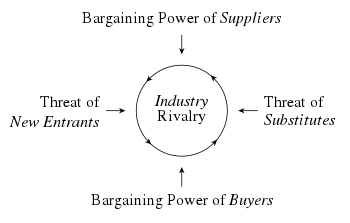

Your business has more competition than you may realize.

When most people list their competitors, they usually just name companies that make similar products. But in reality, they should also think of their suppliers, customers, substitute products—even potential new entrants that don’t exist yet!—as competitors.

Of course, these relationships are collaborative and beneficial to everyone involved. But it’s important to realize that they are competitors, in the sense that they compete with you for profit.

It’s like a 360° tug of war:

- Industry rivals compete to offer higher value and/or lower prices (e.g. Ford vs Chevy).

- Buyers want the most value at the lowest price. If they can find a better deal elsewhere, they’re happily switch (e.g. some random widget manufacturer vs Wal-Mart).

- Suppliers want to charge you as high a price possible, and make it as hard as possible for you to switch (e.g. Dell vs Intel).

- Substitutes are ready to cannibalize your industry by picking off segments of buyers and serving them in totally unique ways that make your product irrelevant (e.g. The New York Times vs Twitter).

- Potential entrants are waiting in the wings, ready to swoop in if they sense they could succeed by offering buyers a better deal (e.g. Divinations vs other smart business thinkers who don’t currently have a newsletter but just know they could make something so much more compelling than this).

This idea—that there are five forces that influence your profitability—is what launched Michael Porter’s career. In 1979, he published “How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy” in the Harvard Business Review. It was an instant classic.

It may seem like a simple idea, but the implications are wide-ranging.

For example, it might seem like a business’s profitability depends mainly on competitive pressure from rivals—but the other four forces have a huge collective impact. And since all companies within the industry are subject to those same pressures, there is a baseline level of profitability that varies from industry to industry.

In other words: some industries are consistently more profitable than others. This explains the economic logic behind the famous Warren Buffet quote:

“When a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact.”

Using the Five Forces

Whether you’re an entrepreneur, executive, or investor, if you want to understand a business, it’s incredibly helpful to run a “five forces analysis.”

To start, research and answer the following questions:

-

What are the barriers to entry?

- Are there economies of scale? Network effects? Patents? Etc.

- How hard is it for buyers to switch?

- How much capital would it take to start a competitor?

- Are there any scarce resources you have access to that competitors don’t?

- How likely are existing players to try to drive new entrants out of the market?

-

What’s the bargaining power of suppliers?

- What are your costs of goods sold?

- How might that change as the business scales?

- If any of your suppliers doubled or tripled their price, how easy would it be to replace them? How badly would it impact your profitability if you stayed with them?

- How much do your suppliers depend on you to stay in business?

-

What’s the bargaining power of buyers?

- What percent of your total revenue do your top 10 customers account for?

- How easily can your buyers switch to your competitors’ products?

- Do your buyers demand high quality and are willing to pay a premium? Or are they price sensitive?

- How much of your buyers’ cost structure do you make up? (The higher % of their costs are attributed to you, the more it’s worth it to them to bargain.)

-

What’s the threat of substitutes?

- Before people started using your product, what did people do?

- When people stop using your product, what do they do instead?

- What other categories of products serve the same “job to be done” your product serves?

- Are any of your substitutes steadily getting better? Cheaper? Both?

- How hard would it be for your customers to switch to the substitute product?

-

How competitive are existing players?

- Are there a lot of competitors?

- Are most businesses roughly of the same size / market power?

- Do you compete on price? Or on differentiated value propositions?

- Do players in your industry have high fixed costs and low marginal costs? (If so, price cutting is more likely.)

- Can you scale smoothly, or only in large increments? (If in large increments, expect fierce competition to make big investments in extra capacity pay off.)

- Is the industry growing? How quickly? (If not, expect tougher competition to claim an increased share of a fixed pie.)

Then, once you start to get a rough sketch of how each force affects your business, you can generate a list of experiments to run, or questions to dive deeper on.

The list of questions above isn’t exhaustive. As you spend time answering them, you’ll think of others. The main idea is to figure out how things work.

