Sponsored By: Alts

This essay is brought to you by Alts, the best place for uncovering new and interesting alternative assets to invest in.

Figma was one of the largest software acquisitions of all time at $20B—a staggering, Scrooge-McDuck-swimming-in-a-pool-of-gold sum of money. More remarkable than the money is the possibility that this deal is a failure for many of the VCs who backed Figma. All it would take is for the investors to have used capital out of their current funds.

At the time of exit, Index Ventures owned ~13% of Figma, for a stake worth about $2.6B. The firm led the seed round of the company in 2013 and almost certainly defended its ownership over the intervening years by injecting additional capital. Depending on timing and volume of deployment, they likely got 30-90x their capital. That’s great—but it isn’t enough.

Index’s most recent fund was raised in 2021 with $3.1B in total assets under management (AUM). Even though Figma was a $20B outcome, even though Index owned more stock than the founder of the company, this company wouldn’t even be enough to return the fund. A good fund will return at least 3x the investor’s capital. To clear that bar, Index will need multiple Figma-sized outcomes. The typical venture fund will have 1-2x breakout winners, a few more that might double their investment, and the rest will go to zero. This is a grand slam industry—VCs aren’t in the business of base hits. To be fair to Index, the $3.1B they’ve raised is spread between different types of investment vehicles from seed to growth, but the point is still valid. The larger the fund size, the more outsized the outcomes need to be.

We have now reached a point in the startup ecosystem where for large VC funds, a startup achieving a billion-dollar outcome is meaningless. To hit a 3-5x return for a fund, a venture partnership is looking to partner with startups that can go public at north of $50B dollars. In the entire universe of public technology companies, there are only 48 public tech companies that are valued at over $50B. Simultaneously there are close to 1,000 venture funds all trying to find these select few. This is a huge problem. It is likely that many of the funds deployed over recent years will be some of the worst-performing of all time.

It isn’t just limited partners who are being ill-served by the venture capital product—entrepreneurs are getting hosed too. Since VCs typically only have 20-30 companies per fund, they end up doing a large degree of “pattern recognition” for their portfolio companies, resulting in a small subset of ideas being funded. The people behind these ideas almost always end up looking the same: white, Ivy League, and elite. Just 0.12% of the venture dollars deployed in Q3 this year went to Black entrepreneurs.

To hit this $50B hurdle, entrepreneurs take on more and more risk to try and achieve larger and larger outcomes. There is an entire generation of entrepreneurs who are ambitious and highly qualified who can’t receive venture dollars because they look or act a little differently. Even for those founders who are building a “world-changing” company, this push to enormous outcomes forces them to embrace an insane amount of risk. Any experienced builder will tell you that at certain growth milestones, the end state of the business becomes obvious. For those who take VC dollars, there is no off-ramp to becoming a giant company.

This is a market ripe for disruption. As venture funds continue to target larger and larger outcomes, there is a ton of opportunity left on the table that no one is seizing. You could invest in businesses that have an 80% chance of being worth $300M, rather than a 1% chance of being worth $80B. This strategy is an obvious opportunity to make a ton of money. Start by serving the underfunded, slowly move upmarket, and then, suddenly, you’ve disrupted the entire industry.

(Reader, I beg you, please use this strategy and become rich. And not only will you become rich, but you’ll also enable a wholly new class of entrepreneurs and small businesses in America. Get rich, do social good, and validate this article? Why wouldn’t you pursue this??)

To understand how this is possible, we first need to understand how it occurred. If you want to win at something as complex as startups, you have to understand the game behind the game—in this case, the funding dynamics.

Power screwed

Everyone working in venture capital is smart. You don’t get to play the game of high finance without having some amount of capability. The VC product becoming subpar isn’t the result of stupid decisions or people ignoring obvious data. It’s the result of multiple parties making individually rational choices that have resulted in systemic levels of risk.

