Sponsored By: Maven

This essay is brought to you by Maven.com, the home of career-building cohort-based courses that help ambitious professionals to level up, get promoted, and build new skills.

If only James Patterson was surrounded by believers. The ad executive turned author had sub-par success with his debut novel The Thomas Berryman. While it had won the prestigious Edgar Award, it only sold 10K copies—a paltry sum. For his new book, a mass-market thriller entitled Along Came a Spider, Patterson wanted to do something different. He wanted to go directly to consumers with television advertisements. At the time, this just wasn’t something that was done! It was expensive and the publisher didn’t want to do it. Popular thought was that books were a higher medium, an art above: consumers wouldn’t want it being pitched to them on their TV.

Patterson said, “fine I’ll do it myself” and shot the commercial on his own dime. The publisher saw and agreed to share the cost to show the ad in 3 markets. Despite the skepticism, the move worked. The book debuted at #9 on the New York Times bestseller list, eventually making its way to number 2 in the paperbacks. The book now has over 5M copies in print and is Patterson’s most successful work to date. More impressively, this move launched one of the most fiscally successful careers in the history of literature. Some estimates pin his yearly income at $90M+ and he publishes over 6 books a year.

Patterson’s books are almost universally criticized. The prose is basic to the point of stupid, the plots contrived and gratuitously violent, and Patterson doesn’t even write the things himself. He simply makes an outline and lets the coauthor take it from there. Nevertheless, he makes bank. I love this story because however you feel about his work (to be clear, I hate it) you have to admire Patterson’s shrewdness. He played a different game than other authors. Rather than rely on the stamp of approval from elite media publications’ book reviews, he used mass appeal to accomplish his goals.

Whether you’re looking to sharpen your finance skills or start from scratch, Maven’s selection of finance programs has everything you need to invest like a pro, from Financial Statements courses to FP&A / Cap Table Management.

The biggest takeaway from Patterson’s continued success is that he understands what he has. He isn’t creating art. He isn’t creating something to elevate the world’s consciousness, he has a product and he is willing to sell the hell out of it. His initial commercial success completely alters what he now creates. He recognizes that most people wanted contrived, easy-to-digest plots, and they want as many of them as possible. Ultimately, economic incentives have become totally inseparable from the art that is being created. I would argue that the market is the message. Market dynamics (such as the advertising channels that drive sales) determine what kind of content is being created.

Just as Patterson first embraced TV as a marketing channel, writers are embracing new technologies to differentiate their products. This time around its not just acquisition. It is co-creation with artificial intelligence, it is going multi-product with Spotify, it is using TikTok to fill the top of the funnel. No part of the market is ever going to be the same.

When a market changes like this there are serious fiscal rewards to be had; lots of people will make lots of money. That’s great and I support people trying to secure the bag. However, I think we don’t understand what the downstream effects will be on art, on literature, and on knowledge itself. We may end up in a much worse spot.

Writing’s Atomic Unit

Last week I argued that you could break down the core activity of any business into three buckets: Creation, Acquisition, and Distribution. In the pre-internet days, it looked something like this:

- Creation: A writer would gaze upon their muse, lick their pen, and set to work creating the next great epic. Their agent and publisher would cheer them on.

- Acquisition: Advanced copies would be sent to reviewers. Some form of marketing campaign would be run, and all of this would be coordinated by the publishing house.

- Distribution: Books would be placed on bookshelves across the country. The authors with the best track record or with the most powerful agents would secure more prominent shelf placement.

All along the way there were gatekeepers who determined what content was successful or not. These gatekeepers were individuals with Ivy League degrees and “refined taste”.

I want to be clear: this wasn’t some magical time for literature. Female and minority voices were consistently denied a platform. Books were non-competitive products that slowly lost market share to other entertainment offerings. And there isn’t something inherently wrong with mass-appeal, easy-to-digest formats. Charles Dickens, author of Oliver Twist and Great Expectations, used the serial novel format to publish bite-sized pieces of his books. Serials were a great way to make money so that’s the format he used to write some of the greatest works of English literature. Economics and the technology of the printing press determined his format and his writing style. It wasn’t solely some sort of artistic sense. Again, this was just the way things were.

