Strategy trivia time! Here’s a fun quote from 1996. Do you know who said it?

“Content is where I expect much of the real money will be made on the Internet, just as it was in broadcasting.”

If you guessed it was a media tycoon, like Ted Turner or Rupert Murdoch, then you’d be wrong. It was actually Bill Gates! He wrote it in an essay titled “Content is King.”

I find this quote kind of amazing. Today, most of Gates’ peers (technology executives and investors) would vehemently disagree with it. I know this because I’ve experienced it personally. If I had a nickel for every VC that’s told me media is a bad business and I should really stop fooling around with content and build a proper software startup, like a civilized person, I’d be, umm, well-capitalized ;)

And, look, I get it. Technology businesses really are amazing. Bill Gates might have been wrong in 1996. But I think great media businesses are massively underrated and misunderstood in technology circles.

In my experience with Hardbound, Gimlet, Substack, and now the Everything bundle, I’ve come to believe that content can create incredibly strong moats. There are properties inherent to narratives and ideas that make them naturally powerful — kind of like how social networks, marketplaces, and platforms are inherently power-prone.

But not every media business benefits from them. There are winners and losers. To understand why — and, in the process, improve your chances of building and picking winners — we’ve got to dive into the mechanics of how these powers actually operate.

I have long searched for a book or essay that lays it all out, but couldn’t find a comprehensive guide. So this is my attempt to create one.

It’s also important to note that I’m putting my money where my mouth is — these principles inform the conversations Dan and I have every day about the work we’re doing to build the bundle. It’s far too soon to tell if it will work yet, and it’s far from the only factor that will determine our outcome, but we’re happy with our progress so far.

So, here’s the plan:

We’re going to analyze media from a systems perspective, and explore the properties that make it a good source of power. We’ll use my favorite framework, Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers, to structure our exploration. If you haven’t read 7 Powers, that’s totally fine. It’s a wonderful book and you should read it, but for our purposes all you need to know is it’s a list of the different types of powers businesses can have, which enable them to maintain profitability and resist competitive arbitrage. For each power type, I’ll explain the ways content can create it.

Ready? Great! Let’s dive in.

1. Scale Economies

Content can be infinitely copied and distributed for free. There are basically no variable costs — it’s all fixed. This creates a situation where scale economies rule the day. The bigger you get, the more you can invest in creating ever higher-quality content. And the better your content, the more cash it generates, the more you can reinvest to increase the quantity and quality of your output. It’s a positive feedback loop.

The key phenomenon to focus on here is how correlated increased investment is with increased success. It’s easy to spend more than your competitor on creating content, but it can be hard to translate that increased investment into predictable increases in value to audiences. For example, Joe Rogan’s podcast costs very little to create, and no matter how much other podcasts spend, his audience keeps on listening.

But the dynamics in audio are unique. Other mediums, like video games and movies, require massive investment, making it extremely difficult for anyone except the biggest studios to compete at the highest levels. For example, in 2019, Disney created 7 of the top 10 grossing films. There are a lot of reasons for that, but certainly one of the biggest is sheer economies of scale.

