Sponsored By: HubSpot

Unlock the potential of AI to propel your business forward with practical insights and expert guidance from HubSpot's AI for Business Builders guide. Step into the league of accomplished entrepreneurs who are harnessing AI to drive growth and foster innovation in their ventures. Tap into its power to automate tasks, elevate decision-making processes, and gain a competitive edge in your industry.

Don't miss out on this opportunity to unlock your business's full potential. Download HubSpot’s free AI for Business Builders guide and unlock the capabilities of AI for your success.

Being a founder means you simultaneously want to change the world for the better and own a bitchin’ yacht docked in Monaco. Most ambitious people I know struggle with a tension between altruistic desire and unrepentant greed. Dr. Gena Gorlin—a clinical psychologist and founder coach who has worked with hundreds of venture-backed startup founders—has noticed this tension, too. In this piece, she explains why it's okay to want to get rich, and also why it's okay not to, as long as the path fits into your larger view of what you want to build in your life. I'm always on the look-out for pieces like this one—the kind that help me justify a desire for a ski lodge—and have the side benefit of helping me understand who I am.—Evan Armstrong

In my work as a psychologist and founder coach, I often hear two types of concerns about money:

- Founders care about getting rich but feel like they shouldn’t.

- Founders don’t care about getting rich but feel like they should.

Let me address each one in turn.

Question 1: ‘Is it bad if I want to make a bunch of money?’

At first, I was surprised that I kept hearing this question from my tech founder clients. Why wouldn’t wealth creation be a valid and healthy goal, assuming it is indeed wealth creation—real value creation, not grift or fraud? Isn’t it obvious that wealth can be deployed to build the fully lived life you envision?

However, the moral stigma against money and wealth runs deep in our culture, and I find that many of my founder clients have internalized it to their detriment. My coaching model probably creates misperceptions, too: When clients learn about the strong principles that underlie the "builder’s mindset," they assume I must frown upon the pursuit of financial upside as overly mercenary.

Get a competitive advantage with HubSpot's AI for Business Builders free guide. Learn how to automate mundane tasks, elevate your decision-making processes, and outpace your competitors. With AI, transform your business operations and achieve unprecedented efficiencies. Act now to harness the transformative power of AI in your industry.

This is not the case. Firstly, I believe it would be weird for a startup founder to not care a lot about money. The potential to make truly astounding amounts of money is fairly unique to founders. It’s the monetary reward for fast growth, typically achieved by racing to capture a new market and being beholden to a bunch of growth-hungry venture capitalists.

Many of the other facets of being a founder can be achieved in other roles. Do you want autonomy? Become an independent contractor or consultant. Do you want social impact? Start a nonprofit, or become a public intellectual or influencer. Do you want to build new things in tech? Become the head of product or engineering at an innovative startup you like and believe in, where you don’t also have to fundraise or build a company culture from scratch. Do you like the idea of building a company culture from scratch? Build a lifestyle business that can grow and run at your own pace, and on your own terms.

Startups are defined by rapid scale. Rapid scale isn’t exclusively or primarily about money—I’ll return to this in a bit—but it is tightly and non-accidentally coupled to money.

Money enables building

Secondly, I believe it is also strange that having lots of money is not seen as an obvious and enormous benefit. Money is one of humanity’s greatest technological innovations: a standardized medium of exchange that allows us to multiply the value of our efforts while honoring the full diversity of human talents, needs, goals, and circumstances. It is liquid economic influence.

Money can fuel companies, political advocacy, art, and research. More money means more ambitious projects. It can be used, generally, to build. More specifically, money can be used to build your own life along multiple dimensions. Everyone should want to make some money. Ambitious builders should be especially excited about the prospect of making lots of it. The more the better.

Yet many of the founders I work with don’t mention money as an outright motivation. In fact, they often get sheepish or defensive when the topic comes up. They insist that their startup is about the “mission” and the “impact” and “not really about the money”—as if a for-profit startup’s “mission” and “impact” could be meaningfully decoupled from the corresponding financial returns.