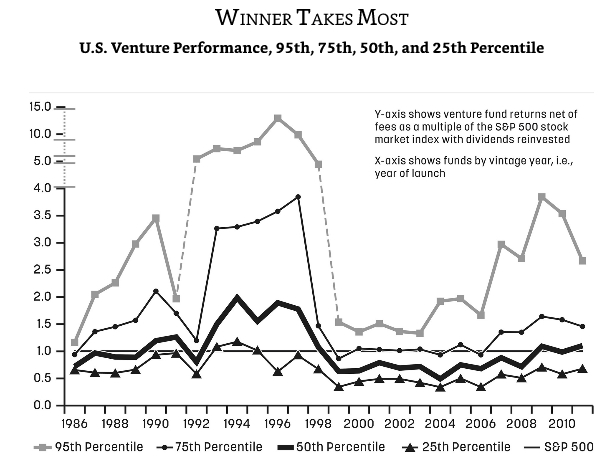

The data point that the industry has over-indexed on is the power law, in which a large majority of returns will be generated by a tiny subset of players. It applies to venture funds (where the top 5% of funds significantly outpace the median).

It also applies to startups, where one in 20 in a venture capital fund’s portfolio will return the entire fund. When it works, it works fabulously well. Great VC funds can get their investors 5-10x their money back. Successful founders become billionaires.

This is not new information. We are now in a post-Power Law meta where this understanding has disseminated throughout the entire industry, so everyone starts making newly rational choices. The thinking flows something like this:

- Startups: “The best investors are only interested in the biggest opportunity so I have to swing for the fences.”

- VCs: “The only investments that matter are the top 1% so price doesn’t matter.”

- Limited partners: “The only funds that return are the top 5% so I want to give as much money as possible to blue chip firms.”

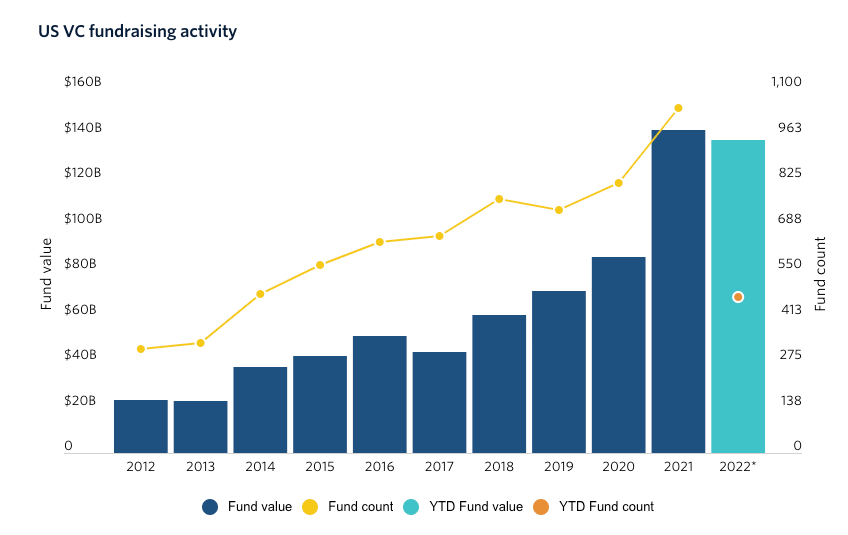

The money available to winners has enticed more and more asset managers into the space:

Data from Pitchbook.Simultaneously there has been an influx of capital from sovereign wealth funds, pension funds, and endowments pumping up the total volume of dollars into the sector. The most infamous example is Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, which put $45B into Softbank’s $100B Vision Fund—a decision made in a 45-minute meeting (wouldn’t we all like to work at a billion-dollars-a-minute rate?). But it isn’t just the Saudis—sophisticated fund managers at places like Stanford are operating under similar logic:

“Stanford has been no different. As of 2021, private equity, which includes VC funds, accounted for 33% of Stanford’s asset allocation, an increase from about 25% in 2015 when Wallace started at the endowment….Over the past decade, VC funds in Silicon Valley, China, and India have delivered $10.9 billion in returns to Stanford, according to its financial reports. That success has encouraged the endowment to expand in VC. It’s more likely to double down on existing winners…than add funds to the mix. [At] Stanford seven years ago, the school had 300 investment funds in its portfolio. By 2020, [they] had nearly halved that number to 175, The Financial Times previously reported.”