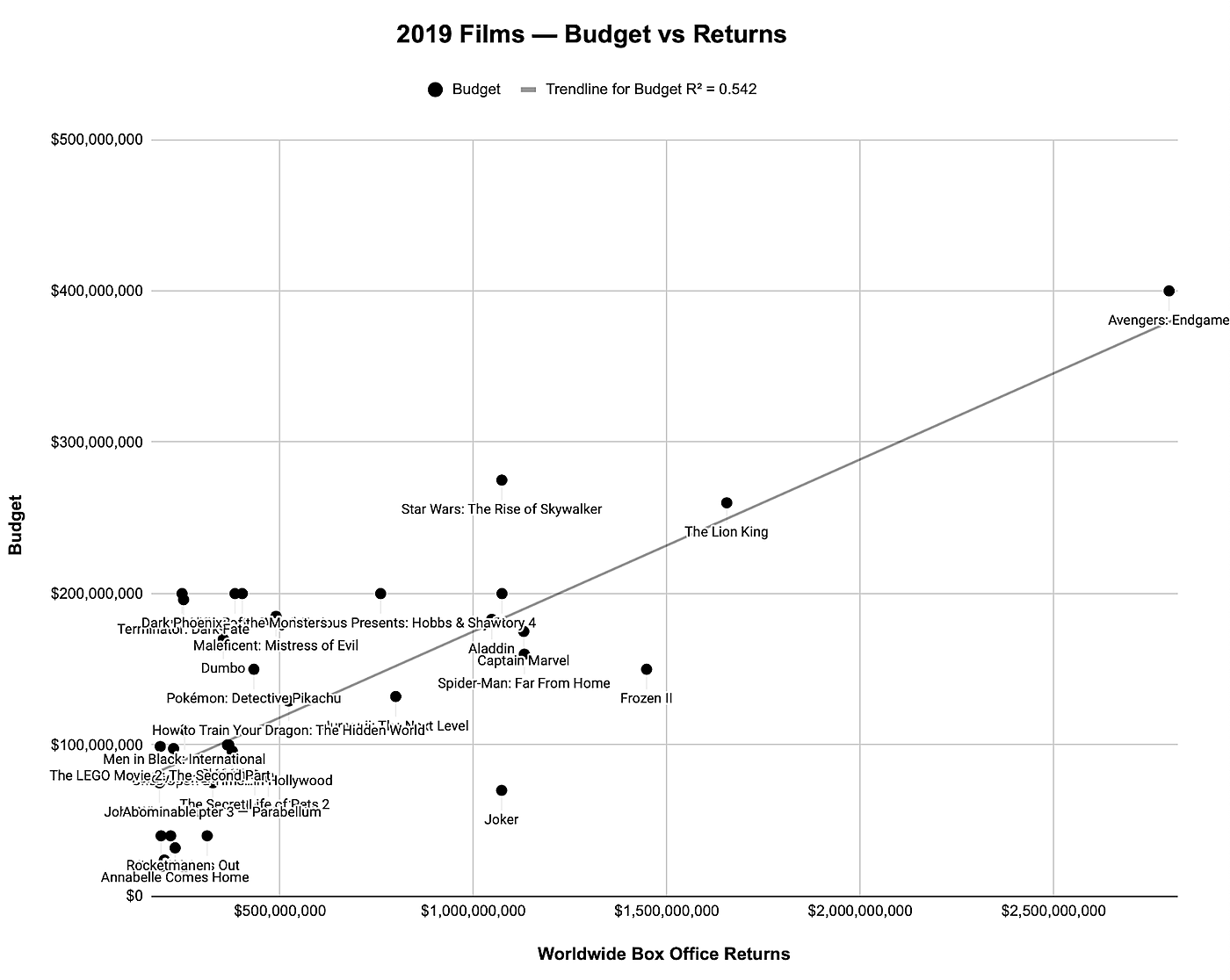

Here’s a scatter chart of the top 50 grossing films from 2019 with budget on the y-axis and worldwide box office returns on the x-axis. There’s a slight linear correlation between budget and returns, but more importantly, none of these films cost less than $20m, and the average film cost $129m to make.

This dynamic isn’t unique to film. In many forms of content, we see that the most successful organizations also tend to spend the most in absolute terms. The New York Times pays journalists to travel all over the world and gather evidence that may or may not yield an important story. TikTok stars rent mansions and invest heavily in makeup, wardrobe, personal trainers, and chefs. Newsletter writers who spend all their time researching and writing tend to outcompete those who only spend a couple hours a week. Low-budget winners like Joe Rogan and Blumhouse are the exception, not the rule.

This is the thing many tech investors I’ve spoken with don’t get about content: they think of it as more like a variable cost than it really is. They think content businesses are about churning out an enormous volume of material, so if you want to grow you have to keep hiring more content creators. But this isn’t how successful content businesses work. They don’t primarily scale by increasing quantity, they scale by increasing quality. They’re aiming for hits. And they develop creative ways to reduce that risk by spending more.

One of those ways is massive marketing campaigns. That may seem like a waste, but when it comes to potential blockbusters, it actually makes the product itself more valuable when more people are aware of it.

Which brings me to the next power, the one I find most fascinating...

