Usually in business things go worse than expected. But every once in a while, if you’re lucky, an experiment goes 800% better than you hoped. And when it does, you’d better understand it.

Sooooo... this week I’m writing about bundle economics 🙃

...

Four months ago my friend Dan and I decided to start paid newsletters together. They’re independent businesses, but we operate like a team. We edit each other’s pieces, share all our data, and brainstorm growth ideas together.

One idea we came up with recently was to offer a bundled version of our newsletters. The theory was based on an idea called “bundle economics” that I thought might apply in our case. So, this past Monday, we launched the bundle.

The night before launch we talked on the phone to guess how many subscribers this bundle experiment might bring in. To put it in context: in the past, we might get 5-10 new subscribers on a good day, and 15-20 new subscribers on a great day. On the night before we launched the bundle, we had 648 total subscribers between the two of us.

Dan and I were both really excited about it, and thought it might be one of our best days, so we predicted we’d get 20 new subscribers from the bundle. In retrospect, it’s kind of embarrassing how wrong we were 😆

In the three days since we launched the bundle, we added 180 new subscribers, bringing our collective total to 828. That’s exactly 800% better than the 20 we had hoped for. Overall, we had 28% subscriber growth in just a few days!

One other cool thing — 274 (40%) of our existing subscribers opted in to the bundle, so we each increased the audience for our paid posts by quite a bit.

...

It’s not obvious why bundling is good. And in fact, bundles are often bad! Sometimes you should unbundle. It entirely depends on the circumstances.

The unbundler says, “Right now your only option is to buy ABCD, but you really just want B. So I’m going to sell B to you as a standalone, for a lower price.”

Substack exemplifies this. They enable writers to say, “Hey, I think you really just want my work, instead of some newsletter I could be a part of. So here’s a way to subscribe to me directly.” Another great example was iTunes, which let you buy individual songs, back when people had to buy CDs.

On the flip side, the bundler says, “Hey, right now you have to buy A, B, C, and D separately, but you’d like them all. So how about I sell you ABCD in one convenient package, for a lower price?”

Spotify exemplifies this. They enable listeners to get access to almost every song ever recorded for $9.99 per month. This is an amazing deal compared to when we had to pay $12 or more for a single album. Another great example was cable TV, back when people did that.

