Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

In a recent interview, Mark Zuckerberg said something remarkable: “Feeds [were] friend content and now it’s largely creators, and in the future a lot of it is going to be AI-generated.” [Emphasis added]

Consider what he is saying. Not only will Meta’s curation on feeds like Instagram and Facebook be entirely algorithmic, but the content will largely be produced by algorithms, too. No longer will there be middlemen—your aunt, a friend from high school, or a Taylor Swift fan account—that you are responding to. Instead, you’ll be interacting directly with machines. This is a remarkable idea offered up by the best positioned person in the world to have it. Curation and creation, all algorithmically controlled.

However, Zuckerberg got one thing wrong: It isn’t the future—it's already happening. A cottage industry of AI creators on social media is flooding the internet with their creations. My research indicates this phenomenon is already far larger than you think.

Across X, Facebook, and other social media platforms, AI content is generating tens of millions of impressions every week. A Europol study estimated that 90 percent of online content will be “synthetic”—a.k.a. AI-generated—by the end of 2026. These estimates strike me as accurate, if not a little conservative. The cost to generate text and images is already so low that human creators can’t compete. Whether you like it or not, AI products are vying for our attention.

In this column, we’ve discussed ad nauseum that attention is a competitive marketplace, meaning that AI content is only a threat if it is more attention-gaining than other assets, or if the producers of AI content have a structural cost advantage over traditional media companies.

This article is not a doom-and-gloom outlook on AI-created material. Crucially, AI-generated content is only performative online if it is more competitive—if its consumers derive superior utility from it. It only takes market share if people like it. While it is tempting to dismiss this content out of hand, those impressions are earned, not given. Attention aggregators like the social media platforms are not in the business of losing users, so they aren’t going to surface something that isn’t performative.

Why are we talking about this now? AI content—in particular, AI-generated images—are, as of last week, indistinguishable from real photos. Welcome to the season of AI slop.

Checking in on AI progress

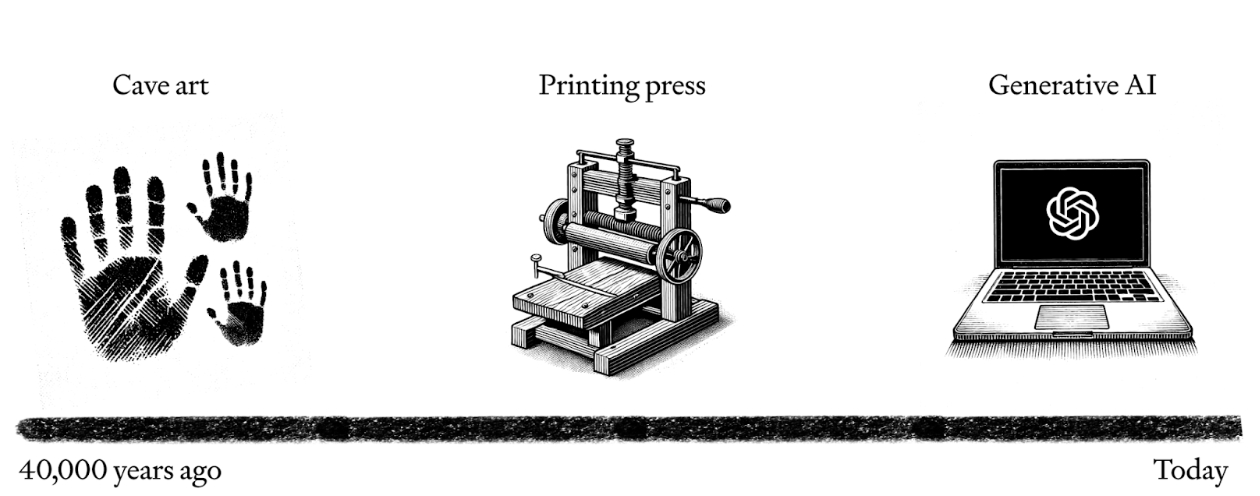

Let’s put content—a horribly vague word, but the only one broad enough to encompass my argument—on a timeline of improvement. On the left-hand side is the cave art of 40,000-plus years ago. It is creation at its most primitive, with humans using simplistic tools to express themselves. Each subsequent technological improvement like the Gutenberg printing press decreased the costs of creation or gave individuals the power to make more sophisticated art. Progressing from the harpsichord to the digital piano allowed far more people to play the keys. Progressing from the Gutenberg printing press to Google Docs and Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing allowed far more people to publish books.

Source: Every Illustration.

AI-generated content is the latest iteration of that improvement curve. It allows people to transform a hastily scrawled prompt, and voilà—you can produce not just one object, but thousands. It is the next step in that improvement curve, allowing more people to create more content cheaper. This improvement curve is why AI generation startups like Runway describe themselves as a “new type of camera.” Not only can you make videos, you can make new kinds of films (for a lot less money), too.

The key to being a substitutable good, is, well, being able to substitute what came before it. For AI-generated content, that means it can look like the content produced by tools from previous generations.

As of last week, we have officially passed the point where it is possible to tell the difference between AI images and real life without close examination.

Source: Reddit.

This was made possible with the release of open-source models—known as Flux—made by Black Forest Labs, some of the original team behind Stable Diffusion (for which it raised $31 million). From there, people fine-tuned the models to be more realistic with a modification called LoRa. Because the Flux model and LoRa fine-tune are open-source, you can’t put the cat back into the bag. Anyone can do this now! And it will only get better as other developers work on it.

Here is an image, pre-LoRa, using Flux out of the box.

Source: Reddit.

Here is an image after using LoRa.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

I'm not sure you are using the word performative correctly.

"While Meta and X should be concerned about truth, it is so hard to define and enforce that they end up focusing on the much easier and more legible thing—profit. Because the primary usage of these platforms is distraction and entertainment, truth is secondary."

Is *that* the reason they end up focusing on profit - because truth is too hard? I doubt it. If truth were most profitable, they would focus on and favor truth. And doing so is one of the few competitive advantages I can imagine a future new platform using with any chance of success. If a social media platform came out tomorrow that could demonstrate strong capability in detecting, flagging, and actively filtering (or outright rejecting) fake content I would move there pretty quickly.

Instead comments and decisions like those from Zuckerberg, that have already turned the Facebook feed into a stream of mindless crap (instead of the human connections I joined for in the first place) incentivized me to start my own, private social media site. Most people won't have the means, but not everyone has to. This may lead to a fragmented future...

I love how you write!

"Before our tiniest human beings are even fully capable of stringing together sentences, they can form emotional reactions to the content they view. Our lizard brains all like the same thing—and apparently that thing is dirty yellow buses."

"That the subject matter is consistently performative suggests that AI content is a substitutable good in terms of the reactions it elicits from consumers. Additionally, the workflow for these AI creators is identical to that of an employee at any other media company: Make something, distribute it through your favorite channels, get paid, and repeat. The fact that the object was created with AI doesn’t change its position in the feed, only the consumer interest."

On the topic of viewing AI-generated content:

You're not wrong—I’ve caught myself watching, listening to, and viewing AI-generated content. I don't particularly find it off-putting, unless it's done poorly or I feel a bit cheated because it seemed so real. But then again, the same goes for regular content, I suppose.

You make a valid point about traditional media needing to adapt. In a way, the money flows upstream to the platforms that stand to profit from a massive wave of creators who couldn't produce content before the rise of AI.

But on the flip side, with the increase in model capabilities, it's time to make the memes of my dreams!