, distributors, or any other kind of business that helps them survive) than their partners depend upon them. This means they have to conform to what their partners want, often making their product worse. As you scale this power balance can shift, and you can reap the benefits. For example, Apple has TSMC’s most advanced capabilities, because TSMC values Apple’s business much more than smaller companies.

Temporary vs Permanent Wedges

If a startup’s wedge is mostly about adapting demand-side pressures, it’s likely that their wedge will be a permanent feature of their business. For example, with TikTok, it continues to be helpful that you can share music videos to other social networks.

But some types of wedges are mostly just useful to get a business off the ground, and then are abandoned. For example Airbnb isn’t mostly focused on airbeds anymore, because they now have a healthy base of suppliers willing to provide entire homes and apartments for rent.

Here are some examples of permanent wedges:

- Gillete. Sell the razors for cheap (or give them away), make money on the blade refills later.

- Peloton. Admittedly this product isn’t the cheapest to get into, but once you’re locked into the ecosystem, you’re stuck paying a monthly fee to access its high-margin classes (or, in the case of the Tread and Tread+, to use it at all).

- Whoop. This popular heart-monitoring product sells its hardware at a loss (or makes them free with an annual purchase of the subscription), but they turn into useless jewelry if the user doesn’t pay for the software (there’s also no way to export your data to another product, a perfect example of a very high switching cost).

- Amazon Kindle. Amazon lost money on every single Kindle Fire—and yet it was worth it to the ecommerce giant because of how much money they made on ebook sales, and how much control and data it gave them on the reading market.

- Roku. This streaming giant started to work its way into consumers’ homes by selling a physical product aimed at making streaming easier. Now it makes money off of advertising, fees paid by streaming companies, and even some new original content.

- XBox. This gaming giant has admitted in court that they have never made money selling a console; much like Amazon, they make all their money off of selling games.

What is NOT a product wedge?

Initial market niche != product wedge

I bet some of you are wondering why we didn’t count examples like these as wedges:

- Uber starting in SF, then expanding everywhere

- Facebook starting in Harvard, then expanding everywhere

- DoorDash starting in Palo Alto, then expanding everywhere

- Amazon starting in books, then expanding to everything

- Clubhouse starting in exclusive private beta, and expanding to everyone

But these are just initial markets that some core technology was applied to that could in principle work in other markets. It was smart to start narrow, but the product didn’t fundamentally have to change to expand. Rather, all of these companies started in a narrowly-defined market to gain early liquidity, and work out the kinks.

We’ll talk more about this in a future post!

Cheap prototype != product wedge

Cheap minimum-viable-products are about rough, somewhat poorly-executed versions of the core value proposition. It’s early, and you want to get something out there for people to use so you can refine later. This is not a product wedge. Product wedges aren’t about rough, early versions of the same value proposition — they offer one value proposition to start, in anticipation of offering a different value proposition later.

For example, in the early days Uber’s app didn’t have many options and was kinda janky. But fundamentally you still pressed a button to get a ride. It’s the same basic value proposition today. Whereas if you look at any of the examples above, it’s about establishing new relationships using one kind of value (like content, or photo filters, etc) in order to offer those same users a different kind of value (like a product, or a network of users who you can share your filtered photos to).

“Disruption” != product wedge

Clay Christensen defines “disruption” as a trajectory of technological improvement by which new entrants can unseat established rivals. Strategy nerds might logically wonder: is disruption a type of product wedge?

For example, was “portability” the wedge that early laptop makers used to get a toehold in the PC market, before laptop sales came to dominate desktop sales? Or does disruption describe a totally different phenomenon?

While there’s certainly overlap, I think it’s important to keep these concepts separate. Disruption is what happens when a totally new way of doing things comes into the world. At first, the product or service might not be very good, but the new benefit it promises is of such high value to some portion of the market that they’re willing to sacrifice performance in the areas most people in the market traditionally value. To extend the laptop example, early buyers cared so much about portability that they were willing to sacrifice quite a lot of computing power and screen real estate.

The first laptop, made in 1981. Just look at it disrupting.

If disruption is about improving the performance of a new product to gradually overtake a market, wedges are about building a business off of one type of value then transitioning it to some other, more profitable or defensible form of value.

Risks of Wedges

Anytime you read about a business concept and all of the successful examples, it’s easy to think the strategy is infallible. Unfortunately, that’s never the case. Survivorship bias is a very real phenomenon, and it’s incredibly clear in wedges, which are most commonly used by startups. Unless you’re Quibi, a failed startup isn’t typically newsworthy.

So, what are the risks of a wedge strategy? The main one is what I call the “bank shot problem.”

What’s harder than being right once? Being right twice. Just because you get your wedge right doesn’t mean it will help you do the thing you intend on doing after your wedge.

What got you here won’t always get you there: The process of bringing a product to market is quite complex. It requires the perfect refinement of a series of interconnected decisions, from who you hire, how you price, and what your marketing strategy is, to even what your company name and URL are. To succeed in a crowded market, a small company has to be extremely efficient at solving a specific problem, and pivoting away from that to uncharted territory is a difficult task. Habits, culture, and decisions that made you successful before can even hinder your progress into a new market.

This is why the most successful wedges tend to be the most obviously connected to the bigger idea. Instagram and TikTok had a network from day one. It’s easy to see how the maker of an expensive car could use economies of scale to create a cheaper car. The Nest thermostat’s ambition to be the hub of the connected home, on the other hand? That’s a much fuzzier path.

Fuzziness is bad.

In Conclusion

Starting a business is hard, but wedges provide an opportunity to create leverage and allow companies to succeed where they might not have otherwise. They’re largely able to do this by making life easier for one of two entities: the company or the customer. If done well, it solves the biggest obstacle a company faces: securing customer #1.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!