Get $60 Off Of Every

We just launched a new column on Every, and in celebration we’re giving readers 30% off of an Every subscription—a $60 savings—for a limited time. Subscribe before Monday, August 22nd and use this link to take advantage:

P.S. We ran this promo on Monday and the link was broken. Apologies for that! This one should work :)

The big idea behind last week’s post was “execution matters a lot.”

If you want to get fancy about it, you could go further and say “marginal improvements to each step in a process (like raising money, launching products, onboarding users, recruiting, etc) can compound into exponentially better outcomes.”

The example I used was a fundraising process that had a 12x better outcome given good execution, but it came from a bunch of smaller improvements made to each step along the way, like getting intros, converting them into meetings, and getting meetings to a “yes.”

This week, we’re going to go even deeper into the topic of execution and explore three big follow-up questions:

- Can we go through a real example with real numbers? Yes, we can! I’m excited about this one. In this post I share two real improvements we made to our funnel last year that compounded together to generate roughly 54% more paid subscribers for the same volume of traffic. It took our engineers like three days to ship these two things, and now for every million visits we probably generate an additional $100k of revenue! In this post I will go through all the numbers, what the experiments were, how the math works, and what important caveats you need to know before you do this in your own business.

- Given limited focus and resources, how can a company determine where improved execution will be most impactful? One smart piece of pushback I got last week was that improved execution in some areas is obviously much more valuable than others. For example startups probably shouldn’t spend much time making sure internal IT is perfected, and should focus more on product and sales. But within these obvious broad areas there are many possible choices for where to focus. In this post I use the classic book “The Goal” to give you a framework for finding the most valuable use of your energy.

- Does improved execution in one area of a business really spill over into improved execution in other parts of the business? What about businesses that are famously good at some things and terrible at others? For example, Dropbox had an amazing product but was terrible at enterprise sales and lost the B2B market to Microsoft, Google, and Box.

I’m most excited about the first bullet point here. It’s (relatively) easy to be the hand-wavy guy who spouts frameworks and abstract mathematics—generating real results and showing real data is what matters. We did this previously with my post on bundling, but it’s been awhile, so I’m excited to get back to it.

Read this (paid) post if you want to know an easy way to utilize the power of execution and how to know where to apply it.

If you're not learning, you're not doing your job. Get an Every subscription.

When you sign up for a paid subscription to Every you'll get access to:

- Every article we publish advertisement free

- Our back catalog of hundreds of essays, explainers, and interviews

- Our Discord community where you can interact directly with our writers

Every article we publish is designed to help you level up in your business and in your life. Take advantage now because we’re giving readers 30% off of an Every subscription—a $60 savings—for a limited time. Subscribe before Monday, August 22nd and use this link to take advantage:

1. How we execute at Every — a real example

One of our most critical business processes is converting people from looking at an article on the website to joining our email list. The way our article pages are designed can be executed better or worse to achieve this goal.

Here’s three versions we recently tested. All had the same design, only the words were changed.