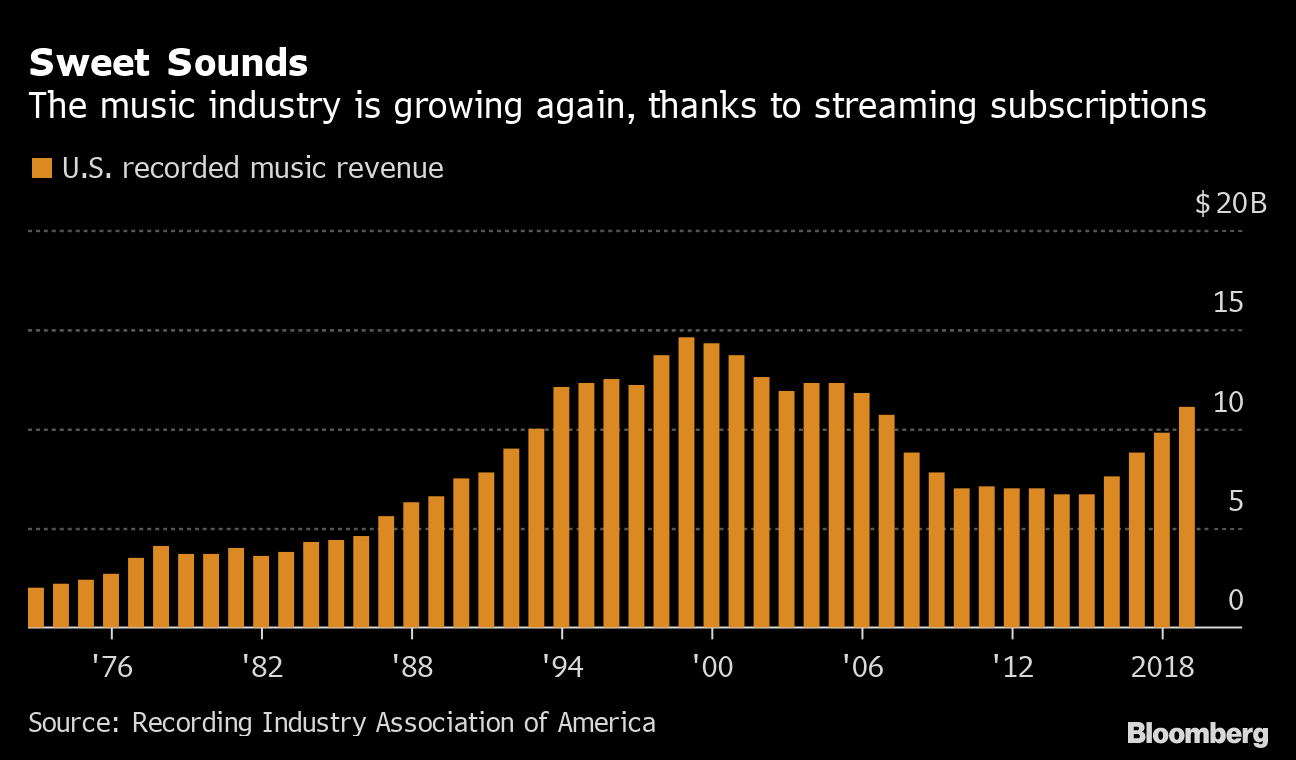

You’d think that this would be bad for the music industry as a whole, right? They used to charge $10 per album and now they charge $10 per month. They must make less money?

Wrong. They’re actually on track to make more money now that they’re bundling. Just look at this graph:

(source)

How does that work, though? How can they make more money by bundling a bunch of products together and selling them for less than the sum of the parts? (Sometimes — as in the case of Spotify — for far less!)

Unbundling is kind of obvious (you want less stuff, so you pay less money), but there is a sort of dark magic inherent in bundling, which allows it to benefit both buyers and sellers in wonderful ways.

Dear reader, I am here to explain the dark magic to you 😈

...

It goes something like this:

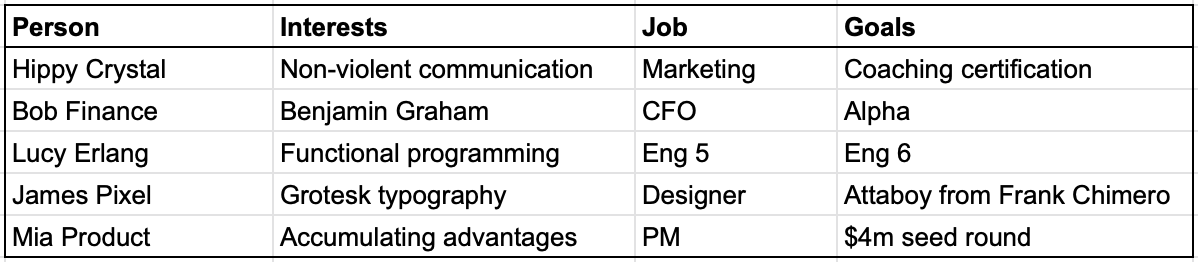

Imagine a group of five friends.

They’re all different, but they have a lot in common. They all work in tech, they’re ambitious, and they love to read.

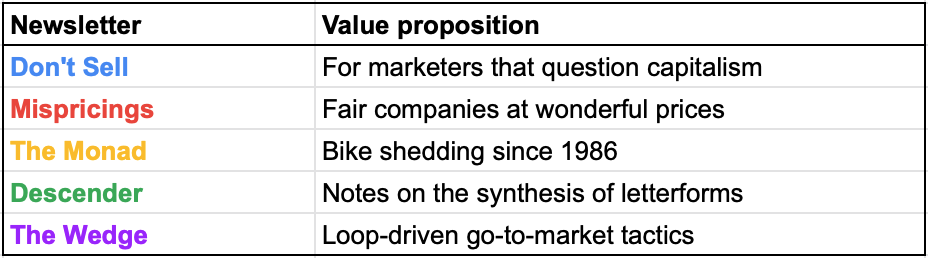

Now, imagine these friends are presented with five email newsletters:

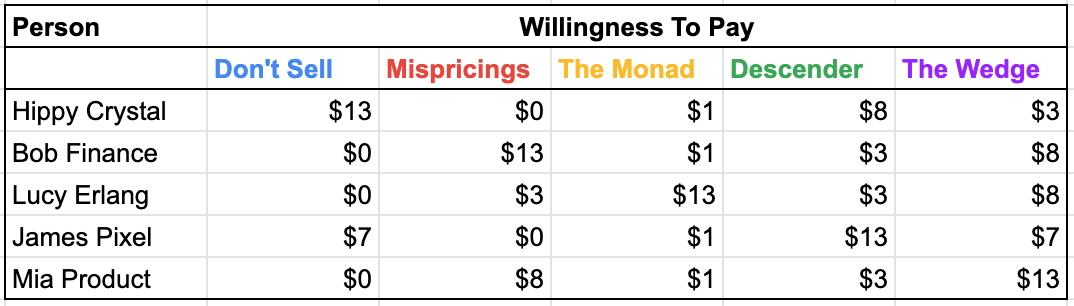

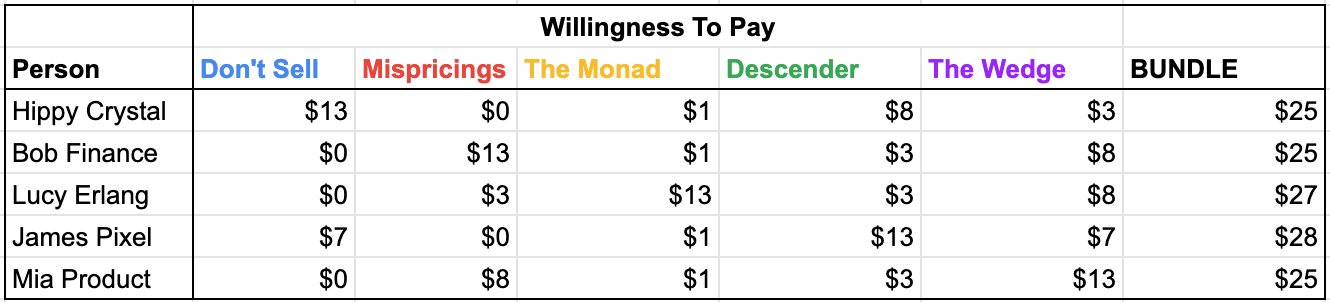

Because they’re different people, they all have different willingness to pay for each of the newsletters.

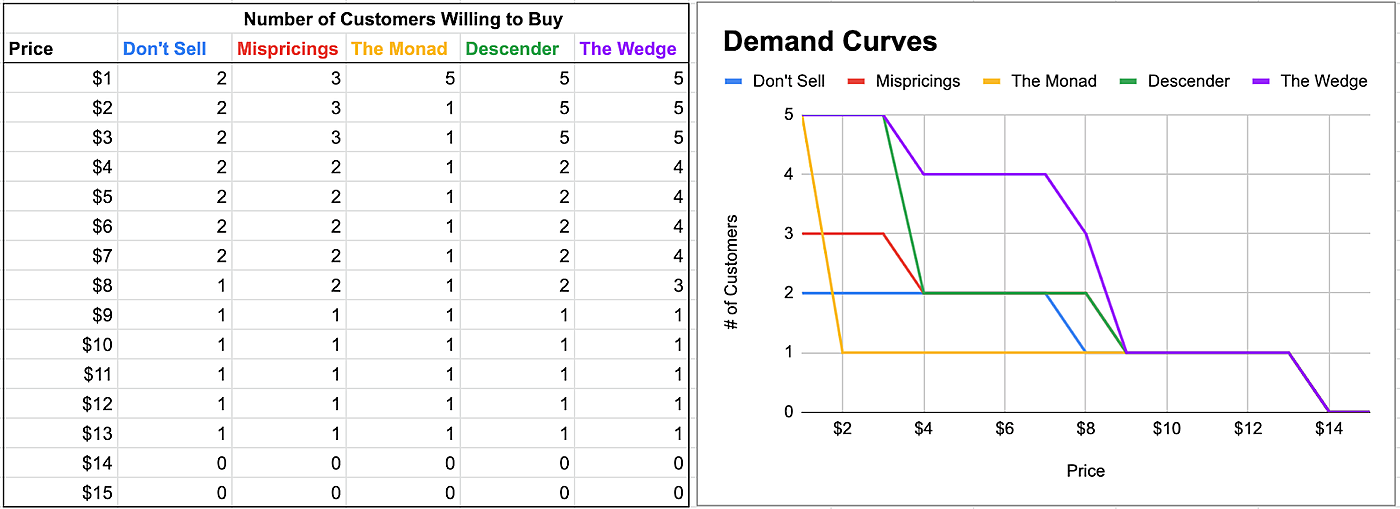

Given this data, we can make a graph showing how many people would pay at any given price for each newsletter.

In other words, a demand curve:

The demand curves slope down, just like they do in Econ 101, because the higher the price, the fewer people will buy it. For example, if The Wedge charged $9, only Mia Product would pay for it, but if it charged $3 or less everyone would buy.

From this, we can find the price each newsletter should charge in order to make the most money:

The highlighted numbers are the highest possible revenue each newsletter can make from this group of friends. To the left in the “price” column is the amount they should charge to earn that much revenue.

Most newsletters should charge $7-8, and capture the top two most interested readers, while sacrificing the bottom three. The exception is The Monad, which is super niche and should charge $13. Lucy Erlang is the only one who wants it and that’s how much she’s willing to pay.

