We’re in the midst of the biggest paradigm shift in technology since the internet and the personal computer. If you want to understand what’s going to happen with AI, you have to understand how previous technology shifts played out—because history repeats itself. That’s why we’re publishing this original essay by digital strategist and historian Gareth Edwards on the secret history of the first PC revolution. It's a long read with which to settle into the weekend. We hope it sheds light on the past—and on the future. We’d like to publish more of these pieces by Gareth, so if you like it, please let us know. —Dan

In September 1974, Ed Roberts was sitting at the bank in a foreclosure meeting. His once-profitable calculator company, Micro Instrument and Telemetry Systems (MITS), had exhausted its $250,000 overdraft and was on the verge of bankruptcy. But Roberts wasn’t getting ready to shut down. Instead, he was soliciting a $65,000 loan. Not to spend on calculators, he explained to the bank, but for something completely different. Something nobody had done before. He planned to build an affordable personal computer.

The bankers were dubious. Everyone knew that computers were large and expensive, the domain of big business. “The banker asked me, ‘Well, how many of these do you think you'll sell?'” Roberts remembered later.

It was a question that he’d hoped they wouldn’t ask because Roberts had no answer. He had decided to pivot his entire company on a personal hunch: that he could sell a large number of low-cost computers in a market where most companies expected to sell four or five expensive ones every year. “I said, ‘I think we'll sell seven or 800 of them over the next year.’ [The banker] laughed at me, accused me of being a wide-eyed optimist and all that."

For a second, Roberts thought that this was the end of MITS. Instead, the banker sighed and signed off on the loan. He explained that he saw little value in foreclosing now. If, somehow, Roberts managed to sell even 200 of these machines, it would yield the bank some return.

Roberts went away surprised, but happy. This didn’t mean he wasn’t worried. His business depended on him being right about two things everyone insisted were wrong: that you could create a useful computer for less than $400, and that there were people who would buy it.

But Roberts had conviction. "Here’s the thing that’s so hard for people to understand now,” he said. “Those of us who wanted computers lusted after computers. That's the only way to describe it. The idea of possessing your own computer... I mean... wow. There were only one or two things more exciting about that. And I'm not even sure about them!"

