Due to continued strength of the Walmart.com brand, the company will discontinue Jet.com. The acquisition of Jet.com nearly four years ago was critical to accelerating our omni strategy.

What can we take away from this passing?

Jet’s Early Days

Say you want to compete with Amazon. How would you do it?

Marc Lore, who previously founded Quidsi (aka Diapers.com) and sold it for $535 million, had an idea. Amazon competed on price and convenience. What if a company competed only on price? With this in mind, he began working on the company that would become Jet.com.

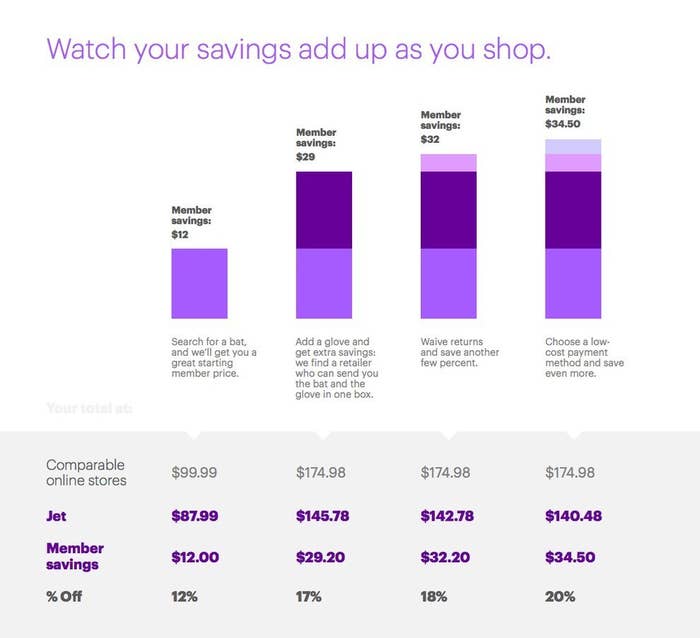

Jet’s innovation was their “Smart Cart”. It utilized a concept called price scheming. Price scheming dynamically updated the prices of goods as customers added them to their cart to give them lower prices.

See, shipping and fulfillment costs are lower when you ship from the same distribution center. So if you added something from a warehouse in Texas, other items in that warehouse would be cheaper on Jet.com because the distributor could package them together. Additionally, customers could get further savings on Jet.com by using a cheaper payment method (such as debit) or agreeing to not return an item.

(Source)

The first few months after launch, Jet actually exceeded sales expectations. However, revenue wasn’t the main issue for Jet.

Zero LTV?

The main issue with Jet was unit economics. Investors focus on LTV to CAC in the early days of a startup because if a company has a positive LTV to CAC ratio, it can acquire new customers even if it means burning cash. When that happens, it means the cash is coming in a future time period.

However, it seemed Jet wasn’t making very much gross profit at all. At their launch, Jet fulfilled its orders in three ways.

One-third of customer orders Jet fulfilled itself: it purchased goods from manufacturers at wholesale prices.

Another third was fulfilled by partner merchants. For these items, Jet bought from other merchants at retail prices.

The remaining third was purchased by Jet’s “concierge service”: Jet would list an item on it’s website that it didn’t own, then Jet employees would actually search other websites for that product and order on behalf of the customer. Jet would pay whatever price it took.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!