It’s astonishing just how much of human behavior can be ultimately traced back to somebody trying to increase the valuation of something.

When we see huge corporations like Facebook—I’m not ready to call them “Meta” yet 😅—marshal incomprehensible resources towards making ideas like “the metaverse” happen, that’s about valuation. When NFT collectors flock to projects that show signs of breaking out, that’s about valuation. When Twitter finally starts launching new features, or when an oil company wants to build a new pipeline, or when a local homeowner complains to their elected officials to stop a new apartment building from being built around the corner, these actions are all about valuation, too.

So much of the world revolves around valuation because valuation is the source of wealth. Valuation is why we have billionaires. Elon Musk’s $316,000,000,000 hasn’t come from his salary. Valuations are also how you can get headlines of billionaires “losing” hundreds of millions of dollars in one day (or vice versa). That money isn’t leaving a bank account, it vanishes as the value of the boxes these billionaires are investing in fluctuates.

The question is: where do valuations come from? Why are some assets considered more valuable than others? How do businesses, commodities, land, NFTs, options, derivatives, and currencies (crypto or otherwise) get reduced to a number?

There are a number of ways to answer this question. For instance, one way to learn how valuations are set is to learn how market-making mechanisms bring people with different opinions and incentives together to find a single “market price.” Another way is to understand how each individual in a market subjectively determines their own opinion about what an asset is worth. Although the price-finding mechanism of markets is fascinating to me, as an entrepreneur and investor I find the latter question to be more practical. And I am mostly interested in valuation of businesses, as opposed to other types of assets listed above. So this post is going to focus on how individuals can decide what they think a business is worth.

Business valuation is often treated as some sort of mystical black art. Especially in 2021, with valuations across the board going seemingly wild, it’s helpful to ground yourself in the fundamentals. That’s not to say we’re taking a conservative approach to valuation—you may well use the tools from this post to estimate sky-high valuations are actually a steal. Our goal isn’t to persuade you what you think the value of a thing should be. Instead, we’ll cover the basics of valuation methodology so you can understand it at a deeply intuitive level.

Let’s dive in!

Valuation and Cash Flow

Valuation is how much someone is willing to pay to own a piece of a business.

It may seem obvious, but it’s worth asking: why would anyone spend money to own some percentage of a business? What’s the “job to be done” of business ownership?

The two most common reasons are:

- To make money. This can happen either through dividends, where the company distributes profits to owners, or by selling the stock later for a higher price than you paid to buy it.

- To control the business. (Requires a majority ownership.) When you control a business, you can use it for all sorts of things. For example, if you control two businesses that complement each other, you can merge them together in a way that makes both businesses even more valuable than the sum of the parts. (Synergy!) Or maybe you just want to eliminate a competitor. Or maybe you’re just a fan of the business and want to be involved and get to call the shots, like sports team owners.

Of course, there are other reasons, like you might want to support the business if someone you care about runs it, or you believe in the positive impact the business could have on the world. But those typically need to be mixed in with the two above in order for someone to invest any substantial sum.

Since the value of controlling a business’s operations is pretty idiosyncratic to each specific situation, this guide will focus on the first point: making money.

To understand how investors decide how much they’re willing to pay to own a business if they’re not making a bid at control and just want to get a good return on their investment, it helps to eliminate all the complicated nuances of actual businesses and think of them as simple black boxes.

The Black Box Metaphor

Think of a company as a little black box that spits out cash. Say one particular black box has been printing $5k each month for the last two years. It literally just connects to your bank account and adds $5k every month on the 1st.

How much would you pay to own that box?

To come up with a number, you might want to know the answers to a few questions:

- How certain is it that the box will continue to print $5k each month?

- How long has it been printing money?

- Did it start out printing $5k a month? Or did it gradually grow to get there?

- Is it still growing? Could it print out more than $5k/mo in the future?

- How many other people are trying to buy the box?

- What is the mechanism by which the box generates the $5k? How does it work?