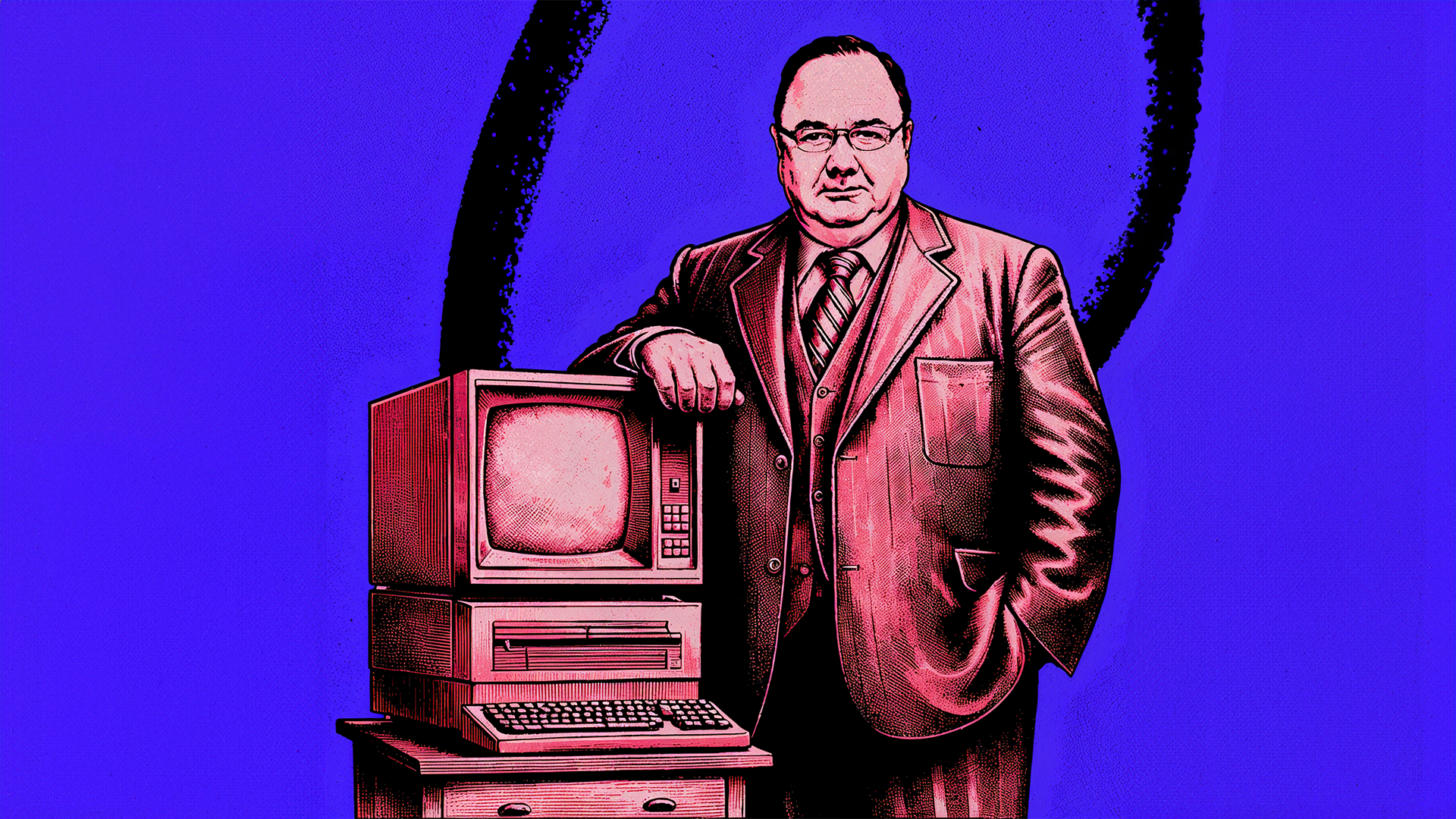

We often picture tech disruptors as brash, dynamic figures who are keen to be both seen and heard. Yet the personal computing industry was largely sparked by a straight-talking ex-Air Force officer—one more Ron Swanson than Elon Musk. He ignored claims by IBM and others that people didn’t want a computer at home, and risked his whole company on a hunch that they were wrong. His approach to business was different from the “move fast and break things” model we’ve come to expect from tech entrepreneurs, yet he succeeded beyond all expectations because of it.

This is the story of Ed Roberts, the man who created the personal computer, launched the careers of Bill Gates and Steve Wozniak, and decided—at the height of his success—to walk away. It is based on archival video interviews with Roberts, Gates, Steve Wozniak, and many of the other key figures involved. I also draw on written accounts by Forrest Mims, Paul Allen, and others who were there; contemporary publications, such as Dr. Dobbs Journal and Popular Electronics; and books like Fire in the Valley and Endless Loop: A History of Basic.

Dreams of selling a computer

Roberts had started to act on his hunch about personal computers long before meeting with the bank. As early as 1972, as the power of microprocessor chips was increasing and their prices were dropping, he sensed that there was an opportunity to produce a mass-market computer. He also understood that the electronic calculator market in which MITS had enjoyed great success was about to implode.

Like most of the firms that had ridden the calculator boom, MITS made very few parts itself. The company designed the boards, selected the chips, sourced the parts, and (for an additional fee) would even assemble your calculator for you. However, as demand grew, chip manufacturers started entering the market, and companies like Texas Instruments began to sell directly to customers. They could offer cheaper products than third-party assemblers like MITS. Almost overnight, Roberts’s profit margins disappeared.

Roberts wanted to exit the calculator market entirely—and he had experience making bold decisions. Initially, MITS made electronic telemetry systems for model rockets—hence, its full name, Micro Instrument and Telemetry System, which was cleverly selected to create a mental association with MIT, the university. After several years catering to rocket enthusiasts, Roberts had sensed that the market for electronic calculators was about to explode. When his founding partners in MITS proved reluctant to pivot, Roberts offered to buy them out. After they accepted, he took the company successfully into the calculator market. As far as he was concerned, pivoting to affordable computers was a natural progression from pivoting to affordable calculators.

"I know now that I'm onto something good when everyone else thinks it’s a bad idea,” he said. “I just didn't figure that out until later."

Roberts’s interest in computers was different from most of the customers who would eventually buy his machine. He was a realist—fascinated by what they could do now, rather than the future they represented. In fact, he had always wanted to become a doctor, but he grew up in a relatively low-income family, so he had to find a way to pay for college. He chose to study electrical engineering and committed to a period of service afterward with the U.S. Air Force (USAAF), which ensured that his tuition would be covered. After graduation, he joined the USAAF Weapons Lab at Kirkland Air Force Base near Albuquerque. Some years later, he created MITs along with other Air Force personnel.

At college and Kirkland, Roberts had encountered some of the most powerful computers then available. He was fascinated by computers—how they could democratize power, and who they could offer that power to.

“To some extent, your worth has always been measured by the number of people you control—the number of people you ‘own,’ so to speak,” Roberts explained. “In the case of the computer, one person can do the work of thousands. So by any historical definition, if you have a computer, you’re wealthy. I mean, wealthy beyond all imagination. That’s always intrigued me about computers. The enormous amount of power it gives us regular folks.”

