Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

Kyla Scanlon is good at the internet. She is the rare economics commentator who has become popular not for having sensationalist takes, but for producing smart and accessible explainers that people under the age of 60 like. The 27-year-old Kentucky native, who coined the term “vibecession” in June 2022, has amassed 172,000 followers on X. She just published her first book, In This Economy?: How Money and Markets Really Work.

Scanlon isn’t just a popular economics commentator—she’s a helpful stand-in for anyone trying to understand how Gen Z views economic theory in the context of today’s markets. In case you have forgotten, things have been, like, kinda weird over the last decade. But this is economics revisited for a generation that was in elementary school during the 2008 financial crisis, and for whom the pandemic economy, and the resultant inflation, has commanded much of their adult experience. The America portrayed in most economics textbooks, one where if you work hard, you can afford a house and make a comfortable living, is largely gone. Instead, it is a stranger, more complicated place.

In This Economy is an attempt to help the layperson understand the underlying forces driving all this weirdness. It’s the kind of book you may give to a high schooler asking questions about the economy for the first time—not quite a textbook, not quite a theory proposal. Scanlon starts with the most fundamental concepts, such as how money works and supply and demand. From there she springboards into newsy items and theories as diverse as Marxism, how “Taylor Swift tickets show the influence of corporations and how sometimes price fluctuations are not just about supply and demand,” why the gold standard is no longer a good idea, and the collapse of the crypto exchange FTX.

Where Scanlon is most inventive is in her serious study of “vibes,” which she defines as “our collective feelings about the economy.” The idea that emotions play a role in the economy isn’t new. My more economics-oriented readers could consider vibes as a term loosely adjacent to consumer sentiment or Keynes’s notion of the animal spirit.

Her concept has more depth than those theories. I would characterize economic vibes as collective feelings in the digital age. Almost all previous versions of economic theory around consumer sentiment have been formed in a pre-internet world. Until now, no one had updated those frameworks for the age of algorithms. When I emailed Scanlon about how she would compare her theory to Keynes's, she told me, “Keynes is around fundamentally psychological forces that drive economic decisions, whereas vibecession is a disconnect between data and sentiment.” Now that services like Instagram and TikTok—whose primary value proposition is entertaining emotional manipulation—provide such an abundance of data, vibes feel (ha!) like a bigger idea to me.

The book is particularly fascinating because Scanlon herself is subject to the vibes. I disagree with some of her assumptions, but their very difference from mine was why I read the book. My guess is that informed readers who do a close read will similarly find spots that will raise eyebrows. Scanlon portrays big ideas as facts, when sometimes they are feelings. For example, she writes this throwaway line at the conclusion of a chapter on the labor market:

“The labor market is going to be shaken up by various events over the coming years. For example, Artificial intelligence (AI) is speeding towards us; at an unimaginable pace. That’s terrifying, and we don’t know the full extent of the repercussions yet. It’s part of the reason things feel so weird right now. We never really know what the future is going to look like, but man, it sure does feel uncertain.” [Emphasis added]

This is a big idea! Many people believe that AI is a large labor market disruption, and some of them are hyper-online. However, if that’s what you think, it’s probably worth diving deeper instead of pulling the pin on an emotional grenade at the end of chapter. If you are skimming the book, you probably wouldn’t notice these small moments, but they occur frequently enough on close examination that they detract from Scanlon’s stated goal to produce an accessible and accurate explainer.

Vibes acted as an editorial filter, and I was curious to see what concepts made it through. Summarizing the entire field of economics and markets in one 259-page book is essentially impossible. What she chose to include—and how she chose to characterize it—is an argument in and of itself that vibes are a concept that should be taken seriously.