- Do you have to do anything to keep the box functioning properly?

These are the same questions all investors—from VCs to BlackRock to Robinhood meme traders—are trying to answer when considering an investment. But I like the “black box” metaphor because it takes the complicated, abstract world of financial considerations and makes it extremely concrete and relatable. It forces you to think about the nature of cash flows, and it helps you understand why people ultimately buy stocks.

The terminal value for any business comes back to cash returned to shareholders in the form of dividends. When you buy AT&T, 8% of the value of your stock gets paid back to you every year. It only takes 12 years to earn the entire value of your stock back in dividend payments—and even then you still own the stock and can keep collecting dividends or sell it! The dividend is the “printing cash” function of the black box.

Now, many astute readers may be thinking, “But the fastest-growing and most popular stocks don’t pay dividends.” And it’s true, they don’t. But the reason people buy them today is still ultimately connected to the fact that they will probably pay dividends one day in the future.

To understand why, let’s return to the black box metaphor. Imagine you buy the box and you have the option to put money back into the machine, which, if you do it right, will improve the box’s functionality and enable it to spit out even more cash later. If you think you can do this you probably should, for two reasons. First, every time the business sends money to your bank account you get taxed on it. Second, when you reinvest profits back into a business productively, it can compound over time to create exponential growth. Which is great! But growing profits only matters if you eventually either start using those profits to pay yourself, or sell to someone else (who is buying because they might use those profits to start paying themselves).

The backstop of being able to actually earn income directly from owning a business is part of what supports stock prices. Some might call it “intrinsic value.” Even if every investor in the world decides they don’t like Facebook anymore, as long as it’s printing cash there’s a pretty concrete reason to buy it that doesn’t depend on investor opinion. This is why some people are worried about the long-term price of cryptocurrencies and NFTs, since in most cases there is no cash flow and therefore no dividend. (Although with NFTs specifically and smart contracts generally dividends are totally possible.)

The black box metaphor also helps us understand the importance of strategy. In the real world each business is a complex organism in an economic ecosystem. Survival is anything but guaranteed. Those who understand the lay of the land and how things work (a.k.a. business strategy) will do a better job picking businesses that are likely to keep printing lots of cash over time.

And in fact the length of time you expect the cash will continue flowing is a surprisingly central component of valuation.

Discounted Cash Flows

The gold standard for determining the value of a business is a method called “discounted cash flows” (DCF).

There are two steps to running a DCF analysis:

- Estimate the future cash flows you expect from the business—i.e. how much money you expect the business to make each year in the future.

- Discount those estimated cash flows to their net present value.

(If you don’t know about net present value, this explainer is good, but the basic idea is money is worth more to you now than later because if you had it now you could invest it and it would become worth more later. So when you’re estimating the present value of the cash a business will spit out 10 years from now, you need to first figure out how much cash it might be, then discount it because 10 years is a long time from now.)

Ok, let’s go over each step in turn.

Estimating Future Cash Flows

This is the hard part. The future is uncertain and nobody, not even the Oracle of Omaha, knows for sure how much money a business will make in the future. It’s challenging even with stable companies that have been around a long time like Coca-Cola, and it’s damn near impossible with new startups.

So should we throw our hands up and give up on trying? I wouldn’t advise it. I find it useful to take vague feelings about how big I think a business could be in the future, and attempt to quantify it. Even though your analysis will be imperfect, modeling a business can help you uncover hidden assumptions and understand the mechanics of how it might grow more deeply.

For instance, let’s say we want to create a model that will help us predict Apple’s future cash flows. The first thing we’d want to do is understand all the most important sources of revenue for Apple and how they’ve changed over time. Some of this data is broken out publicly, but other data needs to be inferred from original research. This is why hedge funds and investment banks pay huge sums to commission original reports on important questions like market share (to predict market power), costs of various components needed to run the business (to predict costs), happiness of existing customers (to predict retention), etc.

It’s like a detective game where you have millions of dollars on the line. All this intelligence then gets fed into a model of the business that basically teases apart the various lines of business and how well they might perform in the future.

