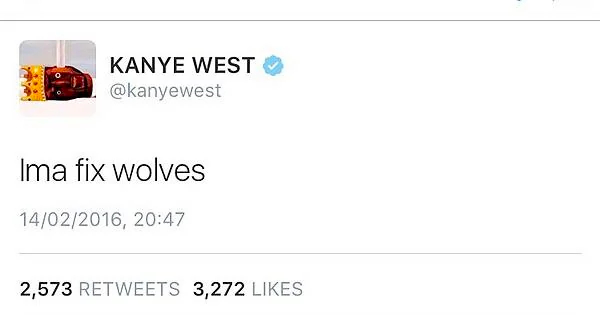

Author’s note: In 2016, Kanye West released his seventh studio album, The Life of Pablo. The record was a mess. Tracks were disjointed. The production value on some tracks had soaring grandeur, while others were clearly unfinished. In response, West called the album a “living breathing changing creative expression.” He tweeted:

I’ve often reflected back on this moment. To me, it was the biggest and loudest shift in what content is. The internet changes the materiality and meaning of creation. In previous eras of music, the record was literally that: a record. With the internet, the album is an updatable hyperlink. Four months after the album’s release, West added an additional track. In an interview with GQ in 2020, West was dismissive of the critics saying he should leave the album alone, telling the magazine, “Nothing is ever done.”

This essay is my attempt to treat my work in the same way as West. What would happen if I constantly rewrote or re-examined my previous ideas? I published v1 of this essay a year ago and have been dissatisfied with it ever since. Today’s post is v2. Ima fix wolves.

In a bedroom with no TV, no AC, one window, and zero forms of entertainment, I lay back and contemplated the best use of my free time. It was the summer of 2016, and I was living in the hills of Oakland. My biggest constraint was that I had almost no money. Going to In-n-Out was a special treat. Most days the only meal I could afford was the free cereal at work.

As I sat alone in this hotbox of sweat and misery, I sketched out a formula for how I could most effectively use what little money I had to entertain myself. It came out like this:

Hours of entertainment / total cost = unique distraction units (UDU)

My goal was to figure out how to squeeze the most value from every dollar. A videogame that costs $60 and takes 60 hours to complete yields a distraction value score of 1. A movie in theaters is a much worse deal: it costs $20 and provides 2 hours of entertainment, yielding a UDU score of 0.1.

However, not all hours of entertainment are created equal. So I took the formula a step further—connecting the UDU to the utility gained.

UDU x utility gained = total entertainment value (TEV)

An audiobook that is 60 hours long, costs $12, and yields a personal 30 utility units results in a total entertainment value of 150. It seemed simple: I just had to run the algorithm over and over again, comparing TEV scores, and then pick the activity with the highest score that I could afford.

But I soon ran into a problem—my results were wildly inconsistent. Some days, when I was gassed up, the gym would pull a 100-plus TEV. On other days, when my body was composed purely of garlic mashed potatoes, the gym might have a TEV of 5.

My personal utility was all over the place. The value of an activity was entirely dependent on my mood for the day.

In neoclassical economics, the definition of utility is roughly “the value or enjoyment gained by consuming a good or service.” The core assumption at the heart of that definition is that consumers are rational and maximize their available utility. This idea only makes sense to people who spend very little time in the real world.

I didn’t follow this definition—I wasn’t even in the same ballpark. The rational thing was to figure out my TEV and stick to a consistent pattern of long-term utility maximization. I should finish the summer with glistening abs and a freshly annotated copy of War and Peace.

Instead, I spent most of those months depressed, watching reruns of The Office. Why? Why couldn’t I be better? The rational analyst in me was frustrated to no end. My formula and logic were sound, so why couldn’t I force myself to follow them? Why couldn’t I behave like a rational, utility-maximizing individual? Instead, I picked activities that were short-term utility-maximizing and long-term bad.

Why people make stupid, self-destructive choices is something that nearly every philosopher since Aristotle has wrestled with. So far, there hasn’t been a convincing answer. Our modern scientific institutions have also failed to come up with one.

The sociologists following the tracts of Weber would say that humans are unable to behave rationally because of social structures. Psychologists may blame individual temperament or mental barriers. Neoclassical economists would ignore me, write abstract mathematics to confuse the laymen, and tell me to pull myself up by my bootstraps.

That formula, created seven years ago, has become so important to me because it represented a moment of personal reckoning. Despite how desperately I wished for it, no matter how much I prayed for it, I could never make myself truly utility-maximizing. There was always something that got in the way of making the right choice. In the pursuit of utility maximization, I ended up making my life more miserable. The pursuit of the best killed my ability to do the good enough.

The futility of utility maximization became an intellectual earworm. The more I looked outside myself, the more I saw the phenomenon occurring. At work, at home, in politics, everywhere the pursuit of great killed the good. And if I couldn’t stop myself from just watching The Office, you can imagine how troublesome utility maximization gets at the scale of companies.