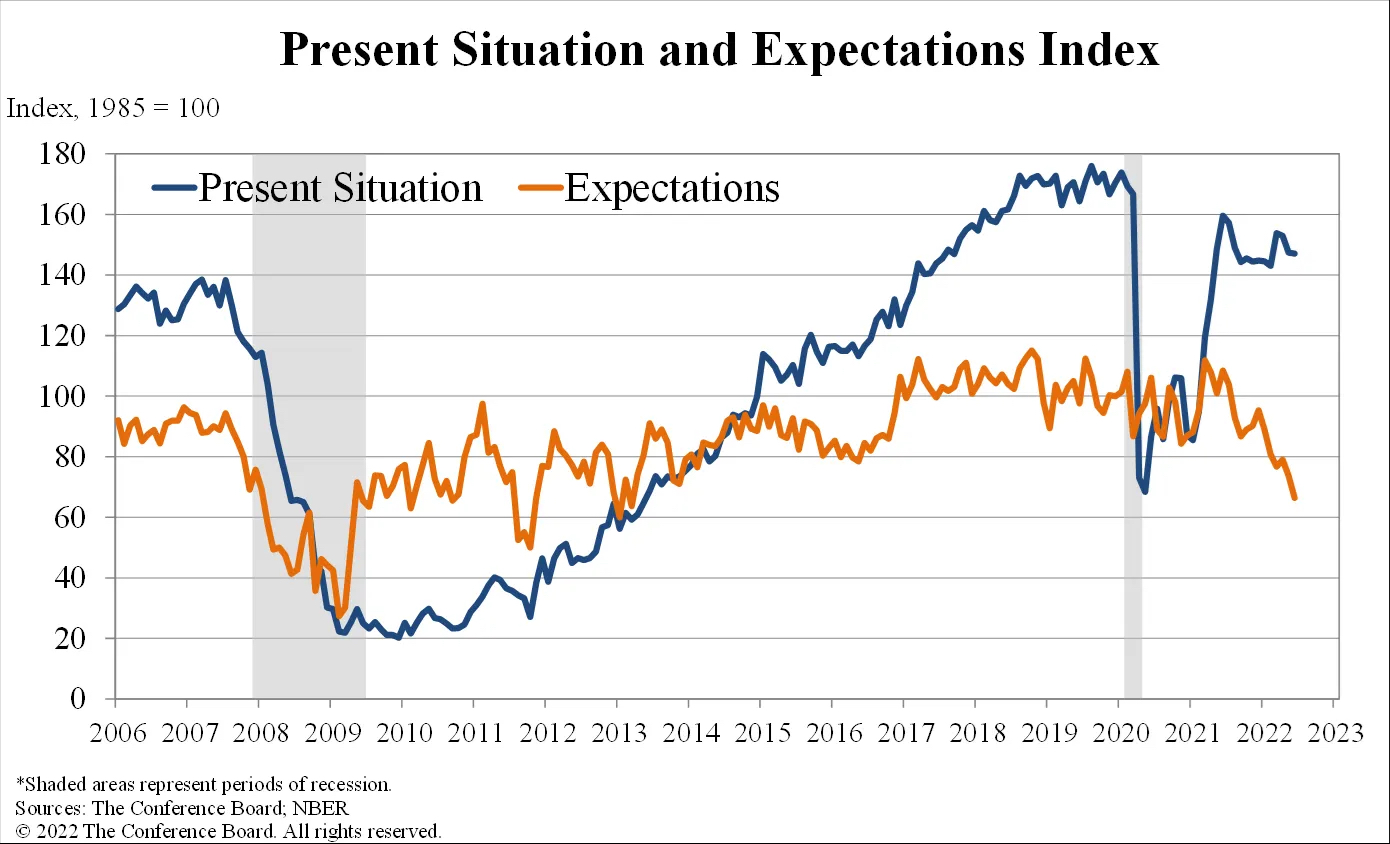

The most concrete example comes from her original Substack post in which she coined the term vibecession. In her piece, she argued that the split between how consumers felt about their current situation (quite good) and how they thought the future would go (quite bad) could end up being a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Source: The Conference Board.Thankfully, in America, at least, they were wrong. The bad vibes didn’t get us, and the economy bounced back. However, if enough people had believed that narrative and reduced their spending habits, they could’ve made a recession happen. Scanlon’s argument is that the economy is downstream of emotions. Which, when said out loud, feels obvious, but it hasn’t been taken seriously. Most study of emotion in the field has been confined to behavioral economics: Economists study individual patterns of irrational behavior, such as the sunk cost fallacy or anchoring bias. But few people have studied the impact of emotions on the population.

Vibes are a field of study that deserves more attention and funding. In the most fun version, Scanlon would be gifted a $50 million pot of money for her to let loose on the trading markets. If vibes are as predictive as I think they could be, she could make all sorts of fun trades. The trading strategy would be something like:

- Create a vibe measurement system to classify and measure consumer sentiment.

- From these metrics, create a "vibe index" using social media sentiment analysis and LLMs to forecast consumer behavior.

- Profit.

It’s not uncommon for hedge funds to scrape Reddit forums for stock picks so they can front-run meme stocks like GameStop and AMC (I know of a few). But Scanlon’s idea is more interesting than that. If we can learn to understand and forecast emotion, we should be able to do the napkin math about the spending and saving habits of the American populace.

Unfortunately, for her stated purpose to have written an economics explainer, the book isn’t as competitive with more accurate and thorough works. Most books that attempt a similar breadth end up two- to three-times the length of Scanlon’s. She is trying to address a very real need—there is an incredible amount of misunderstanding on how the economy works today. However, her writing is so vibe-influenced, and her explainers so opinionated (while being presented as purely factual), that I would struggle to recommend the book on that basis. This is particularly true is her treatment of economic theories.

Scanlon is immensely talented and onto something important. I wish she had devoted multiple chapters exclusively to vibes. Her editor should have given her the confidence to go for it and write the definitive book on the vibes-based economy. Don’t bother with the explainers or Taylor Swift, just go straight into why emotions deserve to be a field of economic study. Ninety-nine percent of economists will go through their entire careers without coining a term or building the fandom that Scanlon has—she should’ve doubled down and proved her point with mathematical rigor. I’m sure this won’t be her last book, and I’m anxious to read her next. In the meantime, if you want to understand how your customers or younger co-workers view the markets, In This Economy? is a good-enough proxy.

Evan Armstrong is the lead writer for Every, where he writes the Napkin Math column. You can follow him on X at @itsurboyevan and on LinkedIn, and Every on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!