Founders have long aspired to create products so innovative that they spawn entirely new business categories. While there’s allure to such dreams, it can be more strategic to build a company by disrupting existing categories. That’s the argument from James Evans, founder of Command AI (which was recently acquired), who outlines his framework in a four-step playbook in this essay. It’s the first for Every’s new Thesis column, which will bring thought-provoking big ideas every Monday to start off each week. Evans’s advice might feel counterintuitive to traditional markers of success in tech, but he’s found that such thinking can save founders years of hardship and deliver results sooner. It’s scary, but sometimes it’s better to lean into competition.—Kate Lee

As a founder, one of the strongest 180-degree turns I’ve made is my belief that, with rare exceptions, trying to create an entire business category from scratch is a much more arduous, wasteful, and potentially disastrous path than trying to disrupt an existing one from the start.

Category-creating businesses like Nvidia, which pioneered graphics processors, can become massive, world-changing operations—Nvidia’s GPUs are powering the AI revolution. But the odds of starting your business with paradigm-shifting aspirations and succeeding are lower than most founders realize.

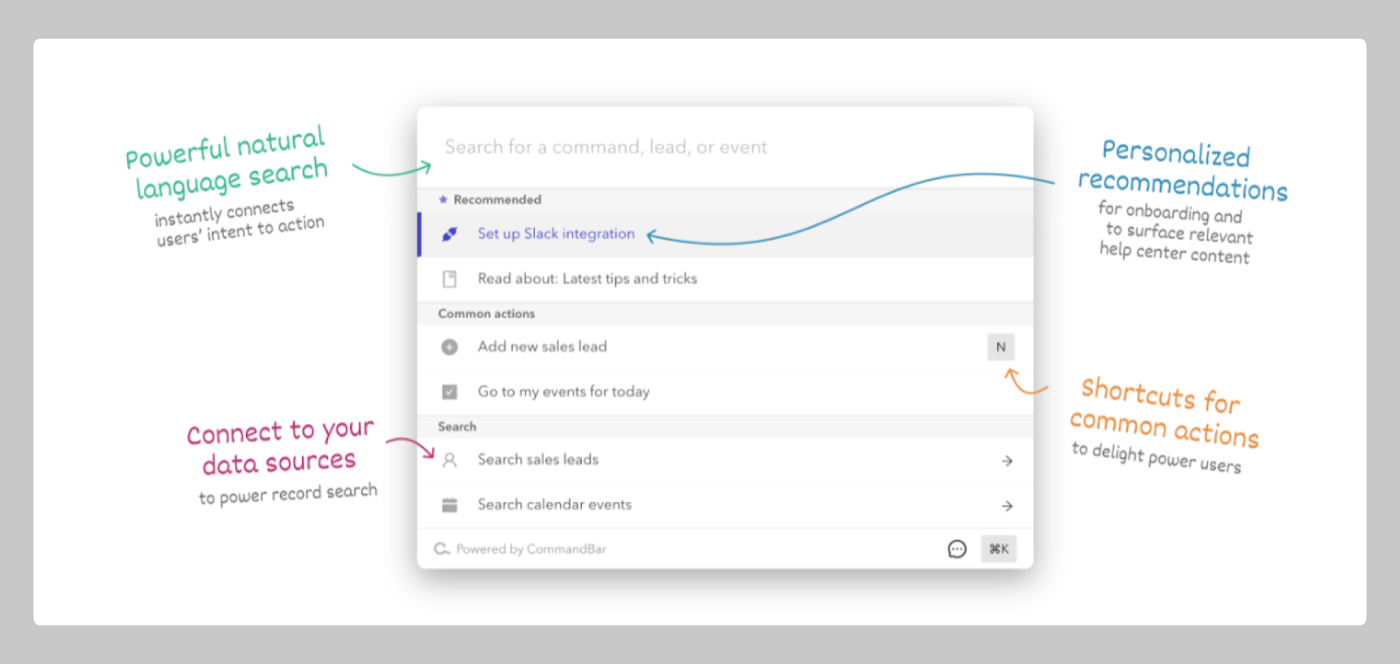

It’s a lesson I had to learn myself. Four years ago, my company, now called Command AI, started as a product called CommandBar that plugged into other software and let users summon a magical search bar with cmd + k or ctrl + k. (Command AI was acquired by the data analytics company Amplitude earlier this month.)

Users could then search the software using natural language. We felt that most software products were—and still are—too hard to use: There’s too much clicking around, too many unfamiliar terms, too many interactions with frustrating chatbots. We thought that CommandBar solved that problem.

We imagined a future where this search function would become a new universal building block for interfaces. In our Y Combinator application, we described the product as “the natural language interface for any software product.” We were creating our own category (the best name we could come up with was “product search”).

Source: All images courtesy of the author.Then we got stuck in the trickiest place for a startup. We found moderate momentum (great customer wins, good revenue growth, strong Series A funding) followed by the realization that it wasn’t scalable (no coherence among customers and unpredictable sales cycles).

The company’s growth only took off when we stopped trying to create a brand-new category and started competing within one—well, two, actually. Instead of focusing on a single way to help users, we now offer a menu of ways to influence users—a “user assistance platform”—that competes in two categories: chatbots and “digital adoption” software (aka pop-ups-as-a-service, or software that allows you to put pop-ups on your website). Our revenue growth rate has doubled, and growth feels much more effortless. We’ve been able to take our original vision—make software easy to use—and connect it to people who care. By labeling ourselves as competitors in those categories, we’re bat-signaling to the very people who feel the pain we strive to solve. We are winning by being less different.

It doesn’t sound as exciting as a futuristic vision of powering the next interface revolution, but it’s a way better business. We show up in market maps (those diagrams describing “10 vendors doing X” that venture capitalists post on LinkedIn), buyers find us more easily, and our demos take five minutes—not twenty-five.

I’m passionate about encouraging other software founders to take the category disruption—rather than creation—path because I think most founders don’t understand they can start that way. The conventional wisdom goes:

- Great businesses are built on great ideas.

- An idea has to be sufficiently novel to be great.

- I can’t succeed by building a startup that looks too similar to other companies.

Debunking this myth has never been more important, because the emergence of generative AI as a foundation technology offers up a more straightforward playbook for category disruption than ever existed before. Here’s how we did it.

Battling incumbents is tough but worthwhile

There are two ways to build a startup:

Become a paid subscriber to Every to unlock this piece and learn about:

- Finding categories with dissatisfied customers

- How AI enables faster competitive products

- Why smart positioning trumps total novelty

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.png)

.png)