Every business will, from time to time, go through rough patches. And in these moments the people who run the business are usually pretty motivated to make changes and do something about it. But the types of actions they can imagine are often limited. Whole categories of possible moves—many of which may contain solutions to their problems—are invisible to them. They don’t enter into the consideration set. In a way, these managers are limited by habit and instinct.

If a perfect AI robot manager were to take their job, I think its process for diagnosing the causes of lackluster performance would look like a decision tree. And the most important fork in that tree is to classify the situation as a “strategy problem” or an “execution problem.” In other words, do we need to do a better job of executing our current plan? Or do we need a new plan?

The more stories I hear about how companies succeed or stagnate, the more I realize that it’s extremely common for creative founders (also known as “idea people”) to have a persistent bias towards seeing everything as a strategy problem, even when it’s really an execution problem. So when we’re in trouble, we often look for the next big idea that will fix everything. We get excited about big narratives that explain where we are, why we’re struggling, and what we need to do differently in order to fix it. We get hyped to embark upon a bold new chapter—only to realize later that our fortunes haven’t changed that much, the team is starting to get tired of all the changes, and we’re running out of cash. I’ve seen it happen over and over again. I have done it myself.

A lot of times, instead of thinking big, we actually need to think small. Instead of getting hyped about broad narratives that explain our predicament, we need to just buckle down and ask ourselves how we can do what we’re already doing—but much, much better. We need to focus on execution, not strategy.

So why don’t we?

The main reason, at least in my experience, is we don’t realize just how much better we could be executing, and just how much the metrics could improve if we did. We assume we’re performing most of our key activities roughly 80% of the way to perfection, and pushing harder to get the remaining 20% wouldn’t move the needle that much. In my experience this is usually false. We may not be able to imagine how, but 10x or even 100x improvements are possible more often than we think. And the ultimate effect of making that kind of change on every activity has compounding, multiplying effects.

There are two ways of proving this and showing how it works: 1) through an example, and 2) mathematically.

First, the example. Here are three different ways of getting intros to possible investors:

This is just one step in the fundraising process, but it’s an important one. There are thousands of investors out there, and quickly finding the right ones for your company can make the difference between life and death. This is an activity that’s trivial for experienced founders. So let’s attempt to quantify how big a difference we’d see between the “poor” example and the “best” one here.

How many high-quality intros do you think the first method would yield, of just asking existing investors for intros? Let’s assume you have 10 existing investors, I think probably a couple of them might make several intros, a couple more might make one, and the remainder might not make any intros. So that’s roughly 15 intros total.

Now let’s consider how many intros you can get if you assembled a spreadsheet of relevant investors. Maybe there are 50-70 investors who could be good for your business. Of course it depends on who your existing inventors are and how extensive their networks are, but I bet most founders can get an intro to at least 30 and more often closer to 50. Investors turn out to be fairly reachable.

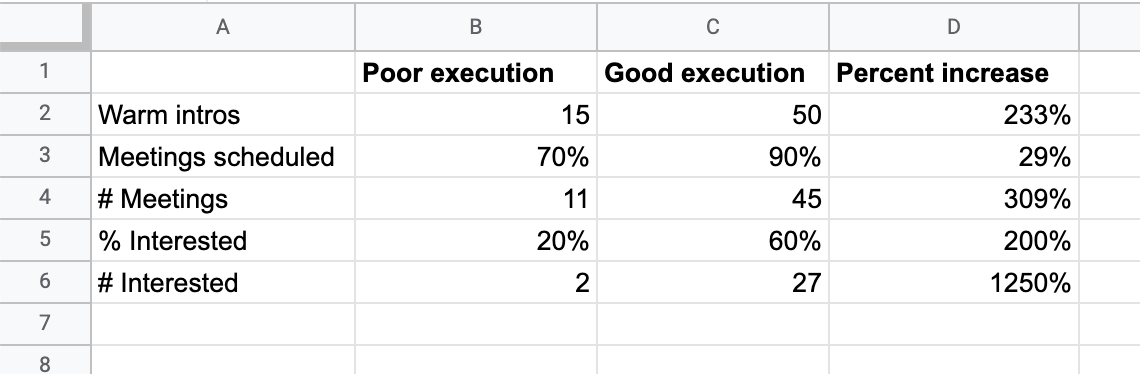

Moving from 15 to 50 intros is a huge deal on its own (233% improvement), but let’s remember this is just one tiny step in a larger fundraising process, and the fundraise itself is a tiny part in the larger company building effort. Now imagine a team finds a way to do all the other parts of fundraising (honing the narrative, crafting a solid deck, running an efficient process, etc) at just as high a level of quality—obviously the high-execution team is going to end up with a much better fundraise, which puts them in a better position to do everything else.

This compounding effect of many steps performed at a high level together is so much bigger than a single point of improvement. It’s easy to underestimate the effect, which is why I’ve created a simple mathematical model to illustrate it. We’re going to see how far we can extend the fundraising example above, but the idea is that similar mathematical analysis could apply to literally any business process: marketing, sales, product development, recruiting, user onboarding, etc.

