Welcome to part 2 of my series on disruption theory!

In part 1, I laid out the classic version of the theory, as Clay Christensen articulated it in the 90s. So now we’re ready to meet the challengers.

First up, of course, is Ben Thompson. He’s the author of Stratechery, creator of “Aggregation Theory”, and the undisputed GOAT of strategy newslettering.

To be clear, Ben Thompson is a huge fan of Clay Christensen. He’s said he thinks disruption theory is “95% right” — but the other 5% must be pretty important to him, given that he’s been developing a critique of it ever since he was a MBA student back in 2010; three years before he founded Stratechery.

Here’s a timeline of this train of thought:

- Apple and the Innovator’s Dilemma, 2010

- What Clayton Christensen Got Wrong, 2013

- Obsoletive, 2013

- Best, 2014

- Beyond Disruption, 2015

- Divine Discontent: Disruption’s Antidote, 2018

There’s a lot of material here, but thankfully it all revolves around one really simple idea:

What if some things can never be “too good”?

1

A core pillar of disruption theory is the belief that technology tends to improve past what people need. Whenever this “too good” circumstance happens, an opportunity emerges for disruptors to gain a foothold in the low end of the market with a different kind of product. Specifically, a modularly assembled product, rather than an integrated one. Let me explain what that means.

In the early days of a new product category, the pioneers tend to be highly integrated — meaning, they prefer to develop lots of stuff in-house. This happens because they need a lot of control in order to figure out how a new thing should work. The canonical example of this is IBM, which when they originally developed the computer did literally everything in-house.

But over time, the architecture stabilized and it became possible for specialists to enter the market. There were companies that just made software, and other companies that just made hard drives, and CPUs, and memory chips, etc. The system “disintegrated” — it broke down from an integrated architecture into a modular one.

This happens because modularization has three core advantages, according to Christensen. When it was just up to IBM to make the software, users had extremely limited options. But once anyone could make software, users had lots of new choices! The same pattern of increased choice and personalization was replicated in other parts of the system, so customers could tailor the machine to suit their needs more easily — all they had to do was swap out a component.

There’s a second benefit to modularization, too: increased speed of development. When there’s a market of several companies all competing to ship the next generation of CPUs, you often get faster progress than if one company is trying to do everything.

A third benefit is decreased cost. Usually companies are more efficient when they’re narrowly focused, and have less overhead costs.

But there is one big drawback: modular systems don’t always work. Nobody controls the whole system, so they’re quite prone to jankiness.

A great example of this is Windows in the 90s. Microsoft made the operating system, but they didn’t control the computers it got installed on. So when computer makers decided to load a bunch of stuff (affectionately known as “craplets”) onto their machines before selling them to customers, they couldn’t do anything about it.

But consumers put up with it, because of the power of the modular architecture. Windows worked well enough, it had a huge selection of apps that ran on it, and every hardware maker supported it. All the best hardware components (like Intel) primarily were designed around it. So you had fast, cheap machines with tons of programs made for it. A little pain around the edges was better than living the painful and isolated life of a Macintosh user.

2

Clay Christensen says that when performance of the integrated system is “good enough” that’s when the modular competitors have an opening.

But what if “good enough” never happens for many customers?

This is what Ben Thompson says is the case in product categories like smartphones, clothing, cars, and gaming consoles. The thing these all have in common is they’re bought by individual humans, not businesses. The user is the buyer, and so the decision is based on what people feel they want, not what a checklist of features says they need.

And what people really want — infinitely want, Thompson says — is a good user experience.

It’s the imperceptible details that matter here: the kerning of the typography on the package; the perfectly timed animation; the perceived radiance of the colors; the feel of the thing in your hands. These are the things people truly care about, even though they can’t put it in words. They’re also the kind of things integrated providers are best suited to provide.

Quality requires control. And assemblers of modular subcomponents by definition don’t have as much control as integrated providers do. So they will always have an inferior user experience, argues Thompson.

In his words:

“The attribute most valued by consumers, assuming a product is at least in the general vicinity of a need, is ease-of-use. It’s not the only one – again, doing a job-that-needs-done is most important – but all things being equal, consumers prefer a superior user experience. What is interesting about this attribute is that it is impossible to overshoot.”

That last line is most important. It’s the reason why some kinds of integrated providers never get disrupted, and the heart of his critique of disruption theory.

What does “impossible to overshoot” mean?