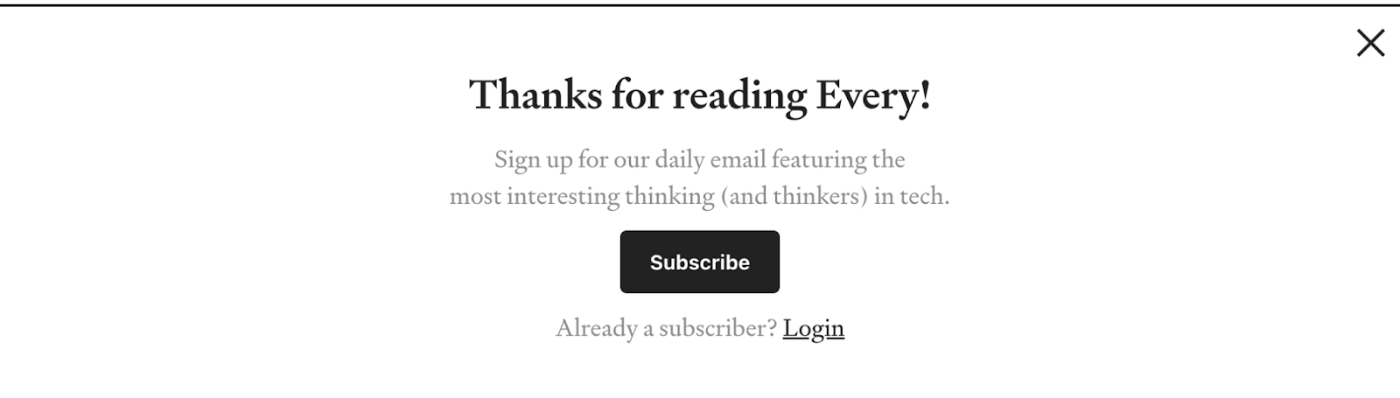

Version 1

(We stole this copy from The Atlantic)

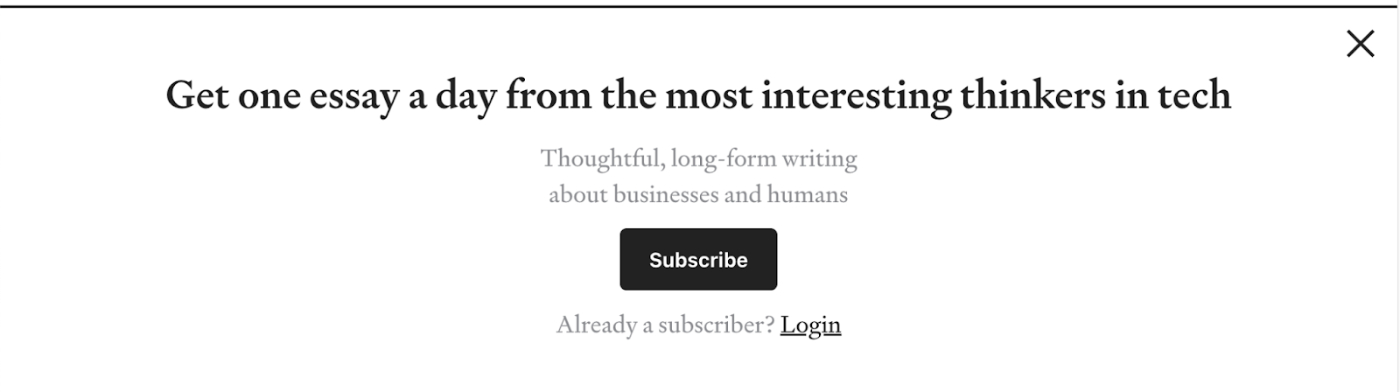

Version 2

(Focus on what the product actually is)

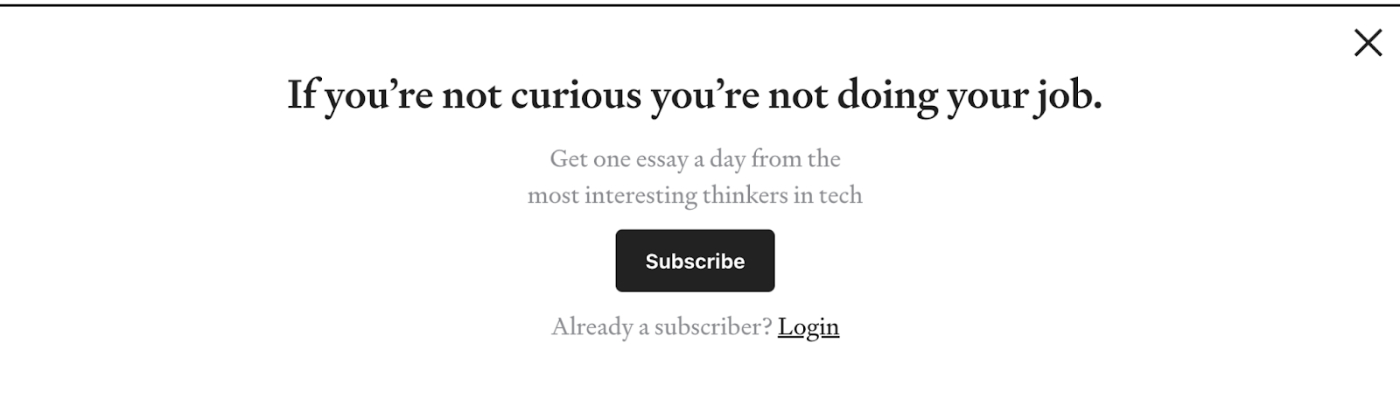

Version 3

(Focus on the larger purpose / benefit. Kinda shames people though, which I don’t love! lol)

