Sponsor Superorganizers!

Superorganizers is now accepting select sponsors. We’re looking for companies who want to bring new tools, systems, and technology to our audience of 25,000+ early adopters in tech.

Interested?

Most people believe that they’re not doing creative work because they don’t have enough time. But that’s like saying you need a hammer to build a house. Sure, a hammer is a useful thing when building houses. Time is useful when doing creative work. But both are tools. You could build a house without hammers if you had to, and there are many kinds of things that could become hammers if you don’t have an actual hammer handy.

The same is true for time. Time is a useful and necessary tool for creative work. But if you know what the tool is doing for you, you can decide when you might need it and what other things might work to give you what you want if time is in short supply.

The most important thing to realize is that, when it comes to creative work, not all time is created equal. If you pay attention you’ll notice that there are short expanses of time where you can get a lot done and long expanses of time where you get almost nothing done.

My friend Sam Koppelman wrote a bestselling book, Impeach, in about two weeks. Elton John and Bernie Taupin wrote Your Song in 20 minutes.

In an ideal world you could blurt out a best-selling book between meetings, or compose a hit song while waiting at daycare pickup. Theoretically, you have just as much time as Elton John did.

Why does that feel so hard?

In creative work there are two phases: exploration and execution. In the exploration phase, you don’t know what the thing is going to be, you don’t have all of the information or ideas you want to have, you don’t even know if what you’re thinking about is important, and any little breeze in the wrong direction might blow you off course. In the execution phase, you are inspired, you know what the thing is, you know how to make it, it feels urgent; all you need to do is sit down and do the thing.

Execution is Elton John writing Your Song in 20 minutes. Exploration is everything that happened before that.

In reality, you go back and forth between these phases often during a project—especially for a big project. But the really interesting thing is that the relationship between time and work output is different for each.

In the execution phase there is a linear relationship between time and work output. The more time you put in, generally, the more work you’ll be able to get done. In the execution phase it’s also easier to put in the time. You’re inspired: time feels like it’s going by more quickly, and the work takes less effort. Outside work and personal influences fall away, and it can even be easier to sneak time in on a project in between other tasks you might have to do. Your whole being is focused on the thing even when you’re not actually in front of your desk, and you’re raring to let ‘er rip, baby.

In the exploration phase, everything is different. There’s a non-linear relationship between time and work output. You’re not really sure what you’re making or whether it will be good. It’s harder to see the thing in your mind. You’re much more susceptible to outside influences—other people, projects, and events that might suck your attention away from the thing you’re trying to do.

If all you had to do was the execution phase of creative work, you’d be able to do it between meetings no problem. But the truly hard, terrible, nasty truth is that you need to do the exploration phase in order to get to the execution phase. So when we talk about not having enough time to do creative work, what we actually mean is that we don’t have enough time to do the exploration phase of creative work.

So why is exploration so hard?

The Neuroscience of Value

Every goal you have gets assigned a value by your brain. It’s done by a piece of the brain called the orbitofrontal cortex or OFC. Your OFC figures out what kinds of rewards you’re likely to get by achieving a goal. It’s also highly connected to the amygdala (the fear circuit in your brain) which means it’s responsible for figuring out how terrible the consequences will be if you don’t do something. Based on the expected rewards and punishments your OFC calculates, your brain then decides at any given moment which goal is most valuable to pursue. (For more on this click here.)

This helps us understand the difference between the execution and exploration phases of creative work:

The reason it’s easy to do creative work in the execution phase is because you’ve reduced the uncertainty about the work enough that your brain calculates a lot of rewards for pursuing that goal—and also, possibly a lot of negative outcomes for not doing it.

The reason it’s hard to do creative work in the exploration phase is that it’s so uncertain that there aren’t many perceived rewards for accomplishing the goal, there’s little punishment in not accomplishing it, and there is a higher perceived value to pursuing other unrelated activities.

This gives us a roadmap to doing more creative work. What we need to do is, in the exploration phase, raise the perceived value of doing the work, raise the perceived costs of not doing the work, and lower the perceived value of doing other things.

There are lots of ways to do this. Here are a few ideas.