Negotiating an affordable chip

In his quest to pivot MITS to computers, Roberts found an ally in Bill Yates, an Air Force veteran who’d worked alongside Roberts at Kirkland. Yates was a talented electrical engineer. When Roberts had needed to buy out his MITS co-founders, Yates stepped in to help. He partially funded the purchase in return for a share of the company.

Roberts and Yates watched as the microprocessor market developed. At the time, the processing power of most available chips was low, which limited their potential usefulness for real-world applications. The National Semiconductor IMP-8 and IMP-16 microprocessors required extra hardware to run, rendering them unusable on a cost basis. Another possibility was the Intel 4004 or 8008 chips. However, the duo soon realized that they weren’t powerful enough to create a fully programmable machine. There were rumors that Motorola was working on a solid microprocessor, but that’s all they were—rumors.

By the beginning of 1974, both men knew the window to save MITS was shrinking. The company was in the red and was down to fewer than 20 employees. It was then that they enjoyed a moment of luck.

Roberts had cultivated a strong relationship with Intel, from which he regularly sourced calculator chips. He mentioned to MITS’s Intel rep that they were hunting for a microprocessor with which to build a home computer. The rep took Roberts and Yates into his confidence and confessed that Intel had an unannounced microprocessor that was almost ready—the Intel 8080, which was a major improvement on the 8008. He suggested that it might be powerful enough to meet their needs. He also secured them early access to the 8080’s data schematics, as well as some samples. Roberts and Yates immediately recognized that the 8080 was exactly what they had been searching for.

Roberts’s straight-talking approach with his suppliers and financial backers occasionally created problems for MITS in the cut-throat calculator market, where overpromising and under-delivering were routine. But it also resulted in a level of trust with MITS’s partners that few other companies enjoyed. This had already landed the company early access to Intel’s new chip. Now it proved its worth financially as well. Intel planned to sell the 8080 microprocessor for $360 a unit. It cost the company barely a fifth of that to manufacture them, but it correctly believed that the majority of its customers—computer firms manufacturing machines that cost tens of thousands of dollars—would pay the high price.

Roberts, however, was a veteran of the brutal price wars over calculator chips. He knew that Intel’s sales team liked the security that bulk orders offered them, so he took a gamble. He told Intel that MITS was prepared to order 8080 microprocessors in batches of 1,000, at a minimum. In return, he wanted a massive discount. Intel agreed to a much lower price of $70.

This deal was a game changer. It made MITS’s plans to sell a personal computer that retailed below $400 viable—an impossibility if $360 of that budget went to the microprocessor. Armed with the new deal, Yates began designing circuit boards for a computer based on the 8080, while Roberts created the logic interface—or series of instructions—that would allow their new microprocessor to work with up to 256 bytes of memory and a 2MHZ clock. (This may not seem like much now, but it would make the machine almost as powerful as the computer that had landed Apollo 11’s astronauts on the moon a decade earlier.) It was enough that a home user with enough time and creativity could program the machine to do genuinely useful things.

During the design process, Roberts realized that customers might come up with ways to use the new computer that he hadn’t considered. In what would prove to be a revolutionary decision, he built sockets that would allow peripheral cards to expand the machine’s capabilities. In doing so, he created the open architecture philosophy on top of which much of the computer industry innovated.

Media coverage wars ensue

By June 1974, with the last of its cash reserves almost exhausted, MITS was close to having a workable computer. But the company had not yet worked out how to let its potential buyers know it existed.

One day in July, Roberts got a phone call. “Ed! It’s Les Solomon,” came a cheerful voice. “You’ve still got that 8080 project going on, right?”

“We do.”

“Great. Then I’m coming to Albuquerque.”

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

.50.43_AM.png)

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Very nice piece of writing. I knew the Altair started it all yet I knew very little of this story. Thanks!

This was great! Lots of great detail presented in a breezy way. More like this, please!

It was written beautifully , thank you for taking the time to share this hidden history peace with us .Yahli

Wonderful! I was in Albuquerque decades later, and recall a local foreign car father and son shop, who recalled some of these people, and their drive and dreams.

And the old huge computers and horrible stacks of punched cards. Cold cold cold chilled non ilitary computers… starting to get me and other students to “ think” computer in business settings.

Thanks.

Always great reading about the history of the industry. Really great article!!

As someone in tech, this was just an amazing piece to read and rather makes me ashamed that I did not know it myself.

My wife and most of her family are Cochran, Georgia natives. Ed was my wife's mother's doctor. Ed was a great doctor, extremely caring, and modest about his technical achievements. Hardly anyone in his small town knew of his significance in computer history. Early personal computers, such as the Altair, inspired me to later become a computer scientist.

Amazing writeup! Really takes you along.

Over the last couple of days I read all The Crazy Ones stories. So well written - thank you Gareth!

great piece!

Wonderful and inspiring story. Thanks for this delight

Just fascinating stuff! Like others I knew how important was the Altair 8800 but nothing of the man behind it. More like this please!