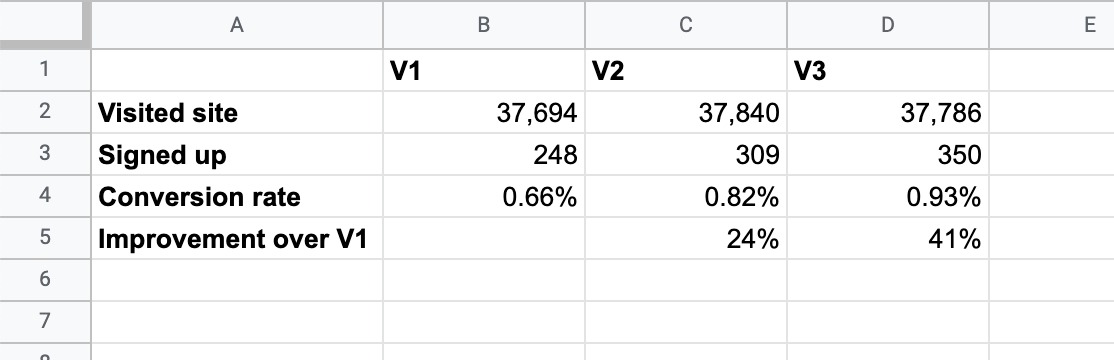

And here are the results:

We’re still waiting to get more results because the test hasn’t been running that long, but it’s pretty clear V3 (“If you’re not curious you’re not doing your job”) has a solid lead and should generate more signups in the future. If the past is predictive of the future (it’s not, and we will get to that, but let’s assume it is for now) then the v3 design will yield 41% more signups.

41% more emails is a pretty good improvement! I bet we can push it even further. We’re still converting less than 1% of visitors into signing up for our email list. We haven’t played with design changes at all yet, and of course there is the basic most important thing which is to write better articles that make people want to subscribe :)

Anyway, this all gets much more interesting when we zoom out and look at the other steps in the process of onboarding new users. Once you sign up for our email list we’d also like you to become a paying subscriber so you can read everything in our archives (and we can pay our bills and reinvest that cash in the business to make bets on more great writers). In order to do that we need to show you a screen that gets you to pay.

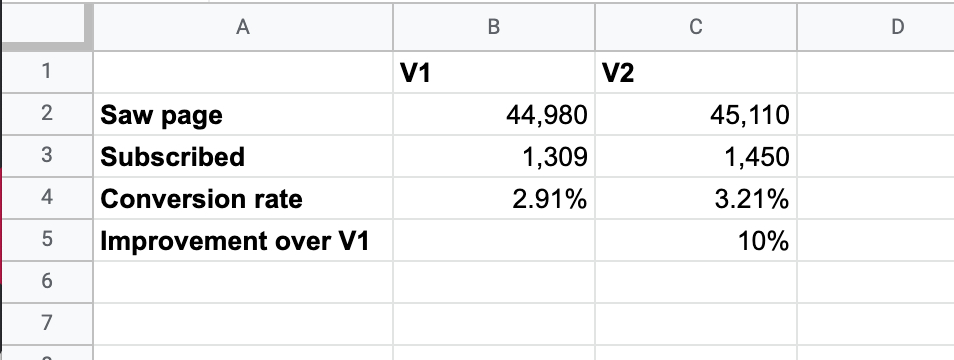

Here’s the results from another real test we did on that screen. V1 didn’t have Apple and Google pay, V2 added those options.

The new screen generated a 10% improvement in conversion from free to paid. Great!