Make Doing the Work More Rewarding

Connecting into why it’s valuable. Sometimes you get so lost in a project that you forget why you started it in the first place, or why doing this kind of work is important to you at all. If you reconnect to that, you’ll raise the perceived value of doing the work in your brain—and it will make it easier to stick with. Try writing about why the work is important, or spend some time reflecting on times in the past where you’ve felt most connected to it. If that doesn’t work try talking to a supportive friend about the work and have them reflect back to you what they think is interesting about it, or what pieces of it are exciting to them.

Get communal support. If two or more people do an activity together, it raises the perceived value of that activity (and the costs of not doing it.) So if you can create routines with friends or co-workers to do creative work together at certain times, you’ll be more likely to actually do it.

Reframe non-productive time. One of the reasons the exploration phase of the work is low value is that most of it doesn’t look like work. It’s lots of reading, and sitting and thinking, and doodling, and trying things that lead to dead ends. Non-productive time feels like a waste—but it doesn’t have to! One way to think about this kind of time is that it is productive, it just doesn’t look like it. The exploration phase is the seed of your project growing roots underground, before it sprouts through the surface. Another way to think about this time is to reframe it as play. Forget about productivity, and just allow yourself to enjoy time to mess around and have fun.

Consume things that inspire you. Seeing other people do things that inspire you will raise the perceived value of the work in your mind. It’ll feel more visceral, the rewards more tangible, and it’ll make you feel like you’re leaning forward into the exploration that you’re in. It might also help you narrow into what you’re really trying to do which will reduce uncertainty, and raise perceived value.

Reframe the work as an escape. Everyone needs a safe place to escape sometimes from the hard or scary things going on around them. If your creative work can act as a temporary escape and source of relaxation, it will raise its perceived value in your mind. It will be easier to justify putting off other problems to take the time you need to recover (and also get your work done.)

Make Not Doing the Work More Scary

Deadlines. You can raise the perceived cost of not doing the work by setting a deadline. This will work to increase the goal’s value in your mind, especially as the deadline approaches. Your urgency for accomplishing the goal will rise, too.

Public commitments. You can increase the effectiveness of a deadline by making a public commitment to achieve it. Everyone has a strong desire to avoid looking bad in front of other people, and you can use that to increase the perceived value of accomplishing your goal.

Negative visualization. Another good way to make not doing the work more scary is to spend some time thinking about what the consequences might be if you don’t do your creative work. See if you can get your heart pumping a little bit. As I wrote about in ‘Will Worrying Make You Better?’ this is a tool to be wielded carefully—but it can be an effective one.

Make Doing Other Things Less Rewarding

Reduce or eliminate distractions. Other goals aren’t going to be as rewarding if they’re not top of mind. Block out outside information, services, and people that might affect the reward calculation your brain is conducting on the work at hand.

Do it right when you wake up. This goes along with reducing or eliminating distractions. When you wake up your brain is reset, and there won’t usually be as many other pressing sources of reward present. If you can reserve time in the morning to do your creative work you may have an easier time staying focused. (Note: this won’t work for everyone, especially if you’re not a morning person.)

Take the long view. Another way to reduce the reward value assigned to other tasks is to attend to how important they will actually be in 10 years. Many things that feel like emergencies today are, in fact, going to be irrelevant to you as time goes on. If you can take the long view on your outside tasks, you might have an easier time attending to your creative work.

Affect Dysregulation and Creative Work

Even if you’re doing all of the above, you might sit down at your computer or easel and try to get something out—and it still just feels blah. This is important to pay attention to.

If there are lots of other goals and tasks with high value swimming around in your mind and body it’s going to be hard to do creative work—not just because of focus, but because of feeling.

When you write or make art it’s supremely important to be able to know how what you’re working on makes you feel. That little thing in your heart is the dowsing rod that vibrates on the same frequency as the reader’s heart. If it moves, your reader’s heart will move too. It guides the way.