Sponsored By: Alts

This essay is brought to you by Alts, the best place for uncovering new and interesting alternative assets to invest in.

Figma was one of the largest software acquisitions of all time at $20B—a staggering, Scrooge-McDuck-swimming-in-a-pool-of-gold sum of money. More remarkable than the money is the possibility that this deal is a failure for many of the VCs who backed Figma. All it would take is for the investors to have used capital out of their current funds.

At the time of exit, Index Ventures owned ~13% of Figma, for a stake worth about $2.6B. The firm led the seed round of the company in 2013 and almost certainly defended its ownership over the intervening years by injecting additional capital. Depending on timing and volume of deployment, they likely got 30-90x their capital. That’s great—but it isn’t enough.

Index’s most recent fund was raised in 2021 with $3.1B in total assets under management (AUM). Even though Figma was a $20B outcome, even though Index owned more stock than the founder of the company, this company wouldn’t even be enough to return the fund. A good fund will return at least 3x the investor’s capital. To clear that bar, Index will need multiple Figma-sized outcomes. The typical venture fund will have 1-2x breakout winners, a few more that might double their investment, and the rest will go to zero. This is a grand slam industry—VCs aren’t in the business of base hits. To be fair to Index, the $3.1B they’ve raised is spread between different types of investment vehicles from seed to growth, but the point is still valid. The larger the fund size, the more outsized the outcomes need to be.

It has been a terrible time for technology investing.

The S&P is down. The NASDAQ is down. And crypto is very, very down.

But did you know that comic books are way up? Or that tickets are mooning? Or that farmland is completely unaffected?

That's why I’ve been reading Alts. These guys analyze the heck out of alternative investment markets, and you reap the rewards.

Stefan and Wyatt provide original research and insights to help you become a better investor. More than just do a daily summary email, these guys do research.

Join 50,000 other investors and find out what you've been missing.

We have now reached a point in the startup ecosystem where for large VC funds, a startup achieving a billion-dollar outcome is meaningless. To hit a 3-5x return for a fund, a venture partnership is looking to partner with startups that can go public at north of $50B dollars. In the entire universe of public technology companies, there are only 48 public tech companies that are valued at over $50B. Simultaneously there are close to 1,000 venture funds all trying to find these select few. This is a huge problem. It is likely that many of the funds deployed over recent years will be some of the worst-performing of all time.

It isn’t just limited partners who are being ill-served by the venture capital product—entrepreneurs are getting hosed too. Since VCs typically only have 20-30 companies per fund, they end up doing a large degree of “pattern recognition” for their portfolio companies, resulting in a small subset of ideas being funded. The people behind these ideas almost always end up looking the same: white, Ivy League, and elite. Just 0.12% of the venture dollars deployed in Q3 this year went to Black entrepreneurs.

To hit this $50B hurdle, entrepreneurs take on more and more risk to try and achieve larger and larger outcomes. There is an entire generation of entrepreneurs who are ambitious and highly qualified who can’t receive venture dollars because they look or act a little differently. Even for those founders who are building a “world-changing” company, this push to enormous outcomes forces them to embrace an insane amount of risk. Any experienced builder will tell you that at certain growth milestones, the end state of the business becomes obvious. For those who take VC dollars, there is no off-ramp to becoming a giant company.

This is a market ripe for disruption. As venture funds continue to target larger and larger outcomes, there is a ton of opportunity left on the table that no one is seizing. You could invest in businesses that have an 80% chance of being worth $300M, rather than a 1% chance of being worth $80B. This strategy is an obvious opportunity to make a ton of money. Start by serving the underfunded, slowly move upmarket, and then, suddenly, you’ve disrupted the entire industry.