Distribution

If we come back to the present, everything changed yet again with the internet. Distribution was no longer reliant on getting on the right bookshelves or catalogs. The way to win was to be the first to surface in Amazon’s search bar. It was the long tail that won. In fact, at one point in Amazon’s history, a quarter of Amazon’s book sales came from outside the top 100K titles. Ecommerce dramatically brought down the importance of bookstores but the Kindle launch in 2007 made things even more complicated. Suddenly distribution costs truly were zero. Authors could only compete on their acquisition method or on their content. It diminished the role of publishers and by 2013, ¼ of book sales on the Kindle were from independent authors.

Naturally, this also changed the format and style of books being published. Mystery, fantasy, and romance novels took off. Writing became more simplistic as indie authors churned out as many books as possible to keep their fan base engaged (sound familiar? say Patterson-esque?).

So distribution has been changing since 1994. What’s new on the acquisition and creation side?

Acquisition

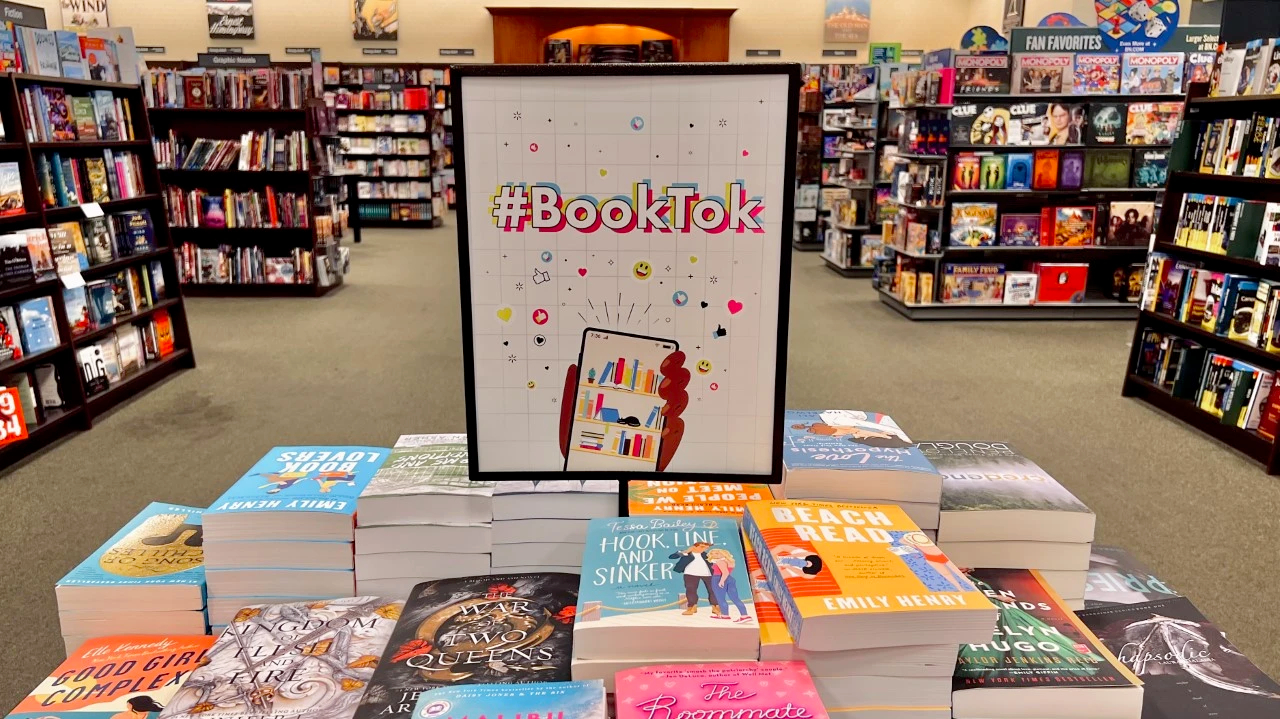

Let’s say that you are looking for a new book to read. You may ask your friends or peruse their GoodReads accounts. Maybe you look for social proof from a creator you enjoy (shout out Oprah's Book Club). My personal favorite method is to just wander around a bookstore to just grab whatever catches my eye. If you were to do the Napkin Math recommended method of meandering at a Barnes and Noble near you, you’ll almost certainly see a sign like this:

#BookTok is one of the most popular communities on TikTok with over 77B views globally. In it, people will talk about “are you looking for a grim-dark, underwater, murder mystery with an LGBTQ character? Do I have something for you!” Because TikTok’s recommendation algorithm is so good, the books tend to do well. It has gotten to the point that retailers like Barnes and Noble have press releases about it and Indigo (a Canadian bookseller) even mentioned the power of BookTok on their earnings call. Again, this is wonderful, in particular for the authors, that we are selling more books. However, none of this is James Joyce. We aren’t pushing people’s intellects here. They are mostly candy books, rotten for the mind when consumed in large quantities.