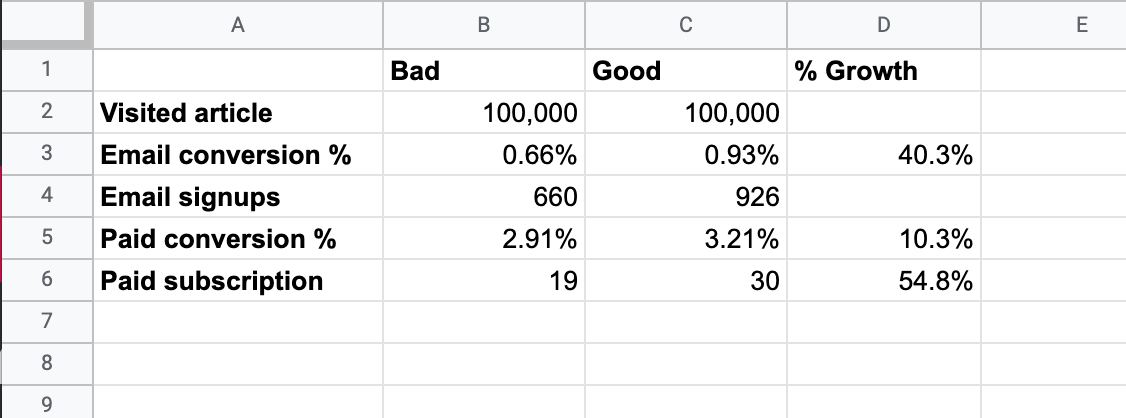

Now let’s take the lessons from these two experiments and see what happens if we combine them into one “bad” version of the funnel vs a “good” one, with hypothetical future traffic:

55% overall improvement in paid subscribers for the same number of website visitors is pretty great! It may not be as dramatic as the math from the fundraising example above, but it’s real (with the exception of one important caveat below) and it illustrates the same underlying mathematical principle:

If we string these two improvements together, 40.3% and 10.3% in this case, the overall improvement is equal to multiplying the two improvements together: 1.403 * 1.103 = 1.548. In simpler language: marginal improvements have a multiplicative effect.

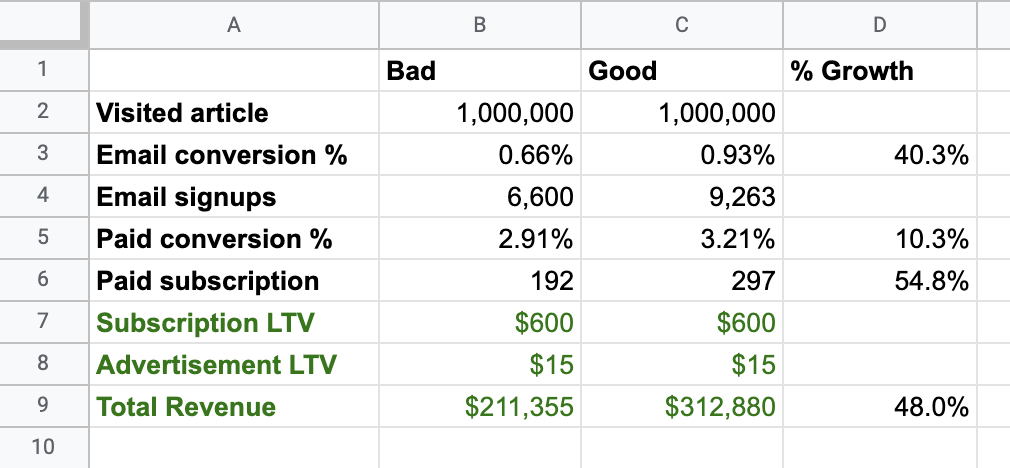

To put an even finer point on what this improvement means for us, here’s a rough estimate of how much revenue we could generate per million visits in each scenario, given a rough LTV estimate for ads and subscriptions that is in the right ballpark for us:

There’s a lot we can do with that extra $100k! And remember, we get to keep this gain (with caveats) automatically going forward in a scalable way. Shipping better copy on our article page and adding support for Apple Pay and Google Pay were one-off projects, but they can keep yielding gains for us automatically going forward without us having to do much additional work. And that’s not even taking into account other improvements in the rest of our business that can flow into this. (Like writing better articles, attracting more writers, etc.)

Before we move on, there is a really important caveat that I have to mention.

