Disruption Theory is one of those ideas that’s obviously useful, incredibly popular, and likely quite incomplete.

It’s useful because history has repeated the pattern over and over again: powerful incumbents face an existential dilemma when faced with a certain type of new entrant.

But the theory also feels — at least to me, Alex Danco, Ben Thompson, and Hamilton Helmer — like it’s not the whole story. Of course, no theory can predict everything. But at this point the list of exceptions seems to be getting rather long.

For instance:

- How does disruption explain companies like Uber and the iPhone, which succeeded by starting at the high-end of existing markets, which the theory says shouldn’t work?

- How can it account for the perpetual low-end focus of companies like Costco, Wal-Mart, and Southwest Airlines, whom the theory predicts should drift upwards over time?

- And why doesn’t the theory work when applied to certain types of high-end businesses, like luxury, fashion, and higher education, which never seem to get disrupted?

Most importantly, if disruption isn’t the whole story, then what is? What does the theory say, what are its problems, and what new ideas might make it better?

This is the first in a five-part series exploring challenges to disruption, the most popular idea in strategy.

Here’s the roadmap:

- Classic Disruption – what the idea of “disruption” really means, and where it came from. (You are here.)

- Ben Thompson’s “divine discontent” critique — are some user needs impossible to overshoot?

- Alex Danco’s “ecosystem” critique - should we view disruption through the lens of individual companies, or whole ecosystems of interdependent businesses?

- Hamilton Helmer’s razor - are “upmarket” and “downmarket” distinctions helpful? Or should we focus purely on incumbents’ incentive structures?

- The Divinations Synthesis - after weighing all the evidence and parsing all the arguments, what do I believe is true?

Sound good? Let’s get started.

Classic Disruption

Disruption Theory describes a weak spot that big companies have and a process that startups can use to exploit it.

It says that powerful incumbents tend to prioritize their most demanding and profitable customers, and move up-market over time. This leaves an opening for startups to serve buyers who require less performance, or who aren’t participating in the market at all because it’s too expensive, complicated, or inconvenient.

This would be fine, except in some markets the startups are able to improve their technology to the point where they can serve the low and high end of the markets. As these new entrants gain momentum and improve their technology, they often move up-market and become an existential threat to the incumbent.

Before Clay Christensen, most people assumed this weak spot existed because big company managers made dumb decisions. But Christensen was more generous (and realistic) than that. These same people, after all, were glorified as geniuses when their companies were on the rise! So he went looking for a more convincing explanation.

He studied industries like disk drives, steel mills, dirt excavators, and computers, and saw a similar pattern in each: leading companies often followed a trajectory of performance improvement that would overshoot their customers’ needs.

“Performance” can mean a lot of things, depending on the job customers are using the product for.

For example, when you’re using a wooden pencil you don’t want the tip to break. You don’t want the eraser to smudge. And you don’t want the point to be too big, or too small. These are all different “dimensions” of performance.

Past a certain point, you stop caring about improvements. In Christensonian parlance, you are “unable to utilize” further “sustaining innovations” — basically, product changes that increase performance along existing vectors of improvement.

The idea of a product being “too good” seems weird, but it happens all the time. The point isn’t that the entire experience is perfect, it’s that it’s good enough at one very narrow and specific dimension of quality, like, for example, the amount of smudge the eraser makes. There could still be other sub-optimal qualities — like the fact that you have to rub an eraser against paper at all instead of tapping a “backspace” key — but at least on that one narrow metric you don’t need it to be any better.

Once a company realizes they’ve overshot what customers want, they need to find other attributes that aren’t “good enough” yet to improve, or focus on cutting costs (because people would always like to spend less money).