But even if you do your homework and create a good model to extrapolate a business’s current cash flows into the future, you might notice there’s one thing missing: new lines of business. For example, what if Apple builds a VR/AR headset? Or a car? How would that impact their future cash flows? How can you make an estimate when there is no historical data to go on? This is obviously difficult, but it’s also an opportunity. If you can uncover a unique insight that makes you confident that Apple’s VR business is going to be huge before other people believe it—before it gets “priced in” to the stock price—and if you end up being right, then that’s how you make money as an investor.

This is one reason it’s so valuable to understand the principles of business strategy. When asking yourself how much cash Apple will generate in the VR business, it’s useful to know about things like “economies of scale” and “network effects” so that you can model the competitive threat posed by other companies, like Facebook / Meta.

But predicting the success or failure of new lines of business isn’t the only way that knowledge of strategy translates into valuation skills. It’s also helpful if you want to understand how durable a business’s cash flows are. The reason some cash flows grow faster than others, or stick around longer, is because they are more strategically robust—i.e. less likely to crumble in the face of competition. As legendary VC Bill Gurley once said, “all revenue is not created equal.”

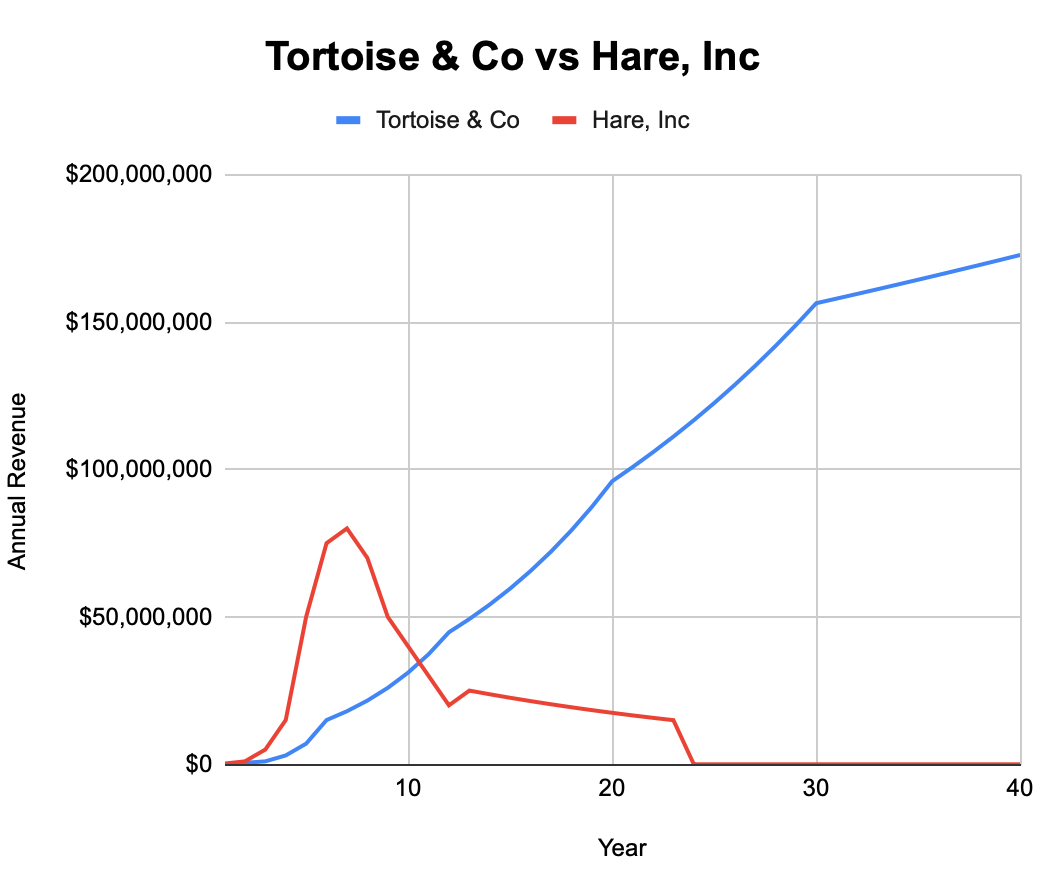

To illustrate just how much this matters for the purposes of valuation, let’s look at two imaginary companies: Tortoise & Co, and Hare, Inc.