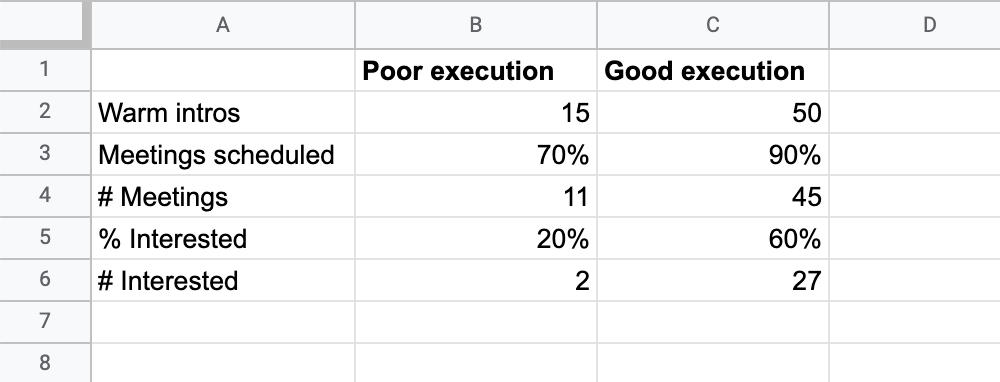

In this model, there are two modes: “bad execution” and “good execution.”

To start we’re taking the estimated 15 warm intros that bad execution yields, and 50 warm intros that good execution yields. The next steps are: get a meeting on the books, and keep following up until you sort each investor into either “interested” or “not”. (We’ll cover the rest of the fundraising process next.)

Even with poor execution, I bet most founders can convert 70% of the warm intros they receive into meetings, but there is an art to following-up and pitching your startup in an attractive way, as well as the art of selecting which investors to pitch in the first place, so I think with good execution you can get 90% conversion rate to a meeting. That leaves 11 meetings with poor execution, and 45 meetings for the team with good execution.

But of course having a meeting is not the same as attracting real interest. Good execution will achieve this at much higher rates than poor execution. I can’t go through all the complex litany of skills and experiences required to show up in a pitch meeting and leave an investor wanting to invest, but let’s say that poor execution (within the context of an otherwise interesting business) leaves 20% of investors interested. Good execution of the pitch meeting for that same business might convince as many as 60% of investors.*

(*Note: if this seems unrealistically high to you, ask yourself whether you’ve ever encountered a truly gifted salesperson. These people might be mocked as frauds or manipulators, but often they’re just exceptional communicators with a high degree of personal charisma. Also remember that this model assumes the “good execution” company did a better job of identifying investors who were already interested in their thesis and had made similar investments. If anything, I bet 60% is a low conversion rate for founders of companies that become “hot deals.”)

At the end of this process, based on execution alone, one company has 2 interested investors and the other has 27. Obviously the latter company is going to be able to raise more money on better terms from higher-quality investors.

But the most important thing to learn from this is the math of compounding good execution. The process we described had three steps: get warm intros, convert them into meetings, and convert meetings into interested investors. Good execution of each step individually yielded results that were 2-3x better than poor execution. But each step doesn’t happen in isolation, and by the end the compounding effect led to a 12.5x improvement in outcome—an exponential improvement if I’ve ever seen one!

Now imagine a zoomed-out version of this math that covers everything a company does. Imagine how the increased interest from investors flows into increased cash, increased ownership, increased hype, and increased talent recruiting. Now imagine how all that flows into product improvements, and how product improvements flow into improved revenue and retention metrics, and so on. It’s just one giant loop, and every step in the chain can make a difference.

Furthermore, good execution in one area tends to lead to good execution in other areas of the business, because good execution is only possible within a culture that permits (and even demands) excellence. Good execution leads to increased morale. The bar for everyone gets raised. The energy of good execution is contagious.

I think the hardest part about good execution is that it’s not the same as just trying harder. There is only so much time in the day and so much effort that is possible. You can work yourself to the bone but that might actually make your execution worse in many ways. My perspective is that good execution mostly comes from experience and skill, not from simply trying harder. This is why investors often bias towards people that have worked in hyper-growth startups in the past. If you don’t know what “good” looks like, you will have a hard time replicating it and might prematurely conclude you have a bad plan when actually you just didn’t execute it well enough.

And what should you do if you haven’t worked in a hyper-growth environment? I have a few tangible suggestions.

First, don’t assume you’re currently operating at 80% efficiency. It’s quite possible you could string together a series of 10x wins in many parts of the business—especially if it’s a skill or activity that is new to you.

Second, prioritize and focus. Think of your business like an equation, and study each step in the process to see which you think could be most improved and would have the biggest impact if improved. For example, with Every right now I think the single biggest thing I can do is just to write better. It’s tempting to think my writing is already pretty great and we should try to promote it better, but I’ve written enough bangers in the past to know the biggest impact is just quality. If a piece doesn’t get a ton of positive feedback, it just wasn’t that great. And that’s ok! It’s freeing (and necessary) to be able to admit this to yourself, be okay with it, and move on.

Third, try to figure out how others are doing it. Don’t listen to what they say, pay attention to what they do. Go through their onboarding process. Book a call with their sales team. Talk to their former marketer. Remember, God is in the details and you should be obsessed with what is working in your space at the moment.

Fourth, manage your own energy. It seems like once a year people on Twitter get mad when someone says they have to work hard in order to do extraordinary things, but to me it just seems uncontroversially true. If you look at the fundraising example above, it’s clear that the “good execution” version took a lot more time and energy than the “poor execution” version. That’s why I’m personally more focused on diet and sleep and physical fitness than ever before. I realized I need the energy I get from those activities to actually perform my best in my writing. But you should do whatever works for you.

Do you have tips for improving execution? Any thoughts for me about the ideas in this post? I would love to hear about it! Just click one of the feedback buttons below.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Amateurs talk strategy; professionals talk logistics.