2. Network Economies

Most people think network effects only apply to communication platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and Slack. But narratives can also have network effects.

Strategy trivia time! Here’s a fun quote from 1996. Do you know who said it?

“Content is where I expect much of the real money will be made on the Internet, just as it was in broadcasting.”

If you guessed it was a media tycoon, like Ted Turner or Rupert Murdoch, then you’d be wrong. It was actually Bill Gates! He wrote it in an essay titled “Content is King.”

I find this quote kind of amazing. Today, most of Gates’ peers (technology executives and investors) would vehemently disagree with it. I know this because I’ve experienced it personally. If I had a nickel for every VC that’s told me media is a bad business and I should really stop fooling around with content and build a proper software startup, like a civilized person, I’d be, umm, well-capitalized ;)

And, look, I get it. Technology businesses really are amazing. Bill Gates might have been wrong in 1996. But I think great media businesses are massively underrated and misunderstood in technology circles.

In my experience with Hardbound, Gimlet, Substack, and now the Everything bundle, I’ve come to believe that content can create incredibly strong moats. There are properties inherent to narratives and ideas that make them naturally powerful — kind of like how social networks, marketplaces, and platforms are inherently power-prone.

But not every media business benefits from them. There are winners and losers. To understand why — and, in the process, improve your chances of building and picking winners — we’ve got to dive into the mechanics of how these powers actually operate.

I have long searched for a book or essay that lays it all out, but couldn’t find a comprehensive guide. So this is my attempt to create one.

It’s also important to note that I’m putting my money where my mouth is — these principles inform the conversations Dan and I have every day about the work we’re doing to build the bundle. It’s far too soon to tell if it will work yet, and it’s far from the only factor that will determine our outcome, but we’re happy with our progress so far.

So, here’s the plan:

We’re going to analyze media from a systems perspective, and explore the properties that make it a good source of power. We’ll use my favorite framework, Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers, to structure our exploration. If you haven’t read 7 Powers, that’s totally fine. It’s a wonderful book and you should read it, but for our purposes all you need to know is it’s a list of the different types of powers businesses can have, which enable them to maintain profitability and resist competitive arbitrage. For each power type, I’ll explain the ways content can create it.

Ready? Great! Let’s dive in.

1. Scale Economies

Content can be infinitely copied and distributed for free. There are basically no variable costs — it’s all fixed. This creates a situation where scale economies rule the day. The bigger you get, the more you can invest in creating ever higher-quality content. And the better your content, the more cash it generates, the more you can reinvest to increase the quantity and quality of your output. It’s a positive feedback loop.

The key phenomenon to focus on here is how correlated increased investment is with increased success. It’s easy to spend more than your competitor on creating content, but it can be hard to translate that increased investment into predictable increases in value to audiences. For example, Joe Rogan’s podcast costs very little to create, and no matter how much other podcasts spend, his audience keeps on listening.

But the dynamics in audio are unique. Other mediums, like video games and movies, require massive investment, making it extremely difficult for anyone except the biggest studios to compete at the highest levels. For example, in 2019, Disney created 7 of the top 10 grossing films. There are a lot of reasons for that, but certainly one of the biggest is sheer economies of scale.

Here’s a scatter chart of the top 50 grossing films from 2019 with budget on the y-axis and worldwide box office returns on the x-axis. There’s a slight linear correlation between budget and returns, but more importantly, none of these films cost less than $20m, and the average film cost $129m to make.

This dynamic isn’t unique to film. In many forms of content, we see that the most successful organizations also tend to spend the most in absolute terms. The New York Times pays journalists to travel all over the world and gather evidence that may or may not yield an important story. TikTok stars rent mansions and invest heavily in makeup, wardrobe, personal trainers, and chefs. Newsletter writers who spend all their time researching and writing tend to outcompete those who only spend a couple hours a week. Low-budget winners like Joe Rogan and Blumhouse are the exception, not the rule.

This is the thing many tech investors I’ve spoken with don’t get about content: they think of it as more like a variable cost than it really is. They think content businesses are about churning out an enormous volume of material, so if you want to grow you have to keep hiring more content creators. But this isn’t how successful content businesses work. They don’t primarily scale by increasing quantity, they scale by increasing quality. They’re aiming for hits. And they develop creative ways to reduce that risk by spending more.