Discounting Future Cash Flows

Tortoise & Co may not seem flashy at first, especially compared to it’s faster-growing friend, Hare, Inc. But don’t be fooled by the slow start—owning a piece of Tortoise & Co is a great long-term bet.

Here’s a chart depicting each business’s annual revenue from inception to year 40:

(If you’re curious, here’s the spreadsheet I used for this.)

The Hare gets off to a fast start, as is its nature, but ultimately runs out of steam, slogs along for a decade or two as a shadow of its former self, and then shuts down.

The Tortoise on the other hand has an extremely robust business model. The flywheel of the Tortoise takes longer to get going, but once running is extremely durable.

The thing is, most of Tortoise & Co’s future revenue will only come to fruition in the distant future. And as we said earlier, money in the future is worth less than money today, even in the unrealistic assumption that your model is 100% correct and has zero risk or uncertainty. This is because of the time value of money: if you had the cash today you could invest it and it would grow and be worth more in the future. In other words, using a discount rate is basically factoring in the opportunity cost of an investment.

So maybe Tortoise & Co isn’t such an obvious bet after all? I mean, who wants to wait two decades for substantial cash flows? Luckily we have a way to directly compare the present value of these two cash flows. This is where we do the “discounting” step of the “discounted cash flow” analysis.

To estimate how much cash 10 years from now is worth to you today, you need to know how much return you could get in 10 years if you invested that cash today. This is an impossible question to answer, because there are unlimited ways to invest money and nearly unlimited possible returns. But just because it’s impossible to answer doesn’t mean we can’t have a useful ballpark estimate.

So let’s pick 8%, because that’s what the S&P 500 has averaged since 1957. By picking this as our discount rate, we’re essentially saying: “how much more money would I make on this investment than if I invested in the S&P 500, assuming it continues to average the same returns.” Of course there are other ways to use the discount rate. You could pick a lower discount rate because you are confident in the investment and think it’s a safer bet than the S&P. Or you could pick a higher discount rate because you think the investment is more risky than the S&P. For more nuance on the discount rate, this is a good guide, but for now let’s stick with 8%.

Here’s how we run the numbers.

For each year in the future:

- Take the revenue from that year

- Subtract the amount our hypothetical S&P 500 investment would have earned by then

Here’s the typical equation most people use to do that:

Discounted Value of Year N Cash = (Year N Cash) / ((1 + Discount Rate) ^ N)

Let’s plug in some specific numbers as a concrete example. Let’s say in year 3, Tortoise & Co is estimated to earn $1m. Here’s what the equation should look like:

$1m / (1 + 0.08)^3

Which can be simplified and solved as:

$1m / 1.26 = $793,650

In other words, given an 8% discount rate, $1m in three years is worth $793,650 today.

Ok! So we know how to get the present value of one specific future year’s worth of cash flows. Let’s now extrapolate that to the entire projected future of the cash flows for Tortoise & Co and Hare, Inc.