Good people, bad executives

I kicked off an essay about Spotify with this anecdote:

“Within 24 hours of employment at Pandora Radio, I knew the company was destined for doom. It was my first internship in the Bay Area, in 2016, with a role on the corporate strategy team. At the time, executives would stride around the office, lauding Pandora’s superior music recommendation capabilities and long-time leadership in the space. There was some panic over Spotify, but Pandora felt it could respond well. However, as [I] walked over to [my] desk, [I] saw a C-suite executive happily bopping his head, Spotify’s desktop app open on his computer. When [I]later asked that executive why he was on Spotify, he responded simply, ‘It is more convenient.’”

Obviously, the Spotify threat should’ve been taken more seriously when Pandora’s own executives preferred the service. And to be fair, there were many serious discussions about how to respond. The highest utility choice for the company would have been to crush the Swedish upstart. However, the highest utility choice for most individuals at the company was to do nothing. It was easier to continue to slowly lose market share rather than go out into the intellectual and financial wilderness required to reinvent the company. There was a mismatch between what the executives wanted (to protect their jobs and lifestyles) and what the company wanted (to do anything but be acquired by SiriusXM).

This pattern of employees helping themselves over the company is fairly understood (and is something I’m actually in favor of in some circumstances). But I’ve also seen good ideas dismissed because of a founder’s pride, managers fired because their talent threatened the person above them, and employees self-sabotaging their careers with stupidity. Everywhere, at every level, organizations and individuals lose their minds and pick not just the irrational thing, but maybe the most harmful choice possible.

Just as academia has continually tried to explain personal utility maximization, scholars of business have been attempting to do the same for organizations. There are dozens of frameworks and crackpot theories to solve this problem: objective, key result. Key performance indicators. Directly accountable individual. Good to Great. The list goes on. All of these methods hold some measure of truth—I’ve seen them work well. But I’ve also seen them destroy companies. There is no universally true framework.

We as a society (and as individuals) seem to be unable to get utility right, whether the stakes are one intern’s entertainment budget or the future of multi-billion-dollar companies. Even in the most dire of circumstances, in literal life or death situations, I’ve witnessed people’s utility maximization fail.

Utility’s impossibility

Some of the toughest lessons of my life occurred when I was a Mormon missionary. Growing up as a middle-class white guy in rural Minnesota, I was completely sheltered from the hardships of the world. On my first day wearing the white shirt, tie, and bike helmet of missionary-hood , I helped a woman, her face purple and blotchy with bruises, hide from her boyfriend. Another woman, with hungry desperation in her eyes and track marks running up her arm, grabbed my arm and begged for money. I still see those desperate faces in my dreams sometimes. It was a wake-up call to how bad life could get for 19-year-old Evan.

Happiness is unfairly, and seemingly arbitrarily, distributed. Some people were unable to free themselves from drugs, from abusive partners, from poverty, despite years of effort. Others were the opposite: one person I was teaching quit crystal meth cold turkey and was fine. Even in the most dire of circumstances, the ability to be a utility-maximizing being appeared to be randomly gifted.

Since that summer in Oakland, I’ve kept looking for the theory that would explain why some people do the right thing for themselves and others don’t. Some universal truth to illuminate the murky depths of the human condition.

Sometimes I think the sociologists got it right, and we are mostly products of our environments. (Maybe I believe this to justify my bachelor's degree in sociology.) At other points, I think the neoclassical economists’ wacky algorithms of rationality are right. In some of my more reflective moods, I turn to the balm of spirituality and divine intervention. None of these answers have ever fully, truly satisfied me.

That formula, constructed in the bleary haze of a Bay Area summer, was so important to me not because it was useful, but because it was useless.

My silly hope to come up with a formula to tell me what to do was an analyst’s pathetic articulation of the futility of universal evaluation mechanisms. Our goal as individuals should probably be to become more rational and rigorous. We shouldn’t jump blindly into major decisions. However, in our desperation to find the perfect choice, we often sacrifice the one that gets us close enough.

Nine years ago I attended a Q&A with Mitt Romney. By all accounts, he has achieved the height of personal utility maximization: a beautiful family that loves him, a wildly successful career in business, meaningful religious service, and, as he put it, he “got second place in the presidential race.”

One audience member asked, “What was your plan to get where you are? How did you do it?”

His answer, given with a chuckle and a wry grin, surprised us all. “I didn’t have a plan at all. I just knew which direction I wanted to run and I sprinted toward it all my life.”

I wish when I was a missionary I had focused less on converting and more on helping. I wish when I was at my previous startups I had focused more on building and less on winning. Sure, I may not have done exactly what I had thought I wanted, but finding ways to love the process would’ve allowed for better outcomes anyway. What we want is such an abstract idea, built on a foundation of shifting sand, that it is pointless to try to pick the optimal path to achieve it.

It is in the acknowledgement that we don’t know how any of this works that we can find comfort in doing things our own way—which, wonderfully, is the only way to achieve differentiated outcomes anyway. By not worrying about the details or the distant future, and instead focusing on how we can live our best daily lives, we will be successful. Just pick a direction, and run.

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Another strong article and timely antidote to the one posted earlier in the week about business physics which didn’t sit right for the reasons stated in this one (to be fair I didn’t read it all)