One of those ways is massive marketing campaigns. That may seem like a waste, but when it comes to potential blockbusters, it actually makes the product itself more valuable when more people are aware of it.

Which brings me to the next power, the one I find most fascinating...

2. Network Economies

Most people think network effects only apply to communication platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and Slack. But narratives can also have network effects.

When we watch a movie, read a book, or listen to a podcast, we never do so in isolation. We’re equipping ourselves to understand the people around us. Have you ever met someone who hasn’t read Harry Potter? They’re treated like sinners by the Wizarding World faithful! Same with Game of Thrones, Star Wars, The Avengers, and any other popular franchise.

Why should people care if anyone else has seen their favorite show? Because shared experiences are the basis of mutual understanding. Even if we’ve never talked before, I can learn something important about you when we talk about our complex feelings towards Harry and Ginny’s relationship. You can send me a reaction gif with McGonagall giving “the look” and I will know exactly what you mean.

And this force doesn’t just apply in pop culture. Having a shared set of narratives, concepts, and symbols is the basis, ultimately, for all culture — religious, national, ethnic, commercial, scientific, etc. How can you operate in biology if you’re not familiar with Darwin? How can you operate in tech if you’re not fluent in Aggregation Theory? You can’t. Even if you think the ideas are wrong, it’s important to understand them so you can understand the things the people around you are saying and doing.

Ultimately, each new unit of content is a new unit of culture. The more popular the unit becomes, the more it gets woven into the basic fabric of society, the harder it becomes to avoid knowing it.

When you think about it, languages are just networks of words; culture is just networks of narratives; and content is the thing we do to extend the network. It’s completely obvious why languages have network effects — the more people that speak a language, the more valuable it is to speak that language — so why shouldn’t content not reflect that basic dynamic?

The practical upshot is you should focus on doubling down on your wins. Once you have something that feels like it has the potential to be a narrative that many people connect with, it’s probably better to amplify and extend that than it is to muddle the waters with a bunch of other stuff. As Nathan Barry, founder of ConvertKit, once told me: you want to build a skyscraper, rather than a strip mall.

Disney understands this — just look at how they’ve prioritized worlds like Star Wars and Marvel. Love it or hate it, the “franchise” model works.

But of course, no matter how powerful a networked world may become, it’s always possible that a new generation wants something different. And in those situations, new narratives may find strength through...

3. Counter Positioning

This term is a Hamilton Helmer original, and describes situations where startups have power relative to incumbents, thanks to a superior business model that can’t be copied without damaging their existing business. For example, Vanguard counter-positioned active investors by giving customers the ability to simply index the market, and charged rock-bottom fees. This was difficult for active investors to compete with because it required them to reduce their fees, and because the entire premise of passive fund management calls into question their core value proposition.

Content can counter-position other content, too. For example, think of Barstool Sports vs ESPN, or TMZ vs People. We often see turnover in content brands that’s caused when new brands discover something important that younger audiences want, but is incompatible with the values of the incumbent brand. The incumbents can’t copy the startups’ content, or they’d make the product worse for their existing customers.

But, honestly, I think this force is relatively weak compared to the others in this essay. There are many examples of successful media brands that change with the times and continue to attract new audiences. Just look at The New York Times (169 years old), Marvel (81 years old), and The Atlantic (163 years old). And even if an individual editorial brand can’t stand the test of time, it’s common and easy for a single corporation to own a portfolio of brands and rotate them out over time as they fade.

If you’re building a new media brand, it can help to do things your establishment competitors wouldn’t be willing to countenance. It might be a bit scary, because maybe you’re starting the business in the first place in order to impress those people, but once your audience starts growing perhaps you won’t need their validation so much.

If you’re managing an incumbent media brand, it can be useful to incrementally stretch towards new, younger audiences as much as you feel you can stomach. Of course you don’t want to lose touch with your core. But it’s important to reconsider each year what editorial guidelines are helping you, and which are harming.