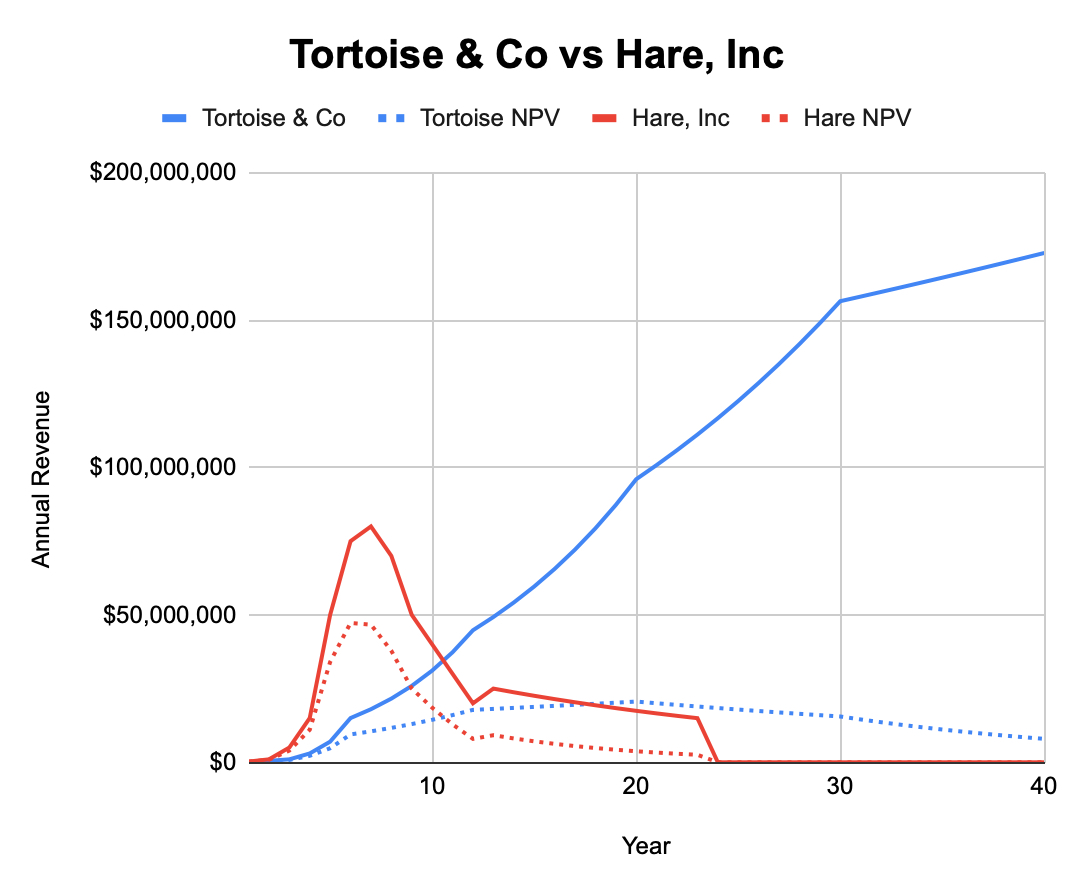

Here we have the same revenue graph as above, but with dotted lines for each company representing the value of that future cash flow. You’ll notice that in the early years the dotted lines are close to the solid lines, because our hypothetical S&P 500 investment hasn’t had much time to compound. But in the later years the dotted line gets closer and closer to zero.

When calculating this number in the real world, most people don’t project 40 years out. It’s just too hard to estimate cash flows that far into the future. But it’s entirely possible, likely even, that stable businesses could last that long. Just look at the history of companies like GE, IBM, GM, Ford, P&G, Coca-Cola, etc. It’s definitely possible that today’s tech giants will have similar longevity. So to get around this, people use what’s called a “terminal value” where they essentially pick a fixed growth rate that’s conservative (somewhere around the inflation rate and overall GDP growth rate) and just assume the company will keep growing at that rate forever.

There’s just one last step before we can know what our DCF analysis tells us this company is worth: add the net present value of all the future cash flows together. Basically we’re summing the Y-values of the dotted lines at each point along the X-axis.

When we do that, here’s what we get for each company:

- Tortoise & Co: $542,266,066

- Hare, Inc: $303,960,469

So there you have it! If our estimated cash flows and discount rates are correct, the Tortoise is worth $239m more than the Hare.

This is the ideal, “correct” way to decide how much you think a company is worth. It’s considered ideal by many in finance because it is based on how much money the company will make in the future, rather than people’s opinions about how much money the company will make. The goal of investing using this analysis is to find companies where the value outputted by your DCF analysis is greater than their current market valuation. Plus perhaps a “margin of safety” just in case you’re wrong.