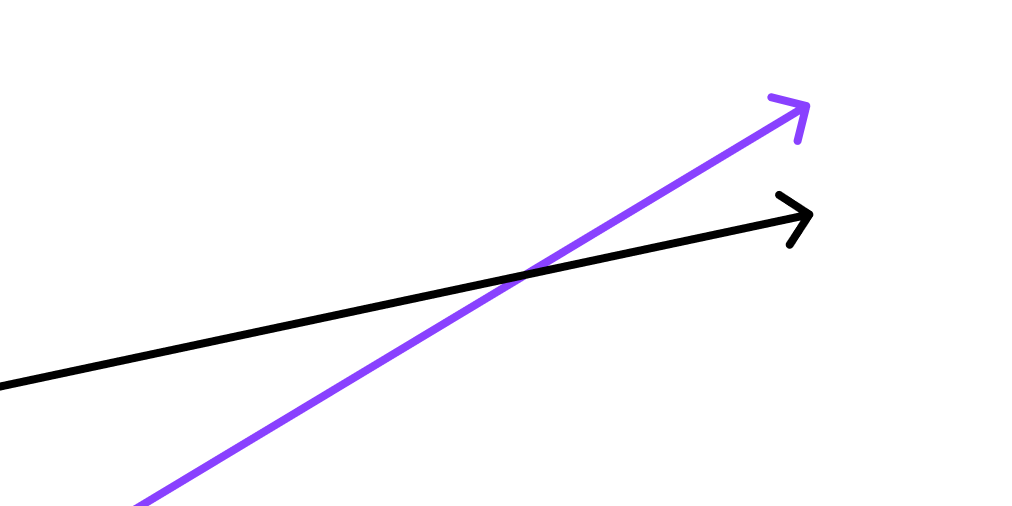

This is fine, right? They can just adjust as they go? Not exactly. Because there’s not a single unified “demand for performance” at any given time. In reality, different customers have different levels of demand. It’s a probability distribution.

And, according to the theory, most companies don’t notice until they’re far away from the middle of that spectrum.