But even if you fail to evolve, you might be able to retain a good portion of your existing audience, because media properties can actually have quite powerful...

4. Switching Costs

Businesses with high switching costs tend to be highly profitable, because it’s so painful for their customers to leave that they’re willing to stay and pay a premium, even if an attractive new option comes along. Typically high switching costs are caused by products that are highly complex, and deeply integrated into their customers’ operations. Salesforce, for example, has fantastically high switching costs. Once you’re in, you’re really in.

This happens in a weird way with content, too. Imagine a teenager who spends dozens of hours a week creating and consuming content about BTS, or an academic who spends years mastering a specific subfield within economics, or a die-hard 4th generation Yankees fan. These people are all literally invested. Imagine how much work they’d have to do to get the same kind of satisfaction from another subject! All their built up knowledge can be leveraged to make future content more meaningful and interesting to them. Without that history, new subjects just aren’t as compelling.

This explains why, once I fell into the Vlog Squad rabbit hole on YouTube, I chose to spend more time listening to their podcasts and watching their TikToks than seeking out new creators. I already have a ton of context, which makes even little things interesting. I don’t feel like I have time to get into some other world, unless there’s a compelling reason to do so.

This whole phenomena is connected to the more general pattern where people tend to have stable interests once they reach adulthood. Sure, they’ll dabble in new things and even pick up entirely new interests. But this is rare, and usually happens when an existing interest forms an easy bridge into a new one.

And the switching costs get even higher when communities form. For example, maybe I originally got interested in startups because I wanted to build one, but now I know so many people and I have so much of my own relationships and reputation based on it that I can’t imagine leaving.

But loyalty isn’t purely enforced by the costs of switching. With media, people also stick around because they get so much value from...

5. Branding

Brands are the sum of the perceptions people have about products and companies. They can be a source of power in two main situations:

- When quality is uncertain, and

- When people want to associate with the brand in order to signal something about themselves

For example, chain restaurants have power because of the former, and luxury brands have power rooted in the latter. Content brands have both in spades.

Let’s look at uncertainty first. This is especially important in media, because content is, for the most part, consumable. This creates a problem that we all must solve for ourselves each day: finding new good things. This is why branding is so important in content. Most content out there is junk and not right for us. But some of it is amazing. Brands are the only way we can reliably navigate to the good stuff.

The second source of branding power, social signaling, is also extremely common in content. It’s a lot easier to imbue specific meaning into media than into other types of goods like cars, diamonds, and furniture. What content lacks in its ability to signal wealth, it makes up for in its ability to signal extremely specific attributes and affinities. For example, I couldn’t tell you the difference between fans of Cowboy Bebop and Dragonball Z, but I’d wager a lot of money that millions of anime fans could go on for hours about the subtle differences in who likes one or the other.

This signaling attribute also helps explain why content has network effects. We tell people about stuff we like in order to communicate something about ourselves, but it only works if other people know what the signal means. On the other side, one of the main ways people decide what content to consume is by listening to recommendations from people they respect. So it forms a self-reinforcing cycle that makes some content wildly popular, and keeps other content from spreading. For example, I probably enjoy Scuttleblurb a bit more than Stratechery, but I mention Stratechery way more, because there’s a much greater chance that people will know what I’m talking about.

So yeah, branding matters a lot with content. But there’s an interesting difference between content branding and other forms of brands: content is much more closely tied to its creator. Which leads us to our next power...

6. Cornered Resource

This power happens when, for some reason, a business has an exclusive claim to a scarce and valuable resource. For instance, Lipitor generated nearly $100 billion for Pfizer between 1992–2001, because for most of that time Pfizer owned the exclusive patent on the drug.

With content, the ultimate cornered resource is creative talent. Creators can’t be separated from their creations. Taylor Swift has an irrevocable monopoly on Taylor Swift, no matter what derivative rights some suits may try to buy and sell. Her fans are ultimately loyal to her.

This strong bond between content and creator is a weakness for many media businesses, forcing them to pass big chunks of their profits along to talent, rather than keeping it to themselves like most businesses. This phenomenon is actually why the word “talent” exists — to distinguish absurdly expensive non-commodity employees from relatively commoditized workers.