Of course, just because DCF analysis is “ideal” doesn’t mean that’s actually what happens…

Why Everything is Dumb Right Now

Matt Levine, a finance columnist for Bloomberg, opened his weekly newsletter with this gem today:

The basic issue is that right now everything is dumb. You can complain about that, or you can embrace it. In investing in 2021, “my channel checks and fundamental modeling suggest that this company will grow earnings faster than the market expects so I will buy it with a price target 20% above today’s price” might sound smarter than “this company’s chief executive officer just tweeted a picture of a dog at Elon Musk so I’m going to buy out-of-the-money call options expiring Friday because the stock will go up 200% today,” but the latter approach happens to work better right now.

Why does the dumb approach work better right now? Because there are a lot of people investing a lot of money without doing DCF analysis. This isn’t to say they’re wrong. It’s just to say the markets are less predictable than they were before when everyone measured companies against the same standard and made decisions using more or less the same algorithm, inputting more or less the same data to those algorithms.

Now, because of some combination of Robinhood, quarantines, low interest rates, and amazing returns from various tech stocks and crypto, people are investing based on memes. And because everyone knows people are doing this (i.e. it’s predictable) more people are piling on the bandwagon, making it even more true. For instance I have no interest or belief in Dogecoin, but I did make a couple thousand bucks on it this spring because I had a feeling about it. I am not dumb, I made a couple thousand bucks. But my actions were driven by and in turn helped drive the dynamic that is making everything dumb right now. This is the greater fool theory in action.

It’s fun to make money on risky short-term bets that could go to the moon, but it’s incredibly important to realize that there is a pretty bright line separating gambling from investing. Investing is doing your homework, coming up with an independent belief about what you think a business’s cash flows are likely to be in the future, and buying if the price of the company now is lower than the net present value of the cash flows in the future.

Part of the reason conservative “investing” types are so angry about all the “degenerate meme gambling” is it drives up prices and makes it hard for them to find good investments. For example I am pretty bullish on Tesla, but I’m less certain I want to buy the stock at today’s prices! It’s kind of annoying that a lot of people are willing to buy it at almost any price because Lord Musk is their hero and at the helm.

But then again, if there really are that many people who believe so deeply in Tesla that they’d buy at any price, maybe that’s an important signal. Maybe we don’t see the same behavior with AT&T for good reason. After all, memes control everything.

In sum, I don’t think there’s one right way to value a company. Traditionalists will tell you that DCF is the only way, but as we learned today it’s clear that DCF depends on variables that are impossible to know with any certainty. And while the long-term value of the stock is at some level based on the cash that will get returned to investors, we still have to go through the short run in order to get to the long run. And in the short run, companies with a lot of true believers and high stock prices will find it easier to undertake new projects which might give them an advantage in the long-run.

There’s no getting around it: valuation is complex. But I find it endlessly fascinating from a practical and philosophical perspective, and I hope after reading this you do, too.

...

PS—If you want me to write more in-depth explainers of fundamental concepts like this, hit the “amazing” button below.

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Hey Nathan and Eric - amazing article - keep them coming! I wanted to share some musings that your article has inspired:

"Valuation has and will become increasingly difficult to rely on because we live in an increasingly VUCA world (volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity). It is therefore necessary to change how we use valuation as a tool from a crystal ball to a compass. When we use valuation as a compass, it is less about knowing what the value is at any point in time, but rather knowing how the value is changing to generate insights which enable aligned action which ultimately will most accurately predict the future value of a company. Old valuation methods and tools are costly and slow and generate a still frame snapshot valuation that is not very useful. The new valuation methods and tools are costless, dynamic, and instantaneous and generate a movie valuation that is exponentially more valuable than an old valuation snapshot because it provides the what, how, and why of a business valuation that actually most likely will be."

What do you think?