(Reader, I beg you, please use this strategy and become rich. And not only will you become rich, but you’ll also enable a wholly new class of entrepreneurs and small businesses in America. Get rich, do social good, and validate this article? Why wouldn’t you pursue this??)

To understand how this is possible, we first need to understand how it occurred. If you want to win at something as complex as startups, you have to understand the game behind the game—in this case, the funding dynamics.

Power screwed

Everyone working in venture capital is smart. You don’t get to play the game of high finance without having some amount of capability. The VC product becoming subpar isn’t the result of stupid decisions or people ignoring obvious data. It’s the result of multiple parties making individually rational choices that have resulted in systemic levels of risk.

The data point that the industry has over-indexed on is the power law, in which a large majority of returns will be generated by a tiny subset of players. It applies to venture funds (where the top 5% of funds significantly outpace the median).

It also applies to startups, where one in 20 in a venture capital fund’s portfolio will return the entire fund. When it works, it works fabulously well. Great VC funds can get their investors 5-10x their money back. Successful founders become billionaires.

This is not new information. We are now in a post-Power Law meta where this understanding has disseminated throughout the entire industry, so everyone starts making newly rational choices. The thinking flows something like this:

- Startups: “The best investors are only interested in the biggest opportunity so I have to swing for the fences.”

- VCs: “The only investments that matter are the top 1% so price doesn’t matter.”

- Limited partners: “The only funds that return are the top 5% so I want to give as much money as possible to blue chip firms.”

The money available to winners has enticed more and more asset managers into the space:

Data from Pitchbook.Simultaneously there has been an influx of capital from sovereign wealth funds, pension funds, and endowments pumping up the total volume of dollars into the sector. The most infamous example is Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, which put $45B into Softbank’s $100B Vision Fund—a decision made in a 45-minute meeting (wouldn’t we all like to work at a billion-dollars-a-minute rate?). But it isn’t just the Saudis—sophisticated fund managers at places like Stanford are operating under similar logic:

“Stanford has been no different. As of 2021, private equity, which includes VC funds, accounted for 33% of Stanford’s asset allocation, an increase from about 25% in 2015 when Wallace started at the endowment….Over the past decade, VC funds in Silicon Valley, China, and India have delivered $10.9 billion in returns to Stanford, according to its financial reports. That success has encouraged the endowment to expand in VC. It’s more likely to double down on existing winners…than add funds to the mix. [At] Stanford seven years ago, the school had 300 investment funds in its portfolio. By 2020, [they] had nearly halved that number to 175, The Financial Times previously reported.”

All of these choices make sense on the micro level, but on the macro level, they’re breaking the system. This applies to VC funds too.