You could look at this and say it’s a weakness of media companies, and you’d be right, but I look at it and say it’s an example of just how much power emanates from content. It’s like fire — useful, but it can burn you.

Some media companies manage this problem by devising systems that generate content without relying too much on any particular creator. Morning Brew, theSkimm, and SNL all have formats that work even if one creator leaves. The goal is to build a locus of value that lives inside the system, rather than specific individual’s brains.

Other companies exploit this strong linkage by empowering creators to go independent. Substack, where I used to work, is perhaps the most notable example. This year we’ve seen dozens of prominent journalists break away from their publications in order to go independent on Substack. The reason it’s possible is because their fans care about their creativity more than the company they used to work for.

There’s something magic that’s hard to replicate about their process that gives them power, which ties nicely into our final section...

7. Process Power

Companies that master a complex, opaque process to create superior value are said to have “process power.” The key here is that the process be extremely difficult to copy, and yet be critical to creating the benefits customers most value. The poster child for process power is Toyota. They successfully competed with US automakers by making a thousand tiny improvements to the process of car creation. When layered together, it made a huge difference. But it was so complex it took a long time for competitors to copy it.

The same force helps explain the dominance of top content creators. The creative process is also incredibly complex and opaque. Every successful creator has to cultivate their own information ecosystem, prototyping process, and methods for polishing their work. This takes years to learn, and every individual and team has to, to some extent, figure it out on their own.

Take the movie industry for example. Even if I gave you $100m, the chances are vanishingly low that you’d be able to produce a hit without enlisting the help of someone who knows the process. It takes a huge amount of complex knowledge to organize this kind of work. The same goes for any other creative endeavor — songwriting, book publishing, game design, etc.

This is pretty much the textbook definition of process power.

Conclusion

If you want to understand why some media businesses are so much bigger and more profitable than others, look no further than the powers we outlined above. You can use each of the seven to analyze any company, and you’ll probably have a pretty good understanding of what makes it work — or not.

If you want to create successful content, unfortunately I don’t think this essay will help you much. But if you do manage to create content that people love it can help you understand what power you do have, so you can manage it more effectively. For example it may empower star writers to go independent, extend their hits, invest in marketing so they reap the advantages of network effects, etc.

Mostly, I’m curious to hear what you think. Did I get it right? Do you have counter-examples? I’d love to hear from you. That’s the only way to make these theories better.

An earlier version of this story incorrectly claimed that Bill Gates originated the phrase “content is king” in his 1994 essay. It was actually Sumner Redstone! Thanks to Mike Raab for catching this.

Ideas and Apps to

Thrive in the AI Age

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Ideas and Apps to

Thrive in the AI Age

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

"For example, I couldn’t tell you the difference between fans of Cowboy Bebop and Dragonball Z, but I’d wager a lot of money that millions of anime fans could go on for hours about the subtle differences in who likes one or the other."

What? That's ridiculous. Let me give you an example of how ridiculous it is, replace Cowboy Bebop and Dragonball Z with something you're more familiar with and keep the rest of the sentence the same:

For example, I couldn’t tell you the difference between fans of Harry Potter and Game of Thrones, but I’d wager a lot of money that millions of fantasy fans could go on for hours about the subtle differences in who likes one or the other.

@GBM Right, that is the point I'm making! Before that, I say "What content lacks in its ability to signal wealth, it makes up for in its ability to signal extremely specific attributes and affinities."

To you these seem like wildly different properties (because they are!) but to me from a distance I just squint and see "anime". It's great that the more into something you get, the more the specifics matter, because that creates room for all sorts of stuff to exist that wouldn't if we didn't care about the fine details that distinguish one media property from another.

Really well-articulated article which is still so relevant over a year later. I haven't seen any analysis about "content is king" that deeply and widely before so thank you so much for amazing perspectives about content and 7 powers in general which I think can be used to analysis almost anything.

"The poster child for process power is Toyota. They successfully competed with US automakers by making a thousand tiny improvements to the process of car creation. When layered together, it made a huge difference. But it was so complex it took a long time for competitors to copy it."

Execution is exponential. Mr. Beast too.

it's amazing