Going through the process helps you build a much better model of your industry in your head. You’ll notice hidden opportunities and threats. Your current strategy will become more clear, and you’ll come up with lots of ideas for experiments and tweaks to your model.

Some of these ideas could turn into actions that transform your business.

An example: Spotify

The story of Spotify makes a powerful “five forces” case study, because it illustrates how entire corporate strategies are often designed to combat one powerful force.

(It’s also fascinating to me, personally! I used to work at Gimlet Media, which was acquired by Spotify for reasons that will become apparent below.)

Let’s quickly go through each of the forces:

Potential entrants: weak

It’s pretty hard to launch a new streaming music service. (Just ask Tidal.) First, you have to get the attention of record labels and negotiate a deal with them. That’s going to take years.

Then, you have to build a good product experience. Even to hit a baseline level of quality, it’s going to require a pretty huge amount of solid engineering and design time and talent. (Many would argue even Apple Music isn’t as good of an experience as Spotify!) You’re also going to have to integrate with a lot of devices—phone operating systems, cars, smart speakers, smart TVs, gaming consoles, and maybe a refrigerator or two.

Then, even if you manage to do that, you have to convince people to switch.

The market for streaming music is relatively mature. It’s going to be hard to find people who are A) willing to adopt your new streaming service, but B) haven’t adopted one yet, for whatever reason. So in all likelihood, you’re going to have to convince people to switch away from Spotify. The force of habit is strong, and people have a lot of history with Spotify, which gives them the ability to deliver personalized recommendations.

And then once you’ve done all that, you’re entering into a business that is really hard to turn a profit in (for reasons we’ll explore below). So it’s not likely that startups or incumbents will attack Spotify head-on. Perhaps we’ll see other businesses use music to subsidize something else (for instance, Amazon Prime), but few businesses have a large enough cash cow to make it worth it to compete in music streaming.

So the threat of new entrants is relatively weak.

Industry rivals: medium

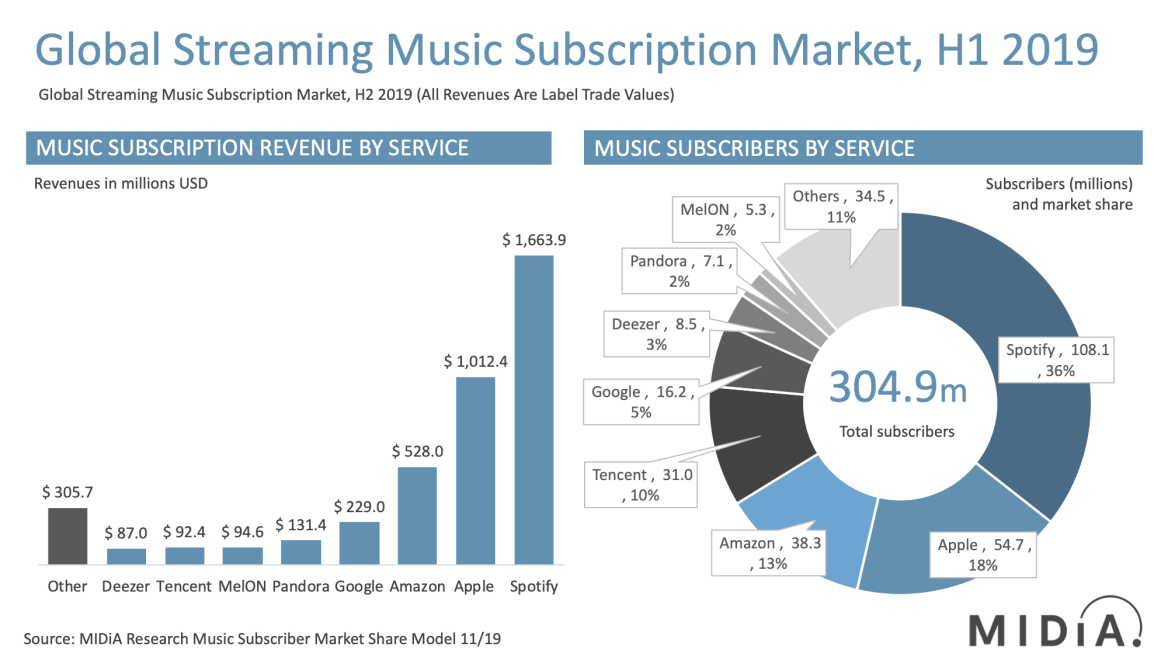

Spotify is the number one subscription service for streaming music, with double the subscribers as Apple Music, which is in second place.