System players

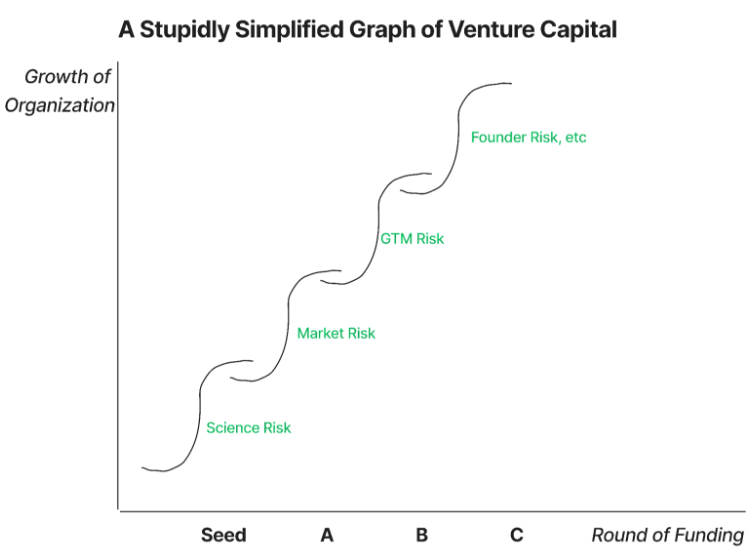

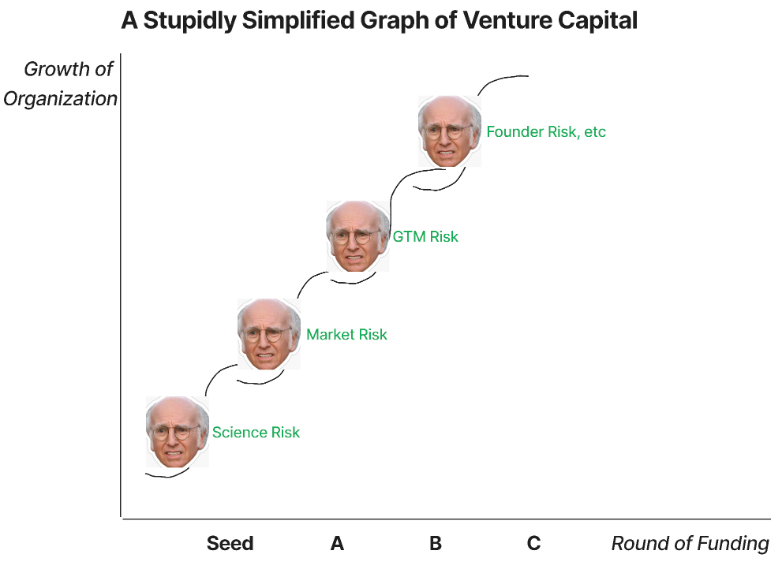

Here’s how venture should work: a round of funding is used for defined hypothesis testing. An entrepreneur will pitch that “I think X solution will solve Y problem and we need Z funding to see if that is true.” Each successive round of funding can then be used for additional experiments to derisk new parts of the business. At a point where the scariest risks are taken off the table, the company goes public. Everyone wins! It would look something like this beautiful graph that I made in two minutes (you can swap whatever risk you care about at any point in the journey):

This is never how it actually happens, but you get the idea. Startups should receive risk capital to literally derisk certain aspects of the business.