We actually don’t automatically get to string all these gains together. There are a few complications that are important to understand.

First, it’s entirely possible (and perhaps even probable) that when we increase the conversion rate from “see article to signup for email list” we simultaneously decrease the conversion rate in the next step, which is to become a paying subscriber. This could happen because the marginal emails we acquire with the new version are from people less likely to pay, and those who do pay might churn faster and have lower LTV.

But we shouldn’t throw our hands up and conclude that no optimizations are worth making. First, because we don’t know ahead of time whether improvements to one step will make the next step worse. Second, because even if the next step does get worse, it’s often not bad enough to offset all the gains. Third, because all things equal it’s better to have people on your email list than not, even if they seem to convert worse at first. Once we have a way of reaching these people (funny that I’m talking about you, readers, in the third person) then we always have an opportunity later to publish better articles that might get them to eventually subscribe.

Second, things change. The copy that converts better today might become stale tomorrow. Apple Pay and Google Pay might be great now, but other platforms could become more important in the future. Or we could keep adding more payment platforms until the page becomes a crowded mess, resulting in worse overall conversion. Because the world changes every day, businesses can never reach perfect optimization—they have to keep changing even if all they want to is keep generating the same results.

But just because A/B test gains don’t last forever doesn’t mean they’re not worth making, of course.

I just had to mention these things because they are important caveats to the simple math model I showed above!

2. How to prioritize your execution energy

There is only so much time in the day. Where should you spend it? This is the age-old question that haunts Product Managers everywhere. There are frameworks galore, but in my opinion few are actually helpful. They are fill-in-the-blank exercises that assume you already know the answer. For example, one common framework is to list the metric you think would improve if you did a project, how much it would improve by, and how certain you are that it would actually improve. Then when you multiply impact by uncertainty, you get the risk-adjusted return.

The problem is of course that you have no idea what the risk-adjusted return is, because at the end of the day you’re pulling numbers out of your ass, and the framework doesn’t give you any leverage to come up with better numbers. All it does is quantify your prior beliefs, but what we really want is a method to come up with new, better beliefs.

That’s where the Theory of Constraints comes in. It is a management philosophy created by Eliyahu M. Goldratt and popularized in his perennial bestseller The Goal. The basic idea is as follows:

The output of a system is determined by the bottleneck. If you want to improve the output, you need to attack the bottleneck until it no longer is the limiting factor, and something else is. Rinse and repeat.

Let’s make it more concrete. For example, at Every there are a few key steps that make up our system:

- Write articles

- Get people to read the articles

- Convert new readers into joining the email list

- Convert free readers into paid subscribers

- Attract the right advertisers

- Get readers to click on the ads

- Use the money we generate from subscriptions and ads to hire more writers

There are more steps, and each step can be broken down into infinite sub-steps, but this is a good basic outline of our system for the purposes of this essay.

The Theory of Constraints tells us if we want to improve our system, one of these steps is going to be the critical “limiting factor.” In other words, no matter how much we improve the other steps, it won’t make a big difference because all the improvements are being held up by the bottleneck.

In his book, Goldratt thinks about this in a manufacturing context. There is one big machine that needs to be used to create every widget, and that machine is slow and expensive. Therefore, everything should be organized so that the machine has as little downtime as possible, because the entire system can only output widgets as fast as that machine can run.

For Every, it’s a little more fuzzy but the basic principles still apply. If our articles attract very few new readers, we can technically still make more money if we do a better job with all the other steps, but it will be a small, marginal improvement compared to anything we can do to fix the real limiting factor. No matter how smooth our funnel is or how good our conversion rate is, we can’t sell ads or generate many paying subs from a small audience. So everything is basically limited by step 2: get people to read the articles.

How do we get more people to read the articles?

- Writing better articles

- Attracting more good writers

- Promoting our articles in better ways

Those are the big categories, but again each of these is massive and contains many worlds of sub-optimizations. For example, within “writing better articles,” there is:

- Improving topic selection

- Writing better headlines

- Talking to people who know unique things

- Getting better feedback from each other

- Learning more from the data on our existing articles

And within each of these bullet points there is again infinite complexity. It’s like a fractal: you keep zooming in and you keep seeing more sub-components.