(Note that Lucy’s willingness to pay for The Monad is not higher than her friends’ willingness to pay for their favorite newsletters. This is a common misconception of why niche products often charge more. It’s not necessarily that their users are willing to pay more, it’s that they have less to lose by charging a higher price.)

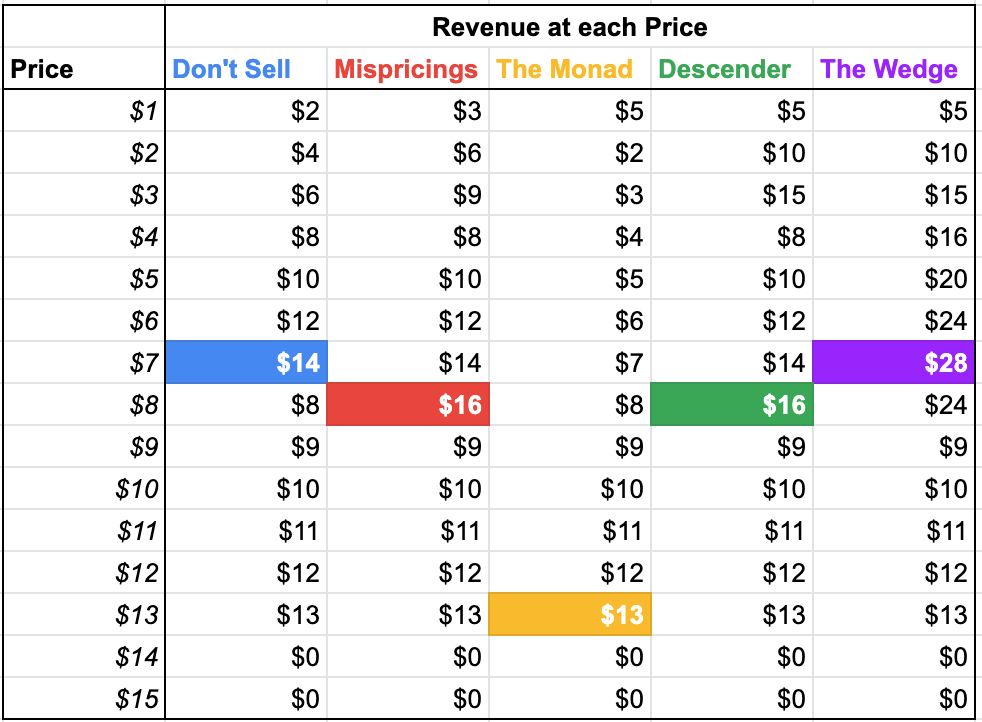

Ok, so, how much money can these newsletters make on their own? And how much access can they generate?

If you add up the maximum revenue for each newsletter above (the highlighted numbers), you get $87 in total revenue, at a cost to consumers of $43 total to buy a subscription to each one.

Can we do better with a bundle? Yes we can.

By selling all newsletters together as a bundle, they can make a total of $125 — a 43% increase over the $87 they could make separately! And it’s not just about squeezing money out of people. The revenue-maximizing price for the bundle is just $25. That’s 41% cheaper than what it would cost to buy each newsletter individually!

What??? Magic. Allow me to explain.

The thing that makes bundles work is they eliminate waste. What waste? The wasted demand of all the people who want access to each newsletter a little bit, but not enough to pay the market price.