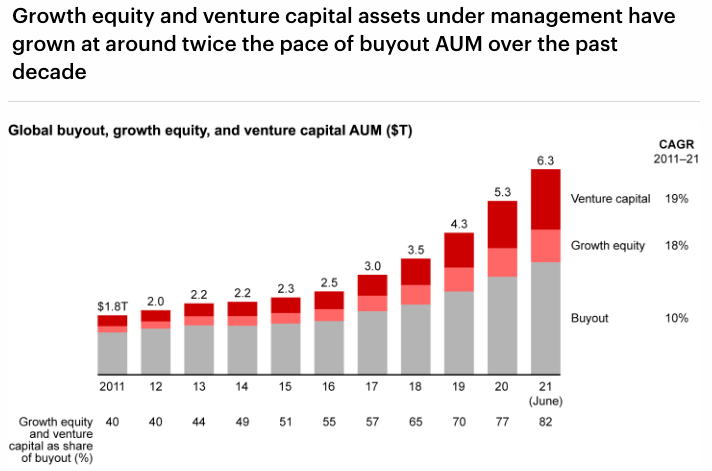

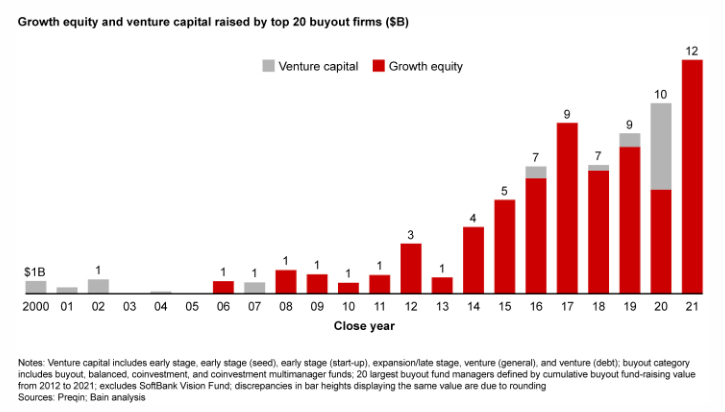

However, over the last decade or so, something shifted. Traditional venture funds that specialized in early-stage risk started to add buckets of “growth equity” that were supposed to be utilized for the derisked businesses looking to delay a public market debut.

Because VCs receive 2% of their assets under management every year as a fee, adding a growth fund became a great way to give yourself a fat raise.

To add to the mania, hedge funds and private equity funds pushed into startup investing to also do growth equity. Look at this data from Bain.

Keep in mind that all of these funds are still competing to find and fund the top 1% of companies. Put this all together, and enormous amounts of additional risk will be accepted at later stages and valuations will skyrocket.

It’s tempting to subscribe to the heroic stereotype of venture capital: the lone contrarian, bucking social convention, and investing in entrepreneurs when no one else believes in them is the mythos of the VC. Unfortunately, this tale wildly diverges from reality.