The cool thing about the Theory of Constraints is that it helps you no matter what level of zoom you’re at. For example, taking the list above of ways we can improve our writing, which one of these is the bottleneck? Headlines are huge, because if the headline and top of the article doesn’t suck you in, then you won’t keep reading to the bottom no matter how good the rest of the article is. But upstream of headlines is topic selection: no matter how well-written a headline is, if it’s not about a topic that’s interesting to you, you’re not going to care.

It’s beyond the scope of this article to get to the bottom of exactly what Every should do to get more people to read our articles, but the reason I wanted to show this is to illustrate the type of thinking you can do about your own business, using the Theory of Constraints.

In a way, this is where strategy meets execution. Deciding what to execute better on is a strategic decision. It’s also an art. There is a ton of uncertainty, so it’s better to move fast and try things than to debate endlessly. (I am guilty of this! Honestly it’s probably why Substack let me go. But I am starting to get better!) This is also another reason why experience helps: you already have an intuition of what matters that is close to reality.

One last thing before we move on to the final section: this may help answer a little weird thing that some of you may have noticed from the first section. I mentioned that it only took our engineers a few days to ship the two product experiments that resulted in a 54% increase in paid subscribers. If that’s possible, why don’t we see similar gains every single week? Why can’t we 1000x it over time? The answer comes back to the Theory of Constraints. We can’t ever convert more than 100% of our website visitors to paid subs, so there is a pretty hard limit on the gains our signup flow is capable of generating for us. A much better use of our energy is to improve the quality of the writing and to attract more great writers, which is exactly what we spend 99% of our time thinking about.

3. Does good execution in one area really spill over into other areas of a business?

Last week I said:

“Good execution in one area tends to lead to good execution in other areas of the business, because good execution is only possible within a culture that permits (and even demands) excellence. Good execution leads to increased morale. The bar for everyone gets raised. The energy of good execution is contagious.”

But as some smart readers pointed out, there are some obvious counter-examples. Dropbox, for example, got initial traction as a consumer utility through incredible product execution, but had trouble breaking into the b2b market and competing with Microsoft, Google, and Box. Their product execution was so good, why didn’t the “morale” infect the sales team? 😅

This is a really good point that will help us illustrate not only a limitation of the theory, but a deeper truth behind it.

The limitation is that of course good execution at some level creates a culture that has positive spillover effects, but this happens imperfectly. It’s a force that is pretty delicate and weak and a lot of other factors can easily swamp it. That’s not to say that it doesn’t matter to create a culture of excellence—it does—but it can only take you so far and won’t solve all problems.

This leads us to the deeper truth behind the theory. Good execution doesn’t just make the business better at what it does, it actually makes it worse at doing different things. The more optimized you get at doing one thing, the more all those optimizations stand in your way when you are trying to do something else. This is why big companies are so hard to change.

Michael Porter talks about this a lot in his books. He thinks of it as being “dug in” to a specific strategic position. Businesses get specialized as they mature and create a lot of complexity that enable them to do their thing really well.

In Dropbox’s case, their version of success early on was actually a fairly different business than B2B enterprise sales. The things you need to do to make the product better for businesses would actually make it worse for consumers. The entire product philosophy might have to change: more options, more settings, more complexity.

This helps us understand the ways in which good execution spills over and where it doesn’t. I’m sure at Dropbox the great software engineering increased the energy and excitement of the product design team, and the great design spilled over into great product marketing, and great viral growth mechanisms. All of those things are products of the same basic business. But the shape you morph yourself into to capture that opportunity is fundamentally different from the shape you’d morph into if you wanted to capture the enterprise storage opportunity, which is why Microsoft and Box did a much better job.

This is of course not a hard-and-fast rule. Plenty of businesses use Google’s G Suite, even though Google started with more consumer product DNA. It would be interesting to research how and why that happened and whether there was any culture clash that made this difficult. But that’s a post for another day.

Hope you enjoyed this one! Please keep the smart feedback coming, it really gives me a ton of energy. I’m biased, but I think our little crew we have going here is one of the smarter collections of business thinkers that exists on the internet. I am really thankful for all of you.

See ya next week!

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!