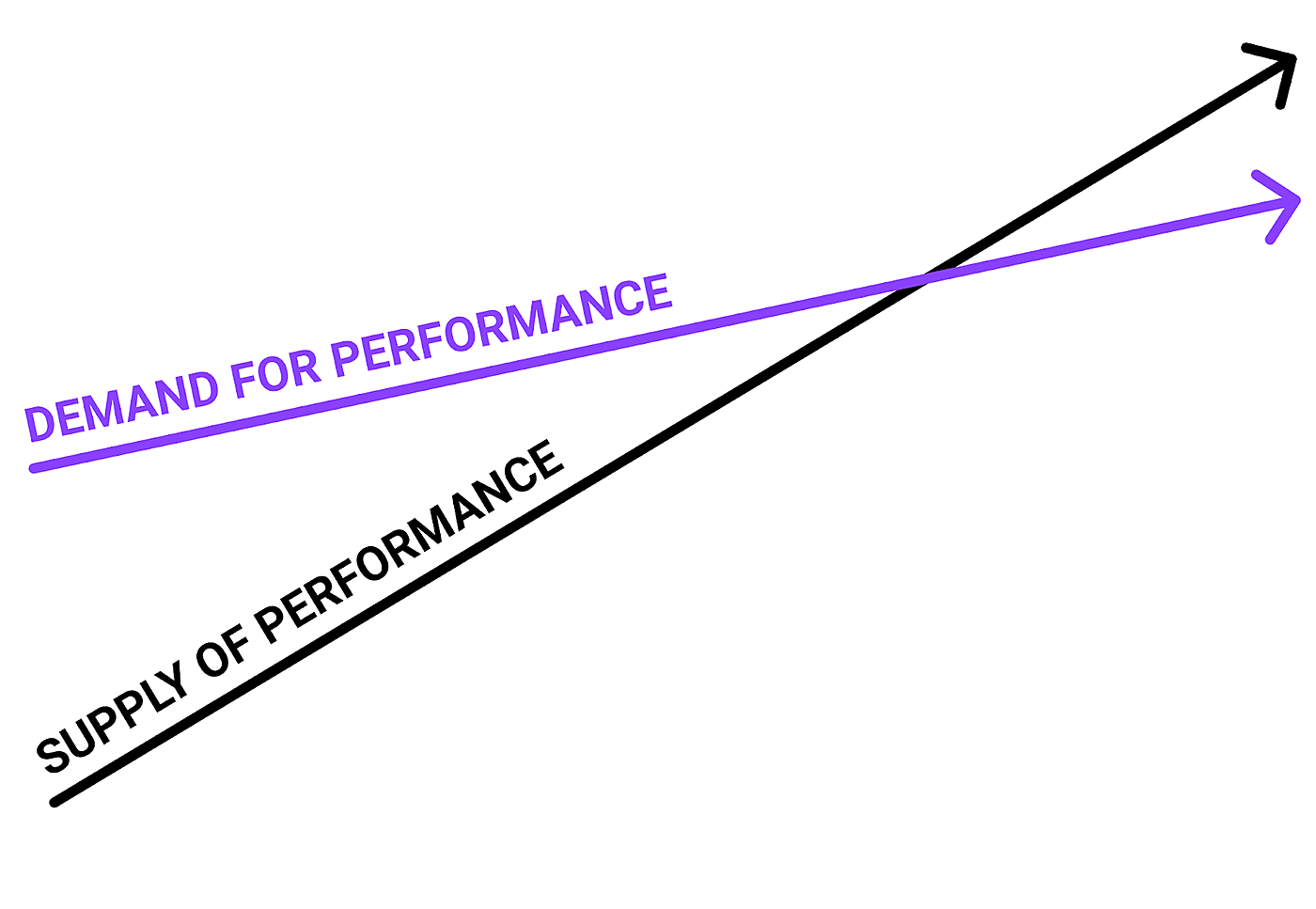

According to Christensen, most companies drift up-market for three reasons:

“Three factors — the promise of upmarket margins, the simultaneous upmarket movement of many of a company’s customers, and the difficulty of cutting costs to move downmarket profitably — together create powerful barriers to downward mobility.”

In reality, the distribution of demand for performance looks more like this:

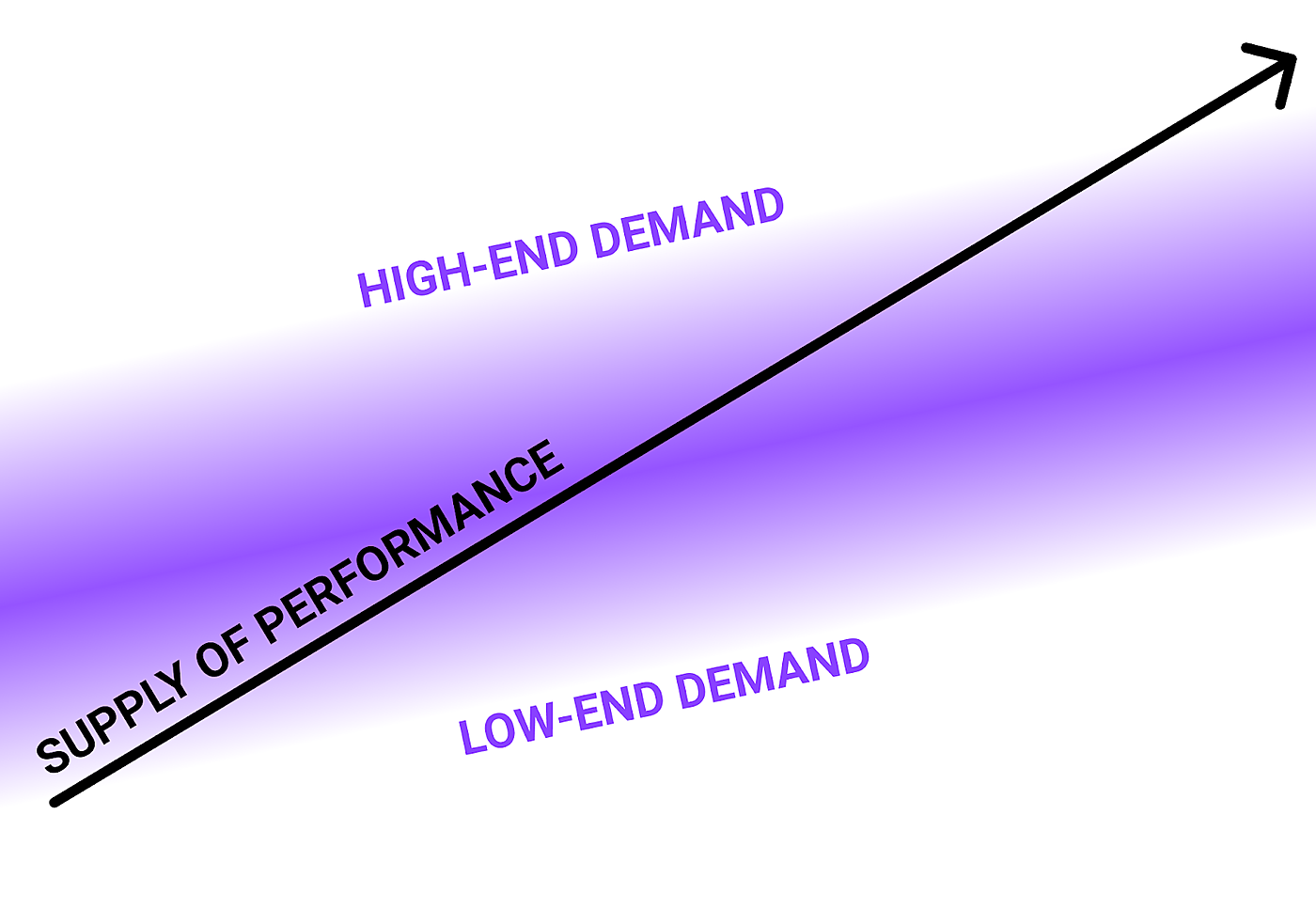

A high-end segment of customers that keeps demanding more creates the incentive for the business to keep moving upmarket. But many potential customers get left behind. The product gets too expensive and complicated for them. This creates room for a new startup to come along and serve this segment with a simpler, cheaper product.

At first the new product is only useful at the low-end of the market, and the incumbent is quite happy to give it up to the new startup. Those are its worst customers — they’re always complaining about price increases and don’t seem to value all the new and improved functionality.

But, over time, the disruptive startup keeps improving and moving upmarket. Until one day when the startup gets right to the core, and makes the incumbent’s market dry up almost completely.

The classic example of this is in the computer industry, where smartphones disrupted laptops, which disrupted desktops, which disrupted mainframes. But Disruption Theory isn’t limited to computers. It’s been used to explain everything from furniture (Ikea disrupted traditional furniture galleries) to computer storage (SSD hard drives disrupted spinning disk drives) to knowledge (Wikipedia disrupted Encyclopedia Britannica).

These examples are old, but it still happens all the time. One nascent example is Clubhouse, a new social audio app which could partially disrupt podcasts. Another is the entire “passion economy” space, which could disrupt everything from coding bootcamps to the gym.

Startup founders and investors love disruption theory because it gives them a playbook: find an incumbent who has made their product too expensive or complicated, then make a version that’s simpler and cheaper, but better along some new dimension. Then, launch to a previously ignored audience, and improve the experience over time.

This isn’t necessarily a bad way to go! But, increasingly, the smartest thinkers in modern strategy are questioning whether the playbook always works.

Complicating the narrative

The problem with disruption theory is that it’s too specific. It’s a pattern that has happened fairly often, but there are enough examples of it not happening that you wonder whether you can rely on it.

A few examples:

- Some businesses start and stay at the low end of the market. Southwest Airlines, Costco, and McDonald’s have no aspiration to go upmarket and charge more. Sure, they want to improve performance, but they are committed to keeping their prices low. And it works.

- Some businesses start at the high end and work their way down. Tesla is a perfect example of this. Uber is another. Maybe Superhuman is next?

- Some high-end businesses never get disrupted. There are plenty of obvious examples in luxury and fashion. But the iPhone and gaming consoles are another, slightly more utilitarian example.

Clearly something is going on here. And it’s not just an uninformed observer misunderstanding the theory — Clay Christensen himself had some famously flawed predictions.

As Alex Danco recounts:

“Christensen’s public predictions about tech companies, to be honest, have been real stinkers. He famously predicted that the iPhone would fail; everyone’s heard that one. But there’s also Uber, and MOOCs, and if we go back far enough, most of the companies in his own book."

So, what’s going on here?

Different thinkers have different ideas. Over the coming weeks, I’ll be grappling with them, and creating a synthesis. The goal is to build upon Christensen’s work, and see if we can make the theory even better and more explanatory. Or at least to understand where it applies, and where it doesn’t.

How did you feel about this post?

😆 Amazing • 🙂 Good • 😐 Meh • 😞 Bad

Continue reading part two: Ben Thompson

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!