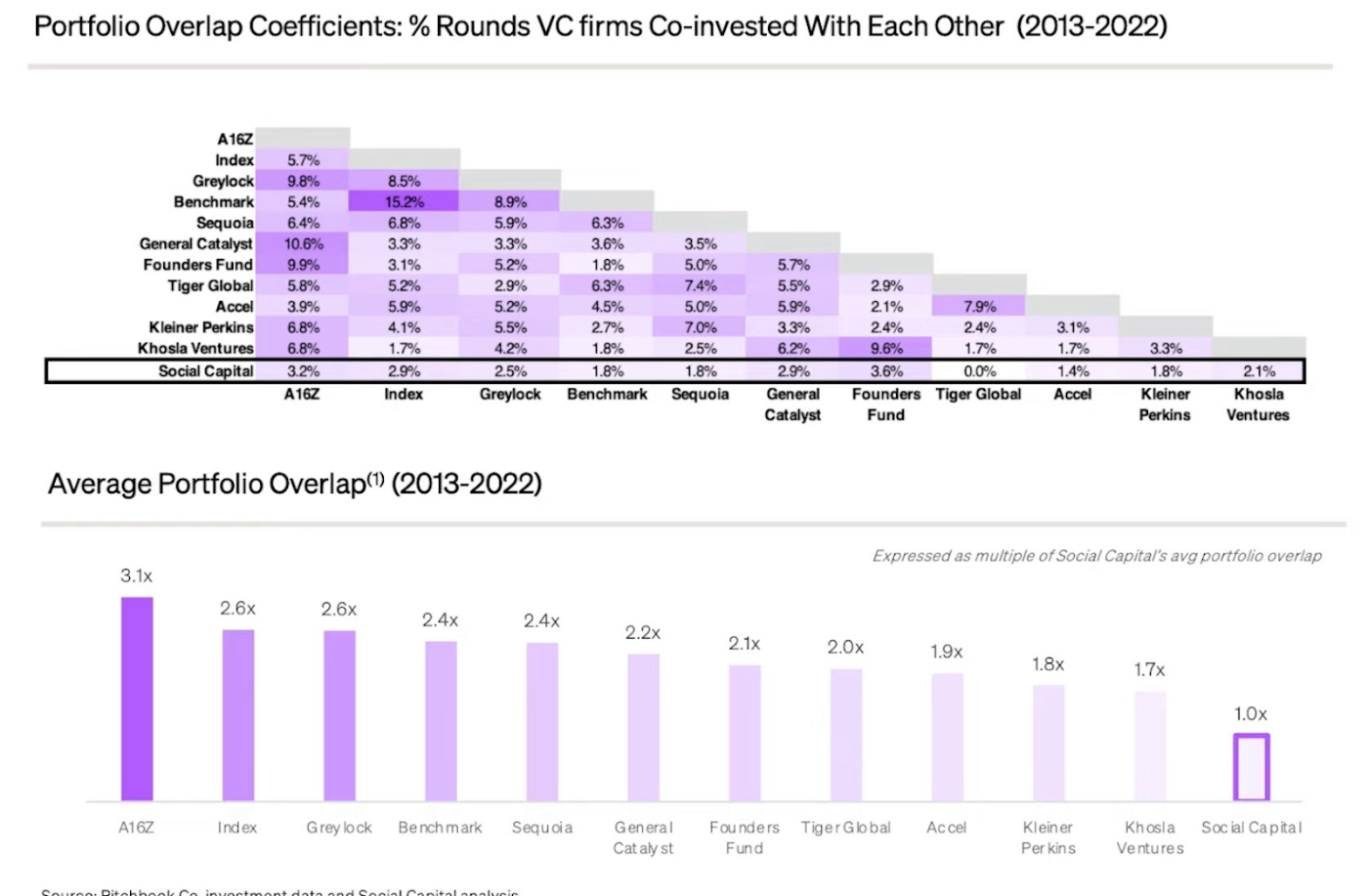

The typical funding round in a startup will consist of 3-5 major funds taking a bet, then with a variety of smaller checks, sometimes numbering 50-plus, putting capital in. The top funds have started to have large amounts of overlap in their investments, as shown by a recent analysis by venture fund Social Capital.

Power law logic, coupled with soaring AUM, welded with growth equity funds, has resulted in a venture strategy that will compress returns. Mega-funds ($500M+) accounted for 77% of capital raised by venture funds in the first half of 2022, with an average fund size of $317 million.

Not only are returns concentrated to those singular companies, but even those don’t always work out. Since LPs are fighting to put as much money as possible into these funds they get the double whammy of having multiple funds concentrated in the exact same failing companies. Uncorrelated used to be a word LPs loved, multiple distinct winners across multiple funds with little to no overlap. Those days are long gone and with it an invaluable principle of traditional portfolio construction.

If you want to build anything less than a $50B company, this product is not meant for you. To be fair, this venture product does work for some! It is still a good way to make money if you’re building or funding enormous companies. But the product continues to move upmarket and is abandoning significant fiscal opportunity. What is more important is that it doesn’t work for most companies.

What does a solution look like?

I want to return to my silly S-curve risk graph from above. What happens to the founder when they conduct this experiment and the result is meh?

Maybe the market is smaller than you thought, or you won’t be able to scale as quickly as predicted. If you have accepted venture capital you only have two options: shut down the business or pivot. This is the case even if you have a solid business that would comfortably be a $20 million-plus revenue enterprise. Again we are left looking for an alternative to traditional venture capital because these businesses deserve more options.A capital allocator would need to have two things happening simultaneously.

- Limited fund size: The fund would need to be $150M or less, or otherwise, you’ll be back to being wholly subject to the power law.

- Equity optionality: Investors in a startup utilizing this product need to be able to get returns even if the outcome is smaller. That would require an equity buyback or revenue share structure to ensure liquidity even if the business isn’t big enough to go public.

In an ideal world, most of the companies in this fund’s portfolio would at least return their investment with a few companies doing exceptionally well and performing like a traditional venture-backed startup. However, a mere $500M or billion-dollar outcome would be all that is necessary to make it work as compared to the $50B that is required of mega-funds.

The best example of this alternative product is Indie.VC, run by Bryce Roberts. Over the course of 6 years, Indie invested in 40 companies. It held the two key components of limited fund size and gave equity optionality through redemption clauses or equity buybacks. The results are encouraging, with a 51% IRR and 4.3x TVPI, while 87% of the companies generate returns with 54% doing over $1M in revenue, 30% doing over $5M, and 10% over $10M. It did all this while having a 50/50 split between male and female founders, with 20%+ being black founders.