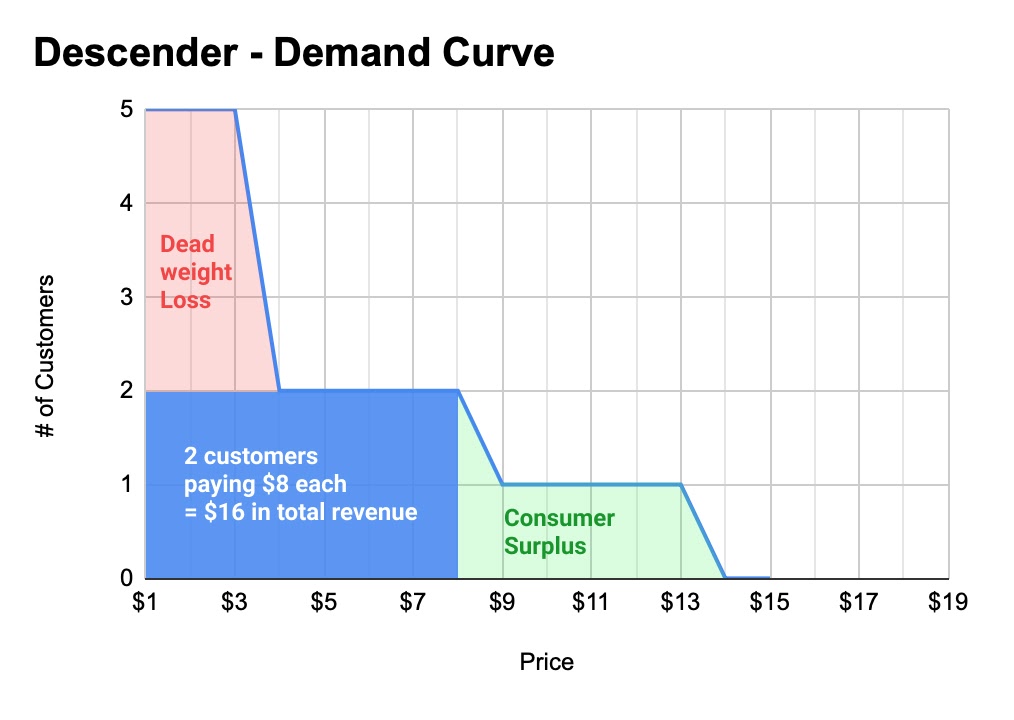

For example, the best price for Descender is $8. But only two people are willing to pay it, meaning they are capped at $16 in total revenue. The other three friends are willing to pay $3 each for Descender, but they end up paying nothing. So there is $9 wasted. That’s called “deadweight loss.”

You can see it represented visually on the demand curve in red below. Basically, three people would have paid $3 but didn’t.

The other thing to notice is that one person, James Pixel, was willing to pay as much as $13 for Descender, but he only had to pay $8. So that’s called “consumer surplus”.

Consumer surplus is nice because it means people feel like they’re getting a good deal, so maybe they’re more likely to stick around or tell friends. But deadweight loss is good for nothing. Readers don’t get the content they want, and writers don’t get the audience and money they want.

We want to do everything we can to reduce deadweight loss.

So, how do you do that? One way is to price discriminate. This happens in a lot of settings, like Fortune 500 boardrooms and Indonesian night markets, where you can glean information about your buyer and can offer a discount or charge a premium when it seems called for. That’s one way the blue box above can expand to fill more of the area under the demand curve. Haggling works!

But, custom pricing is not always possible. Spotify doesn’t have time to negotiate with you. In those cases, bundles can be a great way to solve this problem. By offering a bundle instead of an individual purchase, you change the shape of the demand curve in such a way that it’s flatter, and there is less deadweight loss.

Let’s show this in action.

First, we’ll create a new column on the right that represents how much each person would be willing to pay for a bundle that includes all five newsletters.

It’s pretty easy to construct, you just add up their willingness to pay for each individual newsletter:

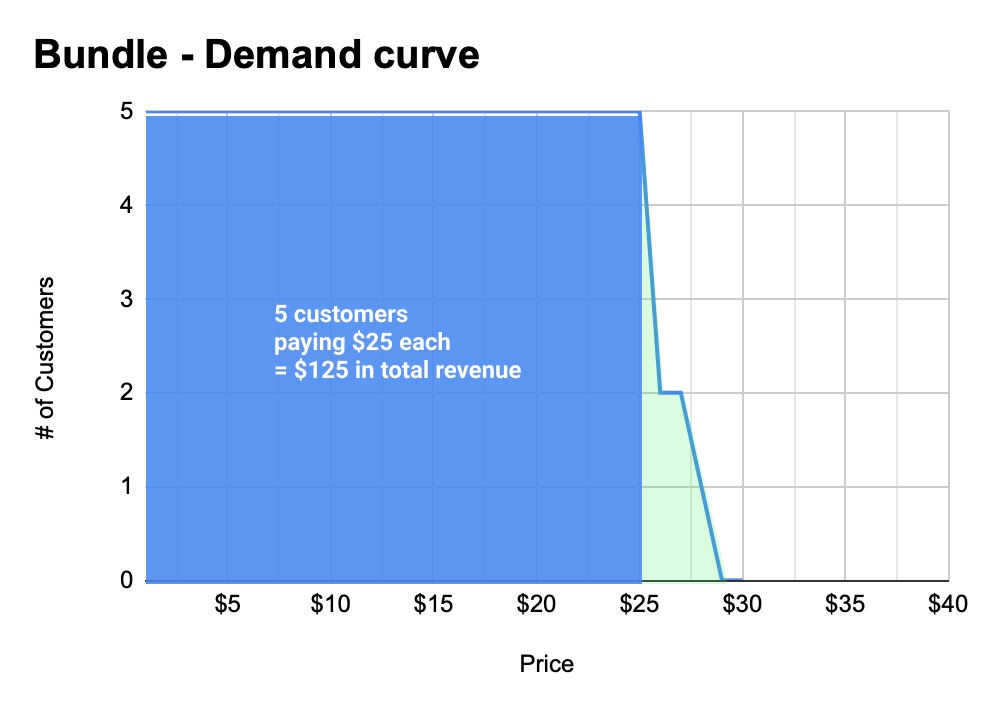

Now we can plot this and see what the demand curve for the bundle looks like.