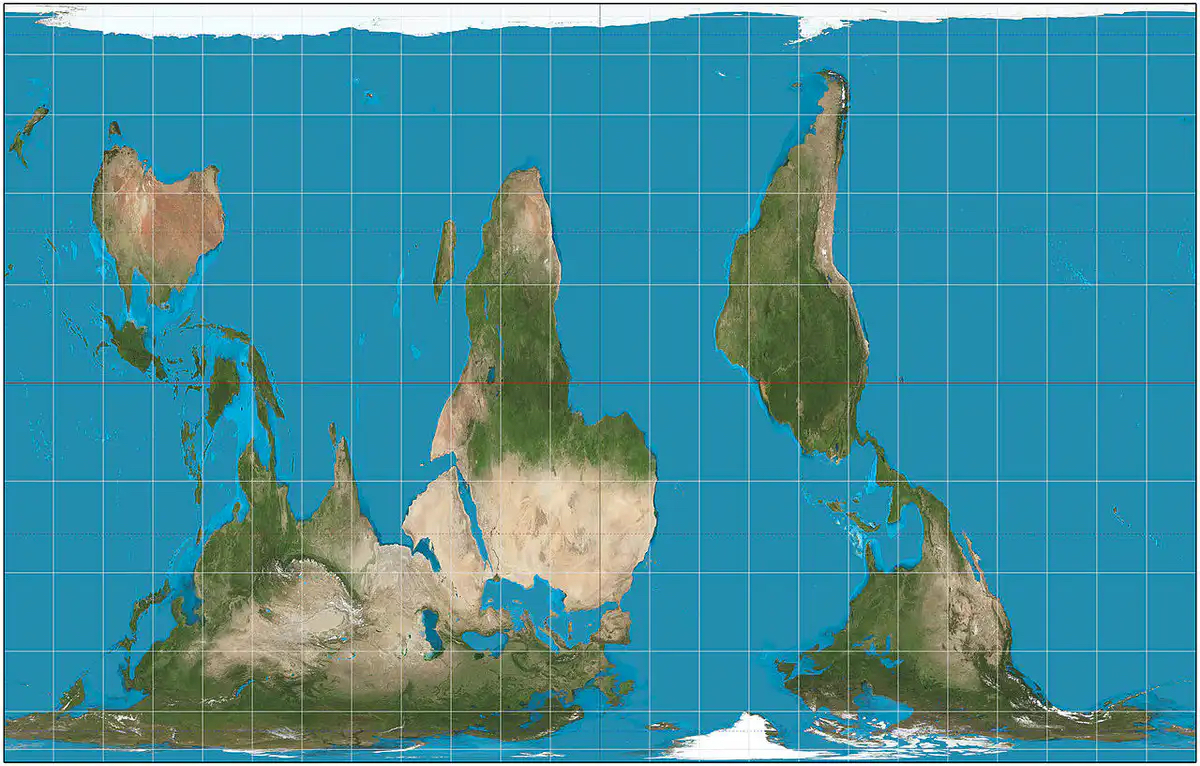

But when there are lots of other high-value things going on, your dowsing rod breaks. You look at what you’re making and it all looks terrible. Boring. Off-topic. Embarrassing. That’s not an objective property of the work, it’s about the relationship between the work and your emotional state. It’s like looking at a map of the world upside down. The pixels are all the same but the way they strike you is totally different:

The fixes I suggested above can be helpful to reset your state and allow you to look at your map right-side up. But, possibly the best fix is to use your dysregulation as an opportunity to create something that does align with your emotional state.Is geopolitics making it hard to focus on your SaaS analysis? Maybe put that analysis to the side and write about something that does feel aligned.

This is easy for me as a productivity writer: any emotional state is something important to explore, and a potential opportunity for a piece. But the same is true for any kind of work—you just have to be open to discovering it

If you can find ways to ride the lightning of your emotions you’ll be able to produce creative work in a much wider variety of affective states, and maybe, with less time.

Did you like this essay and want to go deeper?

Check out more of my essays on the psychology of productivity below.

- Beware of Pet Explanations how jumping to conclusions leads us to keep doing the same dumb things over and over, and how we can expand our psychological flexibility to find things that work.

- What is Underneath Productivity? Productivity is actually about psychology, neuroscience, philosophy, and literature. If we're honest about that we might get more done—and live better lives.

- How Hard Should I Push Myself? How you can use—and misuse—the stress response to get more done.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

I love how Ryan Singer explains how to show progress in Shape Up chapter 13. "Every piece of work has two phases. First there’s the uphill phase of figuring out what our approach is and what we’re going to do. Then, once we can see all the work involved, there’s the downhill phase of execution." That seems similar to the exploration and execution phases you describe.

@anton yes absolutely! hadn't seen that, but it's exactly right!

Have you ever read Lateral Thinking by Edward DeBono? Probably the best creative book I read as I realized in my 30 plus years of entrepreneural ventures and investing my best ideas came from observing something in one area and then realizing it could be used just as well in others..worth the read....

@cg I haven't yet! but putting it on my list!