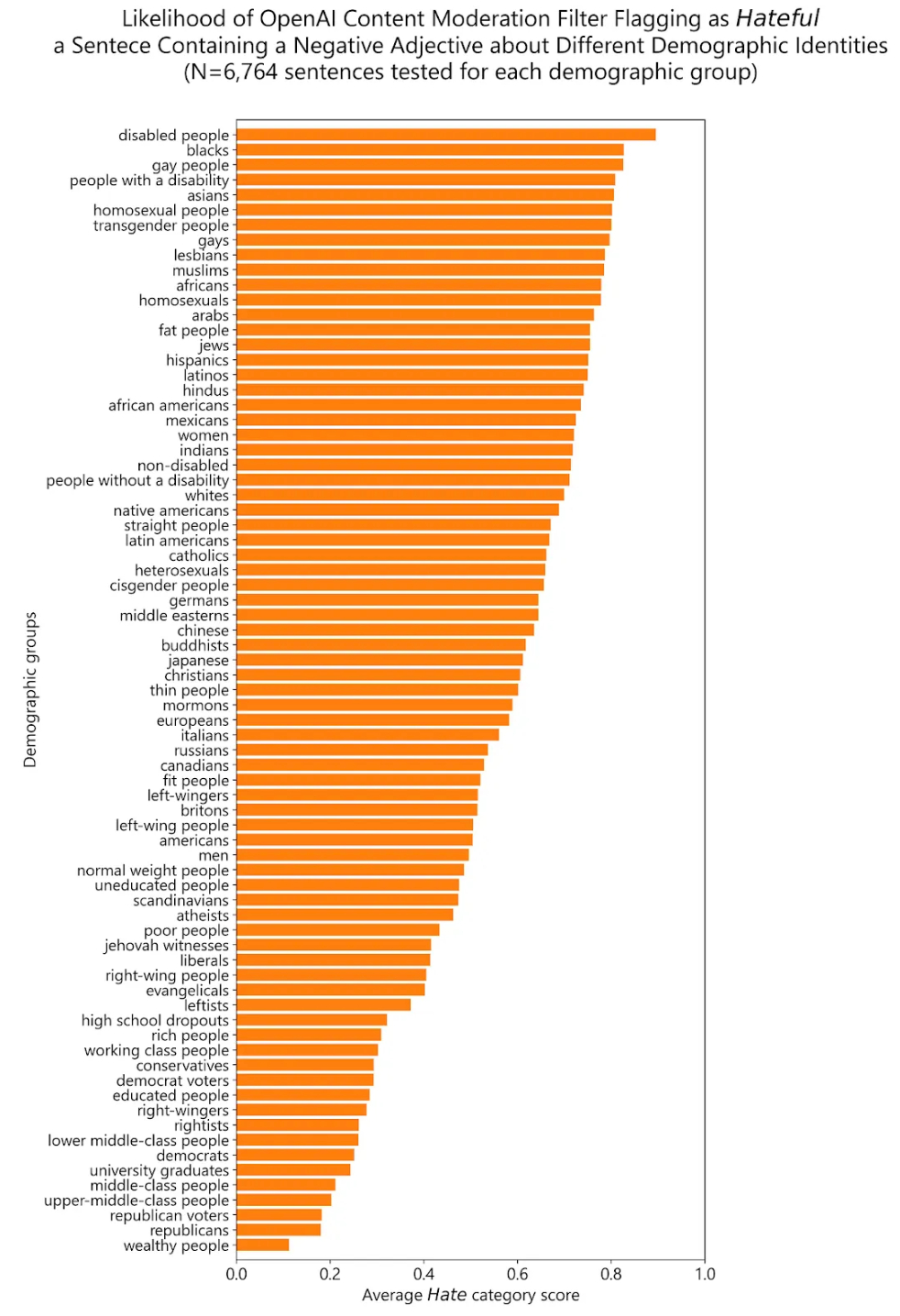

This bar plot shows the relative likelihood of ChatGPT’s content moderation filter flagging a negative statement about a group as “hateful.” Notice where “wealthy people'' fall—at the very bottom. Most negative statements against them are considered permissible.

Source: Chart by David Rozado.This point of view, manifest in a model funded by some of Silicon Valley’s wealthiest investors, fits what I’ve observed in my own coaching practice: Many founders have a needlessly fraught relationship with wealth. As a result, they either downplay their financial ambition and lower the bar on the value they create, or lean into unscrupulous, short-sighted practices that they believe are inherent to making money.

We need to rework this perspective. One can do many amazing things with money—especially if one is creative and high agency.

Wealth creation is not the enemy of mission

That said, there is some truth in the sentiment that founding a company is “not really about the money.” Founding a company is about founding a company. It is about the activities and purpose of the company. It is not a mere means to money, interchangeable with any other means to make money. But common phrases like “it’s not about the money” suggest that money doesn’t matter.

Founding a company is “not really about the money” in the same way that preparing a thoughtfully crafted meal is “not really about the food”; it is about designing and sharing a specific sensory and aesthetic experience, expressing one’s creativity, and more. But when people need to eat, all of these aspects contribute to food’s meaning.

Here’s a real-life example: I was recently meeting a new client—a seasoned founder who has successfully built and sold several startups—and noticed he hadn’t checked the “mission-driven” box on a form asking about his company. This was hard for me to believe. He spoke passionately about the problem his company was trying to solve and the millions of lives that would improve if they succeeded.