The deadweight loss is... gone!

This is how the bundle can earn $125 when the individual newsletters could only earn $87 in total. The demand curve is flatter, so there is less space up top in the “deadweight loss” zone. (In this particular example, none!)

It works because even though each person valued each newsletter differently, everyone was willing to pay at least $25 for access to all 5 newsletters. And, importantly, that demand had far less variance than the demand for individual publications.

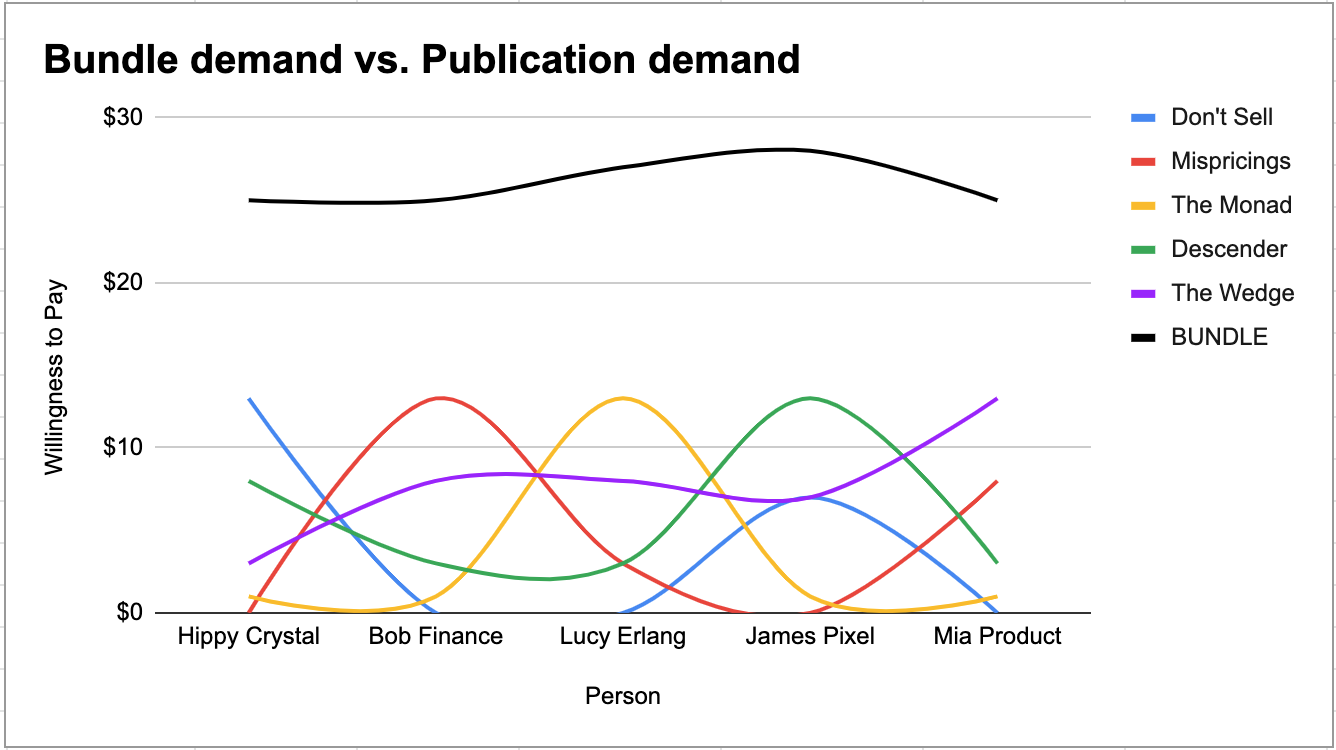

Here’s a one way to visualize the decrease in variance. It’s a graph of demand for the bundle (the black line on top) compared to demand for individual publications, across each person.

Notice how smooth the bundle’s curve is? It’s lovely.

The less variance, the easier it is to charge a price that works for everybody, the less deadweight loss you have.

It’s great!

...