So far the competition has mostly centered around three variables:

- Catalog selection - do you have deals with all the major record labels, as well as indie and obscure artists? Spotify is in the lead globally on this, although regional players like Tencent, Deezer, and Melon have advantages locally.

- Price - how much do monthly subscriptions cost? Are there ad-supported tiers?

- User experience - are you available on all platforms? Is the app fast and easy to use? Do you have good curation and discovery?

The streaming industry is growing, so competition hasn’t centered primarily on price, which is good for profits. Also, there’s not much room to lower the price, because the costs of streaming royalties are so high. (More on that below.)

The wildcard, as usual, is Amazon. Unlike almost everyone else, they’re not primarily in this business as a profit center. They have a $7.99/mo service for Prime members that undercuts Spotify and Apple’s $9.99/mo offering. The goal here, as with their Prime Video, is to get people to sign up for Prime and buy more stuff on Amazon, not to make money off music streaming.

Substitutes: strong

Spotify faces significant pressure from free and cheap alternatives.

It’s always hard to draw the line between “substitutes” and “competitors.” Here, I’ve decided to count Pandora’s comparable streaming service as a competitor, but their “internet radio” offering as a substitute. Pandora is also now owned by another internet radio company: SiriusXM. Internet radio subscriptions are about half the price of Spotify and Apple Music, because they pay less in licensing fees.

And of course, there’s always regular old FM radio, which is free. 272 million people in the US listen to it every week.

There’s also YouTube, which tons of people use to listen to music for free.

So the threat of substitutes is relatively strong.

Buyers: weak

Spotify’s sells to individual consumers. So they’re extremely fragmented and can’t bargain as a bloc. This would indicate relatively weak bargaining power.

But the switching costs are pretty low. If Spotify doubled their price, you can bet that Apple Music, Amazon, and Google would have a flood of new customers. So in that sense, buyers have a decent amount of power—the power to switch.

Here are some ways Spotify is working to mitigate this:

- Exclusive content you can’t get anywhere else (both music and podcasts—hi Gimlet!)

- Branded playlists that become cultural focal points (e.g. RapCaviar)

- Personalized discovery (see the “Your Daily Mix” playlists)

Suppliers: sicko mode

This is the big one.

Three companies—Universal, Sony, and Warner—own about 80% of the music business. And they’re very effective at using their clout to extract profits from Spotify and artists.

Here’s how the economics work. For every $1 of streaming revenue:

- Artists, songwriters, and publishers get ~30¢

- Spotify gets ~30¢

- Record labels get ~40¢

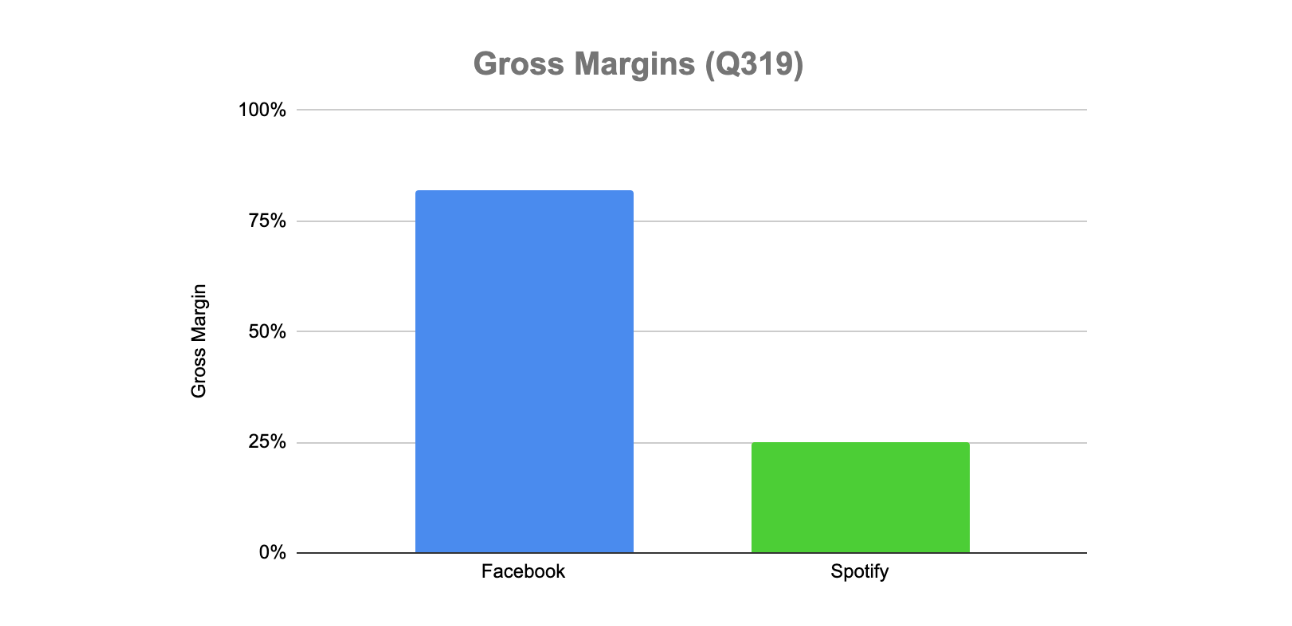

You can see it in Spotify’s financial statements quite clearly. It’s under the “cost of revenue” section. In Q3 2019 (the last quarter for which we have data), Spotify took in €1.7 billion euro in revenue, and spent €1.2 billion on royalties, hosting, etc.

That leaves them with a 25% gross margin—which doesn’t include spending on sales and marketing, G&A, product development, or acquisitions like Gimlet and Anchor!

How bad is that? Pretty bad. Especially for an internet business.

Let’s compare that to a different business facing extremely weak “bargaining power of suppliers” — Facebook. In Q3 2019, Facebook took in $17.6 billion in revenue, and only spent $3.1 billion in direct costs (mostly web hosting), leaving them with a gross margin of 82%.

This leaves Spotify with comparatively little money left over to reinvest in marketing and product development, which makes it harder for them to grow.

So, how do they solve the problem? Two ways:

The first is to go around the record labels, and work directly with artists. This is a strategy they’re dabbling with, but cautiously.

Even if Spotify could get new artists to skip the traditional record deal, they’d still need to work with the labels to keep the back catalog in their app. (In music, the back catalog is uniquely valuable.)

How do you think those labels might react if Spotify tried aggressively to go around them? It wouldn’t be pretty. So they have to be extremely careful.

This leads us to the second strategy for coping with record label’s power: podcasts.

Unlike music, the back catalog isn’t that important. And more importantly, the content isn’t controlled by an oligopoly of three huge companies. It’s owned mostly by creators, with the exception of a few big networks, like NPR, Gimlet, and Wondery. Even better, it’s available for free.

Every minute Spotify users spend listening to podcasts is a minute that Spotify is getting user engagement (and therefore less likelihood of churn) without having to pay the labels. So it makes complete sense that Spotify would want their users to start listening to podcasts in addition to music.

It’s also much easier to offer exclusive podcast content, because there’s not the risk of angering record labels. This is why Spotify bought Gimlet, and presumably why they bought Anchor (a free podcast production tool integrated with a hosting platform).

So far, Spotify’s moves into podcasting seem to be working incredibly well relative to the (traditionally tiny) podcast industry, but there are no signs that their strategy is resulting in increased gross margins yet.

It’ll take time to pay off.

fin!

Next week, I’ll cover the final big concept from Porter (his three generic strategies) and then transition into a few weeks of case studies. They’ll feel like the Gimlet example above, but a bit longer, and incorporate all of Porter’s frameworks. If you have any specific companies you’d like me to focus on, let me know!

As always, I really appreciate any feedback or questions you have, and will be hanging out in the comments. And please hit the “like” button if you thought this was a good one! (It helps me learn what you like.)

Thanks so much and see you next week!

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!