If we have learned anything from constructing algorithmic recommendation feeds over the last 10 years of consumer internet, it is that the content sludge becomes the most popular. It's soft-porn and zit videos and Marvel and reality TV that trends. None of these things are inherently harmful when consumed in reasonable quantities. But when every category of content is economically incentivized to make stuff that performs well with the algorithm, monetary gravity pulls us towards sludge. It is the Pattersonification of everything. Some higher forms of art will still break through, but the statistical average is shifting towards stupid.

It's important to point out that it isn’t just TikTok that is algorithmically funneling people towards books. There is a thriving books scenes on Youtube, Tumblr, Twitter, and really every attention platform. The important thing is that the holders of the keys of consumer attention have shifted from the New York Times and Oprah’s book club—it is now the algorithms. We are not at the point where the powers of old are gone, they still hold some sway! But the power dynamic has completely shifted. To be a successful author means writing the kind of book people want to share within the context of the internet.

Creation

Tech has worked itself backward from distribution and is now fundamentally altering how writing is done. It is doing it both in subject and style as we have discussed, but also in what an author even is.

One of the more fascinating examples of this phenomena is Sudowrite. They utilize OpenAIs GPT-3 model to allow fiction writers to generate new prose. Want to “show, don’t tell” there is a magic button for that. It isn’t at the point where it can write entire chapters itself, but it is still powerful. From a Verge article about an indie author who utilized the tool,

“Lepp soon fell into a rhythm with the AI. She would sketch an outline of a scene, press expand, and let the program do the writing. She would then edit the output, paste it back into Sudowrite, and prompt the AI to continue. If it started to veer in a direction she didn’t like, she nudged it back by writing a few sentences and setting it loose again. She found that she no longer needed to work in complete silence and solitude. Even better, she was actually ahead of schedule. Her production had increased 23.1 percent. [Emphasis added]”

At first this sounds great! An author is able to write more and be less stressed by the labor. However, the downstream effects of the distribution changes we’ve discussed soon reared their ugly head. From the same article:

“With the help of the program, she recently ramped up production yet again. She is now writing two series simultaneously…It was an expansion she felt she had to make just to stay in place. With an increasing share of her profits going back to Amazon in the form of advertising, she needed to stand out amid increasing competition. Instead of six books a year, her revised spreadsheet forecasts 10.”

There are similar tools to Sudowrite for every manner of writing—no content job is truly safe. Note: In 10 years will I look at this post as the obituary of my career? Regardless of genre, most of these tools are powered using GPT-3 from OpenAI. It is an open secret that GPT-4 is in the works and will be much more powerful than the version that most companies are using so we can expect further improvements soon.

Can you imagine this in 7-10 years? I wonder if it will be so powerful that all authors will be pulling a Patterson. Simply type out a rough outline and the AI coauthor does the rest. Really, there is a non-trivial chance that we are at the end of writing as we have known it. Soon it will be mega-prolific authors, with carefully tuned TikTok plots, planting ads all over attention aggregators like Amazon who are the winners. The skill of being an author will shift from being purely of prose and story to those who can utilize technology and marketing most effectively. Maybe authors will layer in additional media products like podcasts? Or maybe gaming or art or community or something else entirely? All I know is that it won’t just be the book anymore.

In all honesty, I don’t know how to feel about any of this. I am keenly aware that every previous innovation in media has been met with cries of how it is the end of the arts. For the most part, technology has democratized creativity and allowed more total volume of people to be artists, not less. Whether these tools are net good for us all or not, they likely spell doom for the writer archetype of yesteryear. It’ll be someone who runs a YouTube channel updating readers on their progress, has TikToks about a day in their life going viral, and uses AI to fill out prose who will be the bestsellers. There are some authors today who are doing versions of this path today and still producing meaningful work (Brandon Sanderson is my personal favorite) but it still feels like the sludge novel will win out. Be prepared.

This cover image was prepared using Midjourney: prompt "a robot writing a book, 8k, unreal enginge --upbeta"

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!