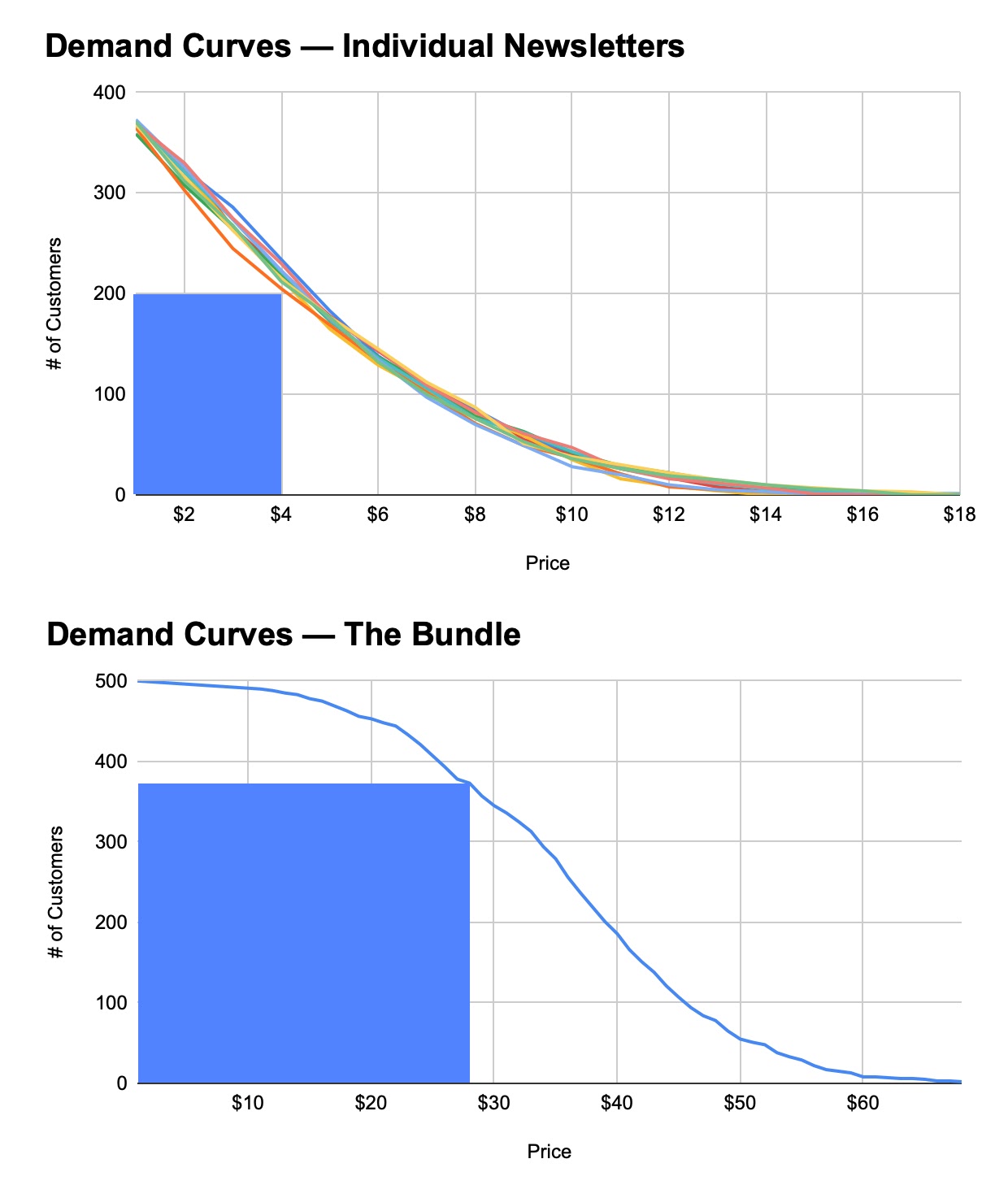

Of course, this is an extremely simplified example. We’re looking at a world of five consumers and five publications. We managed to achieve zero deadweight loss. It made me wonder: what happens if we scale it up to something slightly more realistic?

To test it, I created a spreadsheet with 500 consumers and 10 publications, using random numbers meant to simulate “willingness to pay.”

(In case you want to try it yourself, the Google Sheets formula I used to simulate demand was “=IF(RAND() > 0.2, ABS(ROUND(NORMINV(RAND(), 0, 5), 0) - 3), 0)”. Don’t worry about reading that code if you don’t want to. You can just look at the graphs below to see what kind of numbers it spits out.)

Here’s a graph of the demand curve for the individual publications, as well as the demand curve for the bundle:

In this simulation, the optimal bundle price was $28 and 373 out of 500 would buy it, yielding $10.4k in revenue. Individual publications sold separately yielded $8.5k in total revenue. So, even in an example that’s more realistic, you still make 18% more money by bundling!

