Want to listen to this post instead of reading it? Click here.

This was written by Adam Keesling, and edited by Nathan Baschez.

Do you remember how you listened to music twenty years ago?

Me neither, I was four years old. But let me paint you a picture based on second-hand accounts.

Start at your desktop computer.

Dial-up your internet and open Napster.

Search through the songs. Once you’ve found your jam, find the file that looks the most legit and click download.

Wait a few moments for it to download. Then wait a few more.

Alright now hop over to Windows Media Player, insert a CD into your tower, and burn the songs onto the disk.

Pop it out, then pop it into the CD drive of your home stereo system.

Hopefully you already spent a long weekend lugging around subwoofers, drilling holes in your walls, and untangling the mess of cords.

If not, now would be a good time to start.

Then — finally — plop down on your couch and enjoy the beautiful 5.1 surround sound piping through the air.

Safe to say things are a bit different in 2020.

…

There were several companies that were instrumental in building the audio ecosystem into what it is today, and Sonos was certainly one of them.

Lucky for us, Sonos is also an interesting case study in business strategy.

Their story can be told through the lens of The Conservation of Attractive Profits, an idea Clay Christensen introduced in his book The Innovator’s Solution.

The idea is simple: a business has a competitive advantage when it controls the thing that customers care about that isn’t good enough. When that happens, all adjacent businesses tend to adapt themselves to fit the standard defined by the company that controls the critical piece.

For example, in the 1990's, computer hardware manufacturers had to adapt to what Intel wanted, because Intel controlled the CPU, and the CPU determined speed, which was what customers cared about most.

From Christensen:

The companies that are positioned at a spot in a value chain where performance is not yet good enough will capture the profit.

In the 2000s, Sonos controlled the most important thing in the home audio market. At the time, the incumbents were traditional audio companies such as Sony and JBL. However, there were two things that made performance not good enough:

- In order to have high-quality audio in your house, you needed a wired setup. This was not only time-consuming to set up, but also was constrained to a single room.

- There was no easy way to play MP3's from your computer (let alone from a remote) to your home sound system, which was built for CDs.

These problems sparked Sonos to build the first high-quality wireless home speaker system. For the first time, it was easy to set up whole-home audio systems, and stream MP3s from iTunes. The plan worked and they rode this innovation to success.

But what's most interesting about Sonos is not how they got their initial traction. It's what happened next. Their true legacy is defined by how they responded to change as their market evolved. Or rather, how they didn't respond.

In this post, we’re going to examine Sonos’ strategic decisions, many of which were at the crossroads of major audio trends:

- Positioning as high quality (and high price)

- The proliferation of headphones

- Voice assistants and smart speakers

- Committing to a hardware business model

Which brings us to today. Does Sonos have a competitive advantage? Or are they like most consumer hardware products which devolve into modular commodities?

Let’s dive in to figure it out.

Sonos’ Founding Vision

From their experience building Software.com (a wireless internet company with an amusingly generic name), the four Sonos co-founders saw an opportunity at the intersection of three technology trends: wide-spread adoption of internet standards, cheaper internal computer components (circuits, CPUs, etc.) and faster wireless data transfer.

The group combined these technological trends with another trend at the time, the digitization of music, and came up with a simple idea: help music lovers play any song anywhere in their homes.

At the time, the only way to listen to music in your house was to wire together a stereo, amplifier and speakers. Then, if you wanted to listen to music you acquired digitally, you had to burn a CD and manually insert it into the stereo. Not the best situation.

Not to mention that the system was only useful for one room at a time — building a speaker system over multiple rooms required some serious DIY. And even if you spent energy building it, the music wasn’t easily coordinated between rooms.

The entire system was designed for a previous paradigm.

Sonos saw this and spent their first two years developing the product. They wanted to make the highest-quality audio product available, even if it meant taking longer or making their own parts. Everything was custom-built: the hardware, the operating system, the software. (Not unlike Apple.)

It wasn’t an easy engineering problem, but with several PhDs on staff and a belief in the product, Sonos became the point of integration in the new home audio value chain.

Problems with Sonos' Early Positioning

After they got the company rolling, the first major strategy decision Sonos made was deciding which speakers to add to their lineup, and at what price point.

Their first products were released in 2005: a wireless speaker, the ZP100, for $499 and a controller, the CR100, for $399.

This wasn't prohibitively expensive for their target market of wealthy homeowners, but there was a problem. Most people who downloaded MP3s online weren’t people who had high purchasing power or had a house to put multiple speakers in. They were college kids or young adults living in apartments.

Back then, you had to download MP3s from iTunes or an illegal peer-to-peer file-sharing website then load them onto a CD or iPod. The people who were willing and able to do this weren’t the same people with large, multi-room homes that Sonos speakers were designed for.

So while Sonos created a new technology that people wanted, their early products were a few years ahead of widespread adoption of digital music.

Over time, thanks to products like iTunes, Pandora, and Spotify, more and more people became comfortable with digital music. They also launched products like the Playbar to address the home theater market. This expanded the market for Sonos, and they continued to grow.

Sonos’ product positioning was focused on delivering the highest quality audio. But was this the right strategy? Would they have grown faster if they reduced prices and sacrificed audio fidelity, perhaps appealing to younger customers?

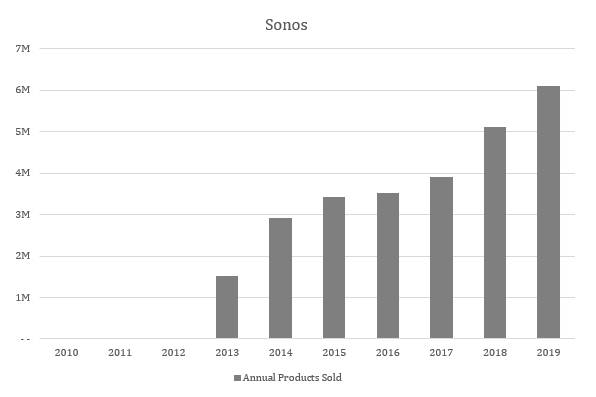

It wasn't until 2013 — eight years after the launch of their initial $499 product — that Sonos experimented with a more affordable option. They launched the Play:1, a speaker that retailed at $199. It ended up being quite popular and was a big contributor to their jump from 1.5 million products sold in 2013 to 3.4 million products sold in 2015.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!