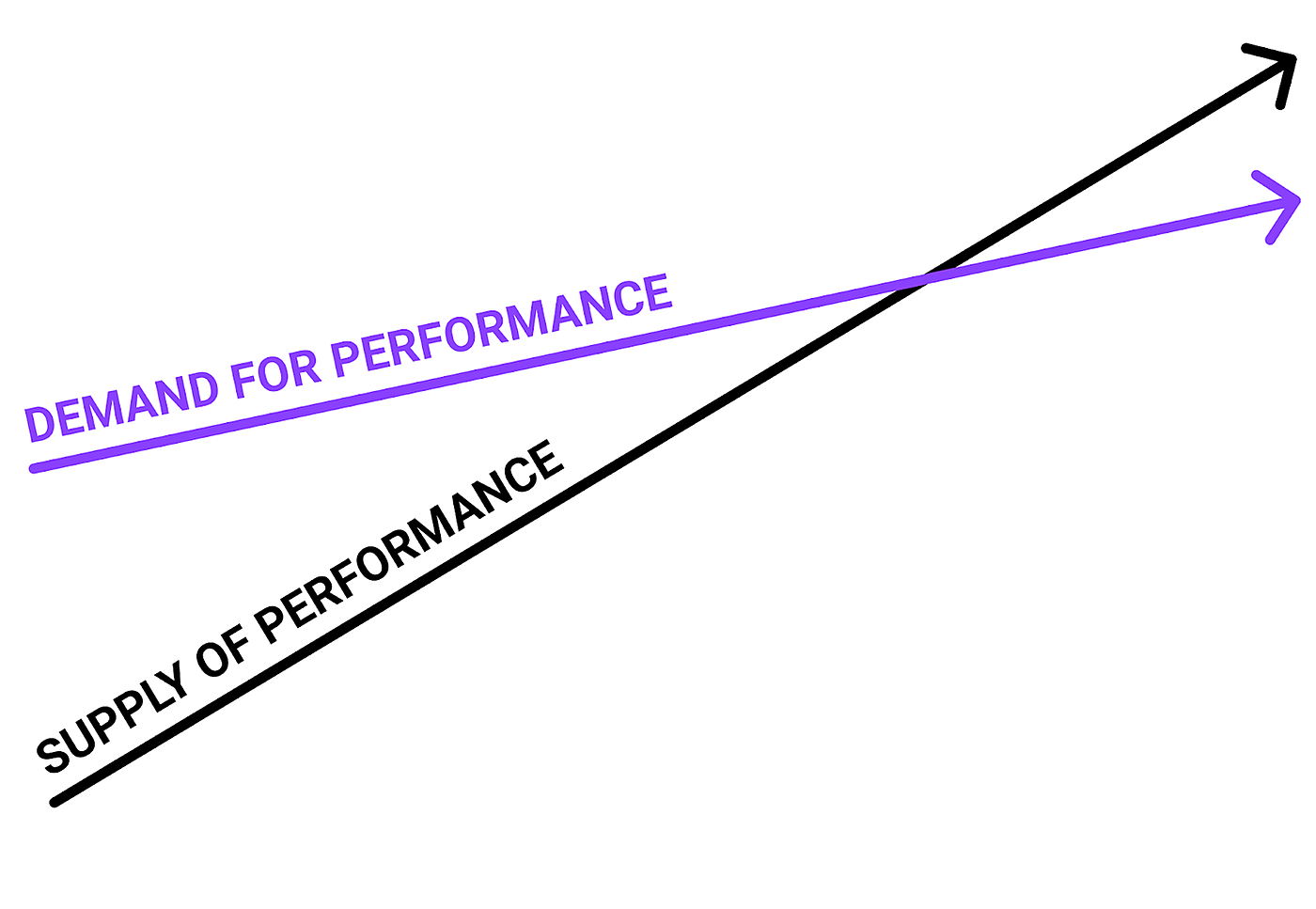

To illustrate it, let’s recall the diagram we used to visualize disruption in our last post. One the black line gets higher than the purple line, that’s when the stage is set for a modularized new entrant to disrupt the integrated incumbent.