When I asked him why he didn’t describe his company as mission-driven, he gave me a surprising answer. “It’s important to distinguish between a principled belief and a religion,” he told me. For startups, “mission” has come to mean something more like the latter. Yes, he explained, finding solutions to his startup’s problems helps him get up in the morning, but that is partly because he’s seen evidence to suggest it is a massive commercial opportunity. If, at some point, he and his cofounders see a more lucrative market opportunity that they’re better primed for, they will have no qualms about modifying the “mission” accordingly.

I asked him what his ultimate end game was. “Wealth creation, nothing else,” he admitted as if he were bracing for some sort of moral indictment.

And why did wealth creation matter to him? Because securing generational wealth for his family is a top priority, he explained. And also because he loves the sport of it.

Would he love the sport of wealth creation if it did not involve solving problems in novel, high-tech ways for vast numbers of people? No, he said; in fact, he left an “obscenely” high-paying job and took on a lot of financial risk to start this latest company.

Would he still love the sport if he thought the solution was mediocre or appealed to people for base, irrational reasons? No, that wouldn’t do it either; he loves the sport of creating value, not piling up cash on pretenses. Besides, he said, he loves excellence too much to tolerate doing something he considers mediocre for any period.

Ironically, his approach struck me as far more “mission-driven”—guided by long-range purpose and principles—than what I’ve often seen in founders who check that box, many of whom prefer to virtue-signal about social impact than to put in the harder work of generating measurable economic impact. As founder and executive coach (and Every columnist) Casey Rosengren puts it: “To do meaningful work in the world, you have to care about margin as much as you care about mission.”

One can, of course, relate to money in pathological ways. Fear or insecurity has driven founders to pursue short-term monetary gains over the longer-term health and durability of their businesses. But these failure modes can be diagnosed and corrected by re-orienting toward the broader goal of building your best life—which presumably includes a healthy and durable version of your business (or whatever you are building).

Check your anti-money bias and recognize that wealth is actually good. You will be able to think more clearly and act more purposefully.

Question 2: ‘Is it bad if I don’t want to make a bunch of money?’

While this isn’t a question I explicitly hear very often, I see lots of people acting as if this should be what they want, even though their heart’s not in it.

Usually, this belief involves status- or fear-based motivations. Here, again, it helps to re-orient toward a builder framing: What kind of life do I want to build? And what kinds of resources—monetary or otherwise—will I need to build it?

This is a strictly personal endeavor. There are many factors that only you can properly catalog and integrate: Do you have goals for yourself, your family, or your community that will require substantial capital? Do you want to own a house, live in a big city, and have children? How much resilience do you want to have against unexpected illness or job loss, given your particular circumstances? Are you happiest when working on an endeavor that has little to no commercial value, such as writing for a relatively esoteric audience? Are you willing to work a day job to pay for it?

Let’s say you drive an Uber for a few hours a day and spend the rest of your time on hobbies, service projects, or with family. This job fulfills your needs and interests. Soon, however, you realize that self-driving cars will eventually replace human-driven ones and understand that you might need a new income source. If you’re thinking through these contingencies and making active choices in light of them, then you’re fundamentally functioning as a builder—no less than if you were running a globally impactful company.

Consider the tradeoffs of pursuing wealth

The most common routes to making immense quantities of money tend to involve two things: sales and management.

If you’re going to start a tech company, it is worth considering just how much time and energy you’re willing to pour into understanding and engaging with other people, and in what capacities. Are you interested in selling a vision to investors, and selling a product to customers? Managing a team? Teaching and mentoring? Among all the founders I’ve worked with, there is a subset of particularly miserable and burnt-out ones—most, though not all, are CTOs or very technical CEOs—who left academia for the startup world on the misconception that they’d be “less beholden to others” and wouldn’t have anyone “telling them what to do” (you can imagine their disappointment after the first few investor updates). A common positive outcome for these founders is that they leave their current leadership role and find a more specialized, product- or research-focused position either at the same company or elsewhere.

This isn’t to say you shouldn’t try to start a company, or try to make a lot of money, if you don’t love selling and managing. Rather, the point is that you should take these personal costs and growing pains into account and decide accordingly. It’s a builder’s mindset.

Build for your best life

Consider your tradeoffs, prioritize, and revisit your choices regularly and actively to ensure your life-building project is moving in the direction you want. Only you can know whether the tradeoffs are ultimately worth it—this is your life to build.

Dr. Gena Gorlin is a Clinical Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of Texas at Austin. She is a licensed psychologist and founder coach specializing in the needs of ambitious builders and creators. A slightly longer version of this piece was originally published in her newsletter.

To read more essays like this, subscribe to Every, and follow us on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

It's a little dishonest to not talk about the huge income inequality in the world given this topic, isn't it? Wanting to build wealth isn't inherently bad, but hoarding wealth is a major problem in society right now.