...

In all the simulations I ran, the bundle tended to perform anywhere from 10% to 50% better than the non-bundled option. I thought this was pretty cool, but it made me wonder what determined the difference? Why did some trials perform so much better than others?

To test it, I ran a little experiment. I tested out five different versions of my “demand simulator” (that crazy google sheets function I showed you earlier).

The key variable I tested was the probability that a user’s demand for any particular newsletter was zero. Let’s call it p(0). If the p(0) was high, then it simulated a world where most people really just wanted one newsletter and didn’t care much about the rest. If p(0) was low, it meant everyone wanted every newsletter, but they wanted them different amounts.

I ran 10 trials with each of my five algorithms, then averaged the results. This is what I got:

This chart is actually crazy — it shows why sometimes a bundle is actually a bad idea.

See the right side of the graph, where the line dips into negative territory? That means you would have made more money had you offered each newsletter individually.

The relationship here is very clear: if people have zero demand for most things in your bundle, it’s a bad idea to try and force a bundle on them. But if people have a little demand for everything, and a lot of demand for some things, then a bundle is a great idea.

If you think about it, it makes perfect sense.

Remember what the unbundler said, at the beginning of this essay?

“Right now your only option is to buy ABCD, but you really just want B. So I’m going to sell B to you as a standalone, for a lower price.”

This chart proves that it can work — mathematically!

And the same goes for the thing the bundler said:

“Hey, right now you have to buy A, B, C, and D separately, but you’d like them all. So how about I sell you ABCD in one convenient package, for a lower price?”

It all makes sense now.

...

Of course, in the real world our demand isn’t a fixed number in a spreadsheet. It’s more slippery than that. It depends on our mood, and the exact context we see it in, and how handy our credit card is, and whether we’ve recently eaten.

There are also information costs to figuring out how much we even want something. That’s one reason you don’t often see bundles with lots of disparate goods — it would take too much work to explain what’s in there! It makes a lot more sense when everything fits a certain intuitive pattern, like songs (Spotify), movies (Netflix), and sports news (The Athletic). That way customers just “get it” and can make a judgment call on how much it’s worth to them without spending a lot of time researching what’s included.

Lastly, none of the analysis above works for physical products, or consulting services. It only makes sense to give people things they don’t fully want if it costs you nothing to give it to them. So it works for software and digital media, but not much else. This is why music and movies weren’t previously offered as a bundle when they had to be printed on discs and shipped, but now that they’re delivered for essentially free over the internet, they’re bundled.

But, overall, despite all these complications, it felt pretty damn good to see a hunch turn out to be true in a way that was bigger than I could have ever hoped for. It gives me confidence that all this time spent reading dense textbooks and playing around in spreadsheets is worth it.

The default “willingness to pay” for writing on the internet is zero, and it takes something special to dislodge it from that spot. So it means the world to Dan and I that so many of you decided our writing was worth paying for. Because of this week’s success, we’re pretty much ramen profitable. That means we can do this indefinitely, and start re-investing resources to make it as valuable as possible for you. We’ve got a ton of ideas we can’t wait to share with you.

In the meantime, thank you so much for betting on us. We promise to never take that for granted, and to never phone it in.

With that, thank you for the amazing week, and see you soon!

—Nathan

PS — if you’re interested in seeing the Google Sheet I used to run these numbers, it will be available to paying subscribers within the day, along with the audio edition of this essay.

Was this helpful?

Please train my “neural net” and click the purple “Like & Comment” button at the bottom!

(This is no vanity exercise—the only purpose it serves is to create a feedback loop for me, so I can make Divinations better for you!)

Divinations is proudly reader-supported. Join us.

Subscribers get access to a podcast feed with audio editions of each article, and access to the ever-growing library on explainers on the most important ideas in strategy, including:

- How Competition Works— Why markets are like ecosystems, and why that means you should “compete to be unique,” rather than “compete to be the best.”

- Your Actual Competition— Michael Porter’s “five forces” framework is one of the most useful and enduring ideas in business. Here’s the Divinations explainer of it.

- Trade-offs Are Your Friend— How to use trade-offs to prevent competitors from copying you, and about how to know when you should (and shouldn’t) copy your competitors.

There are two purchasing options. One is to buy Divinations for a stand-alone price of $13 a month, but the new option, as you certainly are aware if you’ve read to this point, is the bundle where you get access to this and Superorganizers!

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Really enjoyed this post - thank you! One question though. You say "if people have zero demand for most things in your bundle, it’s a bad idea to try and force a bundle on them". While Spotify and Netflix provide one type of good, their users arguably have zero demand for most things in the bundle. How do you square this with the earlier statement?