So if, hypothetically, Indie solved this crisis, why isn’t this strategy common practice?

What are the blockers?

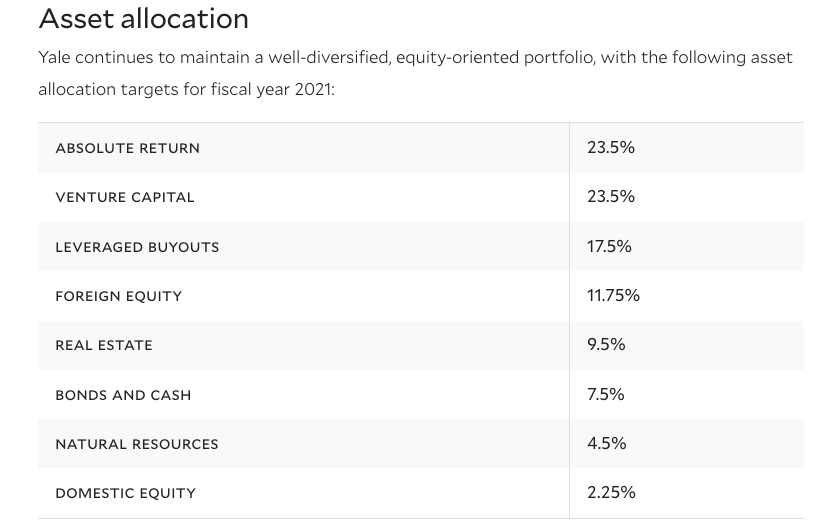

There is an old saying in enterprise software, “No one is fired for buying IBM”—people mitigate risk for their decisions by choosing the consensus option. This occurs even in the supposedly risky world of venture capital. Limited partners’ fund managers are generally compensated on a salary basis and are not incentivized to take risky bets. They look for consistent winners within their clearly defined buckets of allocation. The chart below is how Yale publicly defined their $41B endowment’s asset buckets in 2020.

Yale, looking to deploy $9.4B into venture capital, is only going to be putting their money into the Sequoias and Benchmarks of the world. If some plucky fund manager came along saying that they had a product that probably couldn’t scale past $150M and that also had an entirely different risk profile? Not even worth taking the meeting.Even if they take the meeting, you’ll still have a hard sell! The entire theological tradition of startups is based on the power law. Telling people that their fiscal religion has led them astray is rough, especially when said religion has given them extraordinary returns over the last ten years. This is exactly what happened to Indie and why it had to pause operations. Getting LPs to care and to commit just wasn’t working.

I’m also worried about the solo fund pursuing this strategy. Startups that do successfully climb the S-curves will require additional capital support, but a fund of this size will only be able to do that in limited quantities. One important advantage VC has is an enormous ecosystem of capital, service providers, and success stories. A fund pursuing this strategy would have to build all of that from scratch.

Where do we go from here?

The original name for venture capital was adventure capital. Technology’s life-giving veins used to be lined with copper and silicon. It was the spark of the soldering gun, the ring of the hammer that were the sensory signals of Silicon Valley. In dilapidated workshops and musty garages, tinkerers tried to make cool stuff and see where that took them.

An incredible adventure does not require summiting Everest. It can be as simple as ascending to the top of your local hill. If you happen to end up at the top of a mountain, great! But adventure only occurs when you don’t know the destination. VC is designed for breakthrough technologies, not for all successful technology businesses. When a sector goes out of favor or proven technologies become commonplace, VC funding dries up. Entrepreneurs deserve an asset class that supports them in whatever journey they end up taking.

Thanks to Bryce for being a sounding board for these ideas and for sharing some of Indie’s performance data. To discuss Bryce's future plans for indie, feel free to slide into his DMs or reach out to him directly at [email protected]

Ideas and Apps to

Thrive in the AI Age

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Ideas and Apps to

Thrive in the AI Age

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!