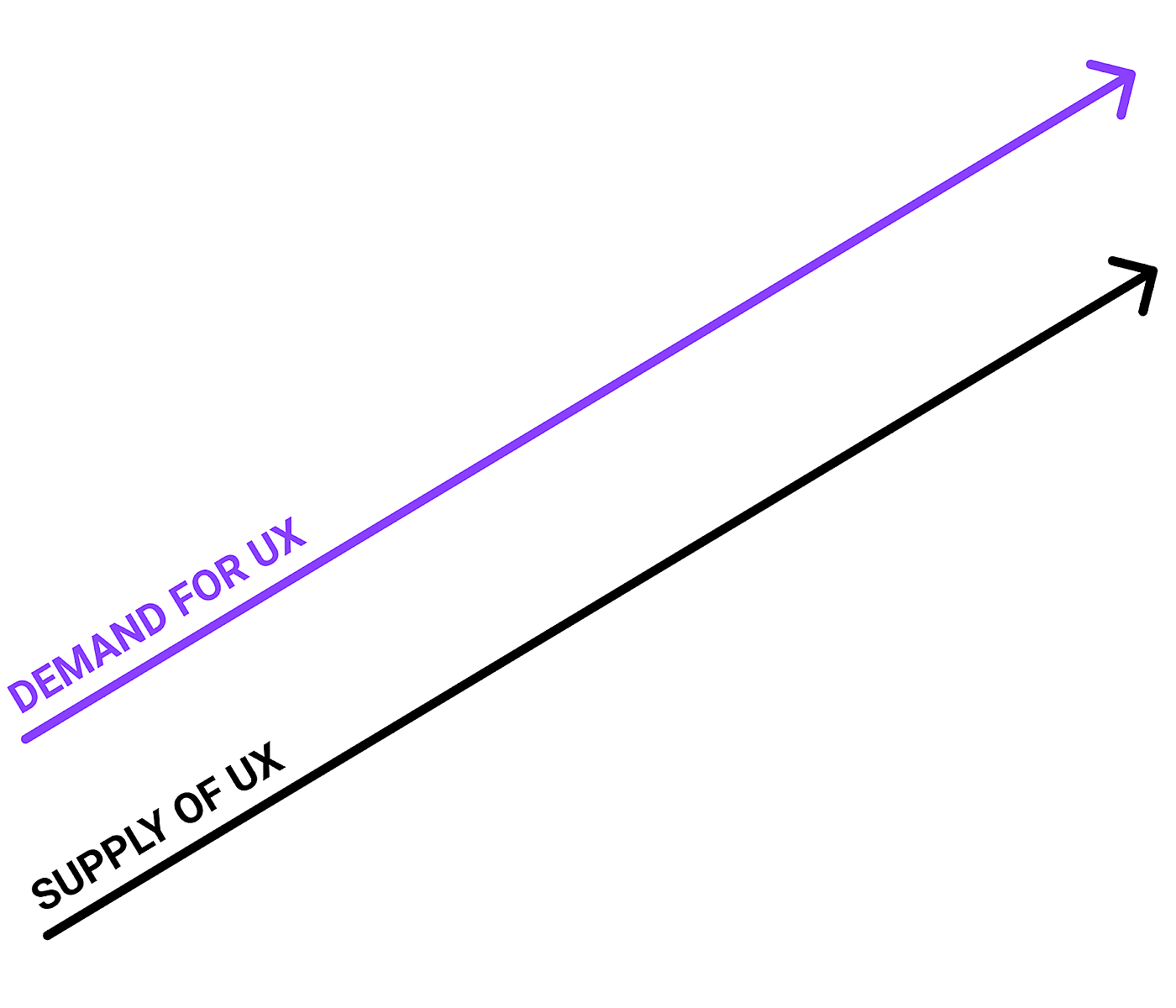

But, in Thompson’s mind, if you could quantify the performance of something as fuzzy as “the user experience,” it would look like this.

It would be impossible to overshoot:

Why is this? How could anything be impossible to overshoot?

A few years later, he elaborated on the idea and explained:

“Consumer expectations are not static: they are, as Bezos memorably states, ‘divinely discontent’. What is amazing today is table stakes tomorrow, and, perhaps surprisingly, that makes for a tremendous business opportunity: if your company is predicated on delivering the best possible experience for consumers, then your company will never achieve its goal.”

What this means is simple, but important: every time an incumbent like Apple introduces an improvement to the user experience, many of their users quickly adapt. It’s like a hedonic treadmill — you get used to it. And then all you can think about is the next thing.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean every customer in the market feels this way. But it’s true of a big enough subset of customers that it supports a business as large as the iPhone.

There’s just one problem.

3

Nobody values anything infinitely.

People have limited resources. They’ll only part with them if they feel the trade is worth it. If we cared infinitely about the user experience, we’d pay infinitely. And of course we don’t, so we won’t.

As a thought experiment, let’s imagine Apple launched an iPhone that had 10x cell data speeds, 10x storage, 10x processor speed, and 10x photo megapixels and screen resolution. Oh, and it cost $10k (10x the current price). This would be an amazing device! But hardly anyone would buy it.

Now, to be charitable to Ben Thompson, I don’t think he literally means that the user experience is “impossible to overshoot” (even though that is what he literally said). Perhaps if pressed he would clarify and say that the user experience is important enough to some people that they’re always willing to pay a premium to get the best device, within reason. And that their expectations keep shifting upwards over time as new experiences become possible, such that only an integrated company like Apple can keep up.

But if that’s what he’s saying, then we’re talking about a dimension of quality that’s so abstract as to be a tautology. We’re just one step away from saying, “people will buy the product that, all things considered, they believe to be the best fit for their circumstances.”

This is not helpful!

But, at the same time, there is still something valuable hidden in the idea of “impossible to overshoot”.

To make it more useful, I’d reframe it to say that some things are “consistently most important.” We don’t value them infinitely, but they matter the most. The basis of competition does not change, because no matter how good alternate aspects of performance get, they never matter more than the main thing.

For example, from my Finding Power framework based on Clay Christensen’s work, we learn how Coca-Cola has never been disrupted because it controls the integration between the layers of the value chain that are always going to be the most important: the flavor and the brand.

It doesn’t matter to most people how cool the bottle is of their third-favorite cola. They’re never going to choose it, because it’s not the brand with the flavor they like. This is why bottlers don’t have much power in the soft drink market, and soda brands do. Flavor is consistently most important.

Now, that doesn’t mean that we value it infinitely. It doesn’t mean that flavor is impossible to overshoot. If that were the case, Coca-Cola would be charging a lot more than a few bucks a pop, and we would have some pretty crazy innovation in flavor delivery mechanisms. But we don’t, because it’s not important enough to us, and Coca-Cola has learned not to overshoot what we need.

So, applying this framework to the smartphone industry, if we want to understand why Apple still hasn’t been disrupted by modular competitors, we should look at what’s consistently most important to consumers and ask whether integration gives Apple an advantage, and whether that advantage is likely to be durable.

I think people consistently want their smartphone to do a few simple things:

- It has all the apps I want

- Interfaces respond instantly

- The battery lasts forever

- Storage never runs out

- Photos and videos look amazing

- Everything is obvious

You could make this list as complex as you want, but the simple version is good enough to help us understand why the iPhone hasn’t been disrupted. Our smartphones don’t do these things yet! Even the best phone falls short. Maybe someday that won’t be the case, but it feels like it’s a long way off still. At that point, maybe a modular competitor will arise to defeat the iPhone.

Also, it’s important to remember, the iPhone is already a little bit modular! They buy critical subcomponents from other companies. They have an app store where third party developers create software that users can’t live without. There’s a whole ecosystem of accessories and integrations.

Maybe one day a phone will accomplish the list I wrote above. At that point, the basis of competition could shift. Perhaps a modular competitor will be able to supply such a phone more cheaply.

But, until then, we’ll consistently keep paying the most we can afford for the phone that does those jobs best.

Exactly as disruption theory would predict.

4

Ok I sort of lied. To be fair, even if this is what I think disruption theory would predict, this isn’t what Clay Christensen, uh, actually predicted.

Even as the iPhone kept growing each year, he thought disruption by a modular competitor (Android) was always just around the corner.

Why didn’t this happen?

Ben Thompson’s interpretation is that our demand for UX is infinite, so an integrated high-end provider is safe from disruption forever. My interpretation is that even the best smartphones still aren’t good enough — but that won’t necessarily be the case forever.

Of course, it could be a very long time. In some markets, the basis of competition never seems to change. Performance against the main need might be good enough, but that doesn’t mean that something else will ever matter more. Coca-Cola is a great example of this. The shape of the bottle will never matter more than the flavor. So Coke has all the power, because they can swap out the bottler and no one will care, but the bottler can’t swap out Coke and expect to retain their customers.

Maybe a similar situation will happen in smartphones. We’ll keep prioritizing the same things, and the integrated provider will always be in the best position to satisfy those priorities.

Only time will tell!

What’d you think of this post?

(Thanks so much for your feedback!!)

Continue reading to part 3: Alex Danco

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!