1

About 700 years ago, a boy named William was born in an English village called Ockham. When he grew up, he went away to school, and there he devoured theology, logic, and philosophy. His friends called him “William from Ockham.”

As William digested the ideas of his elders, he couldn’t resist the thought that they contained many unnecessary elements. He was a skeptic. A free thinker. He felt an irresistible urge to simplify ideas to their essence. He was the Steve Jobs of medieval Franciscan monks.

This of course got William into trouble. He was condemned by the church, and forced to plead for forgiveness in front of a papal court.

But history remembers William more kindly. A couple hundred years after he died, one of his fans coined the phrase “novacula occami” (Occam’s razor) to immortalize his signature move, and now everybody learns Occam's razor in philosophy 101. Take that, pope!

In a nutshell, Occam’s razor says “the simplest explanation is most likely the right one.” It’s not always true, but it tends to be true, because the more elements you have in an explanation, the more likely one of them is to be wrong.

I’m not sure if Hamilton Helmer had Occam’s razor in mind when he was developing the idea of “counter-positioning,” but I like to think William from Ockham would approve. Like Clay Christensen’s theory of disruptive innovation, counter-positioning tells the story of how powerful incumbents struggle to respond to challenges from new upstarts — but it does so in a much simpler way, shaving off all unnecessary elements.

Of course, Helmer assures us that he is a fan of Christensen’s work, and claims that disruption and counter-positioning are complementary theories. But if you read closely and think his ideas through, it’s hard to avoid concluding that counter-positioning contains a potent critique of disruption.

2

Counter-positioning is, as promised, a simple idea:

Incumbents wait too long to copy startups with superior business models when doing so would damage their existing business. The old adage “if you can’t beat them, join them” turns out to be easier said than done. This happens because of some combination of legitimate uncertainty, cognitive biases, and flawed CEO compensation schemes.

And that’s it! That’s the idea. Here are a few popular examples:

- The iPhone counter-positioned Nokia and Blackberry

- In-N-Out counter-positioned McDonalds

- Netflix counter-positioned HBO

- Tesla counter-positioned pretty much everybody

This is obviously quite similar to disruption theory, but way simpler. No more breakdown from an integrated to modular system. No more cheaper / worse products targeting the low-end or non-consumers. No more “overshooting performance required to satisfy the customer’s job-to-be-done”.

Helmer’s razor shaves all these concerns away.

Of course, there’s value to all those ideas. But one wonders how necessary they are, if your goal is to understand the mechanisms that cause powerful incumbents to stumble when confronted by certain types of startups. Acolytes of Disruption — myself included 🙃 — like to correct the unenlightened and say things like, “well actually the iPhone wasn’t disruptive, in the Christensonian sense,” but if we take a step back and ask how useful those distinctions are, it’s actually quite hard to give a good answer. Maybe instead of quibbling over which successful upstarts are “actually disruptive” or not, we should adopt a more generalizable framework that explains why big companies tend to falter in these types of circumstances, and doesn’t conflate a bunch of other related ideas.

Theories are useful to the extent they explain and predict reality, but the more complicated and specific the theory is, the less often it will yield useful predictions. Helmer’s theory of “counter-positioning” is more powerful and generalizable, because it’s more simple. It explains why products like Tesla, Uber, and the iPhone feel disruptive despite starting at the high-end, which makes them technically not disruptive.

Perhaps the most important thing about disruption was the disincentive for incumbents to respond, and all the other stuff just describes a subset of specific ways that can happen. Useful, perhaps! But not required, and not comprehensive.

3

The overlap between disruption and counter-positioning is so obvious that Helmer dedicated a short section of his book, 7 Powers, to compare and contrast the two ideas.

In it, he makes a surprising argument, which is that disruption is not actually a subset of counter-positioning, as I originally thought. Instead, he claims that there is a “many to many” mapping between the two ideas.

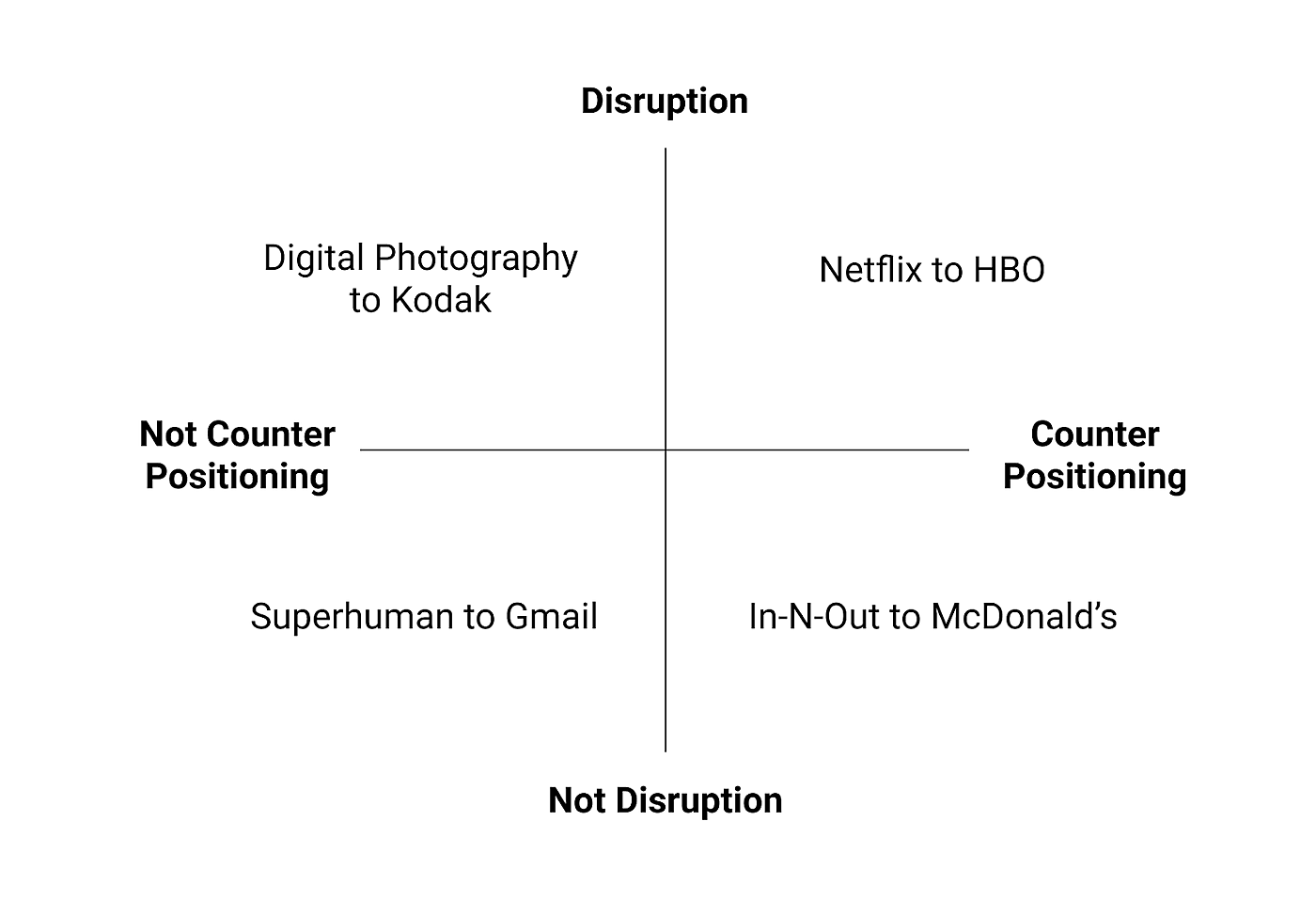

Basically, some scenarios are disruption but not counter-positioning, other scenarios are counter-positioning but not disruption, some are both, and others are neither.

Here’s a 2x2 with examples:

In other words, two two ideas are totally distinct.

The puzzling quadrant here, at least for me and a few others, is the top-left. Why wouldn’t Kodak’s demise at the hands of digital photography companies count as counter-positioning? This confused me greatly, but once I got it, it helped me understand not just counter-positioning, but also disruption, and the ways that power works more generally.

So, to get why Kodak doesn’t count as counter-positioning, let’s take a closer look at the exact definition Helmer used for the idea:

“A newcomer adopts a new, superior business model which the incumbent does not mimic due to anticipated damage to their existing business.”

The key here is the last 8 words. In Kodak’s case, they did try to mimic digital photography companies. In fact, they spent “lavishly” to find a bridge to the digital era, and they were under no pretense that their existing business was worth protecting. They tried to respond! But nothing worked.

I was honestly frustrated when I first read this. Why not include cases like Kodak as a part of counter-positioning, and just let it be a clean superset of disruption? At the end of the day, startups want to understand the conditions that enable them to topple incumbents, so why not count the startups that toppled Kodak?

But the more I thought about it, the more I came to appreciate the clarity Helmer’s more strict definition offered. The point of counter-positioning is to isolate a force that hinders competition from arbitraging your profits away. The essence of this force is that the competition is disincentivized to respond. It makes no sense to lump in scenarios where the incumbent actually tries desperately to respond! In those situations this power is obviously not at work. If the competitor can’t succeed in co-opting the startup’s model, it must be for some other reason.

So if you want to understand the reason Kodak failed, don’t look to counter-positioning. Instead, look at some of the other 6 powers Helmer identifies in his book. For example, perhaps Kodak didn’t have the expertise and cultural DNA that other digital photography companies had, and as those startups began to succeed it became even harder to copy them, because they were able to defend their position using their network effects, economies of scale, brand, and/or switching costs.

Each of these is a form of power that allows a company to resist competitive arbitrage, and maintain profit margins over time. They’re all fascinating in their own right. But that is a topic for another post.

4

There’s a lot to love about Helmer’s approach to diagnosing strategic puzzles. I wouldn’t be surprised if founders and investors begin to reach for counter-positioning more often than disruption when they want to understand how startups can resist being squashed by huge incumbents.

But it’s important that we not gloss over the many and substantial contributions Christensen made to strategy. And even if disruption is a relatively more specific scenario than counter-positioning, that doesn’t mean it’s not useful. The Christensonian universe of ideas will remain essential for decades to come.

But I think they’ll mutate in response to new theories. And so it’ll be interesting to see how ideas like “jobs-to-be-done” and “overshooting performance” integrate into Helmer’s frameworks. This work, surprisingly, doesn’t exist. At least as far as I know.

How exciting! 